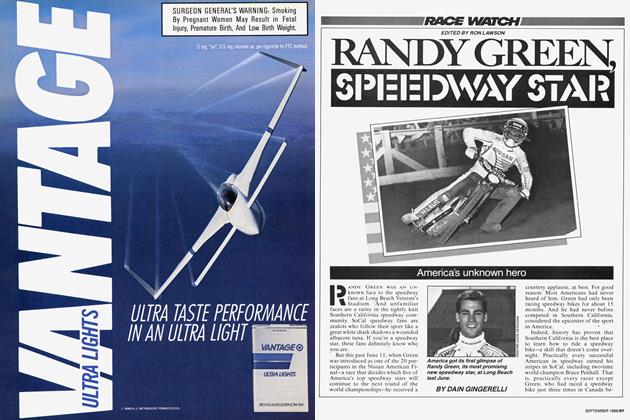

STRANGER in a STRANGE LAND

RACE WATCH

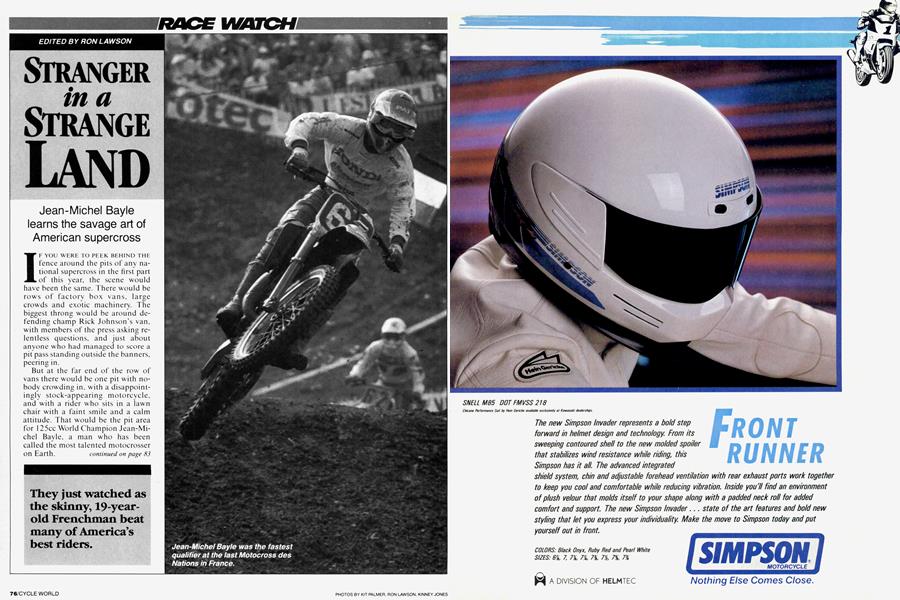

Jean-Michel Bayle learns the savage art of American supercross

RON LAWSON

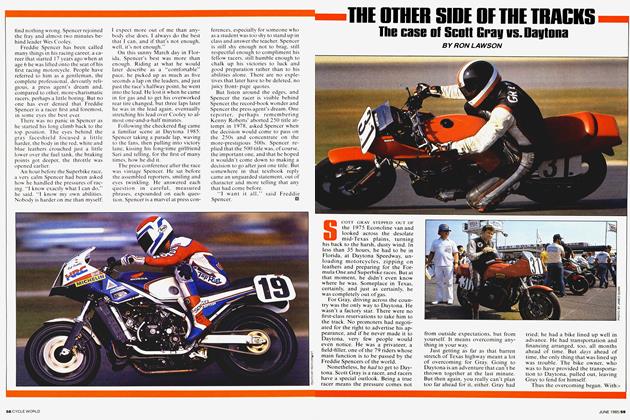

IF YOU WERE TO PEEK BEHIND THE fence around the pits of any national supercross in the first part of this year, the scene would have been the same. There would be rows of factory box vans, large crowds and exotic machinery. The biggest throng would be around defending champ Rick Johnson's van, with members of the press asking relentless questions, and just about anyone who had managed to score a pit pass standing outside the banners, peering in.

But at the far end of the row of vans there would be one pit with no body crowding in, with a disappoint ingly stock-appearing motorcycle. and with a rider who sits in a lawn chair with a faint smile and a calm attitude. That would be the pit area for 125cc World Champion Jean-Mi chel Bayle. a man who has been called the most talented motocrosser on Earth.

continued on page 83

They just watched as the skinny, 19-yearold Frenchman beat many of America's best riders.

Few observers would question that Bayle has at least as much raw talent as RickJohnson.

In the stands, the fans would anxiously await the race, confident that they were going to see the best riders in the world. But few of them would know that Bayle was going to be there, and even fewer would care. For the last 10 years, Americans have been rather smug when it comes to motocross—eight consecutive Motocross des Nations victories have a way of bolstering confidence. But if you were looking at the faces of some of those fans after the racing had begun, you would have seen a lot of that confidence disappear. Those faces just watched as the skinny, 19-yearold Frenchman beat many of America’s best riders.

But to the more knowlegable motocross fans, Bayle has already proven how fast he can go. At the Undadilla Motocross des Nations in 1987. he was clearly the fastest 125cc rider on the track, but crashes and an eventual disqualification for receiving outside assistance gave the win to Bob Hannah. At the des Nations a year later, when it was held in France, he was the fastest qualifier, despite riding a 1 25 and being timed against 250s and 500s. The course was a clas sic Open-bike track with long straights and steep uphills. But Bayle and his 1 25 qualified faster than any one, including Jeff Ward, Ron Lechien and Rick Johnson. In the race, once again, a crash kept him from winning. But, if you can believe the likes of five-time world champion Roger Dc Coster, Bayle is the world's most talented motocrosser, and just needs to develop the strength and ex perience it takes to stay on two wheels.

• . . that leaves one goal. Bayle wants to win in the United States, too.

Bayle comes from northern France, where he worked his way through that country's extensive youth motocross program. First, he became the French mini champion, then barely missed becoming the Junior champion (for riders between 16 and 18 years old) because of an injury. From there, he set his sights on the I25cc world championship, which he won for Honda in 1988. That year, he and Dutchman Dave Stribos were the only two riders to win in the l 2-race series.

But what sets Bayle apart from other European riders are his attitude and his goals. If you ask any other European rider where he would like his career to go. chances are he will say that he wants to be world champion. At 19. though, Bayle has already done that, and he's heavily favored to win the 250cc world championship in the upcoming season. That leaves one goal: He wants to be a winner in the United States, too.

That’s not easy. For one thing, Bayle himself acknowledges that there are more good riders in the U.S. than in Europe. Eor another, Honda pays him to race in Europe, not America. That means when he comes over here, he pays his own way, and he has to scrounge for support like any other privateer.

In fact, the only advantage that Bayle has in this country is the friendship of Roger De Coster. “It’s a bad situation,” De Coster laments. “When Rick Johnson goes to Europe, the French Honda importer does everything for us. But when Bayle comes to the United States, American Honda doesn’t help at all.” De Coster knows how badly Bayle wants to race in this country, though, and worked to pave the way. The first stop was at Pro Circuit, California off-road performance shop, where owner Mitch Payton was happy to supply machinery.

“The French importer for Pro Circuit sponsored Bayle earlier, and I met him at the Paris Supercross. I was impressed,” Payton says. “Roger told me that Bayle wanted to race in the U.S., and at first it looked like American Honda was going to sponsor him. But when that fell though. they came to me. I'm giving him bikes, a place for his mechanic to work, whatever it takes. He's a good kid-real easy to please." After seeing some results, Honda loaned Bayle a van (one that was used originally in the dirt-track program) and some works suspension parts. "He really wants to ride over here," Payton reflects. "He origi nally wanted a contract to ride in the U.S. all year. Next year he might do it.''

But Bayle himself has had to set priorities. “Right now. there's a lot of pressure on me to win the 250 world championship,” he says. “After that, who knows. Maybe I will come to the U.S.” As it stands now, he will go back to Europe after the Daytona Supercross, racing in only seven of the 15 races in the supercross series. But after the first five of those, he stands in sixth place in the points.

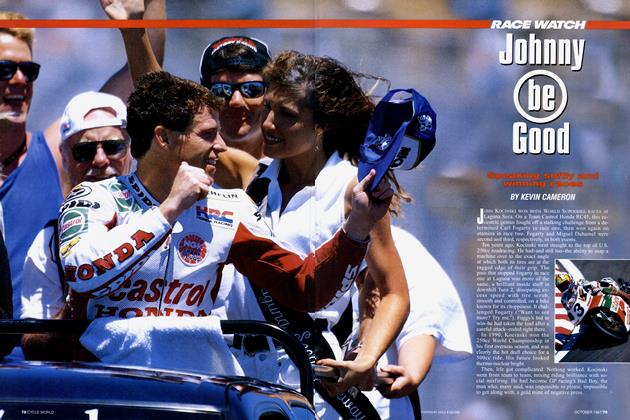

Considering that no European has ever finished in the top 10 in the final standings since Sweden's Jan-Eric Sallquist finished eighth in the threerace series of 1975, and that only a handful of Euros have ever made the final in a supercross, Bayle's accomplishments are even more impressive. Racing in the tight confines of a stadium course are like nothing he’s done before, but it's taken him little time to adapt. Every time he rides, he learns a little more. In two of his first American stadium races, he crashed in the first turn, unused to the aggres-> siveness of the Americans. In his most recent, he was second to Rick Johnson.

Comparisons to Johnson are inevitable. Few observers would question that Bayle has at least as much raw talent as Johnson. But Johnson has talent and an unshakable desire to win. “Johnson does whatever it takes to win,” says Payton. “It isn't very pretty sometimes—he'll ride over his head or whatever it takes. But if he can see the rider in front of him, he'll win. Bayle rides like Ron Lechien did a few years ago, real fluid and relaxed. In Europe, he’s used to racing against one or two fast guys. Over here, there are four or five riders who don’t mind hitting you.”

Bayle doesn't see his quick adaptation to supercross as anything unusual. Even double-jumps, which are banned in Europe, don't present much of a problem for him. “I practice double-jumps all the time at home. And on sand tracks, the whoops get so large that they are double-jumps.”

Even though Bayle is learning the brutal art of American racing rather quickly, he will have to put a hold on his lessons and return to Europe soon. There, a full-works Honda 250 awaits him, as well as thousands of adoring French motocross fans, fa miliar food, and his native customs and language. There, he will go about his business of winning world cham pionships. But all the while, he will be thinking and planning for another trip to the U.S., this time, to perhaps race the entire supercross series. Because while racing in Europe in the GPs is what Jean-Michel Bayle does for a living, racing in the U.S. is what he does for fun.

For now.