YAMAHA FJ600

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

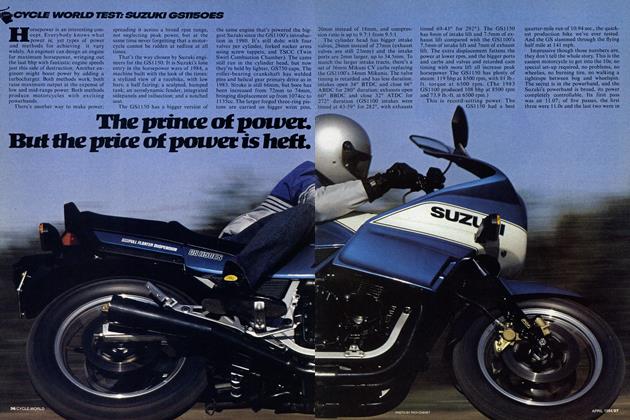

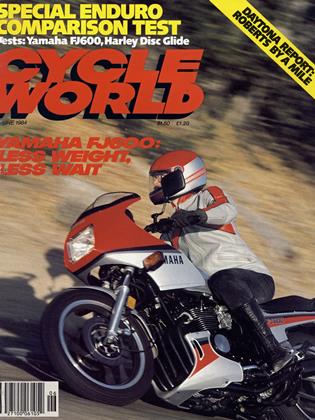

YAMAHA'S CURE FOR THE MID-DISPLACEMENT SPORT-BIKE BLUES.

Despite success in other markets, Yamaha has in recent years displayed a knack for building good sport bikes nobody wants to buy.

The examples are numerous. The sporting, shaft-drive Seca 650 received plaudits from the press, yawns from the public. Seca 650s can still be found languishing in showroom corners, cobwebs across the bars, stale gas in the float bowls and almost $1000 knocked off the price tag.

The Seca 750 didn’t fare much better. Swoopy styling and insert-quarter-here instrumentation didn’t hide the 750’s flaws; it was the most expensive bike in the class, it wasn’t the fastest or quickest and handling wasn’t exactly its strong point. Sales were so poor that Yamaha hung a small fairing, saddlebags and a trunk on the bike and dropped the standard model altogether.

The Vision 550 was a novel approach. A water-cooled VTwin with shaft drive and angular styling, the bike was plagued by problems in its first year, 1982. Yamaha stayed with the bike, though, making improvements to the engine, carburetors', brakes and suspension. Last year Cycle World was so impressed with the Vision that it was chosen as the best 451-600cc street bike in our annual Ten Best awards. A “super do-anything bike” we called it. Anything, it turned out, except sell. For 1984 the only Visions for sale are those left over from 1982 and 1983.

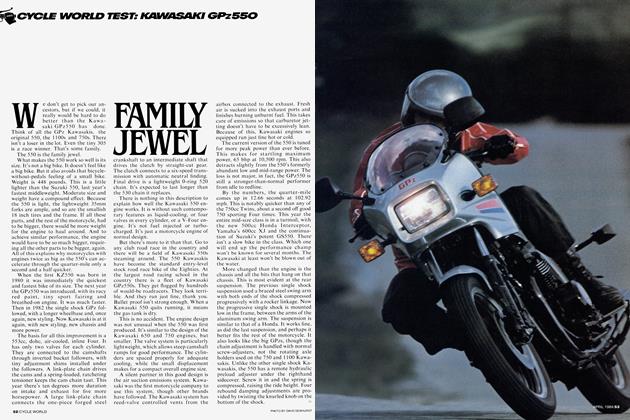

The chain-drive Seca 550, introduced in 1981, came closest to breaking Yamaha’s sport-bike jinx. In effect a four-strokar reincarnation of the all-conquering RD400s, the 550 had the power and handling to go head to head with the just-introduced Kawasaki GPz550. But in the following years the GPz got a stronger engine, single-shock rear suspension and the undisputed class championship, while Yamaha left the Seca unchanged. Sales dropped, and the Seca 550 was discontinued in 1983.

Yamaha learned several things from this. 1) Shaft-drive sport bikes, like the larger Secas and the Vision, don’t sell; 2) sport bikes without top-of-the-class performance don’t sell; and 3) sport bikes that are more expensive than most of the competition don’t sell.

Which is where the 1984 FJ600 comes in.

Yamaha desperately needs the FJ600 to be a sales success, so they went back to what they knew would work. Chain drive. A pumped-up engine. And a price in line with the other bikes in the class, the GPz550 and Suzuki’s GS550.

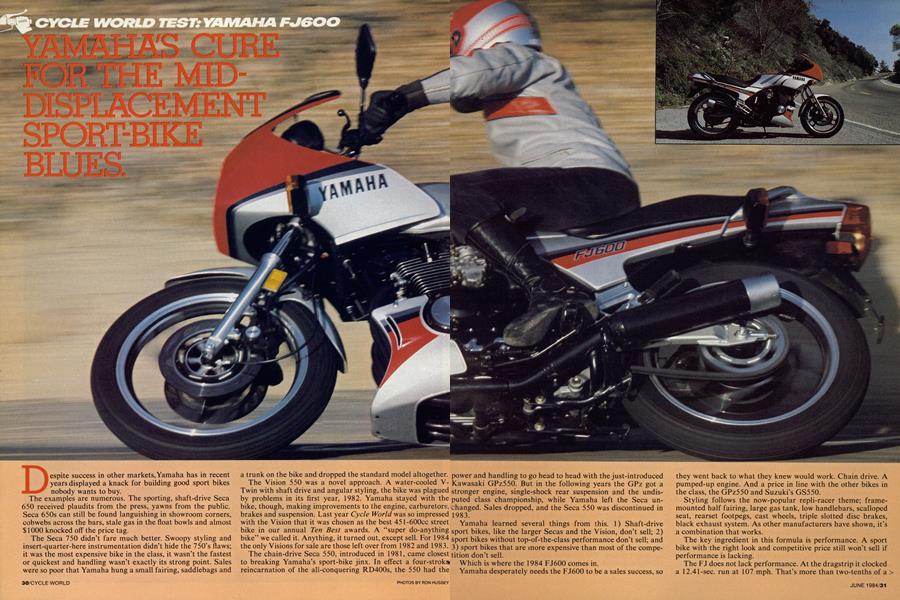

Styling follows the now-popular repli-racer theme; framemounted half fairing, large gas tank, low handlebars, scalloped seat, rearset footpegs, cast wheels, triple slotted disc brakes, black exhaust system. As other manufacturers have shown, it’s a combination that works.

The key ingredient in this formula is performance. A sport bike with the right look and competitive price still won’t sell if performance is lacking.

The FJ does not lack performance. At the dragstrip it clocked a 12.41-sec. run at 107 mph. That’s more than two-tenths of a> second quicker than the 1984 GPz550 tested last month. The time is just two one-hundredths of a second slower than last year’s quickest 550, the Suzuki GS.

More impressive, the FJ's times were taken at a dragstrip considered by the experts to be a tenth of a second slower than the now-defunct Orange County International Raceway, where the Suzuki’s dragstrip testing was done.

More proof? Pee Wee Gleason, star of stage, screen and magazine ads, was at the track during our dragstrip session. He jumped on the bike and promptly fired off a run at 12 seconds fiat with a speed of 1 10 mph. In the right hands, then, on the right track, the FJ will likely be an 1 1-sec. quarter miler.

The impetus for all this quickness is a redline-hungry inline Four displacing 598cc and driving through a six-speed transmission. Not surprisingly, the 600 is based on the Seca 550 which, in turn, was fostered by a 400 that Yamaha first produced for its home market in 1980. The engine doesn't break any new ground for Yamaha. Like the XJ series, the 600 has double overhead camshafts driven by a roller chain running through the middle of the cylinder casting. There are two valves per cylinder, adjusted via shims on top of valve buckets. Twopiece connecting rods are attached to a crankshaft that runs in plain bearings. The generator is behind the cylinders, above the gearbox, allowing an engine width of just 16 in. The electric starter motor is positioned behind the generator.

The new-found power Yamaha claims 72 bhp comes from increasing each cylinder's bore to 58.5mm and increasing the stroke to 55.7mm. The larger bore allows larger valves, the intake valves measuring 31.5mm, the exhaust valves 27mm. The intake valves are opened 42° BTDC and close 62° ABDC, while the exhaust valves open 58° BBDC and close 38° ATDC, with durations of 284° intake, 276° exhaust, all figures up from the 550’s.

Carburetion chores are taken care of by a quartet of 32mm CV Mikunis, breathing through a pleated paper air filter. Ignition is electronic, never needing adjustment. Circulation of the 3.2 qt. of oil through the engine is made easier by the addition of a five-row oil cooler. A metal cylinder head gasket is used on the FJ, the 550's was fiber. The clutch assembly has been fortified with an extra friction plate and heavier springs.

While the engineers were performing the makeover on the 550 engine, they decided to do away with YICS, Yamaha’s Induction Control System. Basically a series of inter-connected sub-ports in the carburetors’ intake tracks, designed to swirl the incoming fuel/air mixture for more efficient combustion, YICS was deemed unnecessary for the 600 because of the new engine’s increased cam timing.

The engine’s rev-happy disposition is in part due to the lightening of the crankshaft, connecting rods and pistons. Indeed, when the engine is at full boil it's hard to keep the tachometer below the 10,500-rpm redline. There really isn’t a point in the powerband where things explode, but from 8000 rpm to redline it's easy to tell serious horsepower is being made.

As impressive as the FJ’s high-rpm surge is, the bike is easy to ride around town. It'll never out-torque a 1 100, granted, but a mild run through the gears won’t leave the rider wondering where all the power is. On smoothly winding backroads the Yamaha can be clicked into sixth gear and left there, with fifth and fourth needed only on hills, or when the going gets tighter or the rider feels the need for some added urge out of corners. Dropping down to fourth is also the preferred procedure for blasting ahead of slow-moving traffic in passing situations.

The impressive engine falls short in two categories, however,, Cold starting and vibration control.

In the morning the FJ requires full choke engagement of the carburetor enrichening circuits, actually and no throttle. The engine catches easily enough, then roars into high idle. Too high, as the engine spins at 3000 rpm. Back off the handlebarmouunted choke control and the engine feels as if it wants to stall. It usually doesn't, it just feels like it will.

Ridden away without a lengthy warm-up, the 600 is flat and lurches around. Adding to the problem, for some reason the choke backs off by itself, forcing the rider to thumb the choke control back to full on at the first stop signs along the route in order to keep the engine running.

In these days of lean carburetor jetting for cleaner emissions, a cold-natured engine is not all that uncommon. And when all is said and done, the problem can be worked around until the bike is a few miles down the road and sufficiently warmed up.

Vibration is not so easily dealt with.

To isolate engine vibration from the rider, the FJ uses rubber engine mounts, two of them. This is an unusual setup. Most chain-drive bikes with rubber mounts have some sort of positive lateral location, either a locating link or one solid mount. This is necessary to maintain sprocket alignment, which, in turn, is critical to chain life. Instead, the Yamaha has rubber mounts that don't allow much deflection. And two mounts instead of the usual three mounts also reduces vibration pickup. What this system doesn't do is isolate much vibration. The FJ is a buzzer. At normal cruising speeds the FJ’s rider has to put up with tingling from the handlebars, seat, footpegs and tank. It’s at its worst about 65 mph, when the the tingling is joined by a resonating sound that seems to be coming from the rubbermounted fairing.

What with all this buzzing, the FJ feels busy at cruising speeds. But in fact, at 65 mph the engine is turning 5500 rpm, not all that high for a mid-displacement Four.

Still, the Yamaha is geareda little low, probably in the hopes of improving acceleration. The FJ will almost pull redline in sixthclocking 1 19 mph. The FJ owner who plans to spend some time touring at a steady speed would be well advised to experiment with a larger countershaft sprocket, relaxing engine rpm a bit and perhaps moving the worst of the buzzing to a different speed.

Installing the larger countershaft sprocket would also improve mileage slightly, although the FJ is no gas guzzler. Ridden moderately, the FJ will return approximately 60 miles to a gallon of gas. On the Cycle World mileage loop, a yardstick of real-world mileage, the bike recorded 56 mpg.

Like the engine, the FJ600’s chassis specifications don’t reveal anything dramatic. There is no square-section perimeter frame as on the FJ 1 100 flagship. There is no 16-in. front wheel. The fork is devoid of an anti-dive system, or even air caps. Rear suspension is via a modern rising-rate single-shock system, but the shock is adjustable for spring preload only, no provision for altering the damping. The box-section swing arm is silverpainted steel, not aluminum, although it does ride on needle roller bearings.

There are several reasons for the bike’s relative austere trappings. Foremost is price. Remember one of the lessons learned with the Secas and the Vision? In the mid-displacement class, price is very important. Yamaha could have fitted the FJ with every go-fast, sales-pitch device known to man water-cooling was even considered but the added cost would have jumped the 600’s price into competition with the tariff-shrunk 700s and maybe even the full-house 750s. Given the same price, most aiders adhere to Bigger is Better Theory and go for the bike with more displacement.

Suggested retail for the Yamaha is $2899; the same as the Kawasaki, $100 less than last year’s list price for the Suzuki and one dollar more than the projected asking price for Honda’s yetto-be-released 500 Interceptor. Price objective met, in other words.

More features also mean more weight. And more weight means the engine has to make more power to attain the same performance. With a 454-lb. test weight (gas tank half full), the Yamaha is 6 lb. heavier than the GPz550, but 9 lb. less than the Suzuki.

So the Yamaha is simple, which means light, which in this case also means fast and quick.

Incidentally, the bike tested here is the FJ600LC. The C standing for California, or more precisely the fuel vapor canister and its accompanying hoses that are required on all 1984 models sold in California. The LC version weighs about a pound more than the 49-state L model.

The frame itself is standard Yamaha, made of round steel tubing. There is a main backbone tube flanked by two smaller backbone tubes. Two downtubes cradle the engine and sweep back on either side to join the other frame tubes behind the engine at the swing arm pivot. Of note here are the swing arm pivot housings. Rather than just round end caps, the pivots are cast with webbing and have large diameter tubing that the frame tubes are welded into. This enables the frame to handle the stresses imposed by the new single-shock rear suspension.

The shock mounts behind the engine and in front of the rear wheel. It is compressed from the bottom by a link attached to the swing arm. Spring preload is changed by turning a wheel attached to the shock’s preload collar via a toothed rubber belt. A 22mm wrench fits on a nut cast into the wheel. To get to the adjustment wheel the right sidecover must first be removed.

It would be easy to criticize the FJ's lack of features if it didn’t work as well as it does. At a Willow Springs Raceway press introduction several months ago, the pre-production 600 impressed everyone with its precise handling, generous ground clearance and strong brakes. Out in the everyday world of potholes, rock-strewn corners, freeway expansion joints and rushhour traffic jams, the production FJ is just as impressive.

Damping adjustments or no, the FJ’s rear shock delivers a cushy freeway ride when the preload is sent on one of the two lowest settings. Venture-like the ride isn’t, but for a sport bike it’s smooth, with little of the hobbyhorse action that afflicts fome other quasiracers. Setting number 3 is a good compromise, allowing a relatively compliant freeway ride but still permitting a good clip on the backroads. For more vigorous riding, settings 4 and 5 need to be dialed up. Anything less and the bike wallows around a bit when ridden aggressively around corners.

Club racers might benefit from fitting a shock with an oilcooling reservoir and adjustable damping, and no doubt well-off canyon profilers will find an excuse to mount a more expensive unit, but for most riders the stock shock will work just fine.

At the other end of the bike a fork assembly with 38mm stanchion tubes, plastic fender, aluminum fork brace and 5.6 in. of travel does an equally capable job. Yes the front end dives when the brakes are applied, but then so do most of the bikes equipped with anti-dive. At least the lack of extra plumbing means that brake feel isn’t impaired, the way it is on some antidive-equipped motorcycles.

On the subject of brakes, the FJ’s are terrific. The three discs halted the Yamaha in 30 ft. from 30 mph and 120 ft. from 60 mph. Those figures aren’t the best ever recorded by Cycle World but they’re pretty close, and they are better, marginally, than the figures logged by the GPz or the GS.

The Yamaha’s riding position is a good compromise for a sport bike. The cast aluminum handlebars rise about 3 in. from the relatively low top triple clamp. Combined with the comfortable seat and mildly rearset footpegs, they allow a rider to cover a good bit of ground in a day without having to stop repeatedly to shake a spasm out of his wrists or unkink a strained neck.

The I-beam-type bars, incidently, attach to the top triple clamp via serrated edges that appear to allow for some adjust ment. Yamaha says no, the serrated edges are there for strengtl only and, in fact, a locating pin is cast into the assembly to mak sure the bars are mounted in one position only.

The plastic half fairing also helps rider comfort. It is supported by its own tube frame that attaches to the main frame at three rubber-mounted points, and although it doesn’t stop the majority of air from hitting the rider, it does do its windbreaking duties effectively, without directing an annoying turbulent blast of wind right at the rider’s helmet.

About the only criticism that can be leveled at the Yamaha’s ergonomics is the lack of space around the rider’s footpegs. The left peg is especially cramped thanks to the rearward-facing shifter and it’s Heim linkage, the sidestand with its various tangs and the double sidestand return springs. Riders who like to place the balls of their feet on the pegs while cornering will find that their heels rest on a non-shielded part of the tucked-in mufflers. Apparently Yamaha is aware of the problem because they provide heel rests on the peg carriers. Unfortunately using the rests skews a rider’s feet at awkward angles, so the rests go unused and the mufflers collect grundgy marks where they contact rubber heels.

The FJ has a simple instrument layout, consisting of three large dials arranged in a shallow triangle formation. The 12,000-rpm tachmeter is mounted in the top position of the triangle with the 135-mph speedometer down and to the left. The positioning takes a little getting used to, but after a few rides looking diagonally from the speedo to the tach becomes, if not natural, at least effortless.

The third dial contains the fuel gauge. Typically Japanese in operation it turns out, as the needle doesn’t move much in the first 50 miles, hovers around the half full mark for a while, then dives toward empty. Empty actually means about a gallon of fuel is left in the 5-gal. tank. For those who don’t like to depend on gauges, the Yamaha retains the standard off/on/reserve petcock.

Turn signal arrowheads, an odometer reset button and indicator lights for high beam, low oil lever and neutral complete the instrument cluster.

Convex mirrors giving a wide-angle view rearward are mounted on stalks that swing the mirrors out and up. The no sitioning allows a better view of things coming up from behinc than, say, a GPz550, but a tuck-in of the elbows is still requirec to see directly astern.

As mentioned, the FJ’s cosmetics follow the curren repliracer trend. From a distance the bike appears to be cleanl) styled. At closer range, however, things start to get slightly busy. The plastic sidepanels and airbox each have a series o built-in ridges, the seat has embossed rectangular panels at the front, rear and sides. The aluminum footpeg carriers have ridges and cutouts, the countershaft sprocket has three circulai indentations and the steel rear brake lever has six cast-in depres sions, perhaps to give the look of a drilled-for-lightness alumi num piece.

The black-chrome mufflers have aluminum-look end caps, a styling exercise Yamaha says is supposed to make the mufflers look smaller.

Another styling exercise is the aluminum tail section top. Almost pewter-like in appearance, the top runs from the large taillight to the rear of the seat before cascading down to forir passenger grab rails. Research has shown that a bike’s tail section is one of its most looked at styling components, and Yamaha wanted to give people something to look at. Whether or not the tail section top is an aesthetic triumph is open tc debate, but it does draw attention.

Styling exercises aside, the FJ600 works. Its price is right. Its handling is on par with the competition. And the thing movqs down the road like the very blazes. It is a very good mid-displacement sport motorcycle.

Yamaha knows only too well that being good sometimes is#’ enough. With the FJ600, that shouldn’t be a problem. E

SPECIFICATIONS

GENERAL

$2899

CHASSIS

SUSPENSION/BRAKES/TIRES

ENGINE/GEARBOX

PERFORMANCE

ACCELERATION

SPEED IN GEARS

FUEL CONSUMPTION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

June 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

June 1984 -

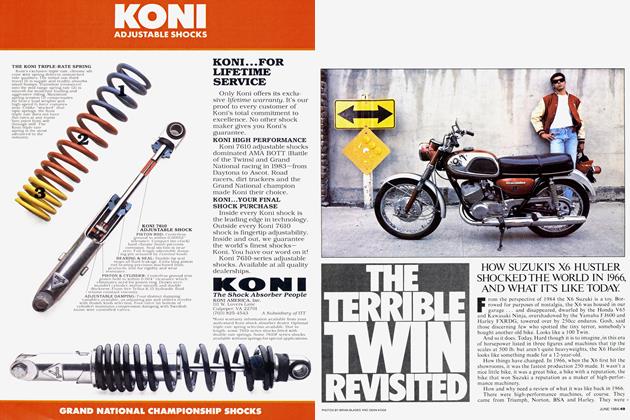

History

HistoryThe Terrible Twin Revisted

June 1984 -

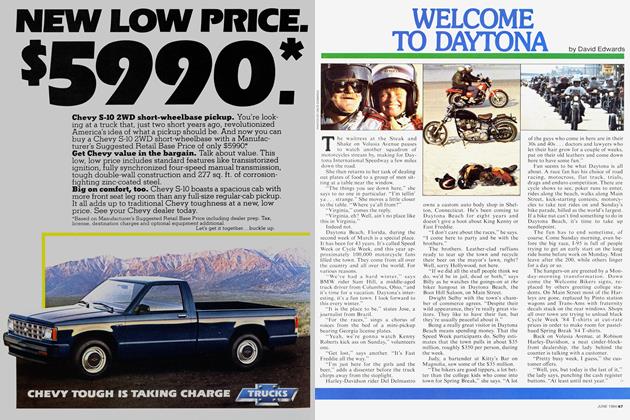

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Welcome To Daytona

June 1984 By David Edwards -

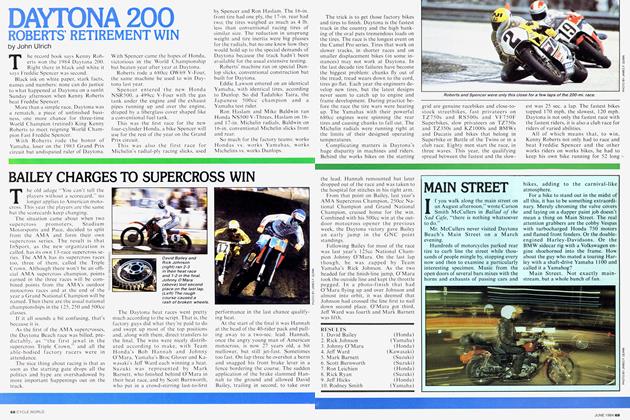

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Daytona 200 Roberts' Retirement Win

June 1984 By John Ulrich -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Bailey Charges To Supercross Win

June 1984