ASK THE MAN WHO OWNS ONE (AND BUILT TWO)

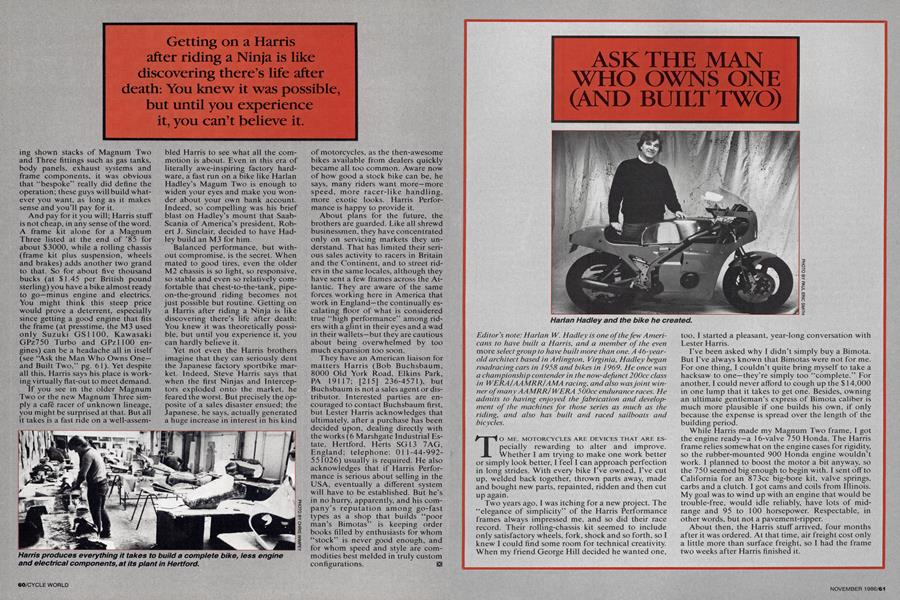

Editor's note: Harlan W. Hadley is one of the few Americans to have built a Harris, and a member of the even more select group to have built more than one. A 46-year -old architect based in Arlington, Virginia, Hadley began roadracing cars in 1958 and bikes in 1969. He once was a championship contender in the now-defunct 200cc class in WERA/AAMRR/AMA racing, and also was joint winner of many AAMRR/ WERA 500cc endurance races. He admits to having enjoyed the fabrication and development of the machines for those series as much as the riding, and also has built and raced sailboats and bicycles.

TO ME, MOTORCYCLES ARE DEVICES THAT ARE ESpecially rewarding to alter and improve. Whether I am trying to make one work better or simply look better, I feel I can approach perfection in long strides. With every bike I've owned, I've cut up, welded back together, thrown parts away, made and bought new parts, repainted, ridden and then cut up again.

Two years ago, I was itching for a new project. The “elegance of simplicity’’ of the Harris Performance frames always impressed me, and so did their race record. Their rolling-chassis kit seemed to include only satisfactory wheels, fork, shock and so forth, so I knew I could find some room for technical creativity. When my friend George Hill decided he wanted one,

too, I started a pleasant, year-long conversation with Lester Harris.

I’ve been asked why I didn’t simply buy a Bimota. But I’ve always known that Bimotas were not for me. For one thing, I couldn’t quite bring myself to take a hacksaw to one—they’re simply too “complete.’’ For another, I could never afford to cough up the $ 14,000 in one lump that it takes to get one. Besides, owning an ultimate gentleman’s express of Bimota caliber is much more plausible if one builds his own, if only because the expense is spread over the length of the building period.

While Harris made my Magnum Two frame, I got the engine ready—a 16-valve 750 Honda. The Harris frame relies somewhat on the engine cases for rigidity, so the rubber-mounted 900 Honda engine wouldn’t work. I planned to boost the motor a bit anyway, so the 750 seemed big enough to begin with. I sent off to California for an 873cc big-bore kit, valve springs, carbs and a clutch. I got cams and coils from Illinois. My goal was to wind up with an engine that would be trouble-free, would idle reliably, have lots of midrange and 95 to 100 horsepower. Respectable, in other words, but not a pavement-ripper.

About then, the Harris stuff arrived, four months after it was ordered. At that time, air freight cost only a little more than surface freight, so I had the frame two weeks after Harris finished it.

íí My Harris is a different kind of motorcycle. It weighs 400 pounds and is incredibly responsive. I will probably own this machine until I’m senile!’

What a grand moment at the air-freight terminal building, pulling open the wood and cardboard packing cases under the watchful glare of the Customs officers. They were looking for drugs while I was salivating over the hardware: beautiful hand-brazed joints on Reynolds 531 tubing, big needle-bearing swingarm-pivot bearings with an integral ball-thrust bearing, very nice rough-cast aluminum tripleclamps, a hand-formed aluminum gas tank with a huge American aircraft-style filler cap, and a White Power rear suspension unit with remote reservoir.

Later, at home, I was pleased to find a number of things I could improve on, such as engine-mounting plates, rear-brake master cylinder location and linkage, shift lever linkage, and all the fiberglass parts. It was clear that Harris Performance had intended the bike to be a Formula One or endurance roadracer; the fixtures they had included for street-riding accessories were minimal. But I wanted a Formula One bike with great lights, loud horns, a radar detector, a proper fuse box and a tool storage box large enough for two splits of champagne.

My workshop is small. I have no machine tools— unless you’d call my Taiwanese bench-model drill press such. I have a small torch, a sturdy vise, a hacksaw, dial calipers and hundreds of common hand tools. The only fabrication for this project I was not equipped to perform myself was the cylinder boring, the heliarc welding, the anodizing of aluminum parts and the painting.

While the frame was off being painted, I did dozens of freehand design drawings of the various additions and alterations. Having a clear understanding of what you want to do is probably the most often overlooked—and most vital—part of any project.

When I got the frame back, I carefully assembled it up onto its wheels and tires and slipped the engine into place. Everything fit perfectly. There was none of the sort of production slop-fit we’re used to in even the best stock bikes. If this was a “poor man’s” Bimota, it was built to a rich man’s exacting tolerances.

The fiberglass seat, fairing and fender were then trimmed and modified, filled and patched, sanded and primed until my patience was exhausted. They didn’t need this work, for they fit very well as delivered; I just wanted to sharpen the aesthetics and build the tool storage box into the seat. I added Dzus fasteners for easy fairing removal, then my friend Patrick Bodden painted the whole works Revlon Red.

I then fabricated all the steel and aluminum bolt-on

parts. These included footpeg plates, brake and shift levers, rear brake stay, caliper mounting plates, instrument mounts, idiot-light box and more linkages. First I drew everything, then made mock-ups. I find I rarely get anything right the first time, and this technique lets my worst blunders be only in cardboard. I wanted the aluminum bits to be a nonstandard gray, so I had them all done at the same time to assure a color match. And the only other hand metalwork was the resectioning of two header pipes to clear the fairing.

The motorcycle was designed by Harris to be so compact that the battery and other electrical components cannot be located in the same places they occupy in the stock Honda. This and the fact that I wanted to add and change several things meant that I had to make the wiring harness from scratch. So I cut up a Honda harness to get the color-coded wire, and used Honda wiring terminals exclusively. I then encased the whole thing in Teflon heat-shrink tubing. I built a fiber-optics cable into the harness to let me know at the instruments that my tail and brake lights are working. I put the headlights and horns on relays, and used Honda V-65 instruments because they’re compact and have a 165-mph speedometer. In fact, I used as many stock Honda parts as possible to simplify long-term maintenance.

When all this was done, I turned the key and started it up. I fiddled with carb synchronization for about an hour, filling the house with delicious exhaust fumes. The engine sounded great and everything worked as I took a little landmark ride around the neighborhood. Eventually, the State of Virginia perused all my receipts and sent a gentleman around to give the project its blessing in the form of a numbered plate on the steering head. He had restored a couple of Corvettes and seemed to appreciate the project.

So did I, and I continue to. I ride the latest stock sportbikes as they come out, and am always pleased by how much they improve. But my Harris is a different kind of motorcycle, it weighs 400 pounds with oil, and is incredibly responsive. Its thresholds are so high I always feel a margin of extra capability. The bike will happily tolerate legal speeds, even in town, and is, surprisingly, quite comfortable.

I will probably own this machine until I’m senile. Building and owning a bike like the Harris is the best way I know to escape the bike-of-the-month lust that is so infectuous these days. One does not lose interest in a machine built with one’s own hands, particularly when the machine is as thrilling a performer as is this Harris Honda.

Harlan W. Hadley

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

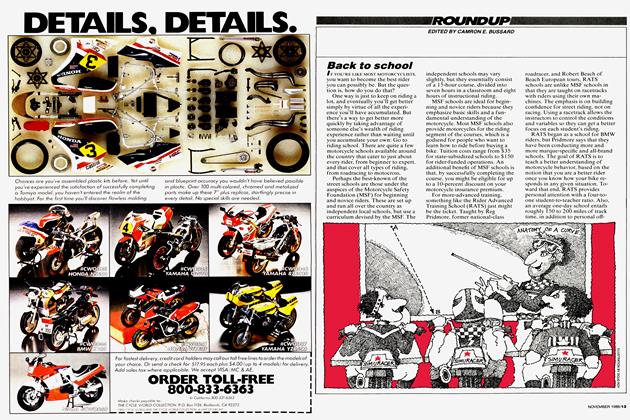

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

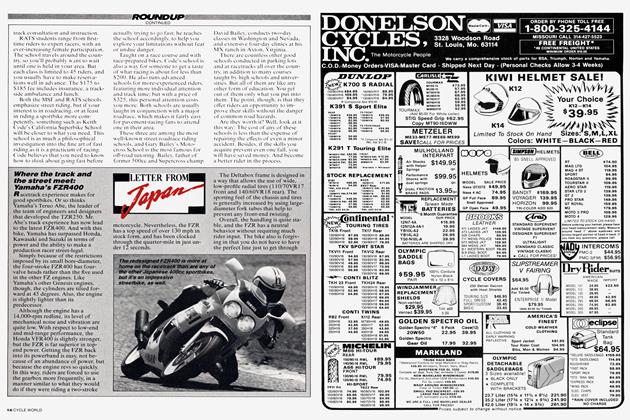

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart