HARLEY MOST RACE

HARLEY-DAVIDSON'S EIGHT-VALVE RACER DOMINATED THEN DISAPPEARED

ALLAN GIRDLER

RACING WASN’T PART OF THE ORIGINAL HARLEY-Davidson plan. Competition, surely: Founders and family took part in reliability runs and other amateur contests when getting from A to B was an achievement, never mind how long it took. But for the first 10 years of the company’s history, during the time competition grew from two guys headed the same direction on the same road to fully professional contests, Harley-Davidson took no official part in racing.

Then, probably for reasons of morale as much as money, the founders changed their minds and on July 4th, 1914, fielded a factory racing team. The venue was Dodge City, Kansas, by then a classic event; the distance was 300 miles around a dirt ring. Harley entered six machines, modified versions of the 61-cubic-inch V-Twin streetbike. Four broke and two finished, well off the pace.

Compressing vast amounts of hard work and heroism, and a soupçon of lucky guessing, the team became competitive in 1915, but no more than that. This was a glorious era. Those who believe we’ve just now invented the modern engine would benefit from a look back at those days. Overhead camshafts, multiple-valve heads, exotic materials and a host of such technology were in place before the First World War.

The racing was different and yet similar at the same time. Sports enthusiasts were still competing, but the big leagues

were for the Pros, on banked wooden speedways, boardtracks as they were known, or full-mile ovals of packed dirt, horse tracks yanked into the industrial age. And there were professional hillclimbs, the easiest way to get up a contest. This was a time when politicians and preachers went on for hours, so the public had no trouble with, indeed may have insisted on, races of 200or 300-mile duration on the mile tracks. The guys didn’t get rich, but they did make more money and meet more girls than if they’d stayed on the farm or in the store.

There was a good crop of strong motorcycle makers at the time: Indian, Excelsior, Emblem, Merkel and the amazing Cyclone, which never made a dime or did much on the road, but which had overhead camshafts while the others still made do with side-valve designs.

Perhaps the most common link between then and now is that then, as now, power cost money. The team bikes needed more power, but not even Harley-Davidson was willing to spend what it would cost for a completely different engine. Instead, in 1916, Harley introduced what we’d call a production-based racing engine.

Many details have been lost to time, but let’s begin with the main components. By the scant evidence available today, Harley-Davidson’s racing engineers used engine cases, flywheels and other basics from the road-going F engine, a two-valve-per-cylinder, inlet-over-exhaust design. They kept the F’s bore and stroke of 3 5/i6 x 3 '/2 inches, for a displacement of 61 cubic inches-by no coincidence the limit for the principal races.

The major engine change was to the cylinder heads, which

had two exhaust and two intake valves for each cylinder. The valves operated by a single camshaft in the timing case next to the flywheels, and via pushrods and rocker arms. The theoretical advantage is easy to understand: The better an engine breathes, the more power it has. Four valves provide better breathing than two. Even more basic, having the valves above the pistons, with a direct route for the incoming and outgoing charges, is better than having the valves next to the piston or off to one side, as in the side-valve and inlet-over-exhaust systems.

Until the Eight-Valve came along, full advantage couldn’t be taken of four-valve-per-cylinder technology, mostly because the engineers of the day hadn’t worked out the rules for octane requirements and combustion-chamber shapes. But Harley-Davidson had the services of Harry Ricardo, an English engineer who was the world’s leading expert on combustion chambers and intake flow, and the new engine clearly had the legs on the competition.

The engine had one carburetor, in the center of the Vee, just like the road machines. (Yup, two would have been better. One tuner, England's Freddy Dixon, did such a conversion and it worked, but for the team, one was enough.) Ignition was Bosch magneto. Lubrication was total loss, as in the F and J models, and the Singles, but with both hand and automatic oil pumps. The breather tube from the crankcase was routed to aim at the primary chain. And notice the shiny clamp around the base of our example’s front cylinder. That’s an oiler. The direction of the flywheel’s rotation and the direction of the machine’s travel conspired to splash more oil up the back barrel than the front one, so they used internal baffles for the back and extra feed for the front.

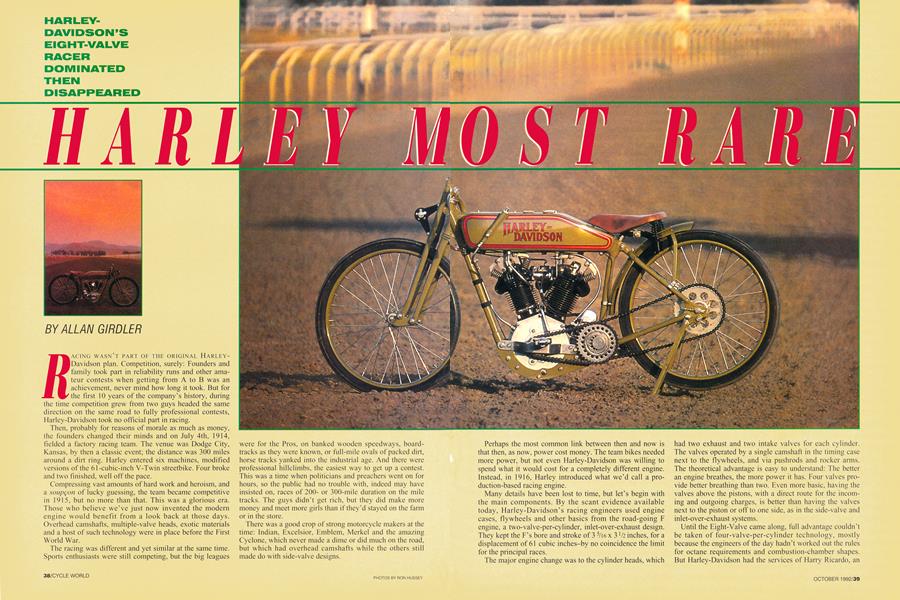

There were three versions of the Eight-Valve engine, with different rocker arms and such, and with either a one-shaft, four-lobe camshaft or two two-lobe cams, as in the example shown here. The 1916 engines had short exhaust pipes, and the later ones—the Eight-Valve pictured is in 1921 trim-had open ports.

Within that span, no two of the engines seem to have been alike. This wasn’t done on

purpose exactly; it was more a case of using the parts on hand, and tailoring the bike for the race it would be in. The basic Eight-Valve, listed in the catalog with year number and an R designation for racing, as in 16R or 17R, was described in the vaguest possible terms. The basic model would seem to have come with hardly anything at all: no clutch, no gearbox, no pedal starter, never mind lights or other road equipment. The mile and boardtrack bikes didn’t use brakes, on the grounds that being able to stop too quickly was risky for the chap behind.

The basic Eight-Valve had only a compression release for starting, meaning you towed the bike, locked in gear with valves lifted off their seats, until there was some speed. When you dropped the lever, compression returned, the engine fired and you let go of the tow rope.

A primary chain ran to the central sprocket-which, in effect, filled in for a gearbox-and a second chain ran to the rear sprocket. Look carefully at the central sprocket. The middle of the assembly is eccentric, so you can adjust the distance from there to the engine, and thus adjust chain tension. They thought things out back then.

The factory brochure says clutch and brake, rear only at the time, were optional. They would have been needed, along with a gearbox, for roadraces.

The lack of facts about the Eight-Valve racers brings up the next point. In the ads, which didn’t tell the prospective buyer much, the prices are listed firmly as $1500 FOB Milwaukee for the Eight-Valve, $1400 for the four-valve racer, which was the same machine but with only the rear cylinder fitted to the cases, making it eligible for Pro classes on smaller tracks. Arch-rival Indian, meanwhile, priced its eight-valve racer at $350, and the four-valve version at $300.

Surely this can only have meant that the HarleyDavidson factory didn’t want anybody outside the factory to buy one of the racers, and the Indian factory did. The record is so vague here that all we can glean is that at least six Eight-Valves were built and there may have been as many as 10,

with eight the middle estimate. Not even Steve Wright, the racing historian who’s spent years on research and even built dazzling replicas of the Eight-Valve’s heads, knows for sure.

Whatever the number of bikes, the Harley team used them to good effect. In 1921, it won all the national championship races. Every blessed one, easily justifying the “Wrecking Crew” nickname the newspapers had attached to the team.

But just before the start of the 1922 season, HarleyDavidson disbanded the team. Why? Historian Jerry Hatfield says his research indicates that enthusiasm for racing had waned, at the boardroom level anyway, and that winning and selling didn’t seem as closely linked as previ-

ously thought. According to Hatfield, Walter Davidson, in particular, was ticked off because Harley won Dodge City four times straight, yet the Dodge City Police Department kept on buying Indians.

That’s foolish enough to be true. In any event, the team was dismissed. The riders and tuners became privateers. They went back to racing with and against each other on souped-up two-valve engines, as they had before the factory fielded a team. The Eight-Valve machines were never seen in the U.S. again.

This is the sort of history one can’t invent. Remember, the bikes were deliberately priced so they wouldn’t sell, and there’s no record of an Eight-Valve ever leaving the racing shop for private hands. The guys who know, Hatfield, Wright, and restorers John Cameron and Pete Smiley, guess that the most likely reason is that they were junked.

Shock! Horror! Don’t forget, nostalgia is a lot better than it used to be. Back in 1922, nobody cared about racing history, they just wanted to be racing’s future. So there was no use for the engines in the shop, and outside they’d only be an embarrassment. If they won, they’d make the factory look bad, if they blew up, ditto. Smiley has even seen some bashed Eight-Valve parts.

This turn of events so frustrated Steve Wright that in 1980, he decided to build an Eight-Valve out of the components available, spending countless hours and the sort of money that makes one hide the receipts from one’s wife. He started with a two-valve racing Single, a 22-S, which used a “keystone” frame identical to the Eight-Valve’s, then installed a two-cam F bottom end. Because there were no four-valve heads to be found, Wright commissioned a new set of patterns and castings. Willie G. Davidson now owns the bike.

You may be musing at this juncture, that if none of the Eight-Valves escaped from the team and there were only six, eight or 10 in the first place, how’d we get these new photos of what’s obviously the real thing?

By happy chance, Harley-Davidson was a power in the motorcycle business worldwide, with dealers and distributors everywhere there were roads and fuel. There was racing worldwide, too, and the more influential dealers prevailed upon the home office to ship over some-we don’t know how many in this case, either-of the Eight-Valves for their local stars to use.

The most complete survivor lives in, of all places, Italy. It’s an especially odd example because it has a clutch, a three-speed gearbox and a loop frame, indicating that the Italian connection wanted a sporting roadbike and used

Harley-Davidson’s top engine, the EightValve, to power it.

At least two of the overseas EightValves have come home to roost. John Cameron’s bike, now owned by Daniel Statnekov, of Tesuque, New Mexico, was brought back from England, where it was raced by Freddy Dixon. Because Cameron wanted to run the bike in the Bonneville speed trials, he parked the original cases and used the lower end from a two-cam road engine. Further, when the machine came home, it was fitted with a stretched frame, to accommodate a clutch. Current owner Statnekov is carefully rebuilding the race-version lower end and he still has hopes of finding an original short-coupled frame.

Meanwhile, the bike pictured here is as close to a true example as anybody has come since the Eight-Valves disappeared. Owner Pete Smiley turned up an engine in New Zealand. “It was a shell, no flywheels or other internals, and I didn’t even know the man had the frame,” says Smiley. But he did, albeit bent out of shape. That was no problem for Smiley, who ran his own speedway team and did special projects for NASCAR and Indy teams. Plus, because he’d already been restoring racebikes and was plugged into the network, Smiley rustled up the tanks and other cycle parts.

The actual engine represents what could have been done by a well-connected private owner of the time, had there been any. The heads are so authentic they were used to make the patterns for Wright’s reproductions, while the cases are two-cam F, from the road-going 61 of 1921. Except that way back then, the factory had special engines with optimum balance and maximum clearances. They were coded with numbers that began with 500. What Smiley has here, Eight-Valve heads atop cases marked 21FH523, is what could have been raced in 1921.

How fast were the Eight-Valves? On February 22, 1921, at the mile boardtrack in Fresno, California, Harley teamster Otto Walker topped time trials with a clocking of 107.78 mph for a flying lap, and won the 50-mile main event at an average of 101.43 mph. It was the first motorcycle race in the world to be won at a speed of more than 100 mph, and it would take more than 60 years for mile races to be won at those velocities again.

They were brave men in those days. With machines to match. □

This article was excerpted from Allan Girdler’s latest book, Harley-Davidson: The American Motorcycle, featuring photography by Ron Hussey. A look at 25 significant Harleys, the book is available from Motorbooks International, P.O. Box 1, 729 Prospect Ave., Osceola, WI 54020; 800/826-6600.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue