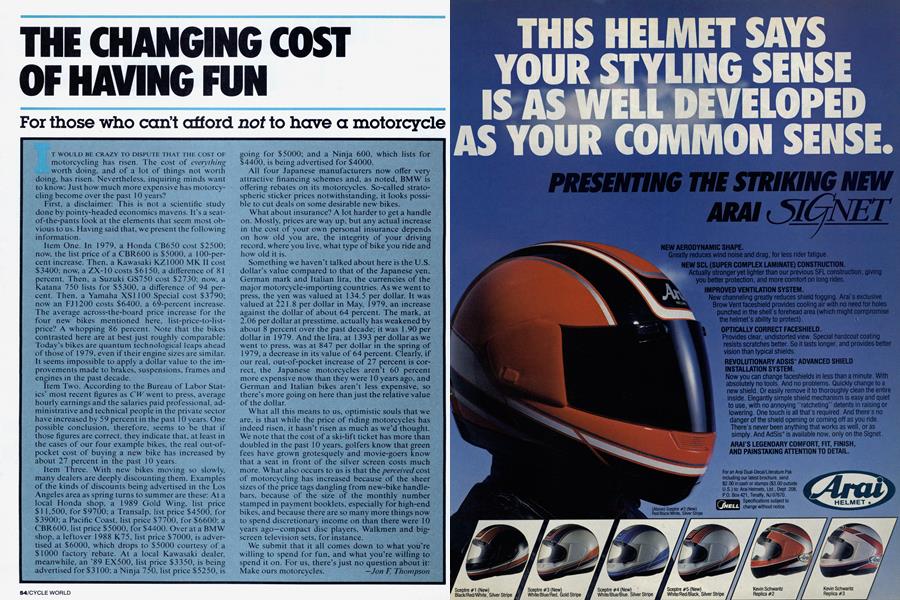

THE CHANGING COST OF HAVING FUN

For those who can’t afford not to have a motorcycle

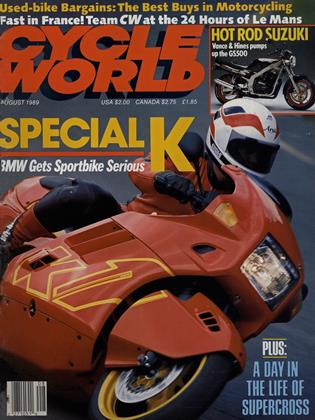

IT WOULD BE CRAZY TO DISPUTE THAT THE COST OF motorcycling has risen. The cost of everything worth doing, and of a lot of things not worth doing, has risen. Nevertheless, inquiring minds want to know: Just how much more expensive has motorcycling become over the past 10 years?

First, a disclaimer: This is not a scientific study done by pointy-headed economics mavens. It's a seat-of-the-pants look at the elements that seem most obvious to us. Having said that, we present the following information.

Item One. In 1979. a Honda CB650 cost $2500; now, the list price of a CBR600 is $5000, a 100-percent increase. Then, a Kawasaki KZ1000 MK II cost $3400; now, a ZX-10 costs $6150, a difference of 81 percent. Then, a Suzuki GS750 cost $2730; now, a Katana 750 lists for $5300, a difference of 94 percent. Then, a Yamaha XS1 100 Special cost $3790; now an FJ1200 costs $6400, a 69-percent increase. The average across-the-board price increase for the four new bikes mentioned here, list-price-to-listprice? A whopping 86 percent. Note that the bikes contrasted here are at best just roughly comparable: Today’s bikes are quantum technological leaps ahead of those of 1979, even if their engine sizes are similar. It seems impossible to apply a dollar value to the improvements made to brakes, suspensions, frames and engines in the past decade.

Item Two. According to the Bureau of Labor Statics’ most recent figures as CM7 went to press, average hourly earnings and the salaries paid professional, administrative and technical people in the private sector have increased by 59 percent in the past 10 years. One possible conclusion, therefore, seems to be that if those figures are correct, they indicate that, at least in the cases of our four example bikes, the real out-ofpocket cost of buying a new bike has increased by about 27 percent in the past 10 years.

Item Three. With new bikes moving so slowly, many dealers are deeply discounting them. Examples of the kinds of discounts being advertised in the Los Angeles area as spring turns to summer are these: At a local Honda shop, a 1989 Gold Wing, list price $ 1 1,500, for $9700; a Transalp, list price $4500, for $3900; a Pacific Coast, list price $7700, for $6600; a CBR600, list price $5000, for $4400. Over at a BMW shop, a leftover 1988 K75, list price $7000, is advertised at $6000, which drops to $5000 courtesy of a $1000 factor)' rebate. At a local Kawasaki dealer, meanwhile, an '89 EX500, list price $3350, is being advertised for $3100: a Ninja 750, list price $5250, is going for $5000; and a Ninja 600, which lists for $4400, is being advertised for $4000.

All four Japanese manufacturers now offer very attractive financing schemes and, as noted, BMW is offering rebates on its motorcycles. So-called stratospheric sticker prices notwithstanding, it looks possible to cut deals on some desirable new bikes.

What about insurance? A lot harder to get a handle on. Mostly, prices are way up, but any actual increase in the cost of your own personal insurance depends on how old you are, the integrity of your driving record, where you live, what type of bike you ride and how old it is.

Something we haven’t talked about here is the U.S. dollar’s value compared to that of the Japanese yen, German mark and Italian lira, the currencies of the major motorcycle-importing countries. As we went to press, the yen was valued at 134.5 per dollar. It was valued at 221.8 per dollar in May, 1979, an increase against the dollar of about 64 percent. The mark, at 2.06 per dollar at presstime, actually has weakened by about 8 percent over the past decade; it was 1.90 per dollar in 1979. And the lira, at 1393 per dollar as we went to press, was at 847 per dollar in the spring of 1979, a decrease in its value of 64 percent. Clearly, if our real, out-of-pocket increase of 27 percent is correct, the Japanese motorcycles aren’t 60 percent more expensive now than they were 10 years ago, and German and Italian bikes aren’t less expensive, so there’s more going on here than just the relative value of the dollar.

What all this means to us, optimistic souls that we are, is that while the price of riding motorcycles has indeed risen, it hasn’t risen as much as we’d thought. We note that the cost of a ski-lift ticket has more than doubled in the past 10 years, golfers know that green fees have grown grotesquely and movie-goers know that a seat in front of the silver screen costs much more. What also occurs to us is that the perceived cosi of motorcycling has increased because of the sheer sizes of the price tags dangling from new-bike handlebars, because of the size of the monthly number stamped in payment booklets, especially for high-end bikes, and because there are so many more things now to spend discretionary income on than there were 10 years ago—compact disc players, Walkmen and bigscreen television sets, for instance.

We submit that it all comes down to what you’re willing to spend for fun, and what you’re willing to spend it on. For us, there’s just no question about it: Make ours motorcycles.

Jon F. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

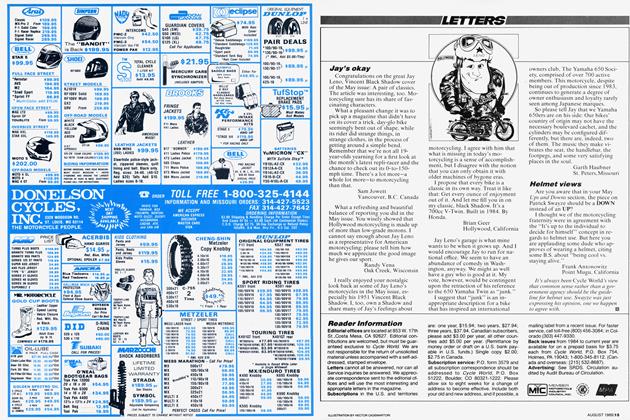

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards