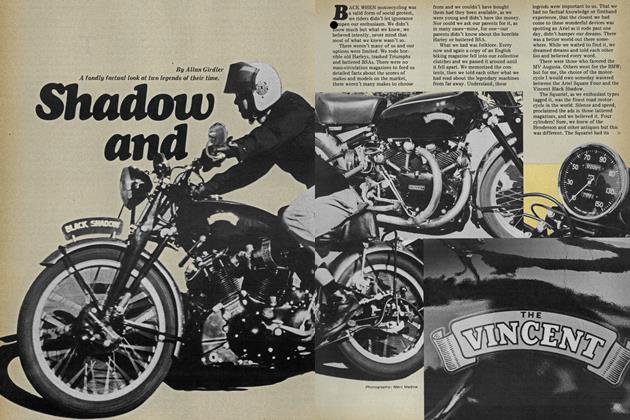

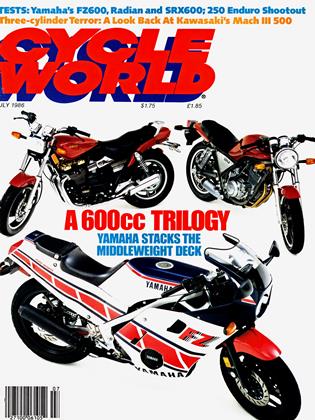

TRIPLE THREAT

Three cylinders. 500cc's worth. Two strokes.

JEFFREY HANSEN

FRANCIS GOLDEN IS A QUIET MAN. GRAYING AT THE temples. who makes wearing spectacles and a satisfied grin look as appealing as an old pair of Levi's. But that's only fitting, considering Golden has most of the things in life a man could want: a wonder ful wife, beautiful kids, two playful dogs. a group insurance policy, a B.S. degree from Wisconsin State and a good job in the computer field.

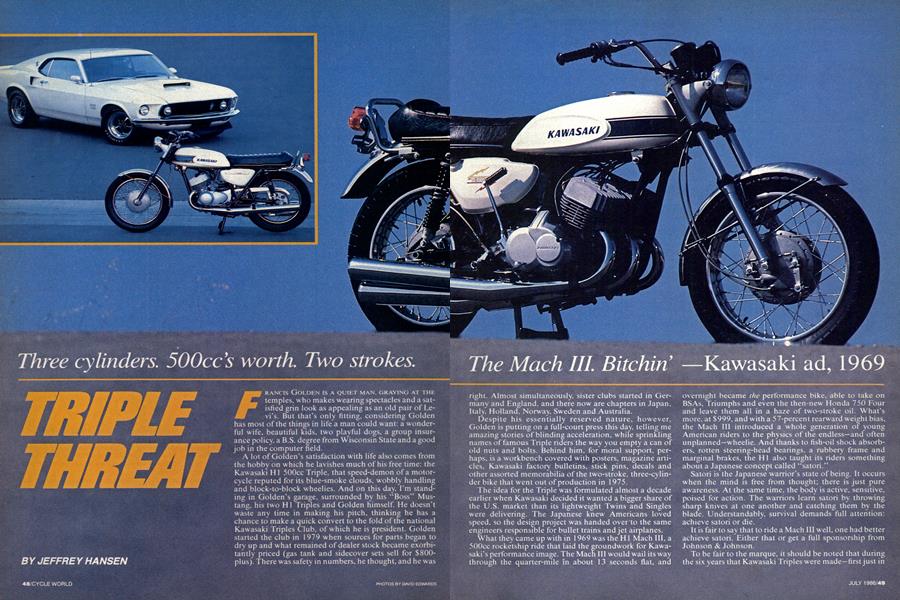

A lot of Golden's satisfaction with life also comes from the hobby on which he lavishes much of his free time: the Kawasaki H 1 500cc Triple, that speed-demon of a motor cycle reputed for its blue-smoke clouds, wobbly handling and block-to-block wheelies. And on this day. I'm stand ing in Golden's garage, surrounded by his "Boss" Mus tang. his two H 1 Triples and Golden himself. He doesn't waste any time in making his pitch. thinking he has a chance to make a quick convert to the fold of the national Kawasaki Triples Club. of which he is president. Golden started the club in 1979 when sources for parts began to dry up and what remained of dealer stock became exorbi tantly priced (gas tank and sidecover sets sell for $800plus). There was safety in numbers, he thought, and he was right. Almost simultaneously, sister clubs started in Germany and England, and there now are chapters in Japan. Italy. Holland. Norway, Sweden and Australia.

The Mach III. Bitchin' - Kawasaki ad, 1969

Despite his essentially reserved nature, however, Golden is putting on a full-court press this day. telling me amazing stories of blinding acceleration, while sprinkling names of famous Triple riders the way you empty a can of old nuts and bolts. Behind him. for moral support, perhaps, is a workbench covered with posters, magazine articles, Kawasaki factor)7 bulletins, stick pins, decals and other assorted memorabilia of the two-stroke, three-cylinder bike that w ent out of production in 1975.

The idea for the Triple was formulated almost a decade earlier when Kawasaki decided it wanted a bigger share of the U.S. market than its lightweight Twins and Singles were delivering. The Japanese knew Americans loved speed, so the design project w7as handed over to the same engineers responsible for bullet trains and jet airplanes.

What they came up w ith in 1969 was the H1 Mach III, a 500cc rocketship ride that laid the groundwork for Kawasaki's performance image. The Mach III would w7ail its way through the quarter-mile in about 13 seconds flat, and overnight became the performance bike, able to take on BSAs, Triumphs and even the then-new Honda 750 Four and leave them all in a haze of two-stroke oil. What's more, at $999. and with a 57-percent rearward weight bias, the Mach III introduced a whole generation of young American riders to the physics of the endless—and often unplanned—wheelie. And thanks to fish-oil shock absorbers, rotten steering-head bearings, a rubbery frame and marginal brakes, the HI also taught its riders something about a Japanese concept called “satori.”

Satori is the Japanese warrior's state of being. It occurs when the mind is free from thought; there is just pure awareness. At the same time, the body is active, sensitive, poised for action. The warriors learn satori by throwing sharp knives at one another and catching them by the blade. Understandably, survival demands full attention: achieve satori or die.

It is fair to say that to ride a Mach III well, one had better achieve satori. Either that or get a full sponsorship from Johnson & Johnson.

To be fair to the marque, it should be noted that during the six years that Kawasaki Triples were made—first just in 500cc form, but later in 250, 350, 400 and 750cc sizes, as well—the frames and suspensions were improved, and engine output was tamed somewhat, all in hopes of making them better all-around motorcycles. Still, when Cycle World tested the last-of-the-line 750, the bike was summed up in five words: “Evil, wicked, mean and nasty.”

Golden knows all about the Triples’ bad reputation and doesn’t put up much of an argument when the subject is broached. For the record, he says that the Triple is not now and never has been a bike for beginners, that it must be ridden aggressively and with the calm assurance that it might, at any time, reach back and bite you but good.

As a character witness, Golden introduces one Russ “Mr. Blue” Miller, a charter member of the Triples Club. Miller works at the nearby Camarillo, California, state mental hospital where he councils psychotic adolescents (and has the scars to prove it). To unwind, Miller has a marina-blue ’69 427 Corvette and, of course, a garage full of Kawasaki three-cylinder motorcycles, including his favorite, a 750 H2 that pumps out about 100 horsepower, 25 more than stock. And it seems that Miller gets good use out of his recreational vehicles. If asked, he will produce an old cigar box, into which is stuffed an impressive collection of traffic-ticket carbons. The very top one is for doing one of the dumbest things you can do—pulling a wheelie on an H2, on the freeway, in front of a California Highway Patrol officer.

But that was in 1977, and Miller says he doesn’t do crazy things like that anymore. Chalk it up to youth, he says. That, and having more guts than brains. And to hear Miller talk about the riding characteristics of the Triples, it seems a healthy dose of guts is a prerequisite.

“These bikes are not for everybody,” Miller says. “New or used, they are not bikes you want to drive around town all day. They’re a chore to ride, although they are comfortable enough, but not by much. They vibrate, they’re peaky, and not the best on gas.”

Miller continues, saying the Mach Ill’s extremely light front end has a tendency to loop, a phrase that could qualify as the understatement of the last two decades. “I think that most of the injuries that have occurred with these machines were because an unskilled rider was caught by surprise,” he says. “At 4000 rpm, the motorcycle does just fine. But at 5000 to 6000, the engine literally comes alive. It’s like hitting an afterburner switch. And if you’re not prepared for it, all of a sudden you realize that you’ve just placed yourself in jeopardy.”

Why, then, would any sane person want to own one of these three-cylinder devilbikes, much less ride it? Golden’s explanation is that, to a great extent, his interest—and that of the club’s 230 members—is to preserve a memorable piece of history in the evolution of motorcycles.

That makes pretty good sense. But somehow, it’s hard to erase the vision of Russ Miller giving his one-wheel salute to the CHP officer. That, and the way Golden and Miller both shrug off of the Mach Ill’s many and varied faults.

“If you’re a Kawasaki Triple enthusiast, well, who cares?” says Miller with complete sincerity. “Every minute on one of these things is worth it.” S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

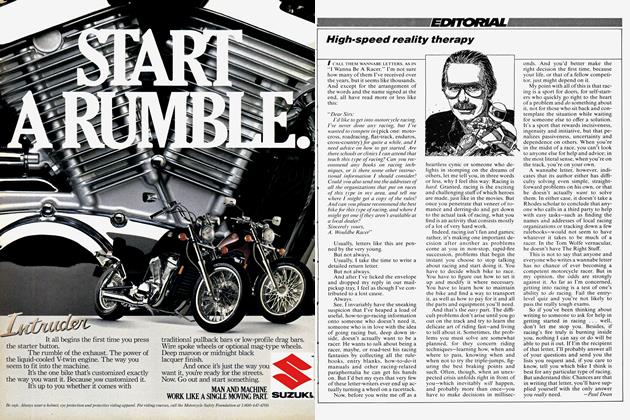

DepartmentsEditorial

July 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupSlowing the Insurance Liability Crisis

July 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

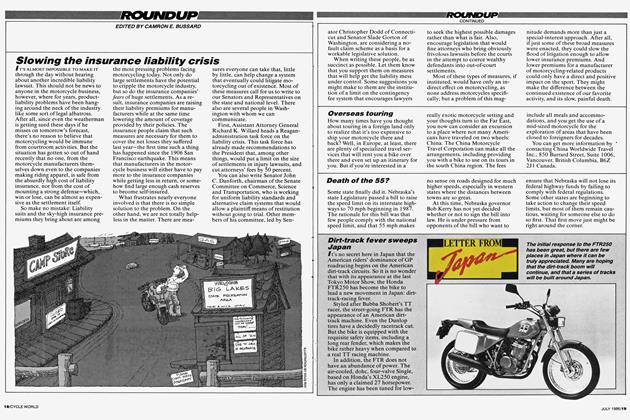

RoundupLetter From Japan

July 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Evaluation

EvaluationVetter Flagman Hi-Tech Tankbag

July 1986