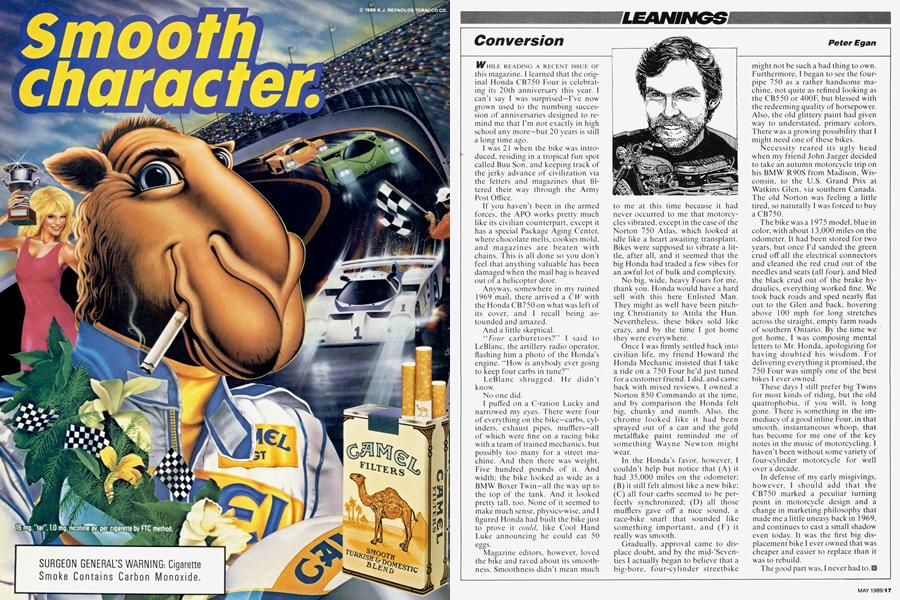

LEANINGS

Conversion

Peter Egan

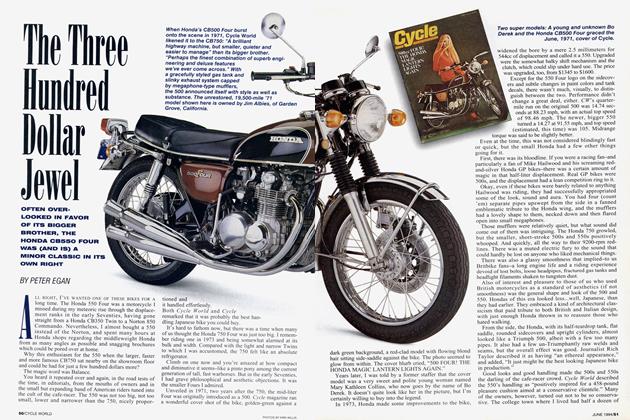

WHILE READING A RECENT ISSUE OF this magazine, I learned that the original Honda CB750 Four is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. I can’t say I was surprised—I've now grown used to the numbing succession of anniversaries designed to remind me that I’m not exactly in high school any more—but 20 years is still a long time ago.

I was 21 when the bike was introduced, residing in a tropical fun spot called Buu Son, and keeping track of the jerky advance of civilization via the letters and magazines that filtered their way through the Army Post Office.

If you haven’t been in the armed forces, the APO works pretty much like its civilian counterpart, except it has a special Package Aging Center, where chocolate melts, cookies mold, and magazines are beaten with chains. This is all done so you don’t feel that anything valuable has been damaged when the mail bag is heaved out of a helicopter door.

Anyway, somewhere in my ruined 1969 mail, there arrived a CW with the Honda CB750 on what was left of its cover, and I recall being astounded and amazed.

And a little skeptical.

“Four carburetors?” I said to LeBlanc, the artillery radio operator, flashing him a photo of the Honda’s engine. “How is anybody ever going to keep four carbs in tune?”

LeBlanc shrugged. He didn't know.

No one did.

I puffed on a C-ration Lucky and narrowed my eyes. There were four of everything on the bike—carbs, cylinders, exhaust pipes, mufflers—all of which were fine on a racing bike with a team of trained mechanics, but possibly too many for a street machine. And then there was weight. Five hundred pounds of it. And width; the bike looked as wide as a BMW Boxer Twin—all the way up to the top of the tank. And it looked pretty tall, too. None of it seemed to make much sense, physics-wise, and I figured Honda had built the bike just to prove it could, like Cool Hand Luke announcing he could eat 50 eggs.

Magazine editors, however, loved the bike and raved about its smoothness. Smoothness didn't mean much to me at this time because it had never occurred to me that motorcycles vibrated, except in the case of the Norton 750 Atlas, which looked at idle like a heart awaiting transplant. Bikes were supposed to vibrate a little, after all, and it seemed that the big Honda had traded a few vibes for an awful lot of bulk and complexity.

No big, wide, heavy Fours for me, thank you. Honda would have a hard sell with this here Enlisted Man. They might as well have been pitching Christianity to Attila the Hun. Nevertheless, these bikes sold like crazy, and by the time I got home they were everywhere.

Once I was firmly settled back into civilian life, my friend Howard the Honda Mechanic insisted that I take a ride on a 750 Four he’d just tuned for a customer friend. I did, and came back with mixed reviews. I owned a Norton 850 Commando at the time, and by comparison the Honda felt big, chunky and numb. Also, the chrome looked like it had been sprayed out of a can and the gold metalflake paint reminded me of something Wayne Newton might wear.

In the Honda's favor, however, I couldn’t help but notice that (A) it had 35,000 miles on the odometer;

(B) it still felt almost like a new bike;

(C) all four carbs seemed to be perfectly synchronized; (D) all those mufflers gave off a nice sound, a race-bike snarl that sounded like something important, and (F) it really was smooth.

Gradually, approval came to displace doubt, and by the mid-’Seventies I actually began to believe that a big-bore, four-cylinder streetbike might not be such a bad thing to own. Furthermore, I began to see the fourpipe 750 as a rather handsome machine, not quite as refined looking as the CB550 or 400F, but blessed with the redeeming quality of horsepower. Also, the old glittery paint had given way to understated, primary colors. There was a growing possibility that I might need one of these bikes.

Necessity reared its ugly head when my friend John Jaeger decided to take an autumn motorcycle trip on his BMW R90S from Madison, Wisconsin, to the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, via southern Canada. The old Norton was feeling a little tired, so naturally I was forced to buy a CB750.

The bike was a 1975 model, blue in color, with about 13,000 miles on the odometer. It had been stored for two years, but once I’d sanded the green crud off all the electrical connectors and cleaned the red crud out of the needles and seats (all four), and bled the black crud out of the brake hydraulics, everything worked fine. We took back roads and sped nearly flat out to the Glen and back, hovering above 100 mph for long stretches across the straight, empty farm roads of southern Ontario. By the time we got home, I was composing mental letters to Mr. Honda, apologizing for having doubted his wisdom. For delivering everything it promised, the 750 Four was simply one of the best bikes I ever owned.

These days I still prefer big Twins for most kinds of riding, but the old quatrophobia, if you will, is long gone. There is something in the immediacy of a good inline Four, in that smooth, instantaneous whoop, that has become for me one of the key notes in the music of motorcycling. I haven’t been without some variety of four-cylinder motorcycle for well over a decade.

In defense of my early misgivings, however, I should add that the CB750 marked a peculiar turning point in motorcycle design and a change in marketing philosophy that made me a little uneasy back in 1969, and continues to cast a small shadow even today. It was the first big displacement bike I ever owned that was cheaper and easier to replace than it was to rebuild.

The good part was, I never had to.