ATP Suzuki GS750

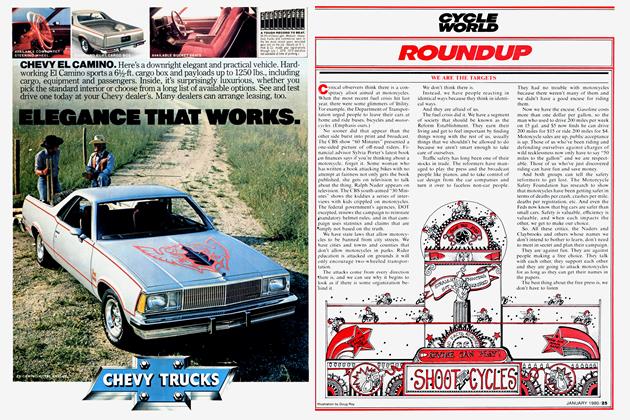

American Turbo Pak has almost become the byword in motorcycle turbocharging. With good reason. The Santa Ana, California, based company has been connected with some of the most successful turbocharged machines and was instrumental in the production of the only complete turbocharged motorcycle offered for sale, the Kawasaki Z1R-TC.

ATP products are well proved in competition too. If you need an example of how a relatively light and simple turbocharged Kawasaki can run in top fuel drag racing, Pee Wee Gleason recently reached the Winston World Finals at Ontario Motor Speedway only to be beaten by the might of the monster supercharged Teson-Bernard XS1100 Yamaha.

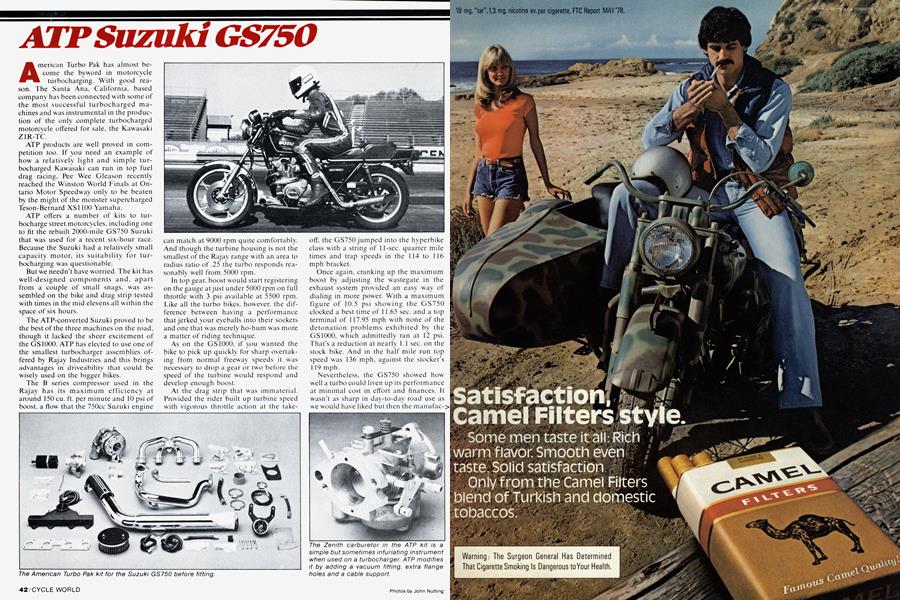

ATP offers a number of kits to turbocharge street motorcycles, including one to fit the rebuilt 2000-mile GS750 Suzuki that was used for a recent six-hour race. Because the Suzuki had a relatively small capacity motor, its suitability for turbocharging was questionable.

But we needn’t have worried. The kit has well-designed components and, apart from a couple of small snags, was assembled on the bike and drag strip tested with times in the mid elevens all within the space of six hours.

The ATP-converted Suzuki proved to be the best of the three machines on the road, though it lacked the sheer excitement of the GS1000. ATP has elected to use one of the smallest turbocharger assemblies offered by Rajay Industries and this brings advantages in driveability that could be wisely used on the bigger bikes.

The B series compressor used in the Rajay has its maximum efficiency at around 150 cu. ft. per minute and 10 psi of boost, a flow that the 750cc Suzuki engine can match at 9000 rpm quite comfortably. And though the turbine housing is not the smallest of the Rajay range with an area to radius ratio of .25 the turbo responds reasonably well from 5000 rpm.

In top gear, boost would start registering on the gauge at just under 5000 rpm on full throttle with 3 psi available at 5500 rpm. Like all the turbo bikes, however, the difference between having a performance that jerked your eyeballs into their sockets and one that was merely ho-hum was more a matter of riding technique.

As on the GS1000. if you wanted the bike to pick up quickly for sharp overtaking from normal freeway speeds it was necessary to drop a gear or two before the speed of the turbine would respond and develop enough boost.

At the drag strip that was immaterial. Provided the rider built up turbine speed with vigorous throttle action at the takeoff'. the GS750 jumped into the hyperbike class with a string of 11-sec. quarter mile times and trap speeds in the 114 to 116 mph bracket.

Once again, cranking up the maximum boost by adjusting the wastegate in the exhaust system provided an easy way of dialing in more power. With a maximum figure of 10.5 psi showing the GS750 clocked a best time of 11.65 sec. and a top terminal of 117.95 mph with none of the detonation problems exhibited by the GS1000. which admittedly ran at 12 psi. That’s a reduction at nearly 1.1 sec. on the stock bike. And in the half mile run top speed was 136 mph, against the Stocker’s 1 19 mph.

Nevertheless, the GS750 showed how well a turbo could liven up its performance at minimal cost in effort and finances. It wasn’t as sharp in day-to-day road use as we would have liked but then the manufac-> turers of turbo kits tend to sell maximum performance as opposed to usable performance where improvements in flexibility and torque at lower revs would provide more interesting results.

The ATP was the easiest kit to bolt on. The header pipes and inlet manifold are well-made with strong joint flanges and support the turbocharger with plenty of clearance above the gearbox. The waste gate sits unobtrusively in front of the generator cover with a small exhaust pipe tucked next to the frame.

The wastegate is unfortunately placed in a position that one of the mounting bolts is virtually impossible to tighten up once the exhaust system is installed. Silicone sealant is a real necessity here and as a precaution against leaks in the rest of the exhaust. Leaks mean no boost.

All the rubber pipework is by Weatherhead with screw fastenings that give a professional finish. The turbo has a onepiece bearing housing with a large lubrication feed from the engine’s pressure relief valve cover. Some difficulty was encountered when it was found that the cam chain tensioner assembly had to be removed to fit a machined block that replaces the original oil pressure relief valve cover and provides a restriction that ATP says increases the oil pressure to the turbo. The electrical terminal on the valve has to be trimmed to clear the tensioner spring. After assembly it was also noted that the countersunk holes for the two Allen screwheads had been drilled too deep, allowing the screws to bottom the threads and not pull down the block. The screws were trimmed to fit. Oil return from the turbo is by a large diameter pipe to a specially machined cap that screws into the original oil filler screw on the top of the clutch cover.

The boost gauge has a large diameter face and the needle is damped by filling the instrument with glycerin. Because the gauge must also fit Kawasakis, there wasn’t enough clearance between the back of the gauge and the Suzuki’s steering stem top nut. Several washers had to be packed under the longer bolts supplied for the handlebar clamps and this limited the engagement of the screws in the triple clamp threads.

Like the Magnum turbo kit, the ATP, having a Zenith carburetor, requires a fuel pump. The fuel pump offered is the same, an electric solid state Facet but with ATP’s decal on the side. A mounting plate is supplied for the pump and requires a hole drilled in a cross plate under the seat to support it. After using the machine for a couple of days and experiencing a flat battery, it was wondered if the extra load of the fuel pump on the electrical system (along with having the lights on all the time) might have been the straw that breaks the camel’s back. The current draw is only 0.6 amps for the pump, less than the taillight bulb.

Similar experiences with the Zenith carburetor on the GS750 as that found on the Magnum-kitted GS1000 suggest that fundamental changes in the type of carburetor used will be necessary if future turbocharged motorcycles are to experience wide appeal.

Without using the extra strong throttle return spring supplied in the kit to supplement the spring used on the carb body, we found it impossible to obtain a reliable idling speed. And puddling occurred when idling for a while that resulted in a rich mixture when pulling away from a standstill. One refinement on the carburetor was a vacuum fitting on the mounting flange that made the use of the Suzuki’s stock petcock (which is operated by vacuum) possible.

Most turbocharger kit manufacturers will claim that overall fuel consumption will remain much the same as the stock machine provided too much use of the turbo isn’t made. That’s like offering a gourmet meal to a guy and warning him that eating too much will make him fat.

We have to admit at having some fun with the GS750 turbo so we paid for that fun in gas and averaged 31.9 mpg.

The turbo kit supplied by ATP (251 East Stevens, Santa Ana, Calif. 92707) was the most expensive tried at $1295 but it was also the best of those offered. It could be assembled without problems by anyone with access to a file and the average tool kit.

The exhaust pipe has a fiberglass packed silencer but the machine emitted a similar but more muted burble than the GS1000. It did in fact register 93 db(A) on the sound meter using the CHP method of accelerating hard in second gear from 30 mph through 50 ft. with the meter 50 ft. away, perpendicular to the direction of travel. So on the latest bikes, the fitting of the turbo kit not only violates the statute book in many states but pushes the noise levels by over 11 db(A). Take heed.