Boxer-Twin Believer

CW PROFILE

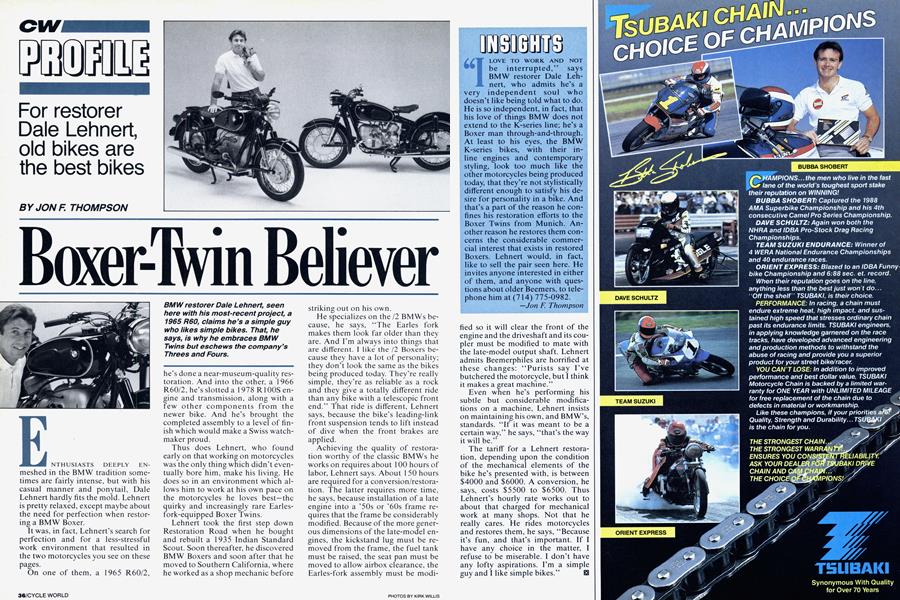

For restorer Dale Lehnert, old bikes are the best bikes

JON F. THOMPSON

ENTHUSIASTS DEEPLY ENmeshed in the BMW tradition sometimes are fairly intense, but with his casual manner and ponytail, Dale Lehnert hardly fits the mold. Lehnert is pretty relaxed, except maybe about the need for perfection when restoring a BMW Boxer.

It was, in fact, Lehnert’s search for perfection and for a less-stressful work environment that resulted in the two motorcycles you see on these pages.

On one of them, a 1965 R60/2, he’s done a near-museum-quality restoration. And into the other, a 1966 R60/2, he’s slotted a 1978 R100S engine and transmission, along with a few other components from the newer bike. And he’s brought the completed assembly to a level of finish which would make a Swiss watchmaker proud.

Thus does Lehnert, who found early on that working on motorcycles was the only thing which didn’t eventually bore him, make his living. He does so in an environment which allows him to work at his own pace on the motorcycles he loves best—the quirky and increasingly rare Earlesfork-equipped Boxer Twins.

Lehnert took the first step down Restoration Road when he bought and rebuilt a 1935 Indian Standard Scout. Soon thereafter, he discovered BMW Boxers and soon after that he moved to Southern California, where he worked as a shop mechanic before striking out on his own.

He specializes on the /2 BMWs because, he says, “The Earles fork makes them look far older than they are. And I’m always into things that are different. I like the /2 Boxers because they have a lot of personality; they don’t look the same as the bikes being produced today. They’re really simple, they’re as reliable as a rock and they give a totally different ride than any bike with a telescopic front end.’’ That ride is different, Lehnert says, because the bike’s leading-link front suspension tends to lift instead of dive when the front brakes are applied.

Achieving the quality of restoration worthy of the classic BMWs he works on requires about 100 hours of labor, Lehnert says. About 150 hours are required for a conversion/restoration. The latter requires more time, he says, because installation of a late engine into a ’50s or ’60s frame requires that the frame be considerably modified. Because of the more generous dimensions of the late-model engines, the kickstand lug must be removed from the frame, the fuel tank must be raised, the seat pan must be moved to allow airbox clearance, the Earles-fork assembly must be modified so it will clear the front of the engine and the driveshaft and its coupler must be modified to mate with the late-model output shaft. Lehnert admits Beemerphiles are horrified at these changes: “Purists say I’ve butchered the motorcycle, but I think it makes a great machine.”

Even when he’s performing his subtle but considerable modifications on a machine, Lehnert insists on maintaining his own, and BMW’s, standards. “If it was meant to be a certain way,” he says, “that’s the way it will be.”

The tariff for a Lehnert restoration, depending upon the condition of the mechanical elements of the bike he’s presented with, is between $4000 and $6000. A conversion, he says, costs $5500 to $6500. Thus Lehnert’s hourly rate works out to about that charged for mechanical work at many shops. Not that he really cares. He rides motorcycles and restores them, he says, “Because it’s fun, and that’s important. If I have any choice in the matter, I refuse to be miserable. I don’t have any lofty aspirations. I’m a simple guy and I like simple bikes.” S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

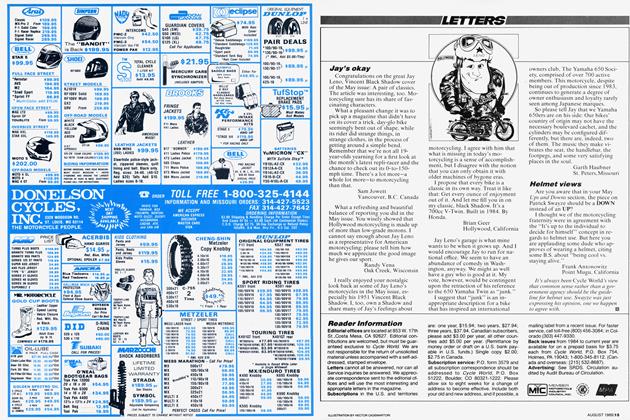

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards