CAGIVA 650 ELEFANT

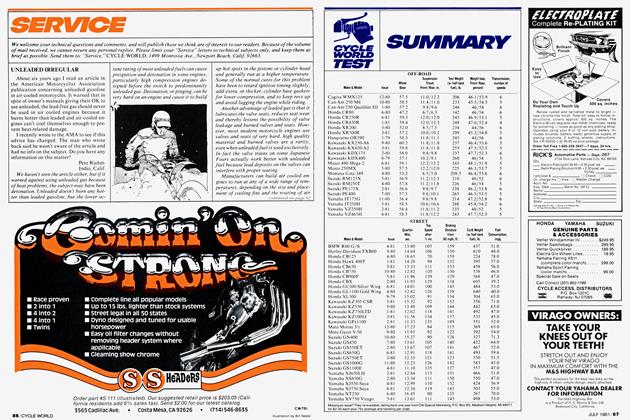

CYCLE WORLD TEST

DUAL-PURPOSE SPORT-TOURING

THIS IS NOT A DIRT BIKE. Repeat: The 1986 Cagiva Elefant 650 is not a dirt bike, not if Huskys or Honda XRs or Yamaha YZs define the category. Expect the Elefant to rival these purist devices—or even smaller dual-purpose machines—in off-road situations, and you will be sorely disappointed. But appreciate this non-dirt bike, this larger-than-life dual-purpose machine, for what it does well, and you may find it’s your ideal motorcycle.

For street riding is the Elefant’s forte. It effortly cruises city streets; it rips down bumpy, twisty two-lanes; it tours comfortably at 65 mph down endless interstates; and it smooths out chuck-holed gravel or dirt roads at speeds that wouldn’t be possible on a pure streetbike. Oh, sure, the Elefant can be ridden off-road, down tight little trails and across open country, but unless that terrain is especially flat and smooth, a 250cc dual-purpose bike will undoubtedly outrun it. No, the Elefant has just enough off-road capabilty to be the perfect long-distance explorer bike.

This combination of strengths and weaknesses can be traced to the Elefant’s 650cc Ducati engine, a 90degree V-Twin that is a member of the Ducati Pantah engine family. Like its relatives, it is a sohc design, with the camshafts driven by toothed belts, with the valves operated in classic Ducati fashion — desmodromically, which, for those of you who don’t know, means that the valves are mechanically closed by the cams as well as opened by them.

New to the Elefant engine is the rear cylinder head; unlike on previous Pantah-family engines, the rear exhaust port on the Elefant faces aft, the intake port to the front, allowing both carburetors to sit in the crotch of the V. Engine tuning is slightly milder, as well, but the results are familiar; smooth, torquey power, with the only vibration being a typical VTwin throbbing that’s more pleasant than irritating.

All in all, the power characteristics are very appropriate for a large-displacement dual-purpose bike; it’s the engine’s weight and configuration that are less suitable. Long, heavy, and not particularly narrow, the Ducati engine has forced this Cagiva into being an eleven-tenths scale dual-purpose bike. The Elefant’s wheelbase stretches out 60.5 inches, and the bike weighs a ponderous 434 pounds without gas. It’s not a motorcycle for small people, and with its 34.5-inch seat height, it’ll have those with shorter inseams on tippy-toe at every stoplight.

Initial impressions come from that weight and size: Upon first sit, the Elefant feels gross and top-heavy. And an initial ride doesn’t do much to dispel that impression, as the Elefant doesn’t have the easy-to-flick feel of, say, an XL600R Honda. But where the Elefant’s chassis is initially off-putting, its engine is engaging. It pulls from the bottom of the rev range, picks up more power above 4500 rpm, and revs out hard to the 8500-rpm redline. Short-shift it during around-town cruising, and it feels happy; rev it out for a quick pass, and it feels happier yet. Despite the extra hundred pounds the Elefant spots the 600cc dual-purpose Singles, it will handily out-accelerate and outrun them. And despite its 150cc handicap, it will do the same to BMW’s R80 G/S.

But that same first ride that highlights the engine reveals two problems. First, the clutch drags, making a normally smooth-shifting Pantah gearbox extremely clunky, with neutral almost impossible to find at a stop. This is ironic, for our test Elefant was one of the first fitted with a new heavy-duty dry clutch intended to increase the engine’s marginal clutch capacity while reducing clutch effort. An earlier Elefant we sampled during Cycle World’s Italian visit (September, Í985) had the older wet clutch that refused to misbehave as did this new, “improved” model.

These problems result from Cagiva’s attempt to reduce clutch effort to Japanese levels through an extreme hydraulic leverage ratio. By using a small piston at the clutch master cylinder, the designers have reduced lever effort, but this has also reduced the travel of the slave piston at the clutch. Thus, clutch engagement begins when the lever is barely a quarter-inch from the handgrip; and even when the lever is touching the grip, disengagement is not complete. We cured the problem by fitting a Honda master cylinder with a larger piston ( 14mm instead of 13mm), but this is really a problem that Cagiva must resolve at the factory level.

The other problem is less significant, but annoying: The Elefant has perhaps the stiffest throttle of any motorcycle we have sampled in recent years, making smooth riding difficult. Dell’Orto seems to live in fear of sticky throttle slides, and so fits its carburetors with return springs that are more suitable for swinging shut the anti-blast doors at Cheyenne Mountain than they are for controlling a carburetor slide. Cagiva’s solution for this is a set of carburetors that use a push-pull linkage and a light return spring; but because of delays at Dell’Orto, only later production Elefants will receive these units. We found a cure in a set of lighter throttle springs available from Dell’Orto distributor Ron Wood (755 W. 17th St., Costa Mesa, CA 92627; [714] 6450393). These reduce throttle effort to a more acceptable level.

With the clutch working and throttle action lighter, we were able to enjoy longer-range impressions of the Elefant. And it’s in the long run that this Cagiva develops its appeal. Like> most dual-purpose bikes, it has suspension that makes short work of any irregularities that can be found on normal roads, and its dirt-bike-style riding position is comfortable. The high-mounted front numberplate/ headlight acts as a mini-fairing, and highway cruising up to 70 mph or so involves no back or arm strain. And unlike most of its smaller dual-purpose brethren, the Elefant actually has a good seat. No attempt was made to give the seat a fashionably narrow motocross width, and the result is a reasonable perch for an all-day ride. The seat is also exceptionally long, which helps the Elefant be as comfortable two-up as anything this side of a Gold Wing.

Once you become familiar with the Elefant, its sporting nature begins to peek through. Good brakes contribute to its on-pavement performance. The single front disc is powerful, and can howl the front tire with a moderate pull. But unfortunately, between the powerful front brake and the Elefant’s weight, the 42mm legs of the front fork are put in such a bind that they twist noticeably during hard braking. Rear disc operation, in contrast, is near-perfect. The brake, which is nicely progressive and requires firm pressure to lock the rear wheel, remains very controllable on all surfaces.

Once acclimated to the Elefant’s size, you find that it can be tossed about. The wide handlebar gives good leverage for quick turning, and a change of line can always be made with a shift of body weight, with no worries about running out of ground clearance. On a twisty road, the Elefant works well up to a 90-percent pace; at those levels, it’s easier to ride than many roadrace replicas, and just as fast. Push harder, though, and the dual-purpose tires start shuffling and drifting somewhat disconcertingly; at these higher speeds, a very smooth riding style is required. Still, the Elefant will cover long stretches of convoluted two-lane quickly without tiring its rider.

If anything is the clue to this bike’s mission, it’s just that: The Elefant, while keeping its rider relaxed and comfortable, will inhale long distances on any road that’s ever seen a motor vehicle. It’s nothing more than a dual-purpose touring bike, with a sporting bent.

You want to ride up the most remote dirt roads in Alaska? Or ride down to the tip of South America? Or investigate every ghost town in the American Southwest? Those are the Elefant’s bailiwick, missions it will perform faithfully and comfortably, missions at which few other motorcycles are directed.

At the same time, the Elefant is good at the more prosaic. It will serve as an around-town cruiser, a backroad sportbike or a freeway droner, and do it all quite well. While it has its liabilities and problems, it remains a motorcycle with considerable charm and personality. And it possesses a level of quality (both of components and of finish) that will shock anyone who had their impressions of Italian motorcycles formed by machines from the 1970s.

To be sure, the Elefant is not a purist dirt bike. Or a purist street bike. Or purist anything, actually. Nor is there even anything quite like it (okay, the BMW R80 G/S comes close). Instead of easy categorization, Cagiva must be satisfied with simply having built a good motorcycle, and hope that buyers can appreciate the Elefant’s unique blend of capabilities.

GAGIVA 650 ELEFANT

$4288

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

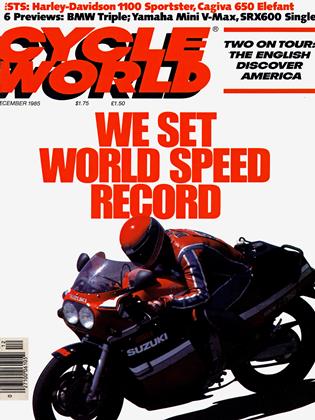

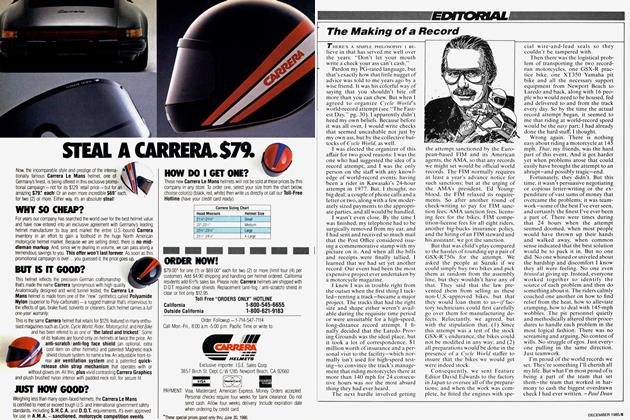

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart