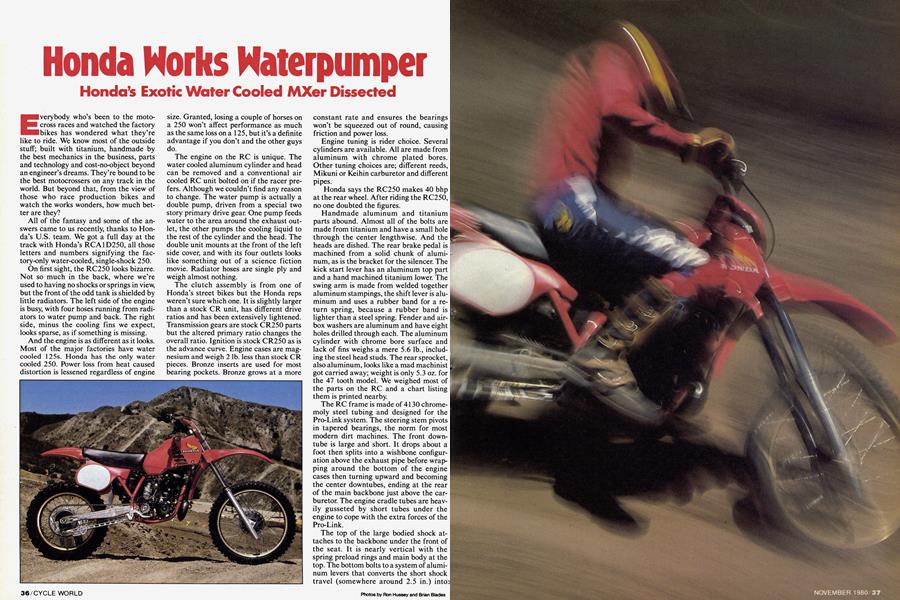

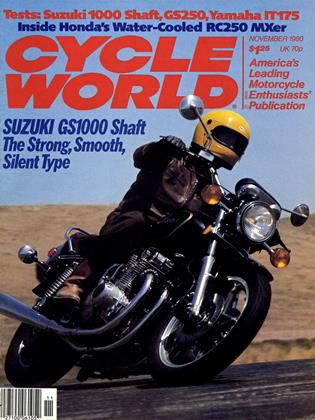

Honda Works Waterpumper

Honda's Exotic Water Cooled MXer Dissected

Everybody who's been to the motocross races and watched the factory bikes has wondered what they're like to ride. We know most of the outside stuff; built with titanium, handmade by the best mechanics in the business, parts and technology and cost-no-object beyond an engineer’s dreams. They’re bound to be the best motocrossers on any track in the world. But beyond that, from the view of those who race production bikes and watch the works wonders, how much better are they?

All of the fantasy and some of the answers came to us recently, thanks to Honda’s U.S. team. We got a full day at the track with Honda’s RCA1D250, all those letters and numbers signifying the factory-only water-cooled, single-shock 250.

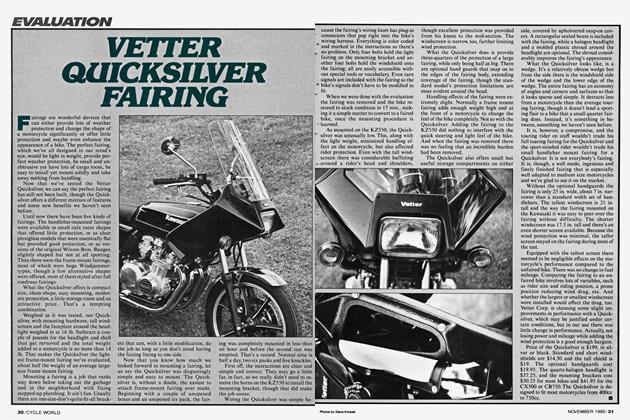

On first sight, the RC250 looks bizarre. Not so much in the back, where we’re used to having no shocks or springs in view, but the front of the odd tank is shielded by little radiators. The left side of the engine is busy, with four hoses running from radiators to water pump and back. The right side, minus the cooling fins we expect, looks sparse, as if something is missing.

And the engine is as different as it looks. Most of the major factories have water cooled 125s. Honda has the only water cooled 250. Power loss from heat caused distortion is lessened regardless of engine size. Granted, losing a couple of horses on a 250 won’t affect performance as much as the same loss on a 125, but it’s a definite advantage if you don’t and the other guys do.

The engine on the RC is unique. The water cooled aluminum cylinder and head can be removed and a conventional air cooled RC unit bolted on if the racer prefers. Although we couldn’t find any reason to change. The water pump is actually a double pump, driven from a special two story primary drive gear. One pump feeds water to the area around the exhaust outlet, the other pumps the cooling liquid to the rest of the cylinder and the head. The double unit mounts at the front of the left side cover, and with its four outlets looks like something out of a science fiction movie. Radiator hoses are single ply and weigh almost nothing.

The clutch assembly is from one of Honda’s street bikes but the Honda reps weren’t sure which one. It is slightly larger than a stock CR unit, has different drive ratios and has been extensively lightened. Transmission gears are stock CR250 parts but the altered primary ratio changes the overall ratio. Ignition is stock CR250 as is the advance curve. Engine cases are magnesium and weigh 2 lb. less than stock CR pieces. Bronze inserts are used for most bearing pockets. Bronze grows at a more constant rate and ensures the bearings won’t be squeezed out of round, causing friction and power loss.

Engine tuning is rider choice. Several cylinders are available. All are made from aluminum with chrome plated bores. Other tuning choices are; different reeds, Mikuni or Keihin carburetor and different pipes.

Honda says the RC250 makes 40 bhp at the rear wheel. After riding the RC250, no one doubted the figures.

Handmade aluminum and titanium parts abound. Almost all of the bolts are made from titanium and have a small hole through the center lengthwise. And the heads are dished. The rear brake pedal is machined from a solid chunk of aluminum, as is the bracket for the silencer. The kick start lever has an aluminum top part and a hand machined titanium lower. The swing arm is made from welded together aluminum stampings, the shift lever is aluminum and uses a rubber band for a return spring, because a rubber band is lighter than a steel spring. Fender and airbox washers are aluminum and have eight holes drilled through each. The aluminum cylinder with chrome bore surface and lack of fins weighs a mere 5.6 lb., including the steel head studs. The rear sprocket, also aluminum, looks like a mad machinist got carried away; weight is only 5.3 oz. for the 47 tooth model. We weighed most of the parts on the RC and a chart listing them is printed nearby.

The RC frame is made of 4130 chromemoly steel tubing and designed for the Pro-Link system. The steering stem pivots in tapered bearings, the norm for most modern dirt machines. The front downtube is large and short. It drops about a foot then splits into a wishbone configuration above the exhaust pipe before wrapping around the bottom of the engine cases then turning upward and becoming the center downtubes, ending at the rear of the main backbone just above the carburetor. The engine cradle tubes are heavily gusseted by short tubes under the engine to cope with the extra forces of the Pro-Link.

The top of the large bodied shock attaches to the backbone under the front of the seat. It is nearly vertical with the spring preload rings and main body at the top. The bottom bolts to a system of aluminum levers that converts the short shock travel (somewhere around 2.5 in.) into> 11.8 in. of rear wheel travel. The levers move the bottom of the shock back and forth slightly, and up and down around 1.5 in. Precise figures would give away too many secrets only Honda knows. The complete system is more complex than it first appears. The lengths of the components have changed some since the first design appeared; any small change in the length of any part dramatically changing the action.

Several design advantages are apparent with the Pro-Link system. First, shock movement is much slower than rear wheel movement, simplifying shock valving. The slower shock movement means hydraulic fluid doesn’t have to move through the damping orifices as fast, reducing foaming, internal heat, and subsequent fluid breakdown. Next, the shock unit is closer to the center of the bike, reducing the polar moment of inertia. Turning and rider input are enhanced because the mass isn’t at the extremes of the machine. Third, the placement and leverage inherent in the design demands a long swing arm and heavy shock spring. The combination means the rear wheel will follow the ground better, the high leverage forcing the rear wheel through dips instead of skipping across them. Lastly, the forces involved on the system means good materials like chromemoly and hardened aluminum must be used to keep the bike from breaking in two. Not really a benefit to you and me until (if and when) it becomes a production machine. Then we all win.

The works Hondas are modified to fit the style and preference of each rider. Each has a choice of forks, Showa or KYB; choice of rear shock, Showa, KYB or Fox; choice of seat thickness, footpeg height, handlebar shape and height, throttle, hand levers, grips, tires, wheel rims, three shift lever lengths and two styles of ends, reed valves and engine tuning. The amount of suspension travel varies according to rider preference and track condition also. In effect, they are one-off customs. Another option is the steering head rake. The frame is set at 30° but different triple clamps with 27 to 33 ° are available to the team riders. Our test bike had a 31 ° rake, 39mm Showa forks, KYB shock, a 36.7 in. seat height, 15.5 in. footpeg height, measured 21.3 in. from the top of the pegs to the top of the seat, and 32 in. wide bars. Tires for our bike were a 3.00-21 HighPoint Red Dot front, and a 5.10-18 Dunlop K290 with a soft rubber compound rear. Spokes were stock CR250 laced to D.I.D. rims but Sun rims are usually used when racing on the hard ground of southern California.

Weighed on our certified scales, with half a tank of fuel and full of water (Water! Who would have thought!) the RC250 weighed 216 lb.

That’s not much more than a good 125. And seeing as how a production CR250R comes to the starting line at 220 lb. or so, depending on what the owner has done, that’s not as light as we expected. The liberal use of expensive metals would lead one to believe it lighter. Most of the weight is in the heavily gusseted frame and large suspension components. The engine actually weighs 7.5 lb. less than a production CR250 unit (48.5 lb. RC, 56 lb. CR). But, by the time the radiators, hoses, water, etc. are added, engine weights are almost identical. The 4 lb. difference between production and works is the result of the magnesium and aluminum trickery. The cost per pound of weight reduction for these parts has to be astronomical.

The big advantage given the factory rider became obvious when we got to the track. Works bikes are semi-custom, remember. We watched as team mechanic Brian Lunas topped up the 2.8-gal. tank with gas and Bel-Ray MC-1, filled the radiators with 3.5 pt. of distilled water, started the engine and let it warm to 92° C. ( 197.5 ° F.) and then put on the radiator cap. This gets air bubbles out of the system and lets the water expand. Honda says the temperature will stay at design level no matter how long the moto or hot the track.

Next, more secrets. The various settings are rider preference but the mechanics are part of the team and the decisions and they keep notes. Lunas knew the track and that our first rider was a pro-class rider, racing weight 160 lb., so he set the tire pressures and rear shock damping. Then the rider climbed aboard and Lunas dialed in the fork pressure and shock spring preload, aiming for the loaded ride height he figured would give the best performance, for this rider on this bike at this track.

What he wouldn’t do is tell us just how much sack was right, nor could we whip out the tape measure and see for ourselves. About 3 in. rear, 2 in. front is our best estimate.

During all this the riders were walking ’round Lunas and the RC, taking mental notes and fidgeting. Finally all was ready. The first man climbed on, clicked the bike into 2nd and dropped the clutch. All watchers were awed as we listened to the rider shift through the gears as he shot up the hill, with the wheel staying off the ground, indifferent to gear selection. A vertical wheelie is one thing, holding the wheel close to the ground through all the gears is a clear indication of brute power. The RC250 doesn’t act or sound like a 250. More like a crisp 360. Suddenly the claimed 40 bhp at the rear wheel seemed right.

Handling is neutral and totally predictable. Acceleration and handling are like you would expect from a 360 engine in a 125 frame. The bike can be pitched into a corner or simply ridden through.

Suspension compliance is good at the front, great at the rear. The Pro-Link rear shock arrangement is the best single shock system we have tried, but then we are comparing a works bike to production bikes. The back never kicks or bucks and almost feels too soft until you realize it never seems to wallow or bottom, or at least the rider is never aware of it bottoming. The 39mm Showa forks are good also. They are compliant and don’t bottom harshly but aren’t as good as the 44mm Fox Forx. Don’t be mistaken, they are good but don’t match the strength or give the absolute steering precision of the giant Fox units.

The brakes on the RC are best described as touchy. The front stops strongly and predictably but the rear . . . our riders kept killing the engine with the rear brake until several laps were completed. Our test bike had a long pedal, another rider choice (Works riders have three lengths to choose from), so a shorter one would probably cure our complaint.

Surprisingly, the rider doesn’t feel any heat from the engine or radiator. Normally, a half hour around a MX track in the summer will heat the engine cases to the point of being uncomfortable to the feet of the rider. The cooler-running water pumper doesn’t. And the radiator heat is directed out from the rider by the strangely shaped tank. Additionally, the lack of cylinder fins means the cylinder is farther from the rider’s legs and the exhaust pipe can be tucked in tighter.

We were worried about the bike being top heavy with the radiator mounted high on the front of the frame but it’s not noticed when riding. The bike doesn’t feel any different from a normal air-cooled machine. The credit goes to light metal usage. The radiator (or actually radiators), one each side of the frame connected with a hose, are made from aluminum and the pair only weigh 2.7 lb.! Add the weight of the water, about 3 lb. and the total added weight at the top of the bike is less than a gallon of gas. Honda experimented with lower radiator placements but had problems with mud clogging and damage from rocks flung from the front wheel.

We are extremely impressed with the water cooled Pro-Link. It doesn’t have any of the bad side effects that many single shockers demonstrate and feels superior to dual shock motocrossers in almost every situation. The back end doesn’t kick or buck, even when the throttle is closed over fall away jumps, it is neutral handling, quick steering and precise. Square corners are easy, as are bermed or off-camber ones. None of our test riders could find fault with the handling. And the power-toweight ratio makes the bike a rocket ship. But best of all, the power stays constant through the longest, hottest races. Of course we are comparing a factory racer to production bikes. The factory racers definitely have an advantage over production based machines, although not to the extent most of us think. The water cooling is a definite plus.

HONDA

RC A1D 250

The difference in the rest of the machine isn’t nearly as great as we’ve fantasized. Production based bikes properly set up to track conditions can be almost as good. Marty Moates’ recent win at the 500 USGP proves the point. So don’t complain the next time that factory rider beats you. Sure his bike is a little better and his parts bin better stocked, but the biggest difference lies in his mechanic’s ability to dial the machine in properly.

We questioned the Honda reps about production possibilities of the RC250 Waterpumper. The answer was, “who knows, almost anything is possible.” Certain parts on the bike, things like the die formed pipe, lead us to believe a production bike is just around the corner. If so, the motocross tracks of the world could turn red again

View Full Issue

View Full Issue