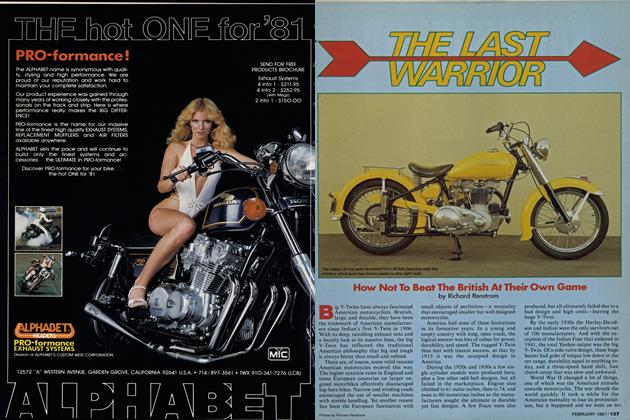

ED KRETZ and NO.38

It Took a Durable Combination to Win the First Daytona 200

Richard Renstrom

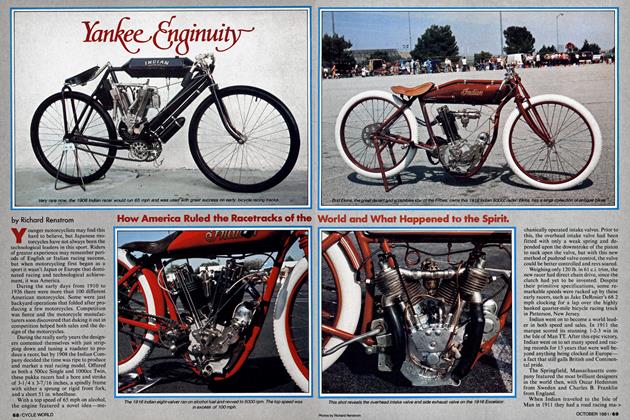

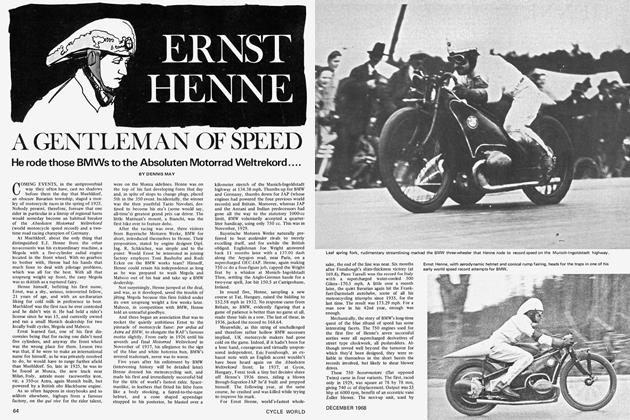

Every country has its great legends of speed. In England it is often the story of great TT races on the Isle of Man during the classic years of the 1930s, while in Italy it is usually the many great world championship wins by Moto Guzzi, Gilera. F. B. Mondial, and M. V. Agusta during the 1950s. The Irish like to talk about the legendary Stanley Woods, while the Germans point to the incredibly fast supercharged BMWs of the late 1930s.

In America we have the romantic board track days of the 1910 to 1926 era to talk about, plus the colorful post-World War II days when the British bikes came to challenge the Harleys and Indians.

For pure nostalgic appeal and aesthetic beauty it would, however, be hard to beat the story of Ed Kretz and his legendary Indian Sport Scout—a team that set the American scene on fire during the late 1930s and then again after the war until the early 1950s.

Kretz began his competition career when dollars came a lot harder than they do today. It was not until his early twenties that Kretz acquired any interest in motorcycles, at which time he purchased a worn out VL Harley-Davidson from the famous Floyd Clymer shop for $125. A short time later Ed observed a cinder track race, which enthused him so much that he returned to Clymer to purchase a used Rudge short track racer.

Kretz soon tired of the short track game and decided to strip down his old Harley for a bash at a race on the old Ascot fiveeighths mile dirt track. Despite having a non-competitive model compared to the many factory racers on hand then, Kretz rode like a wild man to finish second on a flat rear tire.

This remarkable performance was instantly recognized by Clymer, who quickly contacted the Indian Company in Springfield, Massachusetts to see if they would supply Kretz with a faster new machine for future events. The factory did, and Clymer then gave the promising young racer a job in his shop at the going rate of $18.50 per week. >

Ed then proceeded to gain a great deal of experience plus many wins in the rough and tumble local races, which encouraged him to enter the big 200 Mile National in 1936 at Savannah, Georgia. The 200 miler was called a road race, even though it was over a dirt track, since that is what an American road race consisted of then.

Kretz rode brilliantly that day to score a convincing 70.03 mph win—chopping 10 minutes off the record for the race and establishing himself as one of the fastest riders in the country.

The following year the American Motorcycling Association made a historic move to Daytona Beach, Florida for their 200 mile national, which started a legend of speed that has continued to this day. The original road course was not the smooth blacktop road circuit we know today, however, but a 3.2 mile long oval track that used the sand beach for one straight and a paved road for the other straight. The long straights ended in sharp, sandy corners, so that flat-out speeds and dirt tracking through the corners were both involved. In 1948 the course was increased to 4.1 miles, and then in 1964 the old beach course was thrown out in favor of the modern road racing circuit that is in use today.

The old beach course required a fast bike that would hold together for 200 full bore miles, and it also required a durable rider who could wrestle his bike through the deep sand corners that often broke up into deep ruts. The deep rutted corners loved to toss riders over handlebars, and especially late in the race when the rider’s arms were weary from the fight.

All of this suited Kretz perfectly, who had a powerful physique that packed 180 muscular pounds into a five foot eight inch frame. Despite his aggressive riding style. Kretz had a relaxed attitude that seemed to give him the edge in a really long race.

Kretz won this first Daytona Beach 200 Mile National in a convincing manner, which placed him right at the top of the American scene. He followed this up with more big national wins in the 1938, 1939, and 1940 Langhorne 100 Mile Championships over the one-mile track, the 1938 Laconia 200 Miler in New Hampshire, and the first of 14 Pacific Coast Championships he was destined to win. Kretz also loved the TT races over the undulating dirt tracks in California, where his wins came with monotonous regularity.

By then, Kretz was receiving top-flight factory support from Springfield, with his engines being supplied in batches of four to six at a time. Ed rode so hard that he had a difficult time keeping his motors in one piece, which was, perhaps, the subtle difference between Indian Scout speed and Harley-Davidson durability. Ed, for instance, led the Daytona classic on fourteen different occasions, yet he won only once, which makes one wonder just what might have happened if Indian had found the reliability to go with their speed.

Nicknamed the “iron man” because of his stamina, Kretz continued his winning ways after the war—taking 11 national races including the 1946 Laconia 100 Miler and the Langhorne classic in 1948. Ed also won a grueling 100 Mile TT National at Riverside, California in 1948, after which his hands were a bloody mess and he had to be lifted from his bike in a totally exhausted condition. That one, he now admits, was his toughest race!

Despite being 35 when racing resumed after the war, Kretz was at his peak and took big wins at Langhorne and Laconia— the only man ever to win both in one year. His last big win was the 100 Mile Championship at Carroll Speedway in Los Angeles, which Ed won in 1954 at the age of 43. Kretz continued to race for several more years, accumulating over 300 trophies.

Always a popular man with both his fans and his competitors, Kretz was awarded the Most Popular Rider trophy in both 1938 and 1948. In 1944 he opened his own Indian shop in Monterey Park on the edge of Los Angeles. In recent years BMW and Honda have been added, with Eddie Jr. managing the shop and Ed Sr. retiring.

During most of his career, Kretz rode the Sport Scout—a classic now held in the highest esteem by Indian afficionados the world over. In his early days Ed’s mount was the Scout 101, but this model was superceded by the faster Sport Scout in 1935 that went on to establish such a remarkable record both before and after World War II. The last great victories came in the early 1950s when Bobby Hill and Bill Turnan scored many national wins over the Harleys and the British bikes, only to fade from the scene after the company halted production of Indians in 1953.

Of all the illustrious old Indians, the Sport Scout is generally regarded as the best by those who study Indian history. Fast and agile in an era when American machines were becoming huge and clumsy, the Sport Scout must certainly be one of America’s all-time greats.

When Indian introduced the new 45 in 1935, it looked right, felt right, and was technically right. They went well and were durable. The new Scout was certainly the culmination of the design trend that had been underway in this country since the early 1920s when massive side-valve VTwins became the way to go.

The Sport Scout had a 45.44 cubic inch (750cc 42)°V-Twin engine with a bore and stroke of 2-% by 3-Vi inches. Long strokes were the vogue then, providing such incredible torque at low speeds, and this low speed power is what everyone wanted then. A short stroke engine would have been a disaster in the side-valve design, since flathead engines don’t breathe well enough to turn the really high revs that short strokes allow.

The cylinders and heads were of castiron, but alloy parts were optionally available. The pistons had a low 6 to 1 compression ratio, since a high dome on the piston would mask off the flow of gas to and from the side-mounted valves. Battery ignition was standard, but a Bosch or Splitdorf magneto was optionally available.

With its great torque, the engine had need for only a three speed gearbox, which had a hand shift and foot operated clutch pedal. The top gear ratio was 4.81 to 1, which provided an 80 mph top speed at around 5000 rpm.

With an emphasis on sporting use, the Scout had 4.00-18 tires instead of the 5.0016 inch size that Harley favored, with the seven inch brakes having only 25.5 sq. in. of surface area to haul down 436 lb. of snarling Scout. The frame was rigid, since it would be 1940 before Indian was to copy the European idea of a plunger rear suspension, while the girder fork up front had only about 3.5 in. of travel.

With the traditional fuel and oil tank combination that held 3.7 gal. of fuel and 2.5 qt. of oil, Indian continued an idea adopted in 1932 and returned the oil from the engine to the oil tank. In contrast, Harley just dumped oil on the ground.

With a wheelbase of 56.5 in. narrow sports fenders, solo seat, and a choice of colors (bright red was standard), the Sport Scout was a handsome machine.

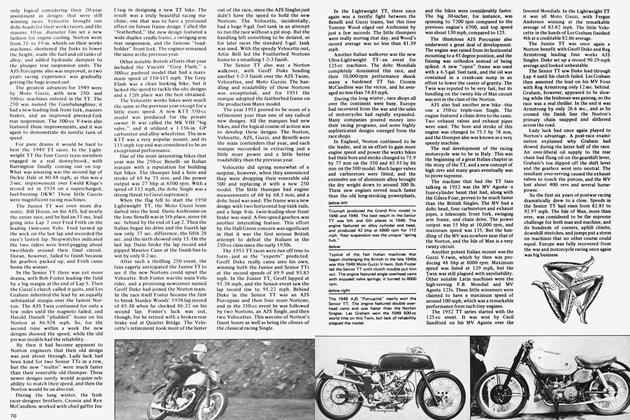

The famous Number 38 Scout that Kretz rode was, of course, somewhat different than the standard road model. A true works racer, Number 38 ran a whaleof-a-lot faster than the stocker—even if Indian advertising then led you to believe that these racers were “almost like the Indians you can buy”.

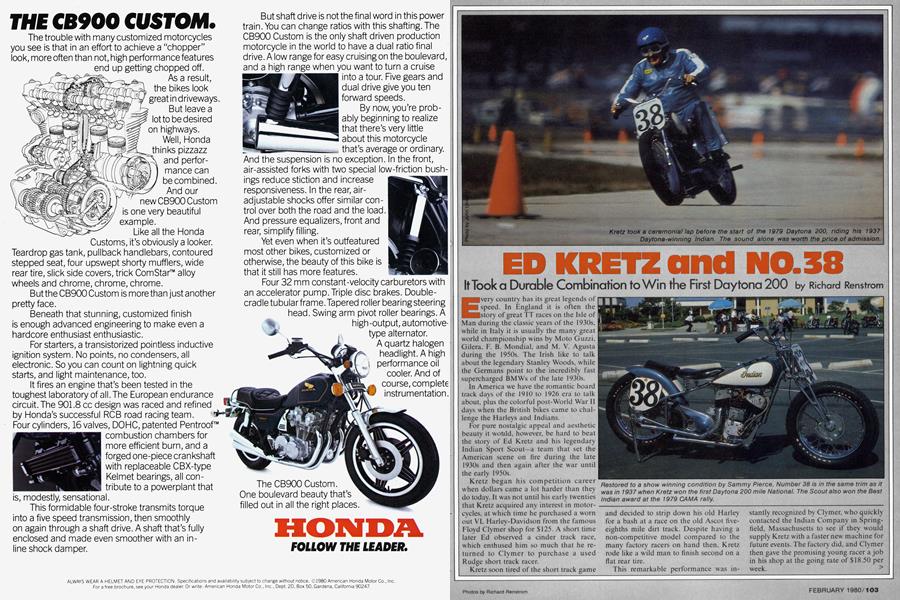

The beautifully restored Sport Scout shown is the work of Ed’s old tuner, Sammy Pierce, Sam is now more or less retired, but before he retired he sold and manufactured parts for the old Indians. Sam’s love for the art that flowed out of Springfield is also a legend, and it was his dedicated work that produced such the magnificently restored Number 38.

Authentically restored to 1937 Daytona winning specifications, the racer has a 6.5 to 1 compression ratio and a 1.5 in. Linkert carburetor. The heart and secret to making a flathead run is the cam, which is one of those mystical parts that silently flowed out of the race shop from time to time in an effort to beat the dreaded Harleys.

With a tuned straight pipe exhaust 30 in. long, larger valves, a magneto ignition, and ports polished like glass, old Number 38 produced 41 bhp at 6500 rpm. Kretz ran a 6.50 to 1 gear ratio for a one-half mile track, 4.74 for the mile, and 4.33 for the long straights of Daytona. This provided about 90 mph straightaway speeds on the half mile track, 105 on the mile, and 114 at Daytona. Ed, however, claims that the bike has clocked 121 mph, which means it was turning 6900 revs—a remarkable engine speed for a 1937 side-valve engine!

The chassis was quite standard on the Daytona Scout with a 56 in. wheelbase and standard fuel-oil tank. No front fender was used then, while the rear was bobbed and then fitted with a racing pillion seat. A set of 4.00 in. tires were used, but a 19 incher replaced the original 18 inch rim up front. The dry weight for Daytona was 360 lb., but for the flat tracks the brakes were dispensed with and a smaller tank fitted to drop the weight to a remarkable 310 lb.

Now 69, Kretz can look back on his career with great pride. He is especially fond of his epic win at Daytona in 1937 before 15,000 fans, a win which started such a rich tradition of speed on two wheels at that now famous place. Ed no longer performs before 15,000 fans, but when he exhibits his beautifully restored Daytona winner at rallies, a crowd always gathers to view the historic machine and meet the living legend.

Always a gentleman, Ed always takes the time to talk to anyone who inquires about him or his illustrous machine. Thoughtful and sincere, Kretz was and always will be the kind of man who deserves to be remembered with kindness by those who are concerned with where our sport has come from and where it is going.

Old number 38, meanwhile, is a magnificent classic from that unique American era between the depression and the 1950s when America discovered that side-valve engines were obsolete on the international scene. Designed and raced by men who were unconcerned about anything not produced in America, the 1937 Sport Scout is a monument to an engineering ideal that time was destined to doom to antiquity. E3