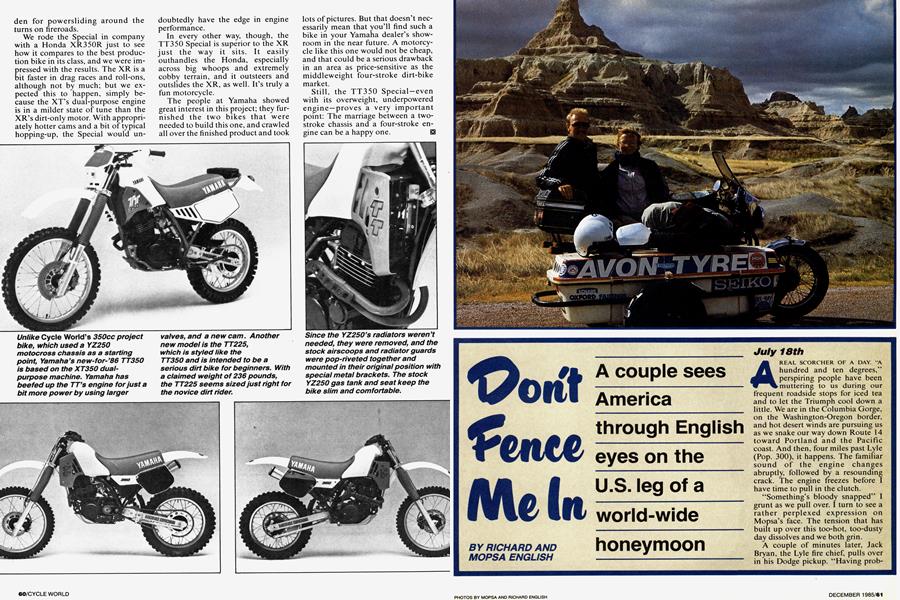

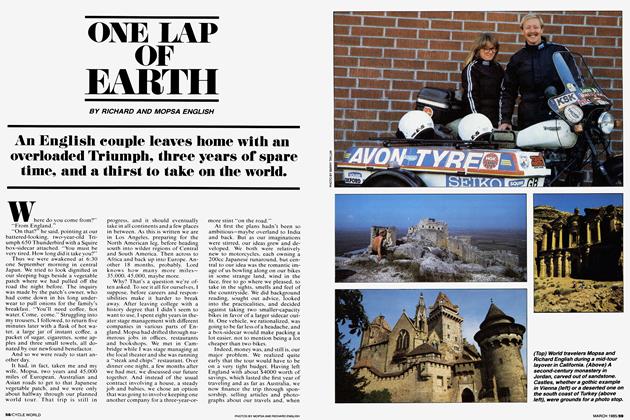

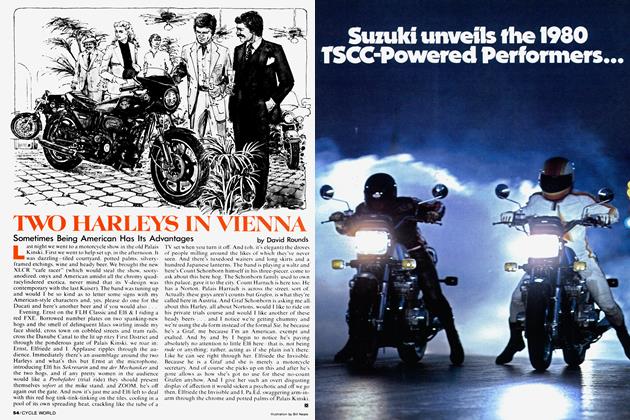

Don't Fence Me In

RICHARD

MOPSA ENGLISH

A couple sees America through English eyes on the U.S. leg of a world-wide honeymoon

July 18th

A REAL SCORCHER OF A DAY. "A hundred and ten degrees,” perspiring people have been muttering to us during our frequent roadside stops for iced tea and to let the Triumph cool down a little. We are in the Columbia Gorge, on the Washington-Oregon border, and hot desert winds are pursuing us as we snake our way down Route 14 toward Portland and the Pacific coast. And then, four miles past Lyle (Pop. 300), it happens. The familiar sound of the engine changes abruptly, followed by a resounding crack. The engine freezes before I have time to pull in the clutch.

“Something’s bloody snapped” I grunt as we pull over. I turn to see a rather perplexed expression on Mopsa’s face. The tension that has built up over this too-hot, too-dusty day dissolves and we both grin.

A couple of minutes later, Jack Bryan, the Lyle fire chief, pulls over in his Dodge pickup. “Having problems?” he asks. We explain. His friend goes back to the pickup and pulls out two cold beers. “I think you’ll be needing these.” Then they tow us back into Lyle.

January 28 th

Almost six months and 16,000 miles prior to our Lyle engine failure. We leave the smog, the congested freeways and many newfound friends in Los Angeles. We are excited to be back on the road again, after a threemonth stopover from our world tour that had already taken in 45,000 road miles through Europe, Asia, Australia, Southeast Asia and Japan. Our ideas of the States have largely been formed by the popular songs of our youth and the mass of films and television programs the Americans export so well. It seems, as we look at the map, that every state, even every town, has a song to go with it. The quintessential image is of the loner, the rugged individualist riding off into the sunset, traveling where he pleases across the vast expanses, doing what he thinks right when the time comes. A far cry from the urban sprawl of Los Angeles that we have just fled, with its McDonalds, Taco Bells and convenience stores every few hundred yards. But we have our faithful steed, the sun on our backs, and a cold wind biting at our faces as we ride over the Anza-Borrego mountains to see the desert spreading out before us to the East.

We sing the words of Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” as we cross the scrubby desert in the rain. Wet, cold weather has greeted us, as have some of those wandering romantics Porter felt so akin to. Row upon row of recreational vehicles spread out across the horizon like some huge, encamped army. It seems that the whole of retired America is on the move in Winnebagos—“Snowbirds,” we hear them called—and they are our constant companions as we travel the Southern states, always friendly and ready to chat. The Mosers present us with their card: “Hello, we are the Mosers. General delivery, U.S.A. South in winter, north in summer. No job—not looking. Our social security tax at work. No phone, no schedule, no worries.”

February 9th

We’re on Interstate 10 and it’s still pretty chilly. It’s hard not to use the interstate across southern Arizona and New Mexico, because there are so few other east-west highways. The desert scenery with snow-capped mountains around Tucson has been magnificent, but soon enough we discover that motorcycles shouldn’t travel on interstates, a fact driven home as mile upon mile rolls past with regular monotony. Lordsburg, a pale, dusty, rundown town, boasts four campsites, 10 motels, 1 1 restaurants and 17 modern service stations on consecutive roadside billboards, but little reason to stop. And Derring has the fastest duck-race in the west. (The city motto: Pure Waters and Fast Ducks).

We push on, through Las Cruces, to camp below a mountain ridge overlooking the White Sands missile base. Huddling against the cold around the fire, we gaze in awe at the myriad stars in the clear desert sky and sing more Cole Porter to lull us to sleep.

In the morning we are greeted by white, white gypsum dunes against a backdrop of grey-pink craggy mountains—a very special place, White Sands National Monument.

February 11th

Early morning, and we pull into White’s City, close to the entrance to Carlsbad Caverns. It’s a tackily painted town of “old-time” plywood facades fronting overpriced curio shops. We warm ourselves on coffee after a below-zero night in the open, and observe as an embarrassed father, closely watched by his two young boys, tests out his quick-draw technique against a plaster cowboy. Well, we are getting close to Texas.

We cross into the Lone Star state and skirt the Guadalupe range, with Signal Peak sharp and golden against a clear blue sky. A long day’s ride on a lonely road follows, through flat, sparse pasture land to Big Bend and the Rio Grande. We pass the odd pickup truck, gun-rack mounted in the rear of the cab, and a lazily raised hand from the Stetsoned driver. “Drive friendly,” ,we are constantly admonished by the roadside signs, and most people do exchange a grin or a wave.

February 15th

The Texas landscape is beginning to change; a gently undulating road, a green pasture, rich soil and clumps of trees to either side; white picket fences and ranches and oil wells grinding on in perpetual motion. We stop at the campsite in Gonzales, Texas, a small town on Alternate Route 90. Wiley Watson, the concessionaire, invites us up to the bar for some Lone Star Lites after we’ve set up camp. Country-and-western blares from the juke box, and some Mexicans are playing pool.

“We ain’t never had no one from England visit with us here,” says Denny Thibodeux, a watery-eyed Cajun, who is enraptured by Mopsa’s accent. “Ain’t theirs the cutest accent, ” seconds his friend Jeannie.

Ricky, the weigher at the local cattle auctions, invites us to come along to see the action in the morning. Then he asks us, confidentially, if it’s true we all eat horsemeat in England. “Well, no,” we reply. “Oh, y’all do now,” he shoots back. “Ask anybody ’round here. All our horses go to England for meat. What they don’t eat in New York, that is.”

The following morning we sit, fascinated at the auction while the cattle pass before us, and over the loudspeaker comes the unintelligible patter;“ ... de dum de dum 65 65 de da de da 66 66 de da, got two folks here from England with us today, visiting by way of Japan. On a motorcycle, yeah. De dum 66 66 67 67 67, sold! Get ’im out o’ here. Next ... 58 58 . . ..” We grin at each other and vow to avoid interstates from now on.

I have always imagined that a motorcycle was the only way to see America, ever since Easy Rider and the cult of the Sixties. Ánd here we were, living out that particular fantasy. But it’s 1985 and things have changed. Motorcycling has become respectable, a recreational activity in a society that puts so much emphasis on leisure and pays out hard bucks to enjoy itself. Our traveling is made very easy; campsites and services are plentiful and easily accessible. People speak the same language—more or less—and we have to guard against a creeping complacency that often tries to persuade us to take the softest option, the straightest road or the most available camping place. Adventure and interest have to be sought out in America, for they don’t just exist here as they have through most of our tour.

February 24th

It’s been raining off and on for several days. We take a small ferry across the misty Mississippi for the second time today. The Skipper, a Mr. O’Connor, comes down off the bridge. “I suppose you know Geoff Duke, then,” he says playfully while nodding at the Triumph and its British registration plates. Inviting us up to the bridge and out of the rain, he tells us how he used to know exworld roadracing champ Duke when he was a a pilot with Manx Airlines. The world gets smaller with every mile we travel.

Rain, rain, rain, all the way into New Orleans. We get lost and ask a black woman for directions. She puts us on the right road and calls after us as we disappear into the murky twilight; “If you get lost again, just ask the Lord. He’ll show you the way.”

Into Florida, the Sunshine state, and it’s still raining. We begin to see a lot more bikes, loaded down and heading for Daytona Beach.

March 8th

It’s clear and warm as we join the mass of bikes heading for Daytona Speedway. The air is charged with excitement and the roar of revving engines and the smell of hot oil. We meet up with Chris Scott from Los Angeles, whose Supertwins workshop in North Hollywood had overhauled the Triumph for us when we arrived in L.A. He’s busy preparing his Norton, and we are assigned the job of “pit buddies,” clocking his laps and taking snapshots. He does well in this, his second Daytona, coming in fourth in the lightweight-modified Battle of the Twins race.

Our time as pit crew done, we head for the town’s famous drive-on beach and get caught up in the look-at-me show that for many is the sole reason for coming to Daytona.

March 20th

We pass south through Fort Lauderdale. Joel Eliel Gonzales is a postman of Cuban descent, a bit of an actor, and a fine mimic of a crusty, upper-class Englishman. But mainly he puts out the magazines for the International Triumph and Ducati Owners’ clubs from his disorganized shack of a house. We talk a lot, eat pizza and drink beer until the small hours, then fall asleep surrounded by mounds of Triumph and Ducati Tshirts.

April 6th

It’s the first day of trout season, and the fishermen are out in force. We’re on the Blue Ridge Parkway, the Smoky Mountains misty and ethereal behind us. We’re riding with the spring as we head north—our first proper spring in three years.

We sweep from bend to bend, along the backbone of the Appalachians, as panoramic vistas flick by on left and right, like a stereoscopic magic-lantern show. We race with the clouds until a fierce blizzard finally engulfs us, obliterating the valleys from view. We descend, freezing and windblown from Skyline Drive, heading north to pit our riding skills against the broken-up and pot-holed roads of inner-city Washington, D.C. Strange that the capital city of the richest, most powerful nation on earth should have such areas of illmaintained roads and so much urban blight. But then, the third world doesn’t hold a monopoly on poverty.

April 14th

The past is trying to catch up with us. Horse-drawn buggies are parked outside supermarkets and quaintly folksy people are at work in field and yard with strictly non-mechanical tools and 18th-century clothing. Telephone and power lines are barred entry to the spotless, whitewashed farmsteads on the gentle slopes of Pennsylvania’s Lancaster Valley. We’re passing through a predominantly Amish and Mennonite area and are beginning to appreciate the anachronisms and contrasts of a nation made up of so many nationalities and religious sects.

And then we hit New York. The towering skyline of Manhattan reveals itself, twinkling in the dusk like some great medieval citadel as we course over elevated highways. We’re swept along by the rushing traffic to drop down into the dank darkness of the Holland Tunnel and are spat out into the colorful chaos that is Chinatown. This is city riding at its most exciting as we try to find a way out and over to Long Island where friends await us. We have grand plans for the Big Apple, but end up walking—and loving every street and avenue, every edifice, made so familiar in all those movies and TV shows.

May 6th

Hartford, Connecticut. Paul Essenfield of Northeast Riding magazine arranges a garage for us to do a little maintenance. I’m greeted by an elderly and slightly depressing Harley fanatic. “Glad to see you’re not riding a Jap bike,” he thrust out immediately. “I fought them in the war. Was one of the first four people into Tokyo after they surrendered.”

“That must have been interesting,” I mumble in reply.

“Yup. When I walked down the street, they all ran away from me.” And then, bringing things more up to date, he let loose with, “Well, is the world in as bad a state as I think it is, then?”

On that cheery note we head north for two weeks in Canada.

May 22nd

We return to the States by way of Detroit, and slowly make our way west, visiting friends and sidecar people in Indiana and Illinois, the Harley factory in Milwaukee, then the gently rolling, pale green hills of Iowa and long, long, straight roads. We are enveloped by the expanse of the Midwest.

June 20th

We’re in South Dakota and the weather is behaving erratically. We have 105 degrees of heat at midday, followed by spectacular electrical storms with high winds in afternoon and evening. The Badlands are truly bad, throwing dust and grit in our faces. Iron Mountain Road with its cleverly engineered switchbacks and tentative views of Mt. Rushmore is an example of road design at its most inventive. A rather radical looking Robert Sckodal from Illinois ap-

proaches us on his rather radical looking Triumph Tiger 100. He’s interested in our bike and wants to know about motorcycle touring in Europe. “I was in England with the Navy, in Portsmouth.”

“Oh yes,” I reply. “That’s where I was born.”

“Got myself a tattoo there. Wanna see?” He thrusts his face closer and curls back his lower lip to reveal “Rock On” tattooed there.

“Didn’t that hurt?” we ask innocently.

We enter Wyoming, cross the Big Horn Mountains where Mopsa is enraptured by the sheer quantity of wildflowers, and arrive in Cody after a violent hailstorm has forced us off the road. There we meet Tetsuyo, a short Japanese fellow with very little English but a strong desire for companionship and an endearing habit of starting every sentence with “Oh, sorry,” as though apologizing for his strange appearance in this strange land. He’s riding a Suzuki 400 from Vancouver to Toronto, then back through the States. He announces that he will travel with us.

We’re glad to have his company, but explain that we travel on a very tight budget, preparing all our own food and avoiding even campsites except where absolutely necessary.

“Oh, sorry, I very interested in cheap travel,” he states, and proceeds each evening to tally up the day’s expenses. Actually, he became somewhat of a fanatic.“Oh, very cheap day!” he exclaimed with delight one evening. “Record cheap day!”

Yellowstone has six inches of snow and almost zero visibility. With some of the money he’s saved, Tetsuyo buys a liter of gin to help fortify us against the cold. The following day the weather has cleared a little, though not our heads, but for a wilderness area there are just too many people about; so we move on.

We camp in Montana, where bear warnings are prominently on display. The next morning, Tetsuyo emerges from his tent a little pale. “Oh, sorry!” he blurts out, suddenly aware of the knife he is still clutching, and with which he has slept. “I hear noises. Not good sleeping.”

June 29th

In Kalispell. Tetsuyo must leave us—he has some hard riding if he is to get back to Vancouver and his flight home to Japan. Our ride now takes on a dream-like quality as we climb the narrow road through Glacier National Park, the landscape violently etched by scouring ice. Precipitous cliffs, razor-sharp ridges, walls of ice. The flat, flat plain around Calgary and then the Canadian Rockies. Expansive and spectacular. Unforgettable and deserving of their reputation as one of the world’s most beautiful mountain ranges. Clear air, golden light, perfect weather. We feel moved, and grateful.

At a stoplight in Vancouver, a BMW pulls up alongside. “Saw your story in Cycle World” he says. “Good to see you.” That’s happened a fair bit—friendly readers this magazine has.

July 19th

Lyle, Washington, the site of our Triumph’s Waterloo. The heat shows no signs of abating. We put through a call to L.A.

“Supertwins workshop. Chris Scott speaking.”

“Hello, Chris. Look, we’ve thrown a rod . . . no, no idea how it happened. Anyway, we’re renting a truck to get the outfit back so you can rebuild it. . . see you in a week.”

We reluctantly accept the indignity of driving our last 1000 miles back to L.A. in a truck. We try to pay lip service to the countryside, visiting Crater Lake, the Giant Redwoods, Yosemite, a little part of Route 101, so beloved by motorcyclists all over the country; but it isn’t the same, and somehow the enthusiasm is lacking. We sit sweating and shackled in our enclosed cab, and watch enviously as the touring bikes roll by.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

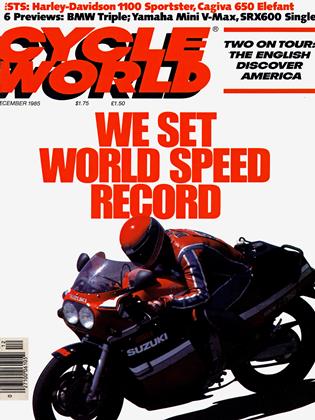

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart