Splinter Road

"TEN THOUSAND SEE BIKERS FLIRT WITH DEATH!"

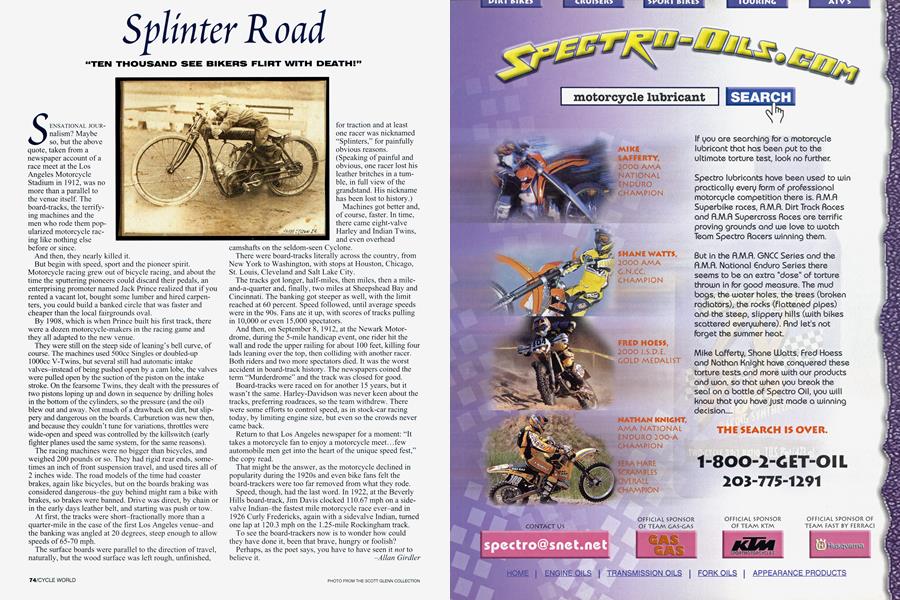

SENSATIONAL JOURnalism? Maybe so, but the above quote, taken from a newspaper account of a race meet at the Los Angeles Motorcycle Stadium in 1912, was no more than a parallel to the venue itself. The board-tracks, the terrifying machines and the men who rode them popularized motorcycle racing like nothing else before or since.

And then, they nearly killed it.

But begin with speed, sport and the pioneer spirit. Motorcycle racing grew out of bicycle racing, and about the time the sputtering pioneers could discard their pedals, an enterprising promoter named Jack Prince realized that if you rented a vacant lot, bought some lumber and hired carpenters, you could build a banked circle that was faster and cheaper than the local fairgrounds oval.

By 1908, which is when Prince built his first track, there were a dozen motorcycle-makers in the racing game and they all adapted to the new venue.

They were still on the steep side of leaning’s bell curve, of course. The machines used 500cc Singles or doubled-up lOOOcc V-Twins, but several still had automatic intake valves-instead of being pushed open by a cam lobe, the valves were pulled open by the suction of the piston on the intake stroke. On the fearsome Twins, they dealt with the pressures of two pistons loping up and down in sequence by drilling holes in the bottom of the cylinders, so the pressure (and the oil) blew out and away. Not much of a drawback on dirt, but slippery and dangerous on the boards. Carburetion was new then, and because they couldn’t tune for variations, throttles were wide-open and speed was controlled by the killswitch (early fighter planes used the same system, for the same reasons).

The racing machines were no bigger than bicycles, and weighed 200 pounds or so. They had rigid rear ends, sometimes an inch of front suspension travel, and used tires all of 2 inches wide. The road models of the time had coaster brakes, again like bicycles, but on the boards braking was considered dangerous-the guy behind might ram a bike with brakes, so brakes were banned. Drive was direct, by chain or in the early days leather belt, and starting was push or tow.

At first, the tracks were short-fractionally more than a quarter-mile in the case of the first Los Angeles venue-and the banking was angled at 20 degrees, steep enough to allow speeds of 65-70 mph.

The surface boards were parallel to the direction of travel, naturally, but the wood surface was left rough, unfinished, for traction and at least one racer was nicknamed "Splinters," for painfully obvious reasons. (Speaking of painful and obvious, one racer lost his leather britches in a tum ble, in full view of the grandstand. His nickname has been lost to history.)

iia~ U~¼~11 1~J~L ui 111~3L~JIJ.) Machines got better and, of course, faster. In time, there came eight-valve Harley and Indian Twins, and even overhead camshafts on the seldom-seen Cyclone.

There were board-tracks literally across the country, from New York to Washington, with stops at Houston, Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland and Salt Lake City.

The tracks got longer, half-miles, then miles, then a mileand-a-quarter and, finally, two miles at Sheepshead Bay and Cincinnati. The banking got steeper as well, with the limit reached at 60 percent. Speed followed, until average speeds were in the 90s. Fans ate it up, with scores of tracks pulling in 10,000 or even 15,000 spectators.

And then, on September 8, 1912, at the Newark Motordrome, during the 5-mile handicap event, one rider hit the wall and rode the upper railing for about 100 feet, killing four lads leaning over the top, then colliding with another racer. Both riders and two more spectators died. It was the worst accident in board-track history. The newspapers coined the term “Murderdrome” and the track was closed for good.

Board-tracks were raced on for another 15 years, but it wasn’t the same. Harley-Davidson was never keen about the tracks, preferring roadraces, so the team withdrew. There were some efforts to control speed, as in stock-car racing today, by limiting engine size, but even so the crowds never came back.

Return to that Los Angeles newspaper for a moment: “It takes a motorcycle fan to enjoy a motorcycle meet...few automobile men get into the heart of the unique speed fest,” the copy read.

That might be the answer, as the motorcycle declined in popularity during the 1920s and even bike fans felt the board-trackers were too far removed from what they rode.

Speed, though, had the last word. In 1922, at the Beverly Hills board-track, Jim Davis clocked 110.67 mph on a sidevalve Indian-the fastest mile motorcycle race ever-and in 1926 Curly Fredericks, again with a sidevalve Indian, turned one lap at 120.3 mph on the 1.25-mile Rockingham track.

To see the board-trackers now is to wonder how could they have done it, been that brave, hungry or foolish?

Perhaps, as the poet says, you have to have seen it not to believe it. -Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings, Rumblings

April 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRambling Roadblocks

April 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLet There Be Light

April 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2001 -

Roundup

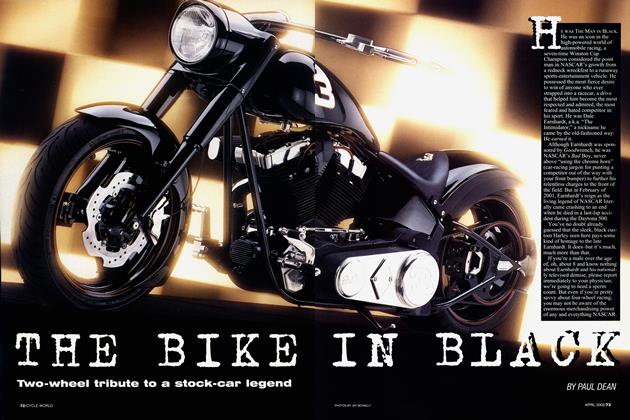

RoundupHarley's Supercruiser Revolution

April 2001 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupVoxan On Track

April 2001 By Stephan Legrand