LEANINGS

Crossroads

Peter Egan

WHEN ELVIS WAS BACK IN HIS WILD, pre-Army days, an interviewer once asked the secret of his unusual looseness and rhythm on stage. Elvis is reported to have said, “Well, sir, without muh left leg ah'd be dead.”

Watching old films now, you can see what he meant. That left knee just naturally wanted to move and swivel, and it became a kind of personal signature. As bluesman John Lee Hooker would say, the poor boy had it in him and it had to come out.

Elvis's famous phrase came back to haunt me about six months ago, though not in the same cheerful context.

I found myself in the office of an orthopedic specialist, sitting on the edge of one of those tissue-covered examination tables with my legs dangling down. One foot formed a general right angle with my leg and the other one just kind of hung there, toes pointing toward the floor. For about 20 minutes the doctor had been poking me with pins, tapping with rubber hammers and trying to get me to move ankle muscles that wouldn’t move.

“I would say,” he told me at last, “that you have severely damaged the sciatic nerve where it runs through the joint in your right knee. You've either pinched it or done something to cut off the circulation for a long period of time. Tell me again what you did this weekend.”

“I spent all Sunday afternoon crouched next to my Triumph 650, working on the engine in my garage. When I stood up to come into the house for dinner, my leg was numb from the knee down. When I got up this morning, the numbness was still there and my ankle didn't work at all. It still feels like my foot's asleep.”

“Sounds like these Triumph motorcycles are a hazard to your health,” the doctor said, smiling. I grinned crookedly, in my best imitation of Indiana Jones gazing into a temple full of snakes.

The doctor sat at his desk and began to write. “We have to get you fitted for a foot brace. It'll be one of those molded plastic braces that fit inside your shoe. We’ve got to rest those damaged nerves to see if they’ll regenerate. So stay off the motorcycles, and I'd avoid driving cars as much as possible. Also, stay off your feet at work. What do you do for a living, by the way?”

“I ride motorcycles and drive cars and write about them.”

The doctor winced. “Any hobbies, other than cars and motorcycles?”

“I have an old Piper Cub that I

fly"

“I d avoid flying, too. You don't need the vibration, or the pressure on your ankle, from the pedals.”

“Is this going to get better, Doc?” He frowned. “Hard to say. You might make a complete recovery, but I’ve seen cases where a damaged nerve just doesn’t come back. You might need the foot brace permanently. It'll take some time before we know. Nerves heal slowly.”

I scuffed out of the place, dragging my foot across the parking lot, and climbed into my Chevy van, which I had chosen that morning because it had an automatic transmission. I lifted my right knee with both hands and flopped my foot onto the gas pedal. Don’t drive cars? Don’t fly? Don't ride motorcycles?

A fine state of affairs, and me with the entire product of my life’s labor tied up in six motorcycles, a racing car and an airplane. I looked down at my useless ankle and wondered how so many things could be so dependent upon the correct function of a single conduit of ganglia running to a single joint in my ankle.

I let out a sigh and said, “Yes, sir, without muh right leg ah'd be dead.” Okay, not dead, exactly. In the world of real injuries this was pretty small-time stuff, but unless that foot started getting telegraph messages from the brain again, it would certainly change my habits and slow me down. What usually came easy would now be harder to do, and some things would not be possible.

As it turned out, the ankle gradually recovered. Within two weeks most of the feeling was back, and by the end of two months I had enough control to walk without consciously flinging my right foot out ahead of me. Two more months and the ankle brace came off.

Now, six months later, I can ride, drive and fly just fine, and walk without a limp. Still, the strength is not quite back, and there’s a different sound to the way my right foot hits the pavement. If I crouch next to a bike to check the oil or tire pressure, there’s a mild electrical sensation in the nerve.

To eliminate the crouching problem, a few weeks ago I bought one of those neat rolling stools with castors, like the one I had when I worked as a car mechanic. Also, I’ve decided to either build or buy a lift platform, the kind the pros use to lift a motorcycle up to a civilized working height.

In all, the foot problem has been an interesting little experience. That residual tingling of the nerve, always there as a reminder, has given me a serious case of renewed appreciation for good health. It has also reminded me how much it means to be able to ride motorcycles at all.

Last Sunday morning I took the Triumph out on my favorite backroad, and I found myself feeling particularly cheerful as I used that right foot to click up through the gears. Still, I couldn’t help thinking that maybe the bike and I have finally hit some kind of crossover point.

While I am still slightly damaged goods, the Triumph is now fully restored, just like new. My motorcycle, it seems, is getting younger, while I'm getting older. And I’ve been hit with the sobering realization that, for all of our cruel jokes, it may actually be possible for a British bike to be more reliable than its owner. In fact, it’ll probably be running fine long after I’m gone. Just like Elvis’s Harleys. 101

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

March 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

March 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupRenaissance of Laverda

March 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupBuilding Your Own Beemer

March 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

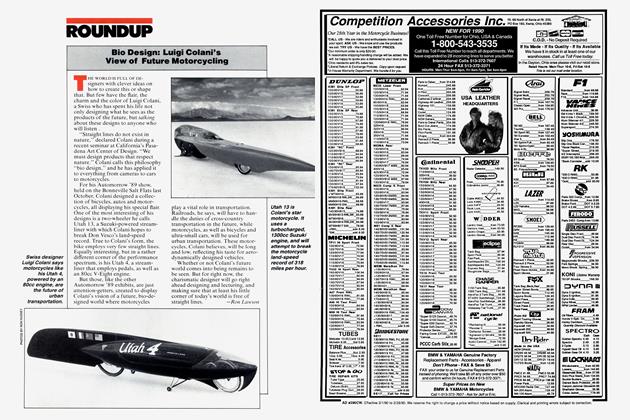

RoundupBio Design: Luigi Colani's View of Future Motorcycling

March 1990 By Ron Lawson