AT LARGE

Honda Time

Steven L. Thompson

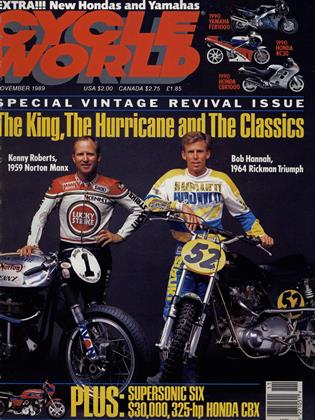

I SPOTTED THE BLACK HONDA CBX A block away. It was parked on the side-walk among the politically correct organic boutiques of Church Street in San Francisco’s Noe Valley, and its sheer mechanical audacity, its outrageous six-cylinder haughtiness, so unlike the slicked-down, tucked-away superbikes of today, was enough to make me smile. Church Street being what it is, nobody paid much attention to the old Honda. But I did. I stopped to admire, for the first time in a decade, it seemed, Mr. Shoichiro Irimajiri’s masterpiece of motorcycle sculpture. By chance, the bike’s owner arrived at his bike as I was relishing old CBX memories.

“Nice CBX,” I ventured, and the inevitable curbside discussion was on. Why a CBX? I asked.

I already knew, by watching the upward creep of CBX prices in the classifieds, that the massive Six had passed through its dirt-cheap period and was now on a steady but still modest price climb. And I knew a couple of people who’d suddenly rediscovered a longing for one. Recent magazine articles likewise rediscovering the bike also told of a groundswell of interest in the machine. But this street meeting with a True Believer was my first encounter with someone too young to have ridden the bike when it appeared, and, maybe inevitably, I wondered if this CBX price escalation was the beginning of the long-awaited All-Japanese Nostalgia Boom.

Nah. This was just a guy who liked CBXs. At least, that was how it seemed at first. But as the youngish computer programmer told me about his landmark motorcycles, I realized that we shared something else besides fondness for the Six: Honda Time.

In spite of the fact that I have only owned one Honda (a 1964 CB77, now on permanent loan to Lex DuPont’s museum at New Garden Airport in Toughkenamon, Pennsylvania), I’ve ridden more than I can count. Mostly that’s due to a career in the auto/moto magazine biz. But also it’s due to the sheer power of Honda.

Last year, I stood in the immaculate, semi-restricted Honda Museum below the company bowling alley at the Suzuka Circuit in Japan, transfixed by memories of motorcycles and cars that had stamped themselves on my memory. I wandered the quiet, carpeted aisles, between rows of motorcycles each of which seemed to remind me, like so many contemporaneous pop songs, not just of broad eras, but of specific seasons of the years, year after year. This was Honda Time.

Everyone has markers, of course, for the passage of his/her time. Graduation. The military. Marriage. Divorce. Births. Deaths. But the machines we notice—even if we don’t buy them—serve as milestones in the looping, crazy, Moebius strip of time. And who, besides those who have locked themselves inside some form of marque-worship, has been able to ignore Hondas? Not I, despite my abstention from buying them.

So the CBX on the San Francisco street reminded me of more than itself, although it was powerfully evocative in itself. I was reminded how it was the centerpiece of the “hyperbike” test which kicked off, in the November, 1978, issue, the redesign of Cycle Guide magazine I had been asked to honcho as Editorial Director: about the long, hot, wonderful “shootout” ride that I, Paul Dean, Michael Jordan and Jeff Karr had shared up and down the spine of California as we wrung out the CBX, Kawasaki Zl-R, Yamaha XS11 and Suzuki GS1000E. To the extent that we established, with that story, a small part of the lore of the CBX, seeing that bike appreciated by a man too young to buy it H years ago gave me a strong sense of the passage and the power of Honda Time.

No matter how old you are, you have a Honda as a time-hack. Born in 1920, were you? Then you remember, when you were assigned to the Occupation Forces in Tokyo, how the “indigenous personnel” rode around on Honda Cubs, little more than bicycles with strap-on engines. Born in 1930? You were there when the word “Honda” became synonymous with “little motorbike.” 1940? You probably rode a Super Cub in school, and “moved up” to a CL72 Scrambler with Snuf-R-Nots. 1950? You lusted after—or were scornful of—the then-awesome 750 Four. 1960? You rode Elsinores in high school and later put a Kerker on the twin-cam Four. 1970? You pasted pictures of the VF750F on your history book in junior high. Or maybe it was the ATC. And if you’re a touring rider, no matter when you were born or what you ride, the Gold Wing has been the standard since 1975.

None of this is to say other manufacturers haven’t turned out landmark machines. Obviously they have; that’s one reason they’ve remained in business, selling riders like me motorcycles. My benchmarks include motorcycles made by every manufacturer from AJS to Zundapp, and maybe two dozen of them stand out as exemplars of this or that specialty. But when I try to place them in memory, to connect them with their time and place, their time zones are always anchored by Hondas.

In a way, this is an ironic aspect of Honda’s staggering productivity and seemingly inexhaustible ingenuity. “Too many models too often!” has been a charge leveled against Honda for most of the last 20 years, usually accompanied by the accusation that such a pace of change results in motorcycles that are annually outmoded, to be consigned to the junk pile and forgotten.

Maybe so. But don’t tell that to a certain CBX rider in San Francisco. He waited a long time to find one. And now he’s stalking a CB400F.

Remember the CB400F? Sure you do. It came out the year you....

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

Roundup

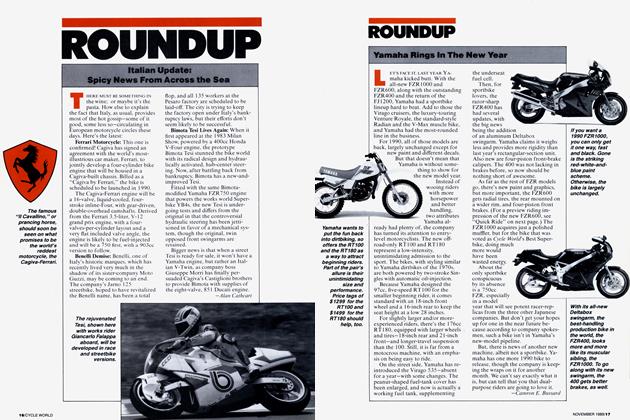

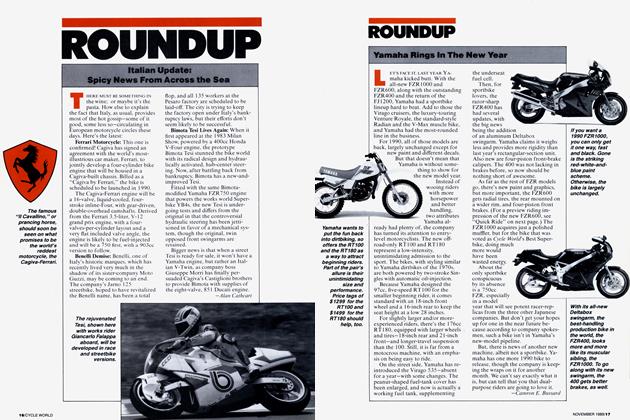

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

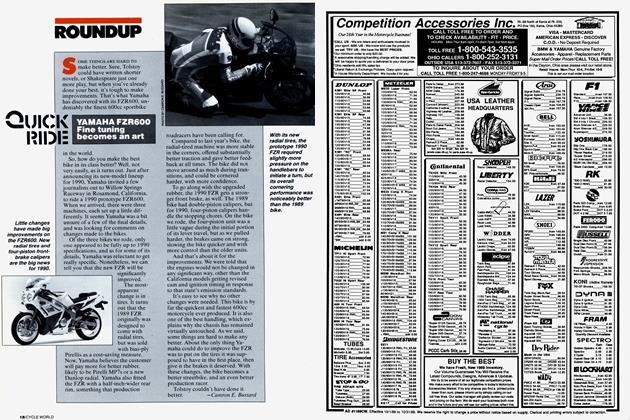

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard