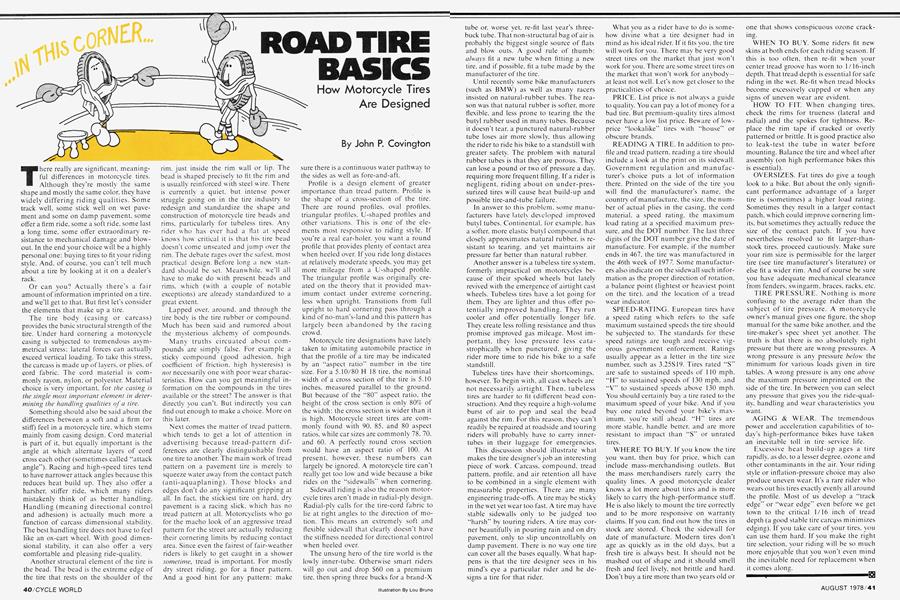

ROAD TIRE BASICS

How Motorcycle Tires Are Designed

John P. Covington

There really are significant, meaningful differences in motorcycle tires. Although they’re mostly the same shape and mostly the same color, they have widely differing riding qualities. Some track well, some stick well on wet pavement and some on damp pavement, some offer a firm ride, some a soft ride, some last a long time, some offer extraordinary resistance to mechanical damage and blowout. In the end your choice will be a highly personal one: buying tires to fit your riding style. And, of course, you can’t tell much about a tire by looking at it on a dealer's rack.

Or can you? Actually there’s a fair amount of information imprinted on a tire, and we’ll get to that. But first let’s consider the elements that make up a tire.

The tire body (casing or carcass) provides the basic structural strength of the tire. Under hard cornering a motorcycle casing is subjected to tremendous asymmetrical stress: lateral forces can actually exceed vertical loading. To take this stress, the carcass is made up of layers, or plies, of cord fabric. The cord material is commonly rayon, nylon, or polyester. Material choice is very important, for the casing is the single most important element in determining the handling qualities of a tire.

Something should also be said about the differences between a soft and a firm (or stiff) feel in a motorcycle tire, which stems mainly from casing design. Cord material is part of it, but equally important is the angle at which alternate layers of cord cross each other (sometimes called “attack angle”). Racing and high-speed tires tend to have narrower attack angles because this reduces heat build up. They also offer a harsher, stiffer ride, which many riders mistakenly think of as better handling. Handling (meaning directional control and adhesion) is actually much more a function of carcass dimensional stability. The best handling tire does not have to feel like an ox-cart wheel. With good dimensional stability, it can also offer a very comfortable and pleasing ride-quality.

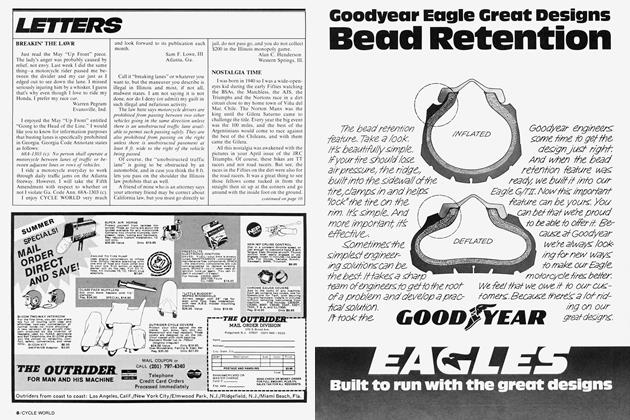

Another structural element of the tire is the bead. The bead is the extreme edge of the tire that rests on the shoulder of the rim. just inside the rim wall or lip. The bead is shaped precisely to fit the rim and is usually reinforced with steel wire. There is currently a quiet, but intense power struggle going on in the tire industry to redesign and standardize the shape and construction of motorcycle tire beads and rims, particularly for tubeless tires. Any rider who has ever had a fiat at speed knows how critical it is that his tire bead doesn't come unseated and jump over the rim. The debate rages over the safest, most practical design. Before long a new standard should be set. Meanwhile, we'll all have to make do with present beads and rims, which (with a couple of notable exceptions) are already standardized to a great extent.

Lapped over, around, and through the tire body is the tire rubber or compound. Much has been said and rumored about the mysterious alchemy of compounds.

Many truths circuated about compounds are simply false. For example a sticky compound (good adhesion, high coefficient of friction, high hysteresis) is not necessarily one with poor wear characteristics. How can you get meaningful information on the compounds in the tires available or the street? The answer is that directly you can’t. But indirectly you can find out enough to make a choice. More on this later.

Next comes the matter of tread pattern, which tends to get a lot of attention in advertising because tread-pattern differences are clearly distinguishable from one tire to another. The main work of tread pattern on a pavement tire is merely to squeeze water away from the contact patch (anti-aquaplaning). Those blocks and edges don’t do any significant gripping at all. In fact, the stickiest tire on hard, dry pavement is a racing slick, which has no tread pattern at all. Motorcyclists who go for the macho look of an aggressive tread pattern for the street are actually reducing their cornering limits by reducing contact area. Since even the fairest of fair-weather riders is likely to get caught in a shower sometime, tread is important. For mostly dry street riding, go for a finer pattern. And a good hint for any pattern: make sure there is a continuous water pathway to the sides as well as fore-and-aft.

Profile is a design element of greater importance than tread pattern. Profile is the shape of a cross-section of the tire. There are round profiles, oval profiles, triangular profiles. U-shaped profiles and other variations. This is one of the elements most responsive to riding style. If you’re a real ear-holer, you want a round profile that provides plenty of contact area when heeled over. If you ride long distaces at relatively moderate speeds, you may get more mileage from a U-shaped profile. The triangular profile was originally created on the theory that it provided maximum contact under extreme cornering, less when upright. Transitions from full upright to hard cornering pass through a kind of no-man’s-land and this pattern has largely been abandoned by the racing crowd.

Motorcycle tire designations have lately taken to imitating automobile practice in that the profile of a tire may be indicated by an “aspect ratio” number in the tire size. For a 5.10/80 H 18 tire, the nominal width of a cross section of the tire is 5.10 inches, measured parallel to the ground. But because of the “80” aspect ratio, the height of the cross section is only 80% of the width: the cross section is wider than it is high. Motorcycle street tires are commonly found with 90. 85, and 80 aspect ratios, while car sizes are commonly 78, 70. and 60. A perfectly round cross section would have an aspect ratio of 100. At present, however, these numbers can largely be ignored. A motorcycle tire can't really get too low and wide because a bike rides on the “sidewalls” when cornering.

Sidewall riding is also the reason motorcycle tires aren’t made in radial-ply design. Radial-ply calls for the tire-cord fabric to lie at right angles to the direction of motion. This means an extremely soft and flexible sidewall that clearly doesn't have the stiffness needed for directional control when heeled over.

The unsung hero of the tire world is the lowly inner-tube. Otherwise smart riders will go out and drop $60 on a premium tire, then spring three bucks for a brand-X tube or. worse yet, re-fit last year’s threebuck tube. That non-structural bag of air is probably the biggest single source of flats and blow outs. A good rule of thumb: always lit a new tube when fitting a new tire, and if possible, fit a tube made by the manufacturer of the tire.

Until recently some bike manufacturers (such as BMW) as well as many racers insisted on natural-rubber tubes. The reason was that natural rubber is softer, more flexible, and less prone to tearing the the butyl rubber used in many tubes. Because it doesn’t tear, a punctured natural-rubber tube loses air more slowly, thus allowing the rider to ride his bike to a standstill with greater safety. The problem with natural rubber tubes is that they are porous. They can lose a pound or two of pressure a day, requiring more frequent filling. If a rider is negligent, riding about on under-pressurized tires will cause heat build-up and possible tire-and-tube failure.

In answer to this problem, some manufacturers have latelv developed improved butyl tubes. Continental, for example, has a softer, more elastic butyl compound that closely approximates natural rubber, is resistant to tearing, and yet maintains air pressure far better than natural rubber.

Another answer is a tubeless tire system, formerly impractical on motorcycles because of their spoked wheels but lately revived with the emergence of airtight cast wheels. Tubeless tires have a lot going for them. They are lighter and thus offer potentially improved handling. They run cooler and offer potentially longer life. They create less rolling resistance and thus promise improved gas mileage. Most important. they lose pressure less catastrophically when punctured, giving the rider more time to ride his bike to a safe standstill.

Tubeless tires have their shortcomings, however. To begin with, all cast wheels are not necessarily airtight. Then, tubeless tires are harder to fit (different bead construction). And they require a high-volume burst of air to pop and seal the bead against the rim. For this reason, they can’t readily be repaired at roadside and touring riders will probably have to carry innertubes in their luggage for emergencies.

This discussion should illustrate what makes the tire designer's job an interesting piece of w'ork. Carcass, compound, tread pattern, profile, and air retention all have to be combined in a single element with measurable properties. There are many engineering trade-offs. A tire may be sticky in the wet yet wear too fast. A tire may have stable sidewalls only to be judged too “harsh” by touring riders. A tire may corner beautifully in pouring rain and on dry pavement, only to slip uncontrollably on damp pavement. There is no way one tire can cover all the bases equally. What happens is that the tire designer sees in his mind’s eye a particular rider and he designs a tire for that rider.

What you as a rider have to do is somehow divine what a tire designer had in mind as his ideal rider. If it fits you. the tire will work for you. There may be very good street tires on the market that just won’t work for you. There are some street tires on the market that won’t work for anybody— at least not well. Let’s now get closer to the practicalities of choice.

PRICE. List price is not always a guide to quality. You can pay a lot of money for a bad tire. But premium-quality tires almost never have a low list price. Beware of low'price “lookalike” tires with “house” or obscure brands.

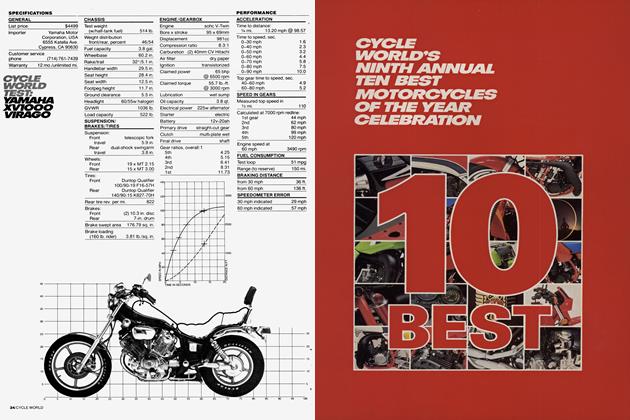

READING A TIRE. In addition to profile and tread pattern, reading a tire should include a look at the print on its sidewall. Government regulation and manufacturer’s choice puts a lot of information there. Printed on the side of the tire you will find the manufacturer’s name, the country of manufacture, the size, the number of actual plies in the casing, the cord material, a speed rating, the maximum load rating at a specified maximum pressure. and the DOT number. The last three digits of the DOT number give the date of manufacture. For example, if the number ends in 467, the tire was manufactured in the 46th week of 197 7. Some manufacturers also indicate on the sidewall such information as the proper direction of rotation, a balance point (lightest or heaviest point on the tire), and the location of a tread wear indicator.

SPEED-RATING. European tires have a speed rating which refers to the safe maximum sustained speeds the tire should be subjected to. The standards for these speed ratings are tough and receive vigorous government enforcement. Ratings usually appear as a letter in the tire size number, such as 3.25S19. Tires rated “S” are safe to sustained speeds of 110 mph. “El” to sustained speeds of 130 mph. and “V” to sustained speeds above 130 mph. You should certainly buy a tire rated to the maximum speed of your bike. And if you buy one rated beyond your bike's maximum. you’re still ahead. “H” tires are more stable, handle better, and are more resistant to impact than “S” or unrated tires.

WHERE TO BUY. If you know the tire you want, then buy for price, which can include mass-merchandising outlets. But the mass merchandisers rarely carry the quality lines. A good motorcycle dealer knows a lot more about tires and is more likely to carry the high-performance stuff. He is also likely to mount the tire correctly and to be more responsive on warranty claims. If you can. find out how' the tires in stock are stored. Check the sidewall for date of manufacture. Modern tires don’t age as quickly as in the old days, but a fresh tire is always best. It should not be mashed out of shape and it should smell fresh and feel lively, not brittle and hard. Don’t buy a tire more than two years old or one that show's conspicuous ozone cracking.

WHEN TO BUY. Some riders fit new skins at both ends for each riding season. If this is too often, then re-fit when your center tread groove has worn to 1/16-inch depth. That tread depth is essential for safe riding in the wet. Re-fit when tread blocks become excessively cupped or when any signs of uneven w'ear are evident.

HOW TO FIT. When changing tires, check the rims for trueness (lateral and radial) and the spokes for tightness. Replace the rim tape if cracked or overly patterned or brittle. It is good practice also to leak-test the tube in water before mounting. Balance the tire and wheel after assembly (on high performance bikes this is essential).

OVERSIZES. Fat tires do give a tough look to a bike. But about the only significant performance advantage of a larger tire is (sometimes) a higher load rating. Sometimes they result in a larger contact patch, w hich could improve cornering limits. but sometimes they actually reduce the size of the contact patch. If you have nevertheless resolved to fit larger-thanstock tires, proceed cautiously. Make sure your rim size is permissible for the larger tire (see tire manufacturer’s literature) or else fit a wider rim. And of course be sure you have adequate mechanical clearance from fenders, swingarm. braces, racks, etc.

TIRE PRESSURE. Nothing is more confusing to the average rider than the subject of tire pressure. A motorcycle owner’s manual gives one figure, the shop manual for the same bike another, and the tire-maker’s spec sheet yet another. The truth is that there is no absolutely right pressure but there are w'rong pressures. A wrong pressure is any pressure below the minimum for various loads given in tire tables. A wrong pressure is any one above the maximum pressure imprinted on the side of the tire. In between you can select any pressure that gives you the ride-quality. handling and wear characteristics you want.

AGING & WEAR. The tremendous power and acceleration capabilities of today's high-performance bikes have taken an inevitable toll in tire service life.

Excessive heat build-up ages a tire rapidly, as do, to a lesser degree, ozone and other contaminants in the air. Your riding style or inflation-pressure choice may also produce uneven wear. It's a rare rider who wears out his tires exactly evenly all around the profile. Most of us develop a “track edge” or “wear edge" even before we get town to the critical 1/16 inch of tread depth (a good stable tire carcass minimizes edging). If you take care of your tires, you can use them hard. If you make the right tire selection, your riding w ill be so much more enjoyable that you won't even mind the inevitable need for replacement when it comes along.