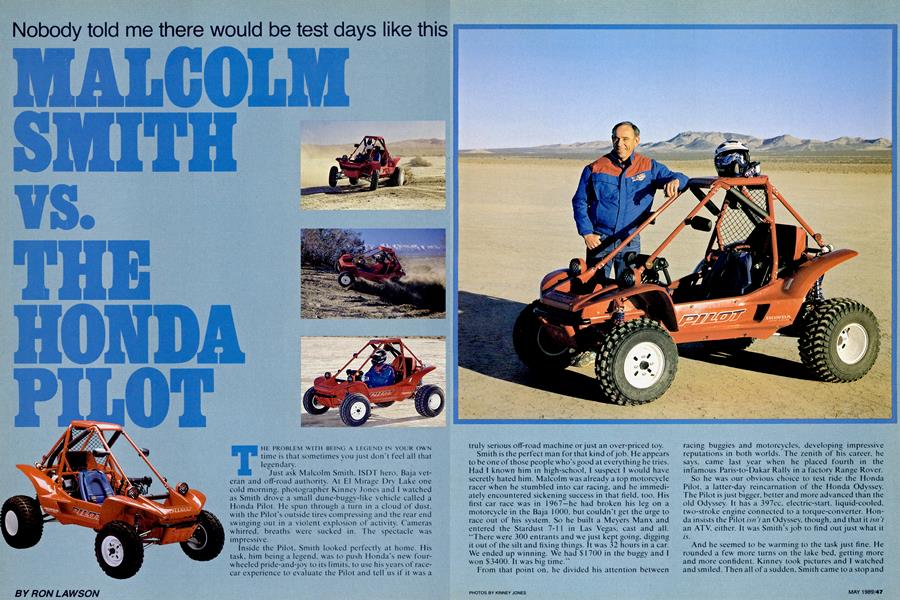

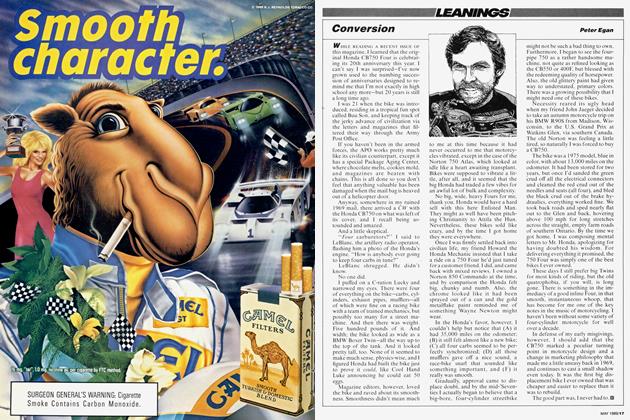

MALCOLM SMITH VS. THE HONDA PILOT

Nobody told me there would be test days like this

RON LAWSON

THE PROBLEM WITH BEING A LEGEND IN YOUR OWN time is that sometimes you just don't feel all that legendary.

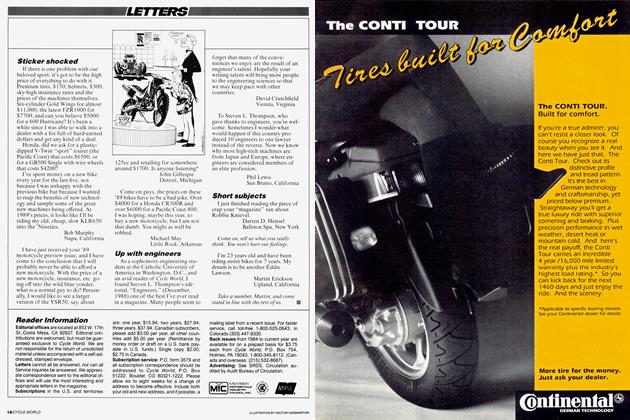

Just ask Malcolm Smith, ISDT hero. Baja veteran and off-road authority. At E1 Mirage Dry Lake one cold morning, photographer Kinney Jones and I watched as Smith drove a small dune-buggv-like vehicle called a Honda Pilot. He spun through a turn in a cloud of dust, with the Pilot's outside tires compressing and the rear end swinging out in a violent explosion of activity. Cameras whirred, breaths were sucked in. The spectacle was impressive.

Inside the Pilot, Smith looked perfectly at home. His task, him being a legend, was to push Honda's new fourwheeled pride-and-joy to its limits, to use his years of'racecar experience to evaluate the Pilot and tell us if it was a truly serious off-road machine or just an over-priced toy.

Smith is the perfect man for that kind of job. He appears to be one of those people who's good at everything he tries. Had I known him in high-school, I suspect I would have secretly hated him. Malcolm was already a top motorcycle racer when he stumbled into car racing, and he immediately encountered sickening success in that field, too. His first car race was in 1967—he had broken his leg on a motorcycle in the Baja 1000. but couldn't get the urge to race out of his system. So he built a Meyers Manx and entered the Stardust 7-1 1 in Las Vegas, cast and all. “There were 300 entrants and we just kept going, digging it out of the silt and fixing things. It was 32 hours in a car. We ended up winning. We had $ 1 700 in the buggy and I won $3400. It was big time."

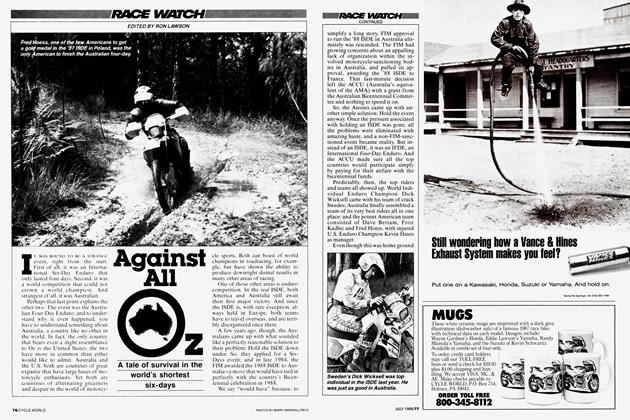

From that point on. he divided his attention between racing buggies and motorcycles, developing impressive reputations in both worlds. The zenith of his career, he says, came last year when he placed fourth in the infamous Paris-to-Dakar Rally in a factory Range Rover.

So he was our obvious choice to test ride the Honda Pilot, a latter-day reincarnation of the Honda Odyssey. The Pilot is just bigger, better and more advanced than the old Odyssey. It has a 397cc. electric-start, liquid-cooled, two-stroke engine connected to a torque-converter. Honda insists the Pilot isn't an Odyssey, though, and that it isn't an ATV. either. It was Smith's job to find out just w hat it is.

And he seemed to be warming to the task just fine. He rounded a few more turns on the lake bed. getting more and more confident. Kinney took pictures and I watched and smiled. Then all of a sudden. Smith came to a stop and just sat there, not saying a word. We walked up to the Pilot as the lingering dust began to settle and peered inside. 1 was expecting a few words of perfect insight, a tiny capsule of wisdom that might be suitable for a headline. I waited anxiously, and then Malcolm Smith, ÍSDT legend, Baja veteran and off-road authority, began to speak. He said: “1 think I'm going to be sick.”

I thought he was joking at first, but a look at his queasy face told me he wasn’t. Kinney and I took a few1 steps back with "Oh, don’t mind us.” looks on our faces. Kinney pretended to take a light reading and I got real interested in my shoelaces, but there's only so much privacy that you can offer a man when you’re standing in the middle of a perfectly featureless dry lake bed. Smith slowly recovered, his face once again becoming face-colored. He still might not have felt like a legend, but I believe he began to at least feel human again.

That’s when Kinney, the photographer, surprised me. Kinney, you see. has worked for Smith for years at MS Products, and more or less views him as his personal mentor. Even though he was working for Cycle World at that particular moment, I half expected Kinney to act real protective on Smith's behalf, to put an end to the test session right then and to whisk Smith back home.

But instead, Kinney walked up to the Pilot where Smith still sat. and asked with a straight face, "Ready for a few' more passes?” My jaw dropped. Malcolm just nodded, then fired up the Pilot with waning enthusiasm.

Five minutes later, the Pilot stopped, and once again Smith had turned that same shade of green. Kinney looked at his watch impatiently, told Malcolm to take a fiveminute break, and loaded up some more film. The entire process was repeated. Over and over. I didn’t really want to intervene—I mean, these two were close friends, or at least I thought they were close friends. Unless there was some hidden animosity between them that I didn't know about, they should know what’s best.

The truth, I later learned, was that this was nothing unusual. Malcolm Smith. ISDT hero, Baja veteran, etc., as it happens, gets motion sickness. It's hit him in Baja while he’s been leading races, and it hits him in the backseat of passenger cars. To him. it's just no big deal. But that didn’t mean he was any less incapacitated that day at El Mirage. After a few hours of stop-and-go driving. Smith finally had had enough. He kind of oozed out of the Pilot and laid dow n, helmet and goggles still in place. It was obvious that he was done. Kinney, however, wasn't. He had that look a dedicated photographer gets when he’s still looking for The Shot. "Ron,” he said, turning his back on the nowuseless lump of humanity that used to be Malcolm Smith, "You can drive this thing, can't you? Let’s see you do a few passes.” Malcolm just waved his arm in a "Leave me here, save yourselves” sort of way. Wonderful. Smith was Kinney’s close and dear personal friend. What did he have in mind for me?

Ten minutes later, I found out. “A double-jump?” I asked incredulously.

"It’s not really a double-jump.” Kinney responded, as if to say, "It's not really a hand grenade—see here, pull the pin.” He continued, "It’s just a little plateau. You can't get hurt inside that thing anyway. Shoot. I'd do it.” That was below the belt. But I had to admit, he had a point. The Pilot is completely enclosed in a substantial-looking rollcage. When I finally developed enough nerve to try the double. I learned that I had nothing to be afraid of. The Pilot has fairly serious suspension. While the old Odyssey just had simple shocks and sw ingarms, the Pilot has fourwheel. double-wishbone, independent suspension. It landed impressively smoothly.

It wasn’t until the section of two-foot-tall whoops that Kinney made me go through that I exceeded the limit of the suspension. The Pilot would start rocking front to back, rattling my head around and damn near making me motion sick. But that wasn’t nearly as bad as the off-camber. side-hill section that Kinney wanted me to cross. Strapped into the Pilot, I couldn’t use body English to counter the slope’s angle—very much ////like a motorcycle or ATV. It made me feel real helpless.

Where the Pilot is the most fun. I discovered, is on the flat and smooth stuff that had totalled out Malcolm. You can just pitch the thing sideways, without any concern about getting too radical. The Pilot lets you do all those things that you fantasize about doing in the family station wagon. Even if you do get too crazy and put the Pilot on its head, it’s just a matter of climbing out and tipping it back over. The driver is strapped in tight and there are even wrist restraints to keep him from putting out his hands.

One thing that seems strange about the Pilot, though, is its sound—it’s all wrong. Because of the slippage in the torque converter, it revs fairly high at low speed. But at higher speed, the rpm drops considerably—it's all backwards. But the Pilot’s low-end power is great, and even if it sounds like it’s idling at high speed, it actually has plenty of power on top. too.

I was having great fun. When Kinney was done with me, I circled the van a few times where Smith was still laying. I slid to a stop, at which time Malcolm expressed his warm gratitude for the dust I kicked up. It was obvious that he was feeling better.

As I got unstrapped, he asked me what I thought of the Pilot. “Sometimes, it’s about as much fun as you can stand,“ I replied. “But it’s limited. It's not always that great.”

Smith nodded. “There’s a slight similarity between driving this thing and driving a buggy about 1 5 years ago.” he offered. “Then, buggies were shorter and had less wheel travel than they do now.”

I asked how similar the Pilot was to a modern off-road race car. Malcolm just shook his head. “Not very. Buggies have come a long way. They're like motorcycles. Imagine a 1972 motorcycle compared to one now. Buggies have done that. The Pilot would actually be pretty similar to the car I built in 1967—about the same amount of travel. But the Manx was longer, and it went through the bumps better. The Pilot’s fun, though. It's a great, fun, toy. And they would be real fun to race against each other. I think if I had one of them, there are a lot of things I'd like to do. I’d see if I could make it longer and wider. And I’d put a foot throttle in it—I had a hard time working all the controls with my hands while I was steering.”

As we were loading up all the various gas cans and gear bags, I offered to lend Malcolm the Pilot for a weekend. He looked at it, and just a twinge of that greenish color started to return, mostly in his ears. “No, maybe not." he replied. “I get motion sickness real easy, and nothing gives it to me quite as fast as that thing.”

Then he thought about it some. “You know, my doctor does have several different air-sick pills he wants me to try. Maybe I should take a handful of them and go out testing with the Pilot ...

I just shrugged and tried to fight back a smile. For me, Malcolm Smith will always be a legend—he embodies everything that I believe a racer should be.

But there was something strangely comforting in discovering that even legends are human.