EDITORIAL

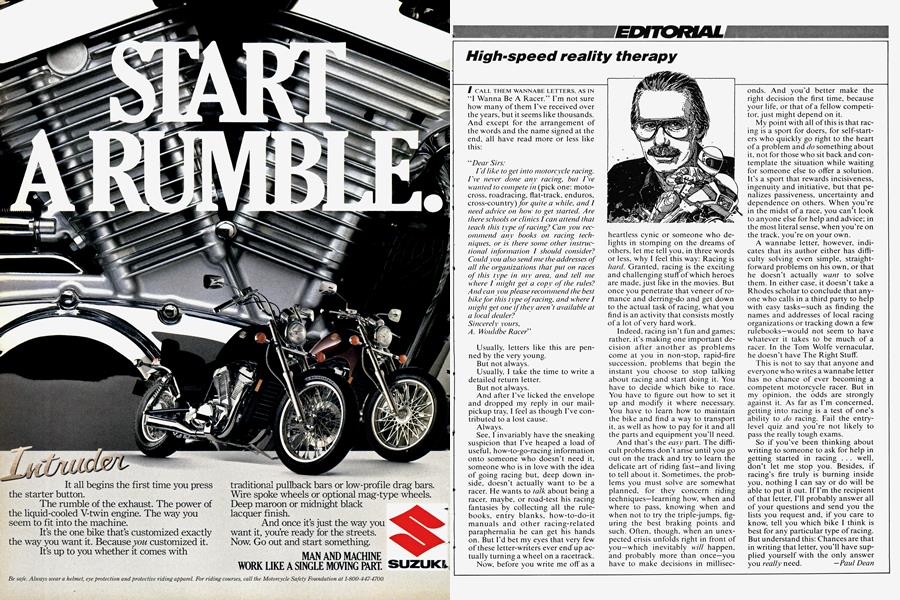

High-speed reality therapy

I CALL THEM WANNABE LETTERS, AS IN “I Wanna Be A Racer.” I’m not sure how many of them I’ve received over the years, but it seems like thousands. And except for the arrangement of the words and the name signed at the end, all have read more or less like this:

“Dear Sirs:

I'd like to get in to motorcycle racing. I've never done any racing, but I've wanted to compete in (pick one: motocross, roadracing, flat-track, enduros, cross-country) for quite a while, and I need advice on how to get started. Are there schools or clinics I can attend that teach this type of racing? Can you recommend any books on racing techniques, or is there some other instructional information I should consider? Could you also send me the addresses of all the organizations that put on races of this type in my area, and tell me where I might get a copy of the rules? And can you please recommend the best bike for this t ype of racing, and where I might get one if they aren 't available at a local dealer?

Sincerely yours, A. Wouldbe Racer ’

Usually, letters like this are penned by the very young.

But not always.

Usually, I take the time to write a detailed return letter.

But not always.

And after I’ve licked the envelope and dropped my reply in our mailpickup tray, I feel as though I’ve contributed to a lost cause.

Always.

See, I invariably have the sneaking suspicion that I’ve heaped a load of useful, how-to-go-racing information onto someone who doesn’t need it, someone who is in love with the idea of going racing but, deep down inside, doesn’t actually want to be a racer. He wants to talk about being a racer, maybe, or road-test his racing fantasies by collecting all the rulebooks, entry blanks, how-to-do-it manuals and other racing-related paraphernalia he can get his hands on. But I’d bet my eyes that very few of these letter-writers ever end'up actually turning a wheel on a racetrack.

Now, before you write me off as a heartless cynic or someone who delights in stomping on the dreams of others, let me tell you, in three words or less, why I feel this way: Racing is hard. Granted, racing is the exciting and challenging stuff of which heroes are made, just like in the movies. But once you penetrate that veneer of romance and derring-do and get down to the actual task of racing, what you find is an activity that consists mostly of a lot of very hard work.

Indeed, racing isn’t fun and games; rather, it’s making one important decision after another as problems come at you in non-stop, rapid-fire succession, problems that begin the instant you choose to stop talking about racing and start doing it. You have to decide which bike to race. You have to figure out how to set it up and modify it where necessary. You have to learn how to maintain the bike and find a way to transport it, as well as how to pay for it and all the parts and equipment you’ll need.

And that’s the easy part. The difficult problems don’t arise until you go out on the track and try to learn the delicate art of riding fast—and living to tell about it. Sometimes, the problems you must solve are somewhat planned, for they concern riding techniques—learning how, when and where to pass, knowing when and when not to try the triple-jumps, figuring the best braking points and such. Often, though, when an unexpected crisis unfolds right in front of you—which inevitably will happen, and probably more than once—you have to make decisions in millisec-

onds. And you’d better make the right decision the first time, because your life, or that of a fellow competitor, just might depend on it.

My point with all of this is that racing is a sport for doers, for self-starters who quickly go right to the heart of a problem and do something about it, not for those who sit back and contemplate the situation while waiting for someone else to offer a solution. It’s a sport that rewards incisiveness, ingenuity and initiative, but that penalizes passiveness, uncertainty and dependence on others. When you’re in the midst of a race, you can’t look to anyone else for help and advice; in the most literal sense, when you’re on the track, you’re on your own.

A wannabe letter, however, indicates that its author either has difficulty solving even simple, straightforward problems on his own, or that he doesn’t actually want to solve them. In either case, it doesn’t take a Rhodes scholar to conclude that anyone who calls in a third party to help with easy tasks—such as finding the names and addresses of local racing organizations or tracking down a few rulebooks—would not seem to have whatever it takes to be much of a racer. In the Tom Wolfe vernacular, he doesn’t have The Right Stuff.

This is not to say that anyone and everyone who writes a wannabe letter has no chance of ever becoming a competent motorcycle racer. But in my opinion, the odds are strongly against it. As far as I’m concerned, getting into racing is a test of one’s ability to do racing. Fail the entrylevel quiz and you’re not likely to pass the really tough exams.

So if you’ve been thinking about writing to someone to ask for help in getting started in racing . . . well, don’t let me stop you. Besides, if racing’s fire truly is burning inside you, nothing I can say or do will be able to put it out. If I’m the recipient of that letter, I’ll probably answer all of your questions and send you the lists you request and, if you care to know, tell you which bike I think is best for any particular type of racing. But understand this: Chances are that in writing that letter, you’ll have supplied yourself with the only answer you really need.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupSlowing the Insurance Liability Crisis

July 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

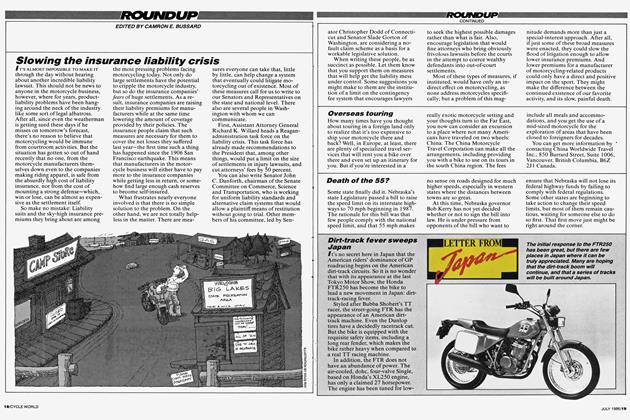

RoundupLetter From Japan

July 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

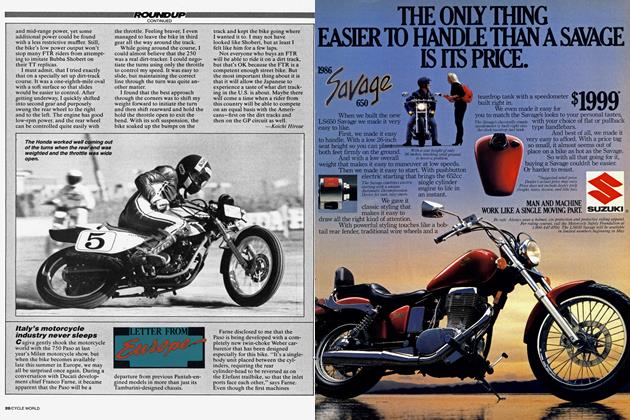

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

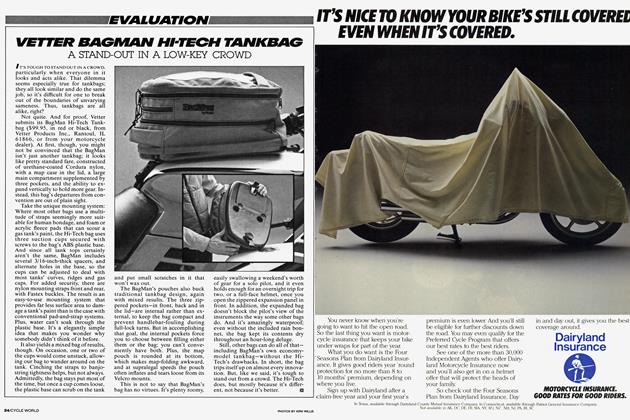

Evaluation

EvaluationVetter Flagman Hi-Tech Tankbag

July 1986 -

Features

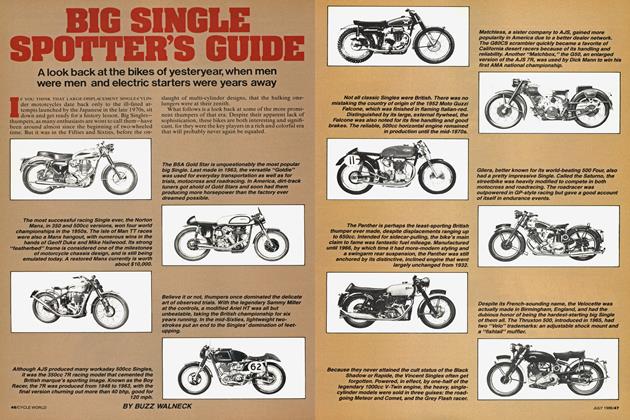

FeaturesBig Single Spotter's Guide

July 1986 By Buzz Walneck