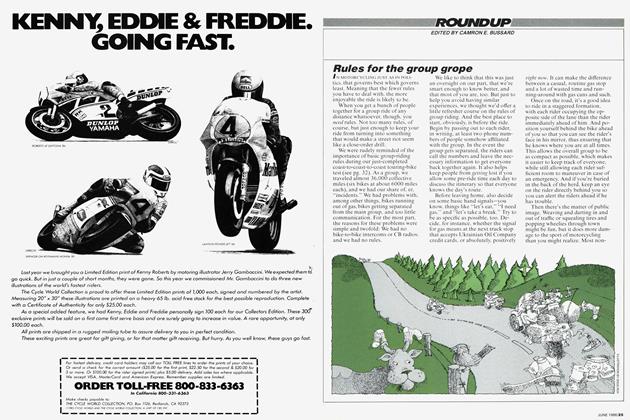

My First Daytona

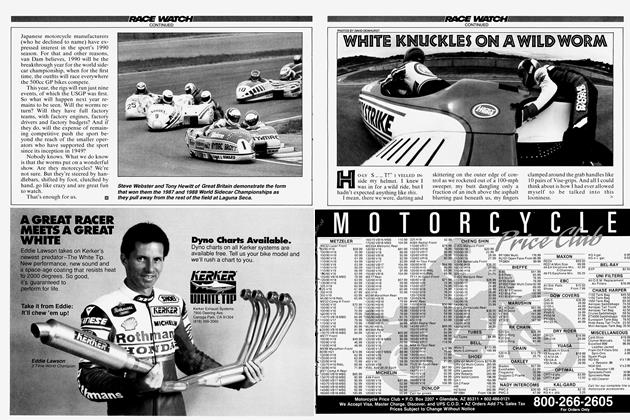

RACE WATCH

Daytona '86

A California club-racer takes his shot at the big time

Doug Toland is familiar to Cycle World readers, in image if not in name. Toland helps out with our road testing and is often seen blazing his way, photographically, across the magazine's pages. Toland is a good roadracer, as well, good enough to set class records at local racetracks and finish fifth at last year's Laguna Seca Superbike national. This year, Toland has hooked up with the Vance & Hines roadrace team to ride their GSX-R 750 Suzuki at selected nationals. Daytona was the team's debut race, as well as the 23year-old Toland's very first time at the world-famous Florida track.

DURING THE 44-HOUR, NONstop truck ride across the country, I’d had a lot of time to think about Daytona. Still, I didn’t know quite what to expect when my crew pushed me off for the first practice session.

Racetracks are very strange places; they can either be intimidating or fun. Daytona is fun. After a few familiarization laps, I started to get used to the banking. From the pits, it doesn’t look that steep, but try to ride on it at anything less than full throttle and the the 31-degree tilt drives you to the inside of the track where it is flat. Then there’s the problem of not knowing quite where to look, because riding at that much of an angle, with a cement wall flashing by three feet away, is very disconcerting, to say the least. Two or three times around, though, and it all falls into place.

After coming off the banking and powering up to 160 mph or more on the back straight, you have to deal with the chicane. You really have to use the brakes hard to slow down to 60 or 70 mph before making the quick left-right-left maneuver. Then it’s time for another top-speed run on the south banking, which leads to the front straight and Turn One, where you have to haul the bike down to 50 or 60 mph before peeling off to tackle the five-corner infield section.

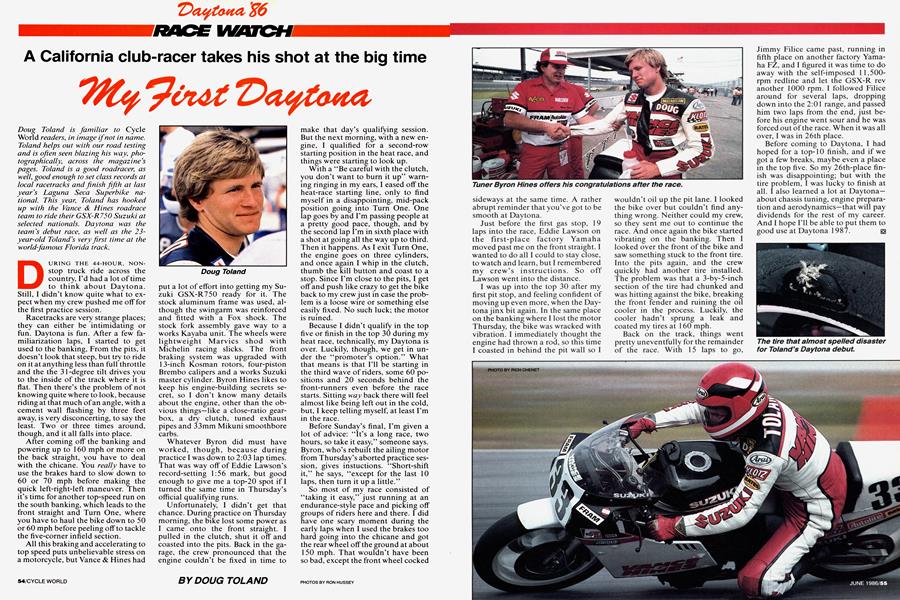

All this braking and accelerating to top speed puts unbelievable stress on a motorcycle, but Vance & Hines had put a lot of effort into getting my Suzuki GSX-R750 ready for it. The stock aluminum frame was used, although the swingarm was reinforced and fitted with a Fox shock. The stock fork assembly gave way to a works Kayaba unit. The wheels were lightweight Marvics shod with Michelin racing slicks. The front braking system was upgraded with 13-inch Kosman rotors, four-piston Brembo calipers and a works Suzuki master cylinder. Byron Hines likes to keep his engine-building secrets secret, so I don’t know many details about the engine, other than the obvious things—like a close-ratio gearbox, a dry clutch, tuned exhaust pipes and 33mm Mikuni smoothbore carbs.

Whatever Byron did must have worked, though, because during practice I was down to 2:03 lap times. That was way off of Eddie Lawson’s record-setting 1:56 mark, but good enough to give me a top-20 spot if I turned the same time in Thursday’s official qualifying runs.

Unfortunately, I didn’t get that chance. During practice on Thursday morning, the bike lost some power as I came onto the front straight. I pulled in the clutch, shut it off and coasted into the pits. Back in the garage, the crew pronounced that the engine couldn’t be fixed in time to make that day’s qualifying session. But the next morning, with a new engine, I qualified for a second-row starting position in the heat race, and things were starting to look up.

With a “Be careful with the clutch, you don’t want to burn it up” warning ringing in my ears, I eased off the heat-race starting line, only to find myself in a disappointing, mid-pack position going into Turn One. One lap goes by and I’m passing people at a pretty good pace, though, and by the second lap I’m in sixth place with a shot at going all the way up to third. Then it happens. As I exit Turn One, the engine goes on three cylinders, and once again I whip in the clutch, thumb the kill button and coast to a stop. Since I’m close to the pits, I get off and push like crazy to get the bike back to my crew just in case the problem is a loose wire or something else easily fixed. No such luck; the motor is ruined.

Because I didn’t qualify in the top five or finish in the top 30 during my heat race, technically, my Daytona is over. Luckily, though, we get in under the “promoter’s option.” What that means is that I’ll be starting in the third wave of riders, some 60 positions and 20 seconds behind the front-runners even before the race starts. Sitting way back there will feel almost like being left out in the cold, but, I keep telling myself, at least I’m in the race.

Before Sunday’s final, I’m given a lot of advice: “It’s a long race, two hours, so take it easy,” someone says. Byron, who’s rebuilt the ailing motor from Thursday’s aborted practice session, gives instuctions. “Short-shift it,” he says, “except for the last 10 laps, then turn it up a little.”

So most of my race consisted of “taking it easy,” just running at an endurance-style pace and picking off groups of riders here and there. I did have one scary moment during the early laps when I used the brakes too hard going into the chicane and got the rear wheel off the ground at about 150 mph. That wouldn’t have been so bad, except the front wheel cocked sideways at the same time. A rather abrupt reminder that you’ve got to be smooth at Daytona.

DOUG TOLAND

Just before the first gas stop, 19 laps into the race, Eddie Lawson on the first-place factory Yamaha moved past me on the front straight. I wanted to do all I could to stay close, to watch and learn, but I remembered my crew’s instructions. So off Lawson went into the distance.

I was up into the top 30 after my first pit stop, and feeling confident of moving up even more, when the Daytona jinx bit again. In the same place on the banking where I lost the motor Thursday, the bike was wracked with vibration. I immediately thought the engine had thrown a rod, so this time I coasted in behind the pit wall so I wouldn’t oil up the pit lane. I looked the bike over but couldn’t find anything wrong. Neither could my crew, so they sent me out to continue the race. And once again the bike started vibrating on the banking. Then I looked over the front of the bike and saw something stuck to the front tire. Into the pits again, and the crew quickly had another tire installed. The problem was that a 3-by-5-inch section of the tire had chunked and was hitting against the bike, breaking the front fender and ruining the oil cooler in the process. Luckily, the cooler hadn’t sprung a leak and coated my tires at 160 mph.

Back on the track, things went pretty uneventfully for the remainder of the race. With 15 laps to go, Jimmy Filice came past, running in fifth place on another factory Yamaha FZ, and I figured it was time to do away with the self-imposed 11,500rpm redline and let the GSX-R rev another 1000 rpm. I followed Filice around for several laps, dropping down into the 2:01 range, and passed him two laps from the end, just before his engine went sour and he was forced out of the race. When it was all over, I was in 26th place.

Before coming to Daytona, I had hoped for a top-10 finish, and if we got a few breaks, maybe even a place in the top five. So my 26th-place finish was disappointing; but with the tire problem, I was lucky to finish at all. I also learned a lot at Daytona— about chassis tuning, engine preparation and aerodynamics—that will pay dividends for the rest of my career. And I hope I’ll be able to put them to good use at Daytona 1987. o

View Full Issue

View Full Issue