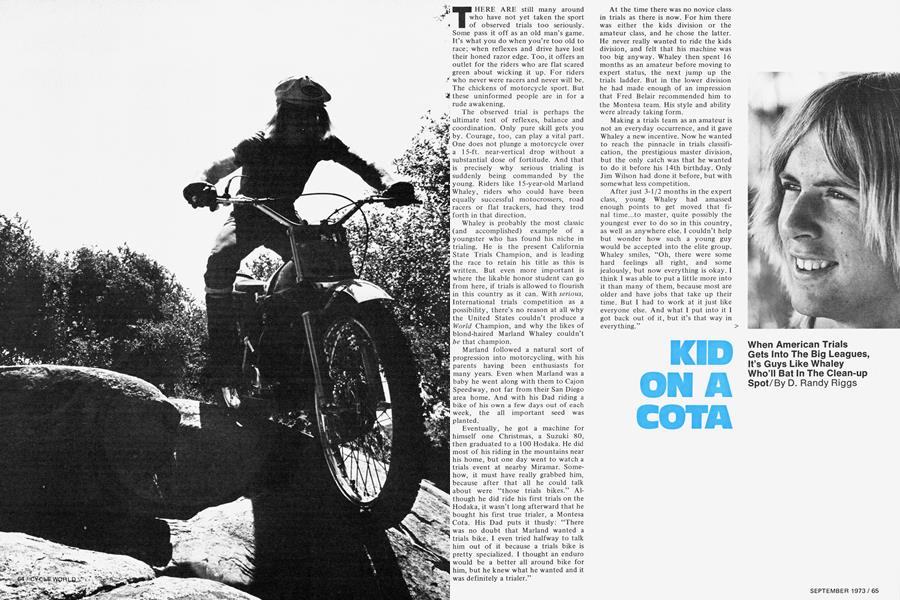

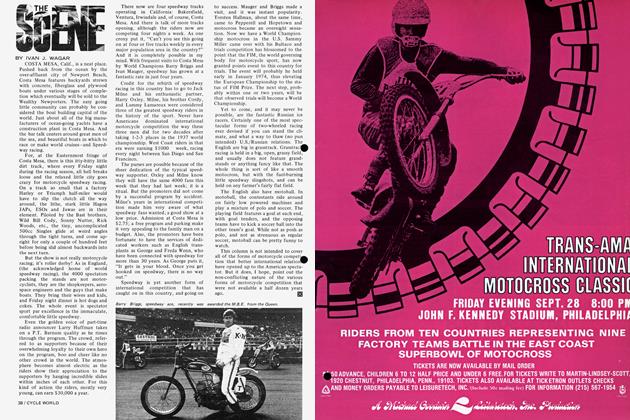

KID ON A COTA

THERE ARE still many around who have not yet taken the sport of observed trials too seriously. Some pass it off as an old man's game. It's what you do when you're too old to race; when reflexes and drive have lost their honed razor edge. Too, it offers an outlet for the riders who are flat scared green about wicking it up. For riders who never were racers and never will be. The chickens of motorcycle sport. But these uninformed people are in for a rude awakening.

The observed trial is perhaps the ultimate test of reflexes, balance and coordination. Only pure skill gets you by. Courage, too, can play a vital part. One does not plunge a motorcycle over a 15-ft. near-vertical drop without a substantial dose of fortitude. And that is precisely why serious trialing is suddenly being commanded by the young. Riders like 15-year-old Marland Whaley, riders who could have been equally successful motocrossers, road racers or flat trackers, had they trod forth in that direction.

Whaley is probably the most classic (and accomplished) example of a youngster who has found his niche in trialing. He is the present California State Trials Champion, and is leading the race to retain his title as this is written. But even more important is where the likable honor student can go from here, if trials is allowed to flourish in this country as it can. With serious, International trials competition as a possibility, there's no reason at all why the United States couldn't produce a World Champion, and why the likes of blond-haired Marland Whaley couldn't be that champion.

Marland followed a natural sort of progression into motorcycling, with his parents having been enthusiasts for many years. Even when Marland was a baby he went along with them to Cajon Speedway, not far from their San Diego area home. And with his Dad riding a bike of his own a few days out of each week, the all important seed was planted.

Eventually, he got a machine for himself one Christmas, a Suzuki 80, then graduated to a 100 Hodaka. He did most of his riding in the mountains near his home, but one day went to watch a trials event at nearby Miramar. Somehow, it must have really grabbed him, because after that all he could talk about were "those trials bikes." Although he did ride his first trials on the Hodaka, it wasn't long afterward that he bought his first true trialer, a Montesa Cota. His Dad puts it thusly: "There was no doubt that Marland wanted a trials bike. I even tried halfway to talk him out of it because a trials bike is pretty specialized. I thought an enduro would be a better all around bike for him, but he knew what he wanted and it was definitely a trialer."

At the time there was no novice class in trials as there is now. For him there was either the kids division or the amateur class, and he chose the latter. He never really wanted to ride the kids division, and felt that his machine was too big anyway. Whaley then spent 16 months as an amateur before moving to expert status, the next jump up the trials ladder. But in the lower division he had made enough of an impression that Fred Belair recommended him to the Montesa team. His style and ability were already taking form.

Making a trials team as an amateur is not an everyday occurrence, and it gave Whaley a new incentive. Now he wanted to reach the pinnacle in trials classification, the prestigious master division, but the only catch was that he wanted to do it before his 14th birthday. Only Jim Wilson had done it before, but with somewhat less competition.

After just 3-1/2 months in the expert class, young Whaley had amassed enough points to get moved that final time...to master, quite possibly the youngest ever to do so in this country, as well as anywhere else. I couldn't help but wonder how such a young guy would be accepted into the elite group. Whaley smiles, "Oh, there were some hard feelings all right, and some jealously, but now everything is okay. I think I was able to put a little more into it than many of them, because most are older and have jobs that take up their time. But I had to work at it just like everyone else. And what I put into it I got back out of it, but it's that way in everything." >

When American Trials Gets Into The Big Leagues, It's Guys Like Whaley Who'll Bat In The Clean-up Spot

D. Randy Riggs

Marland was quick to point out, however, that many trials riders he's seen move up the ladder in quick succession have faded from the scene equally as fast. "The ones that seem to hang on the most are the ones that are slow learners and keep trying and trying." Whaley is the obvious exception.

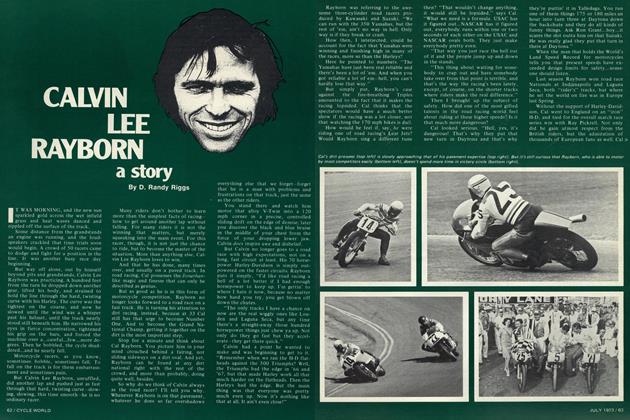

Like many of the top trials riders, Whaley is big (6 ft., 155 lb.) and he's strong. And make no mistake about it, Marland makes good use of the leverage that bulk can provide. His riding is calculated when he's trying hard, and watching him in any sort of section is a treat.

Just where does the phenomenal ability and balance come from? When I interjected that much of it might be born in him, he disagreed. "Putting your mind to it and practicing is everything. You have to stay in good physical shape and watch your diet." True. But no one can stand there and watch him attack a section and say that he has no natural ability. When Whaley gets serious...look out.

What is it that he needs to get better, to be as good as the Europeans? "Experience, but not all of it in Southern California. The one thing that does me the most good is traveling. I always learn something every time Em away." Marland has been to a few of the Western states, and to Northern California in much of the traveling he's done. But he earned a trip to Spain this year as well, and competed in one event that showed him more about trialing than an entire season in Southern California. The St. Llorenc del Munt in Tarrasa was a toughie, and Marland finished 55th out of 120, many of whom didn't even complete the event. It was officially the 3rd round of the European Championship, and apparently a much different event than we find in this country.

Many will agree with Marland when he says that our top riders should spend a full year in Europe gaining experience. "It's the only way we'll ever be able to compete on a serious basis with those guys. Riding the same terrain week in and week out over here just doesn't get it. We could learn so much just by running one season over there."

Marland rates Northern Californian Lane Leavitt as probably America's top trialer. "You can't give away too much and beat him, because generally he's on the stick. But I don't think he's any natural or anything like that...he's just been around the country and had so much experience."

Probably one of the things keeping trials from becoming really big in this country is the clannish, club type atmosphere that surrounds most of the events. Many beginners are apt to be put off by such organization, especially when they are charged entry fees as high as $12, simply because they are not ATA (American Trials Assn.) members. And to make matters worse, they must first join a club before they can join the ATA. And it's like this in many areas of the country.

Whaley feels that it was necessary to start out this way in the beginning, when trials was just getting a foothold in this country. "It was a matter of survival. But now it's different, especially with the Japanese getting into the act. The trouble is that all the various organizations like the ATA and PITS (Pacific International Trials Society) and what have you, are going against one another, instead of pulling together. They're not running under universal enough rules for one thing, everywhere you go it's different."

Marland gets into a section much the same as most riders, giving it a careful look the first time around. But he seems to have an excellent memory and spends only a few quick moments on later loops. He has an incredible sense of precisely where he wants his front wheel, and perfect throttle control assures its placement. His rhythm in any type of section is nothing short of fantastic.

Whaley is emphatic about always riding the same machine, whether practicing or otherwise. He rides only trials, and attacks practice sections over and over until they're cleaned. Too, these sections are usually most difficult.

Machinery preparation is another area he gloats over. And one look at his immaculate Cota shows the attention he gives it. Basically a standard 247 model, it features little touches that make it better suited to his riding characteristics. When you admire its beauty, you can tell he is pleased.

Whaley would be the type of rider the United States could be proud to send abroad in International competition. When the ATA wakes up, and trials becomes "big time," we can expect to see the name Marland Whaley at the top of the finishing lists. For, a potential World Champion he is... wouldn't it be a shame if we let him go to waste? ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue