Clothing for Cold Weather Motorcycling

JOHN P. COVINGTON

HOW COLD CAN YOU GET on a motorcycle? Ask any winter rider and he will turn pale, mumble incoherently, and gradually assume an expression of unspeakable horror. He has learned the hard way that high wind and low temperature, coupled with low bodily activity, create an environment very unsympathetic to human existence, let alone comfort. Yet there are people who thrive under such conditions. Mountain climbers, high-altitude pilots, arctic explorers and others meet the challenge of the cold regularly and with relative immunity. Their knowledge can be valuable to the motorcyclist, giving him another season in which to enjoy the advantages of his machine.

Before selecting clothing for the cold, you should understand that the body produces heat in much the same manner as a motorcycle — by oxidizing fuel. It uses this heat to maintain optimum temperature for its various processes. Because the heat produced flows through the body and out into the environment, production must be continuous. When you begin to get cold, your body is transferring more heat to the environment than it is generating. When you get hot. it's the other way around.

Since the body is cleverly engineered for self-preservation, it has certain means for maintaining the optimum temperature. One of these is changing the rate of heat transfer by blood circulation and perspiration. When the body gets too hot. the flow of warm blood to the skin and extremities is increased. Your arms anil legs act as radiators from which the heat can be quickly transferred to the air. Conversely, when the body begins to get cold, it reduces the peripheral blood supply. Thus your hands anil feet, even though warmly insulated, will get cold when your body heat is low.

Perspiration, the other means of varying heat transfer, is very effective, but it creates problems for the clothing designer. Evaporation absorbs heat, a fact that the body uses to advantage when perspiring. Most of this perspiration occurs as unnoticed water vapor, a continuous process that accounts for about 25c/< of the body's total heat loss. But when the temperature rises, perspiration increases to the point of sw-eating. This dampens insulation materials which then lose their efficiency. In subzero climates where life itself is at stake, men are very careful to avoid sweating. Nervous tension also causes sweating (on palms, armpits and soles of feet) and acts against the body's careful heat balance. If you must ride a competition event in the cold, stay cool. man.

Although varying the rate of heat loss helps, the body has a much more flexible means of temperature control: It can simply increase heat production. The catch is that heat generation depends

on muscular activity, on the amount of work the body is doing. And none of us can devote his work solely to the interests of keeping warm. A sitting-resting man produces about 50 kilocalories per square meter of skin surface per hour (which we will call a metabolic heat rate of one. or I M). A man at hard physical labor can produce up to ten times this amount. Other activities range between these values: a touring motorcyclist generates about 1.5 M anil an enduro rider, about 6M. Violent shivering generates up to 3M. These figures, as we shall see. are critical for determining how much clothing should be worn in the cold.

In spite of its clever engineering, the body needs assistance to exist on earth. The lowest temperature that a resting, unclothed man could endure indefinitely is 63 (with shivering. 36 ). For lower temperatures he adds insulation to slow down the heat escaping into the environment.

I his heat flow will be proportional to the conductivity of the insulating material and to the difference in temperatures from one side to the other. It will be inversely proportional to the thickness of the insulating material. To keep warm, we look for material of lowest conductivity and use it thick enough to preserve the steadywarmth.

l or practical purposes, the most efficient insulation is "dead air space." Any of the common clothing fillers provide this by trapping air into small compartments where heat transfer by air movement (convection) is negligible. For a given thickness, all fillers (cotton, wool, dacron and down) offer equal insulation, but some have certain mechanical advantages over others. Word, when it gets damp, retains its loft better than cotton and thus its insulating value. Goose down, the most expensive filler, is the lightest for a given thickness and is highly permeable to watei vapor. Also, down garments arc so fluffy that they do not restrict movement. The important thing to remember for any of these materials is that insulating value depends on thickness.

Almost everyone but the motorcyclist has one more layer of insulation. This is the thin sheath of air (thermal boundary layer) immediately surrounding the body. In still air. it is equivalent to about 1/4 inch of clothing. But as we all know, the motorcyclist is never in still air. Besides normal convective currents and drift velocities. he faces the wind caused by the motion of his machine. The result is disastrous to the conservation of heat.

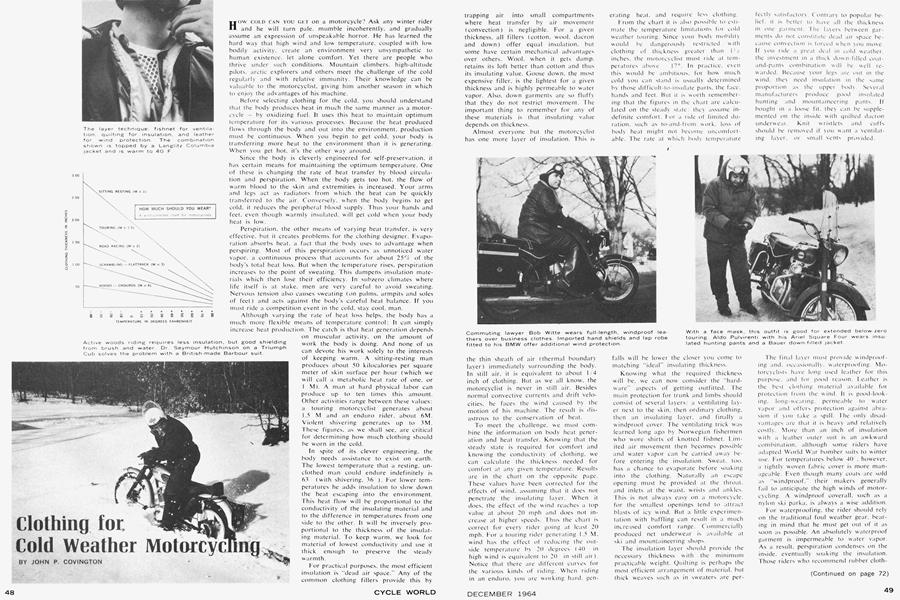

To meet the challenge, we must combine the information on body heat generation anti heat transfer. Knowing that the steady state is required for comfort and knowing the conductivity of clothing, we can calculate the thickness needed for comfort at any given temperature. Results are in the chart on the opposite page. These values have been corrected for the effects of wind, assuming that it does not penetrate the insulating layer. When it does, the effect of the wind reaches a top value at about 20 mph and does not increase at higher speeds. Thus the chart is correct for every rider going at least 20 mph. For a touring rider generating 1.5 M. wind has the effect of reducing the outside temperature by 20 degrees (40 in high wind is equivalent to 20 in still air). Notice that there are different curves tor the various kinds of riding. When riding in an enduro, you are working hard, generating heat, and require less clothing.

From the chart it is also possible 10 estimate the temperature limitations tor cold weather touring. Since vom body mobility would be dangerously restricted with clothing of thickness greater than 11 : inches, the motorcyclist must ride at tempel atures above 17°. In practice, even this would be ambitious, for how much cold you can stand is usually determined by those difficnlt-to-insulate parts, the face, hands and feet. But it is worth remembering that the figures in the chart are calculated on the steady state: they assume indefinite comfort. I or a ride of limited duration. such as to-and-from work, loss of hotly heat might not become uncomfortable. The rate at which body temperature

falls will be lower the closer you come to matching "ideal" insulating thickness.

Knowing what the required thickness will be. we can now consider the "hardware" aspects of getting outfitted. I he main protection for trunk and limbs should consist of several layers: a ventilating layer next to the skin, then ordinary clothing, then an insulating layer, and finally a windproof cover. The ventilating trick was learned long ago by Norwegian fishermen who wore shirts of knotted fishnet. Limited air movement then becomes possible and water vapor can be carried away before entering the insulation. Sweat, too. has a chance to evaporate before soaking into the clothing. Naturally an escape opening must be provided at the throat, and inlets at the waist, wrists and ankles.

I his is not always easy on a motorcycle, for the smallest openings tend to attract blasts of icy wind. But a little experimentation with baffling can result in a much increased comfort range. Commercially produced net underwear is available at ski and mountaineering shops.

The insulation layer should provide the necessary thickness with the minimum practicable weight. Quilting is perhaps the most efficient arrangement of material, but thick weaves such as in sweaters are perteel I y satisfactory (. ontrary to popular belief. it is belter to have all the thickness in one garment. I he layers between garments tit) not constitute dead air space because convection is torced when vou move. It you title a great deal in cold weather, the investment in a thick down-filled coatand-pants combination will be well rewarded. Because your legs ate out in the wind, they need insulation in the same proportion as the uppei body. Several manufacturers produce good insulated hunting and mountaineering pants. If bought in a loose fit. they can be supplemented on the inside with quilted dacron underwent. Knit wristlets and cuffs should be removed if you want a ventilating layer, or small vents provided.

I he final layer must provide w indproofing and. occasionally, waterproofing. Motorcyclists have long used leather for this purpose, and for good reason, l eather is the best clothing material available fot protection from the wind. It is good-looking. long-wearing, permeable to water vapor and offers protection against abrasion if you take a spill. I he only disadvantages are that it is heavy and relatively costly. More than an inch of insulation with a leather outer suit is an awkward combination, although some riders have adapted World War bomber suits to winter use. For temperatures below 40 . however, a tightly woven fabric cover is more manageable. Even though many coats are sold as "windproof." their makers generally fail to anticipate the high winds of motorcycling. A windproof coverall, such as a nylon ski parka, is always a wise addition.

For waterproofing, the rider should rely on the traditional foul weather gear, bearing in mind that he must get out of it as soon as possible. An absolutely waterproof garment is impermeable to water vapor. As a result, perspiration condenses on the inside, eventually soaking the insulation. Those riders who recommend rubber clothing for cold-weather wear have noticed its windproofing qualities. A touring rider produces relatively little perspiration and can remain comfortable in rainwear for several hours. In the long run. however, the thermal advantage will be more than reversed.

(Contmued on page 72)

To the cold weather competition rider, outfitting is a different proposition. Because of his activity, he needs much less insulation. But in addition to rain and wind, he must protect himself against mud. streams, brush and other hazards. The European style riding suit, such as the Barbour suit, is excellent for this. It is made of tough, waterproof fabric and can be adjusted for a close fit at the ankles, wrists and waist. Insulation can be added underneath in any thickness required. Numerous pockets provide for necessary items such as maps, route sheets, tire gauge, etc. Because these suits do offer some degree of vapor permeability, they are also worn by many touring riders.

Headwear for the winter rider is virtually the same whatever his style of riding. Modern science has given us crash helmets, and the likelihood of ice makes them all the more sensible in the cold. Good helmets are about an inch thick, lined with a cellular material of low thermal conductivity. The full-jet stvlc offers the most protection, but many of the touring models can be fitted with winter adapters to cover the ears and neck.

Hace protection is an equally important but little understood matter. T he chief reason for covering the face is not so much for /Vs comfort, but for over-all comfort. When your face is exposed to the cold, the body protects it by increasing its supply of warm blood. This keeps the skin temperature to a tolerable level, but the exposure is expensive. Your face becomes an open window through which body heat escapes into the environment. The solution is some kind of cover, but no really satisfactory face mask has ever been designed. ( onsequently every rider experiments endlessly. Some settle on the knit toque with an oval opening for the eyes. This works well to about 0 . although warm air has a way of creeping through the material and fogging your goggles. Below zero, breath moisture tends to condense and freeze, icing up almost any fabric mask. Another popular solution is the army surplus dust mask, which has a breather to release expired air some distance from the lace. I hese are not very comfortable, however, and they give one a grotesque appearance. Thus, until a good design becomes generally available, each rider must continue to work out his own face protection.

Hot your hands the best covering is determined by what kind of riding you do. Insulated mittens are by far the most effective protection. With gloves, the separate fingers disperse heat in the same manner as the fins on a cylinder. Yet for competition you may need the additional manipulation afforded by gloves. In either case, an outer shell of leather is best, with an insulating layer of knit wool or other material inside. Many riders simply combine two pairs of gloves, buying outers a size larger. Ski-tow mitts of sueded cowhide are an excellent choice, offering toughness and good gripping. These, too. can be made warmer with liner mittens. Hor extremely cold weather, arctic mittens are available in war surplus stores. The gauntlet style prevents forced drafts up the sleeves, and yet provides sufficient inlet for body ventilation.

Boots, like gloves and mittens, cannot ordinarily be used in ideal thicknesses of an inch or more. But insulated models are available, and should be purchased over the un lined variety. Inside the boot, you should wear a thin cotton or nylon sock next to the skin, then a heavy wool sock. A plastic mesh insole will provide additional insulation and ventilation as well as absorb foot moisture (sometimes as ice!). Hor a long distance ride at below-zero temperatures, a pair of surplus mukluks with padding can he worn over your boots for additional warmth. Before setting off. however, make sure you can adequately work the brake and shift levers.

Now you're padded from head to toe and feeling like the Abominable Snow Man. On the third of Hebruary you set out from Bismarck, North Dakota, headed for Fairbanks. Alaska. To your great dismay you detect a creeping chill along your spine. What possibilities remain? The answer is one of the many devices that can he fitted to your machine to reduce the deadly effect of the wind. Windshields have a nasty habit of curling the wind over your head and down your back, but it comes in at reduced force and at a less damaging angle. Leather shields can be added to your handlebars, or a handlebar fairing. Naturally the most protection is provided by a full touring fairing. This serves the double advantage of diminishing the wind and trapping a little engine warmth where it does the most good. The net effect on your heat loss can be equivalent to a 30 degree increase in temperature. Hot people who ride often in the cold, there is some justification for these compromises to “pure” motorcycling.

Once you've begun a long ride, there are a few techniques that help keep you going. T he first and most important is never to let yourself get really cold. Before a deep chill sets in. do something. Stop for coffee, hot soup or a warm meal. If this isn’t possible, remember that you have enormous amounts of latent heat stored away in your body. To release it. get off and do some exercises, or push your machine through a hundred yards of deep snow. Don't continue to the point of sweating, just get your system turning over at a higher rate. While riding, you can exercise your hands and wriggle your toes to keep up circulation. Another thing to remember is that fatigue, like anxiety, greatly reduces your ability to cope with the cold: get enough sleep and eat regularly. These precautions and warm clothing should enable you to ride indefinitely. Instead of impatiently sitting it out. the well prepared motorcyclist can fully enjoy riding throughout the winter season. •