SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Basketcase blues

Q I recently put together a basketcase Honda CBR600F2. Long story short, starting it is a bitch. When it does start, it idles okay but won’t pull until it gets above 5 grand or so. I removed the carbs, pulled the jets and the pilot screws, squirted carb cleaner and compressed air down every hole I could see and put it all back together. And, yes, I put the pilot screws in exactly the same as I found them: 2‘/2 turns out from fully seated. It runs (or doesn’t) exactly the same. What now? Mike Reid

Westerville, Ohio

Aí hate to question your enginebuilding skills, because you seem to know what you’re talking about, but are you dead-sure that you got the cam timing set correctly? There obviously is something wrong with the engine, and while several assembly errors could cause the symptoms you describe, improper cam timing is at the top of the list. Being off even one tooth on either cam with a high-revver like the F2 can cause the engine to start and run poorly.

If, however, the cam timing proves to be spot-on, there are a few other areas you should investigate. Is the cam chain new or did you reinstall the original, which could be stretched enough to throw off the timing of both cams?

Are the diaphragms in the carbs free of cracks and holes, and do they lift the slides properly when the throttles are opened? Are the valves adjusted to spec or are a few tight ones allowing some of the pressure of compression and combustion to leak past? Somewhere in all this is the reason your F2 is lazy at lower rpm, and an organized process of elimination will eventually find it.

Quarter-mile quandry

QOn the specs page you folks include with your in-depth bike reviews, you usually have the 0-30, 060, 0-100 and quarter-mile times. Just for fun, I compared the 2008 Ducati Hypermotard (December, 2007) and the 2007 Honda CBR600RR (March,

2007), and I was left with questions. Why are the quarter-mile times less than a second-and-a-half apart but the 0-100 times are 2.5 seconds apart? Also, the CBR tops out at 130 in the quarter but the Due only at 111. How is this possible? Kevin Moog

Atlanta, Georgia

A The speed of any machine during a quarter-mile run has little to do with where it is on the drag strip (except, of course, for its terminal speed at the 1320 mark). Having a bigger, torquier engine, the longer-wheelbased, 1 lOOcc V-Twin Hypermotard got a better launch than the four-cylinder, short-wheelbased 600cc Honda and its high-rpm-weighted powerband. This allowed the Ducati to be slightly farther down the strip (i.e., closer to the end) when it hit 100 mph, even though it took longer to do so. The Honda, meanwhile, after its weaker launch, gathered momentum and, being lighter and more powerful, blew past the Ducati near the end of the quarter-mile, indicated by its 19-mph higher terminal speed. As you can see by the numbers, however, the Honda took 4.3 seconds to accelerate from 100 mph to 130 at the end of the strip, whereas the Ducati did it in just 3.1 seconds but only reached 111 mph. That’s further evidence that the Due led the Honda down the earlier part of the strip.

More car vs. bike

Q Automotive differential and gearbox fluids have a service life of 50,000 miles, sparkplugs go for 100,000, and brake fluid in a highheat environment never gets changed. On a motorcycle, these things are supposed to be replaced in 10,000 to 15,000 miles or less. What is the reason for such a huge difference?

Jim Blair Palatine, Illinois

A There are many reasons, and one way or another, most are based on the fact that a motorcycle is not a car. The majority of bikes, for example, share engine oil with the transmission, clutch and primary drive; this introduces into the oil a greater quantity of contaminants involving types of material (metal gear shavings and worn-off clutch-plate fiber, mostly) that a car engine either sees much less of or not at all. So while the transmission may safely be able to go many more thousands of miles on the same oil, the power-producing part of the engine unit cannot. Other motorcycles, such as HarleyDavidsons, do use separate engine, transmission and primary-drive oil; but like all motorcycles, their gearboxes are of a different design (geardog rather than synchromesh) that does not call for the heavier, EP (extreme pressure) lubricants used in automotive standard transmissions. And due to the small amount of lubricant in the ultra-compact final drives of most shaft-drive motorcycles, the oil should be changed more frequently than that in the differential of a car.

Motorcycles also generally have higher-revving, higher-performance engines than cars, most often with significantly higher compression ratios, and those factors tend to place greater demands on their sparkplugs. A highmileage plug that can still fire consistently in a 9:1 engine that never exceeds 6000 or 6500 rpm very well might not fire at all in an 11.5:1 bike motor spinning at 10,000 to 15,000 rpm.

And brake fluid in an automobile never gets changed? Au contraire. Brake fluid is hygroscopic, which means it absorbs moisture from the air, and moisture in the system can cause brakes to be mushy, inconsistent and even fail altogether. Most car manufacturers therefore recommend changing brake fluid at regular intervals. Some suggest every 25,000 to 50,000 miles, others advocate every two or three years. Motorcycle braking systems are smaller and have far less fluid capacity, which is why bike-makers recommend changing the fluid more frequently.

Shaken, not broken

QWhy do so many aftermarket exhaust systems and slip-ons use springs to hold the pipes or mufflers on instead of some sort of clamp? Jim Clausen

Posted on www.cycleworld.com

Alt helps the pipes survive the effects of vibration. Exhaust systems are subject not only to vibration produced by the reciprocating and rotating masses inside the engine, they also must endure powerful vibrations caused by the sound waves resonating through them. Many other components on motorcycles routinely are rubbermounted (headlight, taillight, turnsignals, instruments, fuel tank, to name just a few) to isolate them from vibration, but the joints between muffler and header, as well as between header and exhaust port, reach temperatures that can fry rubber. So springs are often used to allow those components to “float” slightly. This doesn’t completely isolate them from vibration but does help them endure it. The temperatures near the outlets of exhaust systems are much lower, so mufflers usually are

rubber-mounted where they attach to the frame.

Years ago, when most motorcycle exhaust systems were rigidly mounted, cracked and broken header pipes, mufflers and mounting brackets were commonplace. Designers eventually learned that attaching those components-and many others-more loosely all but eliminated those kinds of failures.

Bridging the gap

QI just bought a 1985 Kawasaki GPz900, and when I picked up the bike, the previous owner gave me the factory shop manual. I was browsing through the manual and saw that the rings on the piston are supposed to have an end gap of between 0.2 and 0.35mm. I am not a mechanic and don’t know much about engines, but I am curious as to why the rings would have any end gap at all. I do know that the rings are supposed to seal the pistons in the cylinder, so why would they have a gap that could leak? Frank Aguirre

Posted on America Online

A Because heat causes expansion. Like just about everything else, piston rings expand as they get hotter; and since rings are subjected to the tremendous heat of combustion, they undergo significant expansion. If the rings were installed with their ends butted against each other without any gap, they would try to expand to a diameter larger than the cylinder itself, causing them to bind and distort. The pressure they’d then exert on the cylinder walls would push through the boundary layer of oil on the walls, causing scoring, damage to the ring lands (the grooves the rings fit into in the pistons) and possibly even seizure. But with an adequate end gap, the rings can expand without any such problems.

Typically, each piston in a four-stroke engine has three rings: a compression (top) ring, a secondary compression ring and an oil-control ring, which might consist of three separate pieces. To minimize the amount of compression or combustion pressure that might escape through the gaps in the rings, the gaps need to be spaced evenly around each cylinder. The gap in the second ring should be located about 120 degrees away from the top ring’s, and the gap in the oil-control ring should be positioned 120 degrees from the other two.

A general rule-of-thumb for ring end gap is between .003 to .007 inch for every inch of piston diameter. The requirement varies depending upon numerous other factors, including whether the engine is normally aspirated or turbo/supercharged, burns gasoline or other fuel, is intended for street use or racing, and which ring (top, second or oil-control) is in question.

The pie thing again

QYOU still owe an apology to Jeff Cottrell, whose December-issue letter (“Patches and pies”) dealt with the effect of contact-patch areas put down by tires of different widths and diameters.

You said that wider or taller tires would produce greater contact-patch area, but the principles of buoyancy, established centuries ago by Archimedes and others, disagree. The area required to support any given weight is determined by dividing the weight by the pressure. So if the rear of a motorcycle with rider weighed 300 pounds and the rear tire was inflated to 30 psi, that tire’s contact patch area would be 10 square inches (300-K30=10). A wider tire would likely produce a wider contact patch, but it also would be shorter and have the same area. Likewise, a taller tire would have a longer patch but it would be shorter, and have the same area.

Looks like you may have to order up a big slice of humble pie after all.

Carl Harmon Wichita Falls, Texas

Ain theory, you are absolutely correct. And if tires were simply balloons, the contact patch of any one of them would indeed have the same area when loaded with the same weight and inflated to the same pressure. But a tire is not a balloon. It is a complex structure of cords and belts and stiffeners covered in rubber and mounted on a circular frame. When inflated or weighted, it does not necessarily expand evenly throughout, and its rubber stretches or compresses according to the properties of elasticity, not by the rules of buoyancy.

Here’s an experiment I’ve performed several times: Place a motorcycle on a smooth, even surface, lift up its rear end, slide a piece of light-colored construction paper under the rear, put any kind of marking material (grease, ink, paint) on a segment of the rear tire’s tread, then lower the bike down with its full weight on the tires and the marked part of the rear tire on the paper. Now lift the rear of the bike back up again, and what is left on the paper is a footprint of the tire’s contact patch. If you continue to follow this procedure with wider (and even narrower) tires mounted on different-width wheels but with identical air pressures, you usually will observe differences in contact-patch area. Of course, those differences are never in proportion to the variations in tire widths-that is, a 33-percent wider tire does not produce a 33percent larger contact patch. In fact, any differences are rather small. But in most cases, there are differences-in area, not just in shape. After all, there are reasons-besides fashion-tire manufacturers make wider tires, and why bike manufacturers put them on their larger and more-powerful motorcycles.

In retrospect, however, I must admit

that I was too assertive when responding to Mr. Cottrell, and in doing so, I overstated my case. My apologies to him and to the numerous other readers who have contacted me regarding this issue of buoyancy. I’ll be glad to chow down on the pie of their choice, humble or otherwise. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology?

Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651 ; 3) email it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

Feedback Loop

Ql Service read with letter interest abouta Sherri 1985 Seeger’s Honda V30 Magna (“Watts the problem?” November, 2008) that intermittently shuts off entirely and then will restart again after a short time. I recently encountered similar symptoms with a 1982 Honda CB750 Custom, and the problem was a cracked main fuse. Occasionally, the bike would run poorly or stop, with no electrical power anywhere, and then just as suddenly would regain its electrics and run normally. The 26-year-old fuse element was brittle and had cracked nearly invisibly, causing the intermittent shutoff. I noticed a blue spark in the fuse while troubleshooting the problem after the bike had stalled. So, check and replace those old Honda main fuses!

Bill Hottinger Silverdaie, Washington

A Terrific tip, Bill. That’s a circumstance that could have even a highly skilled mechanic running in circles. A cracked fuse might not be the cause of Seeger’s problem, but it certainly is a possibility well worth pursuing. Thank you very much.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

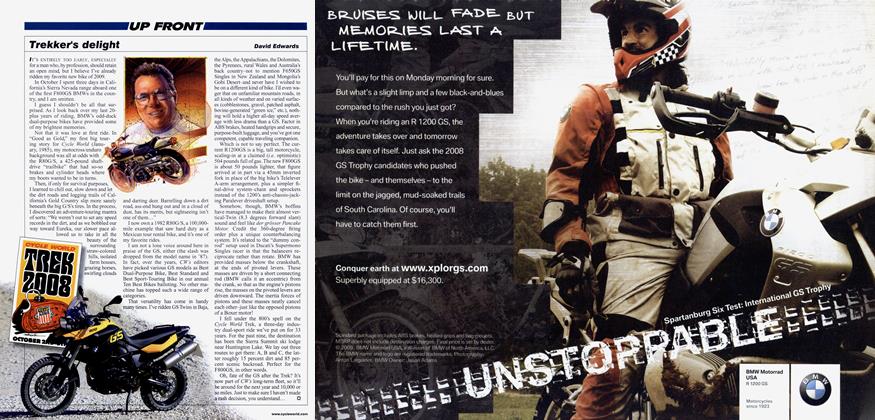

Up FrontTrekker's Delight

February 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsArt And the Motorcycle Museum

February 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInvisible Speed

February 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Giro Heroes

Giro HeroesHotshots

February 2009 -

Departments

DepartmentsNew Ideas

February 2009 -

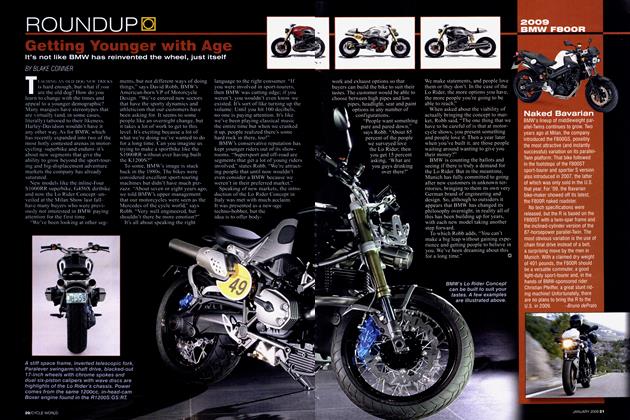

Roundup

RoundupGetting Younger With Age

February 2009 By Blake Conner