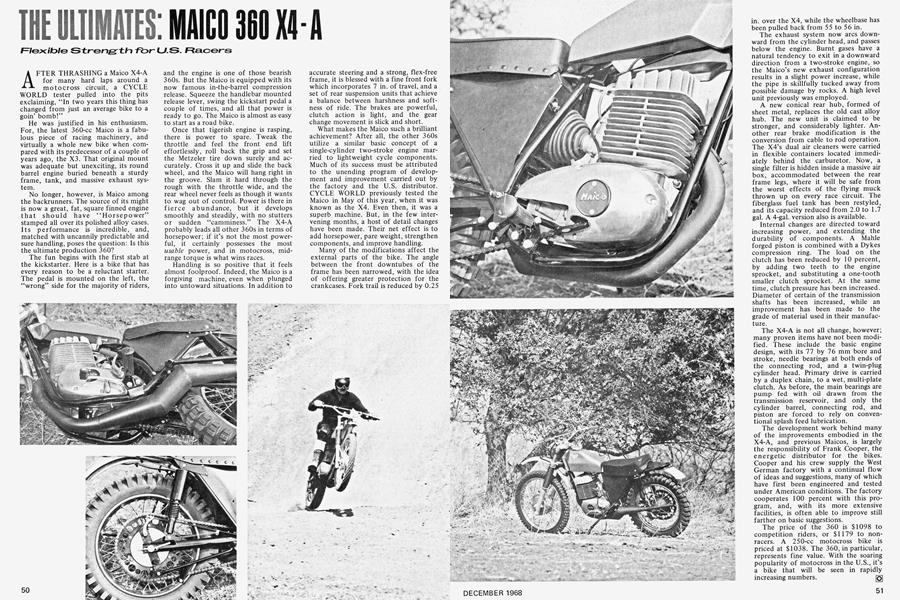

THE ULTIMATES:MAICO 360 X4-4

Flexible Strength for U.S.Racers

AFTER THRASHING a Maico X4-A for many hard laps around a motocross circuit, a CYCLE WORLD tester pulled into the pits exclaiming, “In two years this thing has changed from just an average bike to a goin’ bomb!”

He was justified in his enthusiasm. For, the latest 360-cc Maico is a fabulous piece of racing machinery, and virtually a whole new bike when compared with its predecessor of a couple of years ago, the X3. That original mount was adequate but unexciting, its round barrel engine buried beneath a sturdy frame, tank, and massive exhaust system.

No longer, however, is Maico among the backrunners. The source of its might is now a great, fat, square finned engine that should have “Horsepower” stamped all over its polished alloy cases. Its performance is incredible, and, matched with uncannily predictable and sure handling, poses the question: Is this the ultimate production 360?

The fun begins with the first stab at the kickstarter. Here is a bike that has every reason to be a reluctant starter. The pedal is mounted on the left, the “wrong” side for the majority of riders, and the engine is one of those bearish 360s. But the Maico is equipped with its now famous in-the-barrel compression release. Squeeze the handlebar mounted release lever, swing the kickstart pedal a couple of times, and all that power is ready to go. The Maico is almost as easy to start as a road bike.

Once that tigerish engine is rasping, there is power to spare. Tweak the throttle and feel the front end lift effortlessly, roll back the grip and set the Metzeler tire down surely and accurately. Cross it up and slide the back wheel, and the Maico will hang right in the groove. Slam it hard through the rough with the throttle wide, and the rear wheel never feels as though it wants to wag out of control. Power is there in fierce abundance, but it develops smoothly and steadily, with no stutters or sudden “camminess.” The X4-A probably leads all other 360s in terms of horsepower; if it’s not the most powerful, it certainly possesses the most usable power, and in motocross, midrange torque is what wins races.

Handling is so positive that it feels almost foolproof. Indeed, the Maico is a forgiving machine, even when plunged into untoward situations. In addition to accurate steering and a strong, flex-free frame, it is blessed with a fine front fork which incorporates 7 in. of travel, and a set of rear suspension units that achieve a balance between harshness and softness of ride. The brakes are powerful, clutch action is light, and the gear change movement is slick and short.

What makes the Maico such a brilliant achievement? After all, the other 360s utilize a similar basic concept of a single-cylinder two-stroke engine married to lightweight cycle components. Much of its success must be attributed to the unending program of development and improvement carried out by the factory and the U.S. distributor. CYCLE WORLD previously tested the Maico in May of this year, when it was known as the X4. Even then, it was a superb machine. But, in the few intervening months, a host of detail changes have been made. Their net effect is to add horsepower, pare weight, strengthen components, and improve handling.

Many of the modifications affect the external parts of the bike. The angle between the front downtubes of the frame has been narrowed, with the idea of offering greater protection for the crankcases. Fork trail is reduced by 0.25 in. over the X4, while the wheelbase has been pulled back from 55 to 56 in.

The exhaust system now arcs downward from the cylinder head, and passes below the engine. Burnt gases have a natural tendency to exit in a downward direction from a two-stroke engine, so the Maico’s new exhaust configuration results in a slight power increase, while the pipe is skillfully tucked away from possible damage by rocks. A high level unit previously was employed.

A new conical rear hub, formed of sheet metal, replaces the old cast alloy hub. The new unit is claimed to be stronger, and considerably lighter. Another rear brake modification is the conversion from cable to rod operation. The X4’s dual air cleaners were carried in flexible containers located immediately behind the carburetor. Now, a single filter is hidden inside a massive air box, accommodated between the rear frame legs, where it will be safe from the worst effects of the flying muck thrown up on every race circuit. The fiberglass fuel tank has been restyled, and its capacity reduced from 2.0 to 1.7 gal. A 4-gal. version also is available.

Internal changes are directed toward increasing power, and extending the durability of components. A Mahle forged piston is combined with a Dykes compression ring. The load on the clutch has been reduced by 10 percent, by adding two teeth to the engine sprocket, and substituting a one-tooth smaller clutch sprocket. At the same time, clutch pressure has been increased. Diameter of certain of the transmission shafts has been increased, while an improvement has been made to the grade of material used in their manufacture.

The X4-A is not all change, however; many proven items have not been modified. These include the basic engine design, with its 77 by 76 mm bore and stroke, needle bearings at both ends of the connecting rod, and a twin-plug cylinder head. Primary drive is carried by a duplex chain, to a wet, multi-plate clutch. As before, the main bearings are pump fed with oil drawn from the transmission reservoir, and only the cylinder barrel, connecting rod, and piston are forced to rely on conventional splash feed lubrication.

The development work behind many of the improvements embodied in the X4-A, and previous Maicos, is largely the responsibility of Frank Cooper, the energetic distributor for the bikes. Cooper and his crew supply the West German factory with a continual flow of ideas and suggestions, many of which have first been engineered and tested under American conditions. The factory cooperates 100 percent with this program, and, with its more extensive facilities, is often able to improve still farther on basic suggestions.

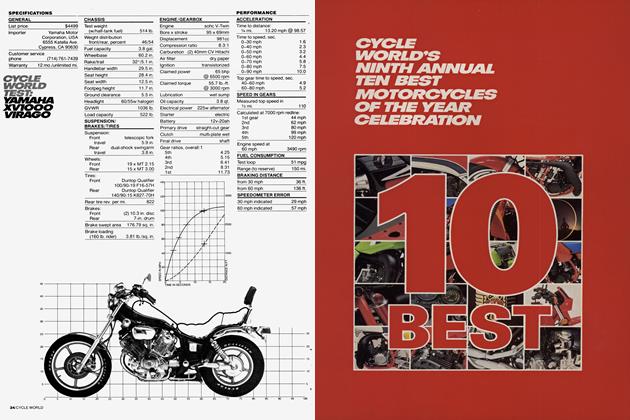

The price of the 360 is $1098 to competition riders, or $1179 to nonracers. A 250-cc motocross bike is priced at $1038. The 360, in particular, represents fine value. With the soaring popularity of motocross in the U.S., it’s a bike that will be seen in rapidly increasing numbers. [Q]