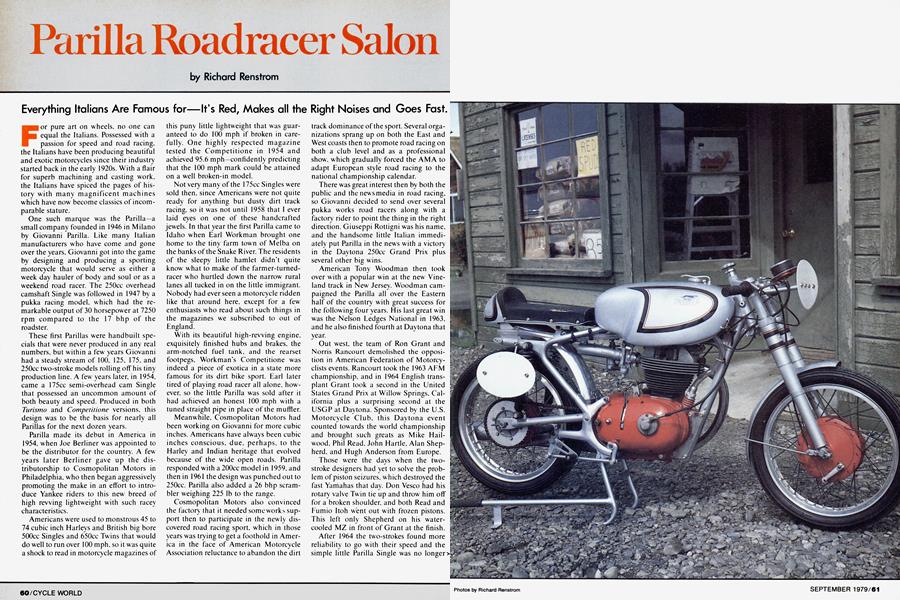

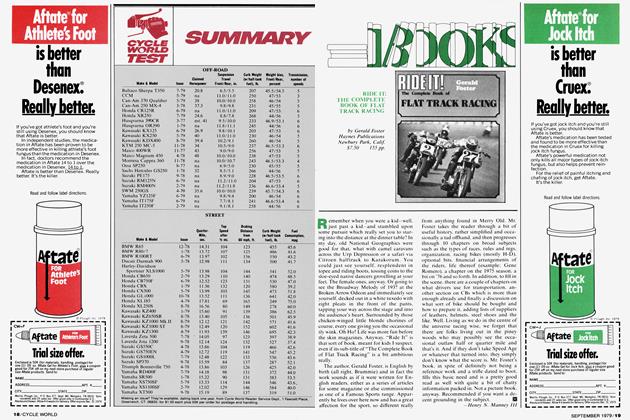

Parilla Roadracer Salon

Richard Renstrom

Everything Italians Are Famous for—It’s Red, Makes all the Right Noises and Goes Fast.

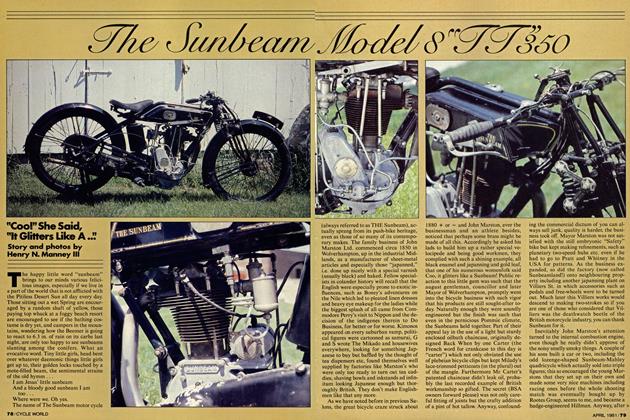

For pure art on wheels, no one can equal the Italians. Possessed with a passion for speed and road racing, the Italians have been producing beautiful and exotic motorcycles since their industry started back in the early 1920s. With a flair for superb machining and casting work, the Italians have spiced the pages of history with many magnificent machines which have now become classics of incomparable stature.

One such marque was the Parilia—a small company founded in 1946 in Milano by Giovanni Parilia. Like many Italian manufacturers who have come and gone over the years, Giovanni got into the game by designing and producing a sporting motorcycle that would serve as either a week day hauler of body and soul or as a weekend road racer. The 250cc overhead camshaft Single was followed in 1947 by a pukka racing model, which had the remarkable output of 30 horsepower at 7250 rpm compared to the 17 bhp of the roadster.

These first Parillas were handbuilt specials that were never produced in any real numbers, but within a few years Giovanni had a steady stream of 100, 125, 175, and 250cc two-stroke models rolling off his tiny production line. A few years later, in 1954, came a 175cc semi-overhead cam Single that possessed an uncommon amount of both beauty and speed. Produced in both Turismo and Competitione versions, this design was to be the basis for nearly all Parillas for the next dozen years.

Parilia made its debut in America in 1954, when Joe Berliner was appointed to be the distributor for the country. A few years later Berliner gave up the distributorship to Cosmopolitan Motors in Philadelphia, who then began aggressively promoting the make in an effort to introduce Yankee riders to this new breed of high revving lightweight with such racey characteristics.

Americans were used to monstrous 45 to 74 cubic inch Harleys and British big bore 500cc Singles and 650cc Twins that would do well to run over 100 mph, so it was quite a shock to read in motorcycle magazines of this puny little lightweight that was guaranteed to do 100 mph if broken in carefully. One highly respected magazine tested the Competitione in 1954 and achieved 95.6 mph—confidently predicting that the 100 mph mark could be attained on a well broken-in model.

Not very many of the 175cc Singles were sold then, since Americans were not quite ready for anything but dusty dirt track racing, so it was not until 1958 that I ever laid eyes on one of these handcrafted jewels. In that year the first Parilia came to Idaho when Earl Workman brought one home to the tiny farm town of Melba on the banks of the Snake River. The residents of the sleepy little hamlet didn’t quite know' what to make of the farmer-turnedracer who hurtled down the narrow rural lanes all tucked in on the little immigrant. Nobody had ever seen a motorcycle ridden like that around here, except for a few enthusiasts who read about such things in the magazines we subscribed to out of England.

With its beautiful high-revving engine, exquisitely finished hubs and brakes, the arm-notched fuel tank, and the rearset footpegs. Workman’s Competitione was indeed a piece of exotica in a state more famous for its dirt bike sport. Earl later tired of playing road racer all alone, however, so the little Parilia was sold after it had achieved an honest 100 mph with a tuned straight pipe in place of the muffler.

Meanwhile, Cosmopolitan Motors had been working on Giovanni for more cubic inches. Americans have always been cubic inches conscious, due, perhaps, to the Harley and Indian heritage that evolved because of the wide open roads. Parilia responded with a 200cc model in 1959, and then in 1961 the design was punched out to 250cc. Parilia also added a 26 bhp scrambler weighing 225 lb to the range.

Cosmopolitan Motors also convinced the factory that it needed some works support then to participate in the newly discovered road racing sport, which in those years was trying to get a foothold in America in the face of American Motorcycle Association reluctance to abandon the dirt track dominance of the sport. Several organizations sprang up on both the East and West coasts then to promote road racing on both a club level and as a professional show, which gradually forced the AMA to adapt European style road racing to the national championship calendar.

There was great interest then by both the public and the new s media in road racing, so Giovanni decided to send over several pukka works road racers along with a factory rider to point the thing in the right direction. Giuseppi Rottigni was his name, and the handsome little Italian immediately put Parilia in the news with a victory in the Daytona 250cc Grand Prix plus several other big wins.

American Tony Woodman then took over with a popular win at the new Vineland track in New Jersey. Woodman campaigned the Parilia all over the Eastern half of the country with great success for the following four years. His last great win was the Nelson Ledges National in 1963, and he also finished fourth at Daytona that year.

Out west, the team of Ron Grant and Norris Rancourt demolished the opposition in American Federation of Motorcyclists events. Rancourt took the 1963 AFM championship, and in 1964 English transplant Grant took a second in the United States Grand Prix at Willow Springs, California plus a surprising second at the USGP at Daytona. Sponsored by the U.S. Motorcycle Club, this Daytona event counted towards the world championship and brought such greats as Mike Hailwood, Phil Read, John Hartle, Alan Shepherd, and Hugh Anderson from Europe.

Those were the days when the twostroke designers had yet to solve the problem of piston seizures, w hich destroyed the fast Yamahas that day. Don Vesco had his rotary valve Twin tie up and throw him off for a broken shoulder, and both Read and Fumio Itoh went out with frozen pistons. This left only Shepherd on his watercooled MZ in front of Grant at the finish.

After 1964 the two-strokes found more reliability to go with their speed and the simple little Parilia Single was no longer* competitive. The tide had turned, and the era of two-stroke domination began. For the following few years the Yamahas fought it out with the four and six cylinder four-strokes, with the final four-stroke win occuring in 1969 when Australian Kel Carruthers took the world championship on the Benelli Four.

This was no climate for a lowly little Single to compete in, as the name of the game then was big bucks and lots of revs. This trend to two-strokes must have broken poor Giovanni’s heart; in 1967 he closed the doors of his little factory on the edge of Milano. His single-cylinder racers were no longer fast enough to win. and the roadsters’ temperamental starting habits made them non-competitive in an era of electric starter equipped multis from Japan.

There are, however, a few enthusiasts about who still appreciate the beauty, simple lines, superb machine work, and classic significance of a vintage road racer such as the Parilia. Earl Workman is one of these aficionados. He approached Cosmopolitan Motors way back in 1960 to ask if he could purchase a genuine road racing Parilia—the 250cc Super Sport. The answer was “no. only a few works racers were sent ’ over by the factory, and none are for sale.’’

Life often goes in circles, however, and in 1978 Workman heard Cosmopolitan had a badly rusted racer with many missing parts out in a shed and that Earl could have it for the princely sum of $150.

When the bike arrived it was even worse than Earl had imagined, but with many letters and hundreds of hours the Parilia was slowly brought back to its original condition. Only another restorer can appreciate the agony that goes into such a project. But when it was finished it was, indeed, a work of art.

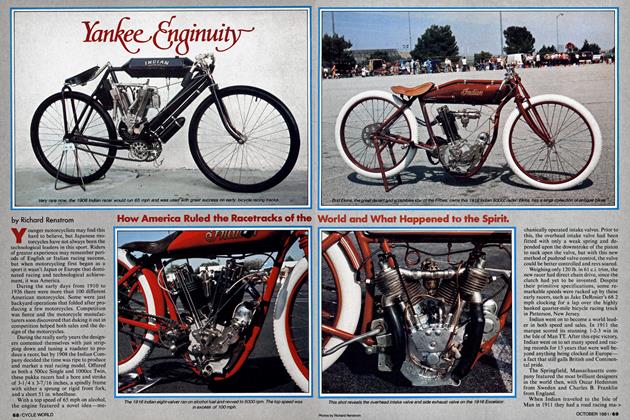

Workman’s Super Sport well represents the Italian concept of a racing Single of 1959. The Single has a bore and stroke of 68 x 68mm and runs on a full roller bearing lower end with a solid steel rod. The compression ratio is 10:1, and the carburetor is a Dell’Orto 30mm racing type with a remotely mounted float bowl to insulate the fuel from vibration.

The unique thing about the engine is the semi-overhead cam located in the very top of the timing case. Two very short pushrods work on rocker arms, thus keeping the valve gear weight to a minimum. On the production models a chain was used to drive the cam, but on this works bike a set of finely machined gears were used, all mounted on needle roller bearings.

Nobody can get Singles to rev like the Italians. Despite its fairly long stroke, the Parilia developed its 33-34 bhp at 10,000 rpm, which propelled the bike to 115 mph in unstreamlined form. Despite the revs, the engine was known as being nearly unburstable.

The gearbox is in unit behind the engine and has ratios of 6.42, 7.84, 10.50, and 15.18 to 1. The rearset shift linkage is typically Italian, as is the helical gear drive to the clutch. The tires are 2.50-18 in. front and 3.00-18 in. rear, while the alloy fullwidth hubs house l'/4 x 8 in. single leading shoe brakes. The Super Sport weighs only 235 lb., so the braking power is still impressive today.

The chassis is pure art. The frame is orthodox, as are the telescopic front forks, but the nearly 3 gal. steel fuel tank is a work of sculpture. A small racing seat, tachometer, number plates, and alloy rims are used, which combines with the long tapered magaphone that is also typically Italian.

The megaphone also contributes to the mystique of the bike. The sound starts out as a deep and authoritative bellow that turns into a scream of urgency as the revs mount. It is loud but tolerable and a contrast to the raspy, ear-splitting twostrokes of today. A nostalgic and vintage piece of music.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the Parilia is the color scheme. With its silver paint, black and red striping and decals, and the red engine castings and hubs, the Parilia has to be one of the most striking motorbikes ever built. It is this, more than anything else, that one remembers after having viewed the bike.

Beauty does not ensure success in the market place, however, so Giovanni Parilia was forced to close his doors in 1967. Beautiful and fast, the Parilia acquired a reputation for being temperamental in an age when motorcycles were becoming sophisticated and reliable.

Earl Workman doesn’t give a hoot about sophistication, however. All he thinks about when he points his vintage road racer off the bluff above the Snake River and down the winding road below is the beauty of the machine beneath him. Produced by craftsmen who were proud of their work, the Parilia Super Sport is the product of an age that has now slipped into the past. B8