SHOWDOWN FOR SHOCKS

Ten Aftermarket Competition Shocks Compared in the Lab and At Speed.

Shock absorber theory and practice has developed by leaps and bounds. Pun deliberate. Motocross racers one day discovered that increased wheel travel meant more speed with control, that is, winning. As the long-travel-rear (usually abbreviated LTR) suspension became routine practice, more and more off-road bikes appeared with shocks and springs set forward, cantilevered (lay-down), or both. Spring rates became more critical and shock bodies became longer. Suddenly there was room for improvement. There were ways to achieve more precise wheel control, to adapt for variations in terrain. Off-road motorcycles had more power, less weight and went faster over worse ground. For years shock absorbers were things to be replaced when they wore out. Now shocks are things you replace when something better comes along.

Now as then, bikes built for general sale arrived with shocks produced with a careful eye to cost. They were and are adequate, but seldom better than that. Changing to shocks from specialist firms, and to springs selected for each rider’s style and machine, has become one of the first steps in the enthusiast’s activities.

Making the choice is as difficult as it is popular. Most of the aftermarket shocks look pretty much alike. A shock absorber— they don’t absorb, by the way, they dampen—usually consists of a cylinder, a shaft and a piston, valves and seals. As the shaft moves the piston back and forth in the cylinder, oil must flow through the valves and orifices. The force required to do this slows the wheel and thus controls its motion and the motorcycle.

There must also be some space left inside the cylinder. If there was not, the oil would have no place to go as the shock was compressed. In the past, this space was filled with air. Air acts as a spring and its density varies with heat, so recently some makers have filled the space with an inert gas, nitrogen or freon, either in a separate bladder or under pressure. The latest extra is a reservoir, either attached to the cylinder or connected with a hose and mounted elsewhere, the theory being that the shock will be more stable and less prone to overheating.

The major area of difference in shocks is in valving and control.

All makers have things in common. They all have professional designers. They have limitations imposed by production requirements. They believe in their ideas. They hire professional riders and racers and listen to the report from the track and field.

And they all honestly believe in their products.

The enthusiast can appreciate this while puzzling over how to buy a good shock and the right spring. Some makers are big companies. Some are a few guys working on their own and depending on word of mouth. Some sponsor racing teams, in hopes success on the track will persuade fans that using what the team does will put them, too, in the winner’s circle. Through it all, impartiality is hard to come by.

Yes. A comparison test. Until now motorcyclists have had two fair-but-incomplete ways to judge a shock. There’s the lab, where we can find out in clear and exact ways what sort and degree of rebound and compression dampening has been provided in a shock, at a wide range of speeds and loads. The testing equipment can tell us how quickly a shock gets hot under load, and how much damping goes away as heat builds up. That’s half the story.

Testing shocks on the track or across the wilderness tells us what the motorcycle does with each shock fitted. A good rider with an analytical mind can feel and report on how the bike works, what the rear wheel is doing and (in some cases) why it’s doing what it does. So. The bike fan gets lots of figures; 20 lb. compression and 70 lb. rebound at 100 degrees F. A 10 percent loss at 250 degrees F. A stroke of four inches. Useful, but not enough.

Or the fan gets to read that Brand A is great, handles fine over the whoops. Entertaining, but again, not enough information when the fan will be spending $80 to $150 or more, in hopes of having a better motorcycle.

What we’ll do here is put the two parts together.

CYCLE WORLD has what we believe is the best and most complete suspension testing program going. We’ve been working in the lab, measuring and recording and observing, for more than a year. We’ve been riding oif-road for a collective century.

We reckoned it was time to compare shock absorbers. Put them through an expanded lab test, then take them into the field, on a production motorcycle which we knew well, and which was likely to be similar to the machines ridden by competi-> tion-oriented readers. Time to see how lab analysis and off-road testing relate.

There’s also a matter of motorcycle type and usage. We’ll begin this series with shocks for open-class racing motorcycles. Everything in this test will apply, with slight changes, to late-model serious enduro bikes. Subsequent comparisons will include dual-purpose and fun-type trails machines, then road and touring motorcycles.

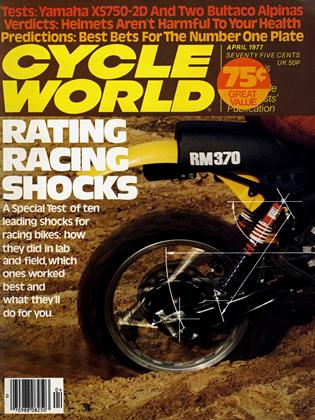

First step, acquiring test shocks. We wrote letters to the leading shock absorber makers. They were told that CYCLE WORLD planned a showdown for shocks. The test bike would be a Suzuki RM370A. Any company interested in taking part was asked to send three of their products. One for the lab, two for the bike. Model and spring rate were up to the makers. Send us, we invited, shocks which you’d sell over the counter to an RM370A owner who was racing the bike.

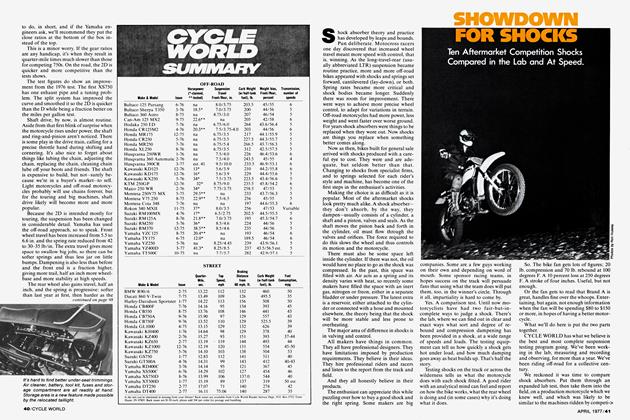

Ten manufacturers accepted. It was a pretty good range. Who they were (in alphabetical order) and what they sent, are listed below:

ARNACO LTR-1

Arnaco, Inc. 13431 Saticoy St. North Hollywood, Calif. 91605 Shock price: $109.95/pr. Spring price: 23.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The Arnaco is a single-wall design. Shock body and spring end are machined from billet aluminum. Internally, a pressurized damping fluid/nitrogen mixture is used in conjunction with a patented system of valving. Travel: 5.0in. (127mm) Pre-load adjustment: yes Piston rod diameter 0.562in. (14.3mm) Remarks: Includes a complete selection of spacers and hardware, and a Special tool for extremely easy preload adjustments.

Offered in 11-inch to 17-inch lengths, the shocks are designed for specific motorcycle applications.

KONI 23F-1034

Bikoni Ltd. 150 Green St. Hackensack, N.J. 07601 Shock price: $79.00/pr. Spring price: 24.00/pr. Rebuildable? no Construction: The Koni is a steel DeCarbon-type shock. Nitrogen, separated from the oil by a floating piston, is pressurized to 25 atmospheres (370 psi). Travel: 4.7in. (120mm) Pre-load adjustment: no* Piston rod diameter 0.380in. (9.65mm)

MARZOCCHI 400 F3

High Point 9604 Oates Drive Sacramento, Calif. 95827 Shock price: $110.00/pr. with springs.

Rebuildable? yes

Construction: The body with attached reservoir is cast aluminum, and contains an inner steel tube. Oil circulates between the body and tube, and through the reservoir. Compression displacement is taken up by a nitrogen filled bladder in the reservoir.

Travel: 5.5in. (140mm)

Pre-load adjustment: yes Piston rod diameter 0.472in. (12mm) Remarks: The shocks are factory charged with nitrogen at 28 psi. If necessary, compressed air may be used.

These shocks come equipped with Heim (swivel) bushings on the spring end.

In addition to rebuilding kits, accessory kits to tailor damping characteristics are also offered by the manufacturer.

Several damping rates are available for most applications.

Remarks: *When using dual-rate springs, no preload adjustment is possible. A camtype adjuster is provided for use with linear (single-rate) springs.

MICKEY THOMPSON 36-394-H3

Mickey Thompson 2701 E. Anaheim St.

Wilmington, Calif. 90744 Shock price: $99.50/pr.

Spring price: approx. 10.00/pr. Rebuildable? no

Construction: The Mickey Thompson shock is a DeCarbon type and locates the separator piston within the external reservoir. The shock body and reservoir are single tubes, connected by a finned casting.

Travel: 4.75in. (120mm)

Pre-load adjustment: yes Piston rod diameter 0.410in. (10.4mm) Remarks: These shocks were tested with optional Heim (swivel) ends, which are available for an additional $5.00pr.

Four damping rates are available, from H1 (soft) to H4 (hard).

Mickey Thompson also offers a remote reservoir shock. At press time, however, it was not available in the 151/2-inch length.

MOTO-X FOX 38-1426

Moto-X Fox 520 McGlincy Ln. Campbell, Calif. 95008 Shock price: $99.00/pr. Spring price: 21.95/pr. Reservoir: 50.00/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The basic shock has a single-wall steel cylinder and contains a gas/oil mix, although compressed air may be used instead. A remote reservoir is optional. The test shocks were firm; the maker also stocks soft and medium versions of this model. Travel: 5.25in. (133mm) Pre-load adjustment: no* Piston rod diameter 0.5in. (12.7mm) Remarks: Reservoir installation is simple and straight forward, although the factory will do it for an extra $10. The buyer can also get a kit to change damping rates. *Two spring retainer positions are provided to accommodate different length springs.

MULHOLLAND LTG 150C

Mulholland (Interpart) 230 W. Rosecrans Ave. Gardena, Calif. 90248 Shock price: $89.95/pr. Spring price: 27.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The shock body is a steel dual-wall design. Gas is contained within a bladder located between the inner and outer walls. A finned aluminum heat sink is fitted to the lower body for additional cooling. Travel: 5.0in. (127mm) Pre-load adjustment: no Piston rod diameter 0.482in. (12.25mm) Remarks: The LTG series shock is available in two damping rates.

In addition to rebuilding kits, replace ment components may be purchased which allow damping rates to be changed by the user.

Number One Products FP3941-H

Number One Products 4931 N. Encinita Ave. Temple City, Calif. 91780 Shock price: $69.95/pr. Spring price: 24.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: Number One shocks have steel bodies, and are dual-wall construction. A bladder filled with freon gas is located between the inner and outer walls for compression displacement. An aluminum coolor is provided for heat dissipation.

Travel: 5.25in. (133mm) Pre-load adjustment: yes Piston rod diameter 0.492in. (12.5mm) Remarks: Shocks can be ordered in three damping rates: soft, medium or firm. We tested the firm pair. Besides offering rebuilding kits, the factory makes available components for altering original damping rates.

RED WING G-390-85 (medium)

Marubeni America 200 Park Ave., New York, N.Y. 10017 Shock price: $61.90/pr. Spring price: 27.95/pr. Rebuildable? no Construction: The Red Wing is a steel body single-tube DeCarbon type shock. Nitrogen gas, at 18 atmospheres (265 psi), is segregated from the oil by the floating piston. Travel: 4.75in. (120mm) Pre-load adjustment: no Piston rod diameter 0.488in. (12.4mm) Remarks: Damping is available in three rates: soft, medium, and hard.

As testea, the Shocks were equipped with dual-rate 75/240 springs. These springs will not be available in the near future. An alternate (probably 90/160) rate spring must be used.

S&W LL525-10 (medium)

S&W Engineered Products 2617 Woodland Anaheim, Calif. 92801 Shock price: $69.90/pr. Spring price: 18.66/pr. Rebuildable: no Construction: S&W shocks are steel dou-> ble-wall units. They utilize a freon-filled nylon cell located in the cavity between inner and outer walls for compression displacement.

Travel: 5.5in.* (140mm)

Pre-load adjustment: yes Piston rod diameter 0.488in. (12.4mm) Remarks: Shocks are available in three damping rates for this application: “L”— soft, “LL”—medium, and “LLL”—hard.

S&W’s 1976 model shocks were used for this test. An improved 1977 version should be currently available.

"Because of the long shock stroke, a pair of S&W travel limiters is used on this bike.

WORKS PERFORMANCE

Works Performance Products 20970 Knapp St. Chatsworth, Calif. 91311 Shock price: $139.95/pr. with springs. Rebuildable? yes Construction: Works Performance shocks utilize a steel single-wall body, upon which is cast a finned aluminum heat sink/top mount. Compression displacement is handled by the nitrogen/oil mixture, charged to 250 psi. Travel: 4.5in. (114mm) Pre-load adjustment: no Piston rod diameter 0.500in. (12.7mm) Remarks: Works Performance shocks are not listed by model numbers. Instead, motorcycle model and use and rider weight should be given. The proper shock will then be supplied. Shocks can also be custom built for a particular need.

Along with the acceptances came some surprises. These firms are proud of their products. Several were a bit cautious. Their test programs differ from our program. They asked to be allowed to watch, to make suggestions and even to parcel out some of the testing.

We had nothing to hide, although we don’t enjoy strangers watching us work. It was agreed that the shock testing would be done at Number One Products, the spring testing at Mulholland and that observers would be allowed at the field trials.

TEST PROCEDURES

The theory behind the lab test procedures can become quite complicated. The multiplicity of numbers and graphs is staggering. But it ain't really all that hard to understand.

After all the basic facts (measurements, physical configuration, etc.) were compiled, the lab analysis began. Replicated for each shock, the procedure went like this: Each shock was mounted on the dynomometer. and its stroke (travel) was measured. The shock was then cycled on the dyno until 100 deg. F. was reached. This was to be the reference temperature at which all tests would be started.

Now the damping rates could be measured. Each shock was cycled at three speeds: slow (4.7 inch/sec.), medium (9.4 inch/sec), and fast (18.8 inch/sec.). The damping rates were recorded for each speed. Rates are reflected graphically, in the first set of curves for each shock. The larger the curves, the higher (stiffer) the damping rates.

The peak numerical readings for each speed are also given in the damping/ spring rate chart. Since all the tests were conducted in exactly the same manner, the damping rates for each shock can be directly compared to any other. Additionally, the medium velocity (9.4 in./sec.) is the same as we have been using for previous CYCLE WORLD shock dyno tests. So this portion of the test can be compared to the stock shocks we have previously tested.

The relative rates at 100 deg. F. provide a good basis for comparison, but more data is needed. To measure the effects of heat, each shock was run at the high speed for five minutes. A sensor affixed to the shock monitored the external temperature. Using 100 deg. F. as a reference, the damping fade, in percent was measured at 2.5 and 5 minute intervals. The temperature curves and damping fade are shown on the second graph.

The actual numerical rates at this temperature are shown in the damping chart. Cold and hot damping figures should indicate a shock's performance and stability under extreme conditions. But several factors must be considered when interpreting these figures:

Heat generated by a shock is a direct result of damping. If identically constructed shocks have different damping rates, the one with higher rates will get hotter faster. A shock with an extremely low damping rate could run all day long and just get warm. One with several hundred pounds damping force might blister paint in three minutes.

Single-wall, single-tube shocks transfer heat very quickly to the outside of the body. The temperature curves reflect that fact.

What the temperature curves do not show is that this enables the shocks to dissipate this heat to the air more quickly. Direct comparisons between shocks of different constructions then, are not truly representative. Field performance remains to be the most valid measurement of fade resistance, as well as general shock characteristics.

For the moment, most of these lab test figures should be considered as just figures. They show how the shock has been designed and valved.

The only conclusion to be drawn at this point is a general one. The springs proved to have test ratings quite close to their claimed ratings, close enough that we’d say the buyer can assume the springs he orders will be the springs he gets.

Even the testers were cautious not to check into the lab results, because we didn’t wish to have the performance checks influenced.

THE FIELD TESTS

Off-road racing bikes run on tracks or across the country. A motocross course can be duplicated in the desert while the desert cannot be duplicated at the track, so we laid out a desert test. Two loops, totaling about six miles, with jumps and a tour of a deep sand wash, a top-gear dash across the flats, wide open. (70-75 mph with stock gearing) and a run into the foothills, across whoop-de-doos and up and down some steep hills strewn with rocks. A challenge.

Riders vary. To allow' for this we had two riders; a 175-lb. expert desert racer and a 150-lb. novice, a man who has been riding on the road for years and off the road for a few months.

For fairness both men were ordered away from the test bike and the work area. Neither was allowed to know which shocks w'ere being used, just to be sure no personal feelings or past experience or reputations interfered. When the rider was allowed to approach the bike, the shocks were covered with a blanket, honest, and the blanket wasn't removed until the tester was in place.

The instructions were simple; Ride as fast and hard as good sense allows and report how the rear wheel is acting and how the bike responds through the various sections.

Present were the usual CYCLE WORLD crew plus representatives from four manufacturers: Arnaco, Mulholland, Koni and S&W.

(We had some reservations about this. They were unfounded. The reps didn't interfere with us or with each other. Instead. they pitched in and helped swap sets of shocks, oil the chain, top oft' the Suzuki’s tank. etc. This was a long, busy day and we couldn't have done it without them.)

Now, a few words of caution. The nature of a comparative test imposes some problems. The first set tested must be judged for itself. The second set has another measure, the third set has two and so it goes. There’s bound to be some influence. It can’t be kept out, so we’ll allow for it, by listing the rider comments in sequence.

The first set tested was the set on the bike, the Fox shocks. They were there because we used them for the color photography and we did that because they had the brightest colors. After that we tried the sets provided by firms whose people were present, then we picked sets out of the box, at random.

RIDER REACTIONS

FOX

Expert: “Overall, they’re very stiff. There’s too much compression damping. The bike corners exceptionally well and stays straight over the bumps. It won't throw you off but it could scare you a bit. I used the entire wheel travel on the gullies and washes, so the shock length is fine.”

Novice: “In general they're really stiff. On easy bumps, the rear wheel kicks; the bike is stable but stift'. The back hops up. high enough to bump you when you're standing up. I think the spring rate is too high and so is the initial damping. The shocks don’t begin to work until you hit a big bump really hard."

S&W

Expert: “The spring rate feels just right. The only flaw I found was when I was going really fast, the rear wheel skipped over small bumps. Not as good in the rough; the rear wheel didn't want to follow the ground. If these springs are progressive. they aren't progressive enough.

“Overall, they’re pretty good. I could go as fast as the (stock) front end would allow.”

Novice: “These are better. The rear wheel is on the ground more and there’s less pitch. But in a fast wash, the bike is maybe a bit less stable. Seems like a softer rate so they work better. There’s more control at lower speeds and the spring rate and damping seem more in proportion. (I may not be going fast enough).”

KONI

Expert: “The spring rate is okay, only because there’s too much compression damping. The back wheel is busy, although it’s always on the ground. I got a bit sideways twice. Coming up the rock hill it kicked crooked. Doesn't feel as it there’s a relief for sudden and hard impacts, then the wheel comes back out instead of having the impact slowed down. The bike stayed straight in the whoops, but it felt as if every bump in the course was fast and square.”

Novice: “I’m going faster and I may be using more shock. These seemed more compliant. They don’t work as well in the sand wash, the rear wheel didn’t track as well. The initial rate seemed lower and better for me. At speed they feel like the others, stiff, and they seemed touchier on rebound.”

MULHOLLAND

Expert: “These were pretty good although they kicked a bit hard. They're rough on initial impact, but once you get the wheel working, they feel fine. Good control. The rate and compression damping are perfect. I feel the bike using all the travel but it didn’t bottom and it went straight through the whoops and handled well in the corners. Other than that initial roughness, there's not a thing wrong with them.”

Novice: “They seemed to ride hard but with control. Best so far, although the rear is still too stiff. There’s more control in general, faster and more stable through the wash and straight off the jump. The springs feel progressive and it's not harsh on impact. Could they be shorter than the others?” (They weren’t.)

ARNACO

Expert: “I have mixed emotions. Feels like they want to work, then suddenly there's a kick in the back and you’re riding on the front wheel. I couldn’t pinpoint when it would happen. They swallowed the deep gullies and on the short ones, up she’d come. With the back kicking it was hard to go fast. Felt like the rear wheel was packing down, as if there was too little compression dampening and too much rebound and the wheel couldn’t return before it was pushed in some more. The rate’s okay, and it did follow the small bumps well.”

Novice: “There isn't enough of something and too much of something else. Felt like the rear of the bike was squatting down and not returning. The springs were fine, but it seemed as if there wasn't enough compression damping and the rebound was excessive. I had a hard time keeping it straight on a series of hops. Roll off the gas. fine. On the gas, more squat. First scare Fve had today.”

WORKS PERFORMANCE

Expert: “They’re perfect. Couldn’t get the bike to do a thing wrong. They’re stiff but that could be because they’re new. The rate’s fine. They did bottom—hard. They’re best in the corners. You could really blast into the turns, with full control the whole time.”

Novice: “I liked ’em. Ride’s hard, too stiff but they’re more compliant than the others. They felt like the third set. Predictable. No strange things. 1 can't tell if there’s anything different on braking. Compression and rebound are in proportion. I have nothing negative to say.”

MARZOCCHI

Expert: “Excellent. Below 50 mph, they’re the best yet. Above 50, the set before this was better. They already feel broken in. The rear kicked, but it was predictable. You could feel the rear wheel bottom if you hit a square ledge too fast. Above 50, you have to work a little. (The novice) will probably like these best.”

Novice: “The rate and damping are okay. On stutter bumps it snakes and won’t track. I could seem to go straight in the sand wash. I don’t think a hard rider would like these at all.”

(Note: As you may guess from the above, the two riders didn’t talk to each other until both had ridden each set and described their reactions.)

NUMBER ONE

Expert: “Too much damping. Through the whoops, they work, but on anything high or deep, they kick. Controllable and it wasn’t that sudden. On the rolling stuff they were fine and kept straight. 1 kept thinking the damping was too heavy and the bike wasn’t reacting quickly enough. Ed rate these fair: not bad, not good, fine as long as you don’t go too fast for too long.” Novice: “These feel at least as stiff as any we’ve tried so far. I couldn’t go as fast and they made the bike a little touchy. When either end bit, the other felt loose. May not be the shock, may just be wrong for me.”

ARNACO

KONI

MARZOCCHI

MICKEY THOMPSON

FOX

MULHOLLAND

NUMBER ONE

RED WING

S&W

WORKS PERFORMANCE

MICKEY THOMPSON

Expert: “Good, except the initial spring rate is too high and the initial bump is rough because of it. With other springs, they’d be as good as the other good ones. When you’re going really fast, everything’s perfect. The damping is right on.”

Novice: “I liked them. Good control, not as smooth as some, but predictable and the damping is in keeping with the overall stiffness. From low to high speed, they work really well. Stable at speed. Y’know, the more I learn about this, the less I have to say.”

RED WING

Expert: “Nothing wrong. They bottomed, but of course I have the course down now and I am going really fast.” (True, he was.) “They didn’t kick. They’re soft initially and the bike felt ready for anything. I’d say these are the best so far. The Red Wings are much better than the stock Rayabas.”

“What!? How the hell did you know what brand was on the bike?”

“They were so good I just had to stop and see what they were.”

Novice: “They felt just like the others. I couldn’t tell any difference between them and the previous set.”

That’s 10 sets. Along about with eighth test, the Arnaco guy came up to the test chief with a question: Could we try another set? He hadn’t asked the riders or looked at the notes. He could trust his eyes, though. The Arnaco shocks for Suzuki RMs come in different rates of damping. Would we try a set with different damping? A nice problem. It would break the rules. Nobody else had a chance to run two sets through the program. But, we were standing beneath the cold, gray sky that Saturday because we were testing shocks. If we had time, if all the others had been tested before dark, yeah, we'd run the second set.

And so it happened. It was nearly dark when the tenth set was done. We fitted the second Arnacos and the expert went for a loop. Being able to count, he knew what he was trying this time:

“1 liked them. They kicked a couple of times and the spike relief may need to be opened up a bit, but other than that, they’re as good as any in the group.”

(Later on the Arnaco man said the company had decided to standardize the damping of the second set and that would become the production model.)

So. We have tried 10 pair of aftermarket shocks and springs and we have learned . . . what?

CONCLUSIONS

Easy findings first. Progressive or dualrate springs are best for natural terrain. On the motocross course, you can pick the rate to get you safely over the worst jump on the track, but for cross-country work, having soft springs for regular ground and firm springs for the gullies and drops is the best way to go.

Next, there didn’t seem to be as much difference between the expert and the novice. No pattern. The fast man didn’t always like firm shocks and the slow one didn’t prefer soft ones. Folklore may have made too much of this for years.

We were especially pleased to see that both riders were consistent. Now it’s time to look at the earlier chart, the one with the lab results. The shocks which did best in the field, the Red Wing, Works Performance and Marzocchi, also turned out to be quite close to each other in damping rates, damping balance and spring rates.

Was there a winner? Not in the usual sense. Because there are no hard numbers, no lap times or scales of 1 to 10, we won’t say Brand A is the best in the bunch.

The rider comments, though, backed up by their ability to tell similar shocks from dissimilar shocks, do show a clear trend.

In the top group, we’ll put Marzocchi, Red Wing and Works Performance. Mickey Thompson and Mulholland are close after that, then we’ll let rider comments and lab figures speak for themselves.

Throughout all this, we have made no mention of price. Price is surely a factor. Soon as we all decide we want something, we ask, How Much?

The cost for each pair of shocks and springs to match are in that first list, with the specifications. The winner of this test and the choice of the buyer, then, becomes a matter of checking the field results, matching them to each rider’s style and budget, and buying what fits. Once again, the old rule: How fast do you want to spend?

Your type of motorcycle wasn’t mentioned? Consider all this Chapter One. Next, same tests, same desert, on playbikes. |5l