EDITORIAL

Who was that masked man?

IF THE LONE RANGER WERE AROUND today, you absolutely, positively know that he’d ride a motorcycle. It would probably be big and most likely would be white, but it definitely would be a motorcycle, not a horse. It’s tough these days to crusade against crime and injustice on a horse; and I just can’t picture the Lone Ranger riding off into the sunset shouting a hearty “Hi-yo, Silver” out the window of a ... a Buick.

Nope. A motorcycle, to be sure.

Now, you might be thinking that you’ve heard this line of reasoning before, about how a motorcycle is the motorized equivalent of a horse, and that its rider is simply a modern-day cowboy. But my intention here is not to talk about that cowboy-reincarnated cliché, but rather to point out something that many of you may not have thought about before: that motorcycles tend to make Lone Rangers out of the people who ride them.

Indeed, by its very design, a motorcycle makes it hard for its rider not to be alone. For one thing, the maximum number of people you can cram onto one bike (legally, at least) is two. And although those two do sit quite close to one another, the amount and type of camaraderie they can have aboard a moving motorcycle is quite limited. They might enjoy simply being near each other, but when it comes to being amused while rolling down the road, each of them is all but alone.

Matter of fact, intelligent dialogue of any sort is practically impossible on a moving bike. The tandem seating arrangement means you can’t talk face-to-face, which in itself seriously compromises the quality of conversation. On top of that, the wind roar, engine racket and ambient noise generally limit on-bike communication to hand signals and short questions that you usually have to yell at the top of your lungs, and that require only a nod of the head in reply. (“Are you hungry yet?” “Did you see what that couple in the station wagon was doing?”) Intercom systems can help somewhat, but they’re not always possible or practical, and still aren't suitable for real conversations.

So in many important ways, you’re always alone on a motorcycle, even when there is someone else on it with you. The same goes for riding in a group: As long as you’re in motion,

you're effectively alone.

But I don’t consider that a disadvantage. To the contrary, it’s one of the things I like most about traveling by bike with other people: You can be alone and be with someone at the same time.

That's important to me, because the time I spend on a motorcycle is often my most productive, especially during long rides. I’m able to think with exceptional clarity and logic while riding, so I use those occasions for reflection, for ironing the wrinkles out of new ideas and working the kinks out of old problems. It’s a chance for me to “get in touch with myself,” as the self-help trendies would put it. I do that best when I'm alone, when I can hoard my own thoughts without having them interrupted by those of others.

Which is not to say that I’m antisocial. for just the opposite is the case: I truly enjoy the company of others when I travel. And I’ve found that although riding a motorcycle greatly diminishes the quantity of social intercourse, it vastly improves its qualit y.

It’s easy to see why. Travel by automobile forces the occupants into non-stop interaction practically all of the time the vehicle is moving, and much of the time it isn’t. So no matter if it’s just you and your main squeeze traveling in a sportscar, or you, your wife, your four kids and your motherin-law in a Winnebago, you're in each other’s faces almost non-stop, for days, maybe weeks, on end. Even meal breaks and the like don’t provide much relief, for they’re little more than an out-of-car continuation of what was going on in the car. If

that’s not a formula for growing really weary of one another, I don’t know what is.

But group travel by motorcycle tends not to cause such problems. You converse with your fellow travelers only when you stop for some reason—to eat, to gas up, to sightsee, to rest or to sleep. That alone tends to make group travel less trying for all involved, as well as fueling much more-interesting dialogue. Rather than babbling on and on mindlessly in forced conversation as the miles roll past—which is what usually happens amongst the occupants of a car after a few hours—you have to save your thoughts on a motorcycle, and hold them until you stop.

This helps turn meal breaks and all other kinds of stops into real social events. Individually, you, your fellow riders and any passengers store up things to chat about while you’re out on the road, and that can’t help but lead to more lively and intelligent conversation once you stop. You have time to think about what you want to say and how you want to say it, rather than simply blurting out whatever happens to come to mind while you’re driving along.

Not only that, a group of motorcyclists—say, four riders on four different bikes—encounters more fodder for discussion than an equal number of people all riding in the same car. Each rider tends to have different observations along the way, providing more different subjects to broach at break time. And even when individual riders all see exactly the same things, each has time to mull over what those observations mean to him or her, and how best to express them—or, in some cases, to exaggerate them—at the next stop.

As you can see, then, a bit of aloneness can help make group travel much more enjoyable. This Lone Ranger syndrome also might help explain why touring riders you meet out on the road generally seem so downright friendly: They like themselves, enough so, at least, that they aren’t afraid to spend a lot of time on their bikes—alone. That’s also the probable reason why people who aren’t happy with themselves tend to avoid long-distance riding: It forces them to spend too much time by themselves. And when they’re alone, they’re in bad company.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

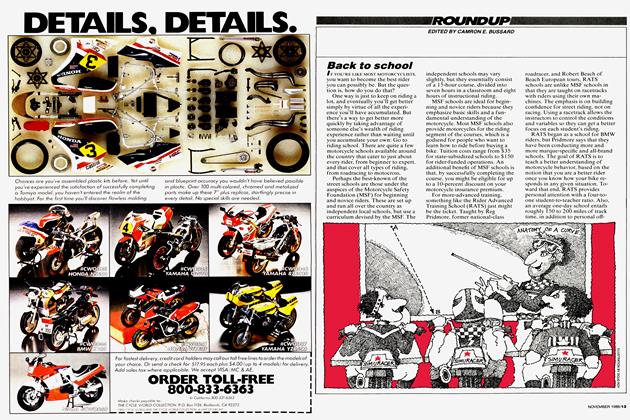

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

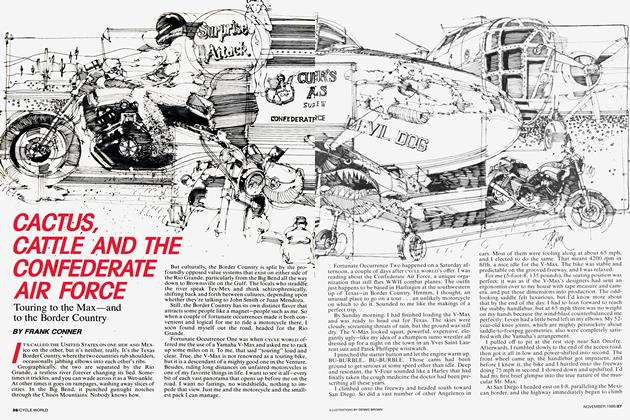

FeaturesCactus, Cattle And the Confederate Air Force

November 1986 By Frank Conner