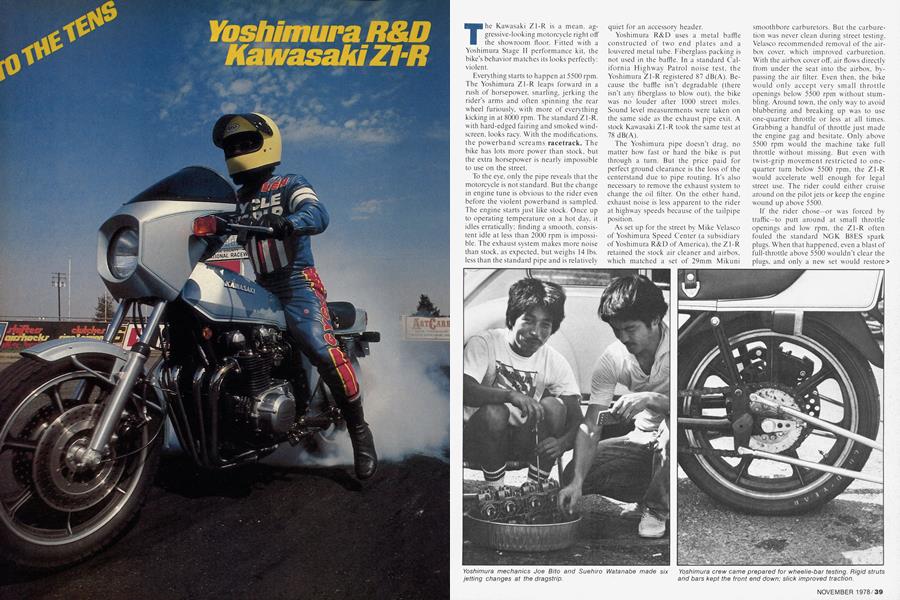

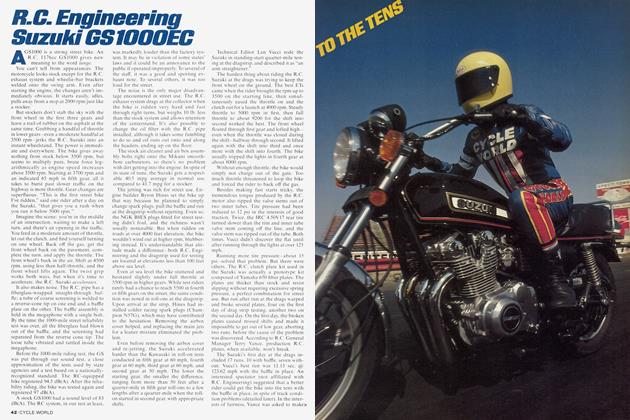

Yoshimura R&D Kawasaki Z1-R

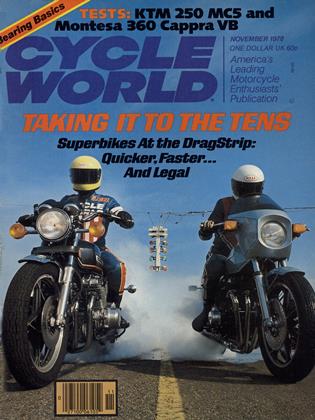

TO THE TENS

The Kawasaki Z1-R is a mean, aggressive-looking motorcycle right off the showroom floor. Fitted with a Yoshimura Stage II performance kit, the bike's behavior matches its looks perfectly: violent.

Everything starts to happen at 5500 rpm. The Yoshimura Z1-R leaps forward in a rush of horsepower, snarling, jerking the rider's arms and often spinning the rear wheel furiously, with more of everything kicking in at 8000 rpm. The standard Z1-R. with hard-edged fairing and smoked windscreen. looks racy. With the modifications, the powerband screams racetrack. The bike has lots more power than stock, but the extra horsepower is nearly impossible to use on the street.

To the eye, only the pipe reveals that the motorcycle is not standard. But the change in engine tune is obvious to the rider even before the violent powerband is sampled. The engine starts just like stock. Once up to operating temperature on a hot day, it idles erratically; finding a smooth, consistent idle at less than 2000 rpm is impossible. The exhaust system makes more noise than stock, as expected, but weighs 14 lbs. less than the standard pipe and is relatively quiet for an accessory header.

Yoshimura R&D uses a metal baffle constructed of two end plates and a louvered metal tube. Fiberglass packing is not used in the baffle. In a standard California Highway Patrol noise test, the Yoshimura Zl-R registered 87 dB(A). Because the baffle isn't degradable (there isn't any fiberglass to blow out), the bike was no louder after 1000 street miles. Sound level measurements were taken on the same side as the exhaust pipe exit. A stock Kawasaki Zl-R took the same test at 78 dB(A).

The Yoshimura pipe doesn't drag, no matter how fast or hard the bike is put through a turn. But the price paid for perfect ground clearance is the loss of the centerstand due to pipe routing. It's also necessary to remove the exhaust system to change the oil filter. On the other hand, exhaust noise is less apparent to the rider at highway speeds because of the tailpipe position.

As set up for the street by Mike Velasco of Yoshimura Speed Center (a subsidiary of Yoshimura R&D of America), the Zl-R retained the stock air cleaner and airbox, which matched a set of 29mm Mikuni smoothbore carburetors. But the carburetion was never clean during street testing. Velasco recommended removal of the airbox cover, which improved carburetion. With the airbox cover off, air flows directly from under the seat into the airbox, bypassing the air filter. Even then, the bike would only accept very small throttle openings below 5500 rpm without stumbling. Around town, the only way to avoid blubbering and breaking up was to use one-quarter throttle or less at all times. Grabbing a handful of throttle just made the engine gag and hesitate. Only above 5500 rpm would the machine take full throttle without missing. But even with twist-grip movement restricted to onequarter turn below 5500 rpm, the Zl-R would accelerate well enough for legal street use. The rider could either cruise around on the pilot jets or keep the engine wound up above 5500.

If the rider chose—or was forced by traffic—to putt around at small throttle openings and low rpm, the Zl-R often fouled the standard NGK B8ES spark plugs. When that happened, even a blast of full-throttle above 5500 wouldn't clear the plugs, and only a new set would restore > performance. The bike's gas mileage dropped drastically to an average of 38.2 mpg. compared to 45.5 for a stock Zl-R.

The story was different above 5500. At that rpm or above, the engine took any throttle setting, whether delivered smoothly or in great chunks. Roll on the throttle. The Yoshimura Zl-R moves out briskly. Grab a handful. The Yoshimura machine leaps forward. The answer, then, to making fast freeway passes lies in downshifting several times, grabbing a big bunch of throttle and hanging on for dear life. On uncrowded, twisting roads suitable for high-speed, high-rpm (above 5500) running in lower gears, the bike performed perfectly.

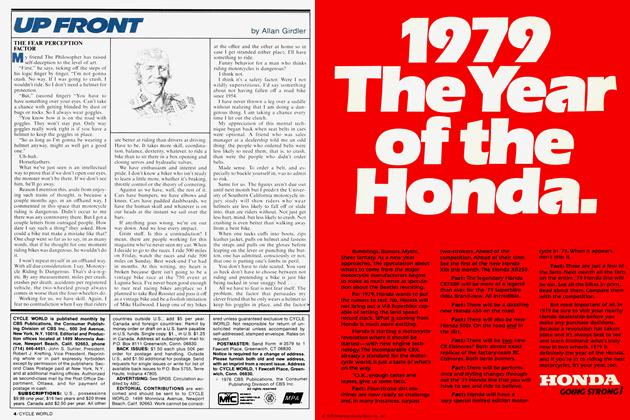

It was the same story in roll-on tests at the dragstrip. Chief Yoshimura R&D of America racing mechanic Suehiro Watanabe and his assistant, Joe Bito, accompanied Velasco to the track and immediately installed ND W27EPT racing spark plugs. In the first few roll-ons, the Zl-R sputtered and spit while the Suzuki pulled away. Watanabe and Bito replaced the carburetors with another set of Mikuni smoothbores, changed the pilot jets .from size 25 to size 40, went from 132.5 main jets to 125 main jets, and removed the airbox and air cleaner.

The Kawasaki immediately ran better, still spitting a little below 5500 and still behind the Suzuki. In the last roll-on, starting in second gear from 50 mph, the Yoshimura Zl-R ran close to the Suzuki.

Standing-start quarter-mile runs followed. Turning low ETs with the Kawasaki was a matter of matching engine powerband to available traction. The Zl-R comes with a 4.00H18 rear tire which isn't made for dragstrip use. The tire would light up and spin for hundreds of feet if the

rider came out of the gate above 8000 rpm, where the engine made its most power. Lowering tire pressure to about 15 psi helped.

The best runs started at 8500 rpm, the rider easing the clutch out very quickly— but not letting it snap into engagement— and applying full throttle about 20 feet out of the gate. After powershifts at 9500 rpm into second and third, the bike tripped the lights at about 10,200 rpm in third.

Before the first runs with the baffle in, Watanabe and Bito again changed the Zl-R's main jets, from 125 to 130. Technical editor Len Vucci made three passes, let the bike cool off. and made three more runs, the best being 11.54 sec. @ 116.42 mph.

While the Kawasaki cooled. Vucci rode the Suzuki, which complicated things—the two bikes required very different riding techniques. An interested spectator in the Yoshimura pits suggested that the Zl-R could be made to turn quicker times with another rider. Yoshimura's Velasco was invited to ride. He made two passes with the baffle in. one at 11.47 (a) 116.58. the other at 11.54(a) 115.97.

We were most interested in testing with the baffle out, so Watanabe and Bito again rejetted the carburetors, going from 130 main jets to 120 main jets, and the baffle was pulled.

Velasco made three passes, the fastest 11.08 (a) 120.00 mph. In two runs, Vucci's best time was 11.19 (a) 122.28. and the clutch was starting to slip.

It was time to prepare for the next morning when cooler air and better track conditions might lower ETs. The Yoshimura crew installed a new clutch, changed the oil and filter, replaced spark plugs, changed from the stock 15-tooth countershaft sprocket to a 14-tooth sprocket

(the size used on KZ 1000s) and fitted a new stock rear tire. During the evening, meanwhile, grudge racers burned the oil off the track and coated the starting area with a fresh layer of rubber.

Next morning we picked up where we left off, testing without baffle. Velasco made five runs in succession, the best 11.08 @ 124.01. Vucci followed with three runs, the best 11.15 (a) 123.28.

Vucci burned the rear tire'flat. positioning the front wheel against a steel crash barrier, revving up the engine and dumping the clutch. The tire spun in a cloud of smoke as rubber wore away, removing all the tread and finally producing a flat, semislick drag-racing tire. He followed with three runs, the best 11.15 (a) 123.28. Then Velasco made a pass at 11.18 @ 123.62.

Watanabe and Bito installed velocity stacks on the carburetors and rejetted from 125 main jets to 120 main jets. Then, in six consecutive runs, Vucci worked the Yoshimura Zl-R down into the 10s.

Progress was slow and nerve-wracking. The first pass. 11.03@ 124.13. The second, 11.06 (a) 123.45. Then, in quick order, 11.26(a) 121.29. 11.02 @ 122.61, 11.01 @ 123.28. Finally, an absolutely perfect pass—everyone knew it was the run as soon as Vucci left the start—yielding 10.80 (a) 124.13.

Watanabe apologized for it having taken so long. "We do not have much drag racing experience," said Watanabe, the man responsible for building Wes Cooley's Superbike Production road racing missiles.

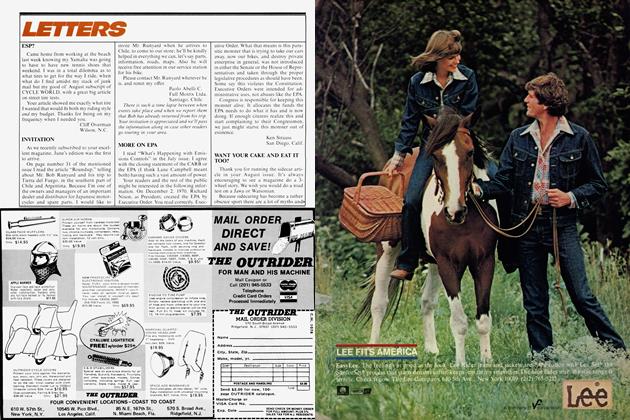

The Yoshimura crew took the last part of the dragstrip testing—without baffle, but with wheelie bars and slick—seriously. They came equipped with a set of American Turbo-Pak wheelie bars and struts and a spare wheel fitted with a Goodyear 1381A road racing tire. They lowered the front end by dropping the triple clamps down on the fork tubes, bolted up the bars and struts, and re-jetted the carburetors for the sixth time, going from 120 main jets to 117.5 main jets. Their efforts were rewarded with a fast time of 10.62 @ 123.62, set by Vucci in four runs. Velasco made one run, 10.79 @ 122.49.

After 33 trips down the strip the Zl-R was still running as well as ever. Top speed tests followed immediately. Clocked by our calibrated radar gun, the Kawasaki reached 141 mph after a half-mile run.

After the bike had been returned to its owner, Fujio Yoshimura, Vice President of Yoshimura R&D, told us that different pilot jets in the smoothbore Mikunis would have cured the carburetion problems we had encountered on the street. However, we did not have time to re-test the Kawasaki before going to press.

We might have gotten better performance by using a KZ 1000 or an LTD as the base machine. The KZ1000 is lighter than the Zl-R, while the LTD comes standard with a 5.10H16 rear tire, which would have improved traction for testing without wheelie bars.

The Yoshimura Stage II 1105cc kit installed in the test Zl-R included 73mm pistons (with rings, pins, clips and head gasket), oversize intake and exhaust valves. Bonneville camshafts, heavy-duty valve springs and cylinder head porting and polishing (including combustion chamber modifications, valve recontouring and valve polishing). According to Velasco, the price includes labor for installation. The Mikuni 29mm smoothbore carburetors were extra, as was the exhaust system and Martek 440 pointless electronic ignition system. Velasco told us that carburetor, exhaust pipe and ignition installation charges were included if a customer bought everything at the same time with the Stage II kit.

Total price came to $1657.75.

That's not exactly cheap.

But then, violence never is.

STOCK Z1-R

Yoshimura R&D of America 5517 Cleon Ave. North Hollywood, CA 91601 (213) 985-2331

YOSHIMURA Z1-R

Yoshimura Speed Center 1958 Placentia Ave. Costa Mesa, CA 92626 (714) 642-7094

$1079.00

View Full Issue

View Full Issue