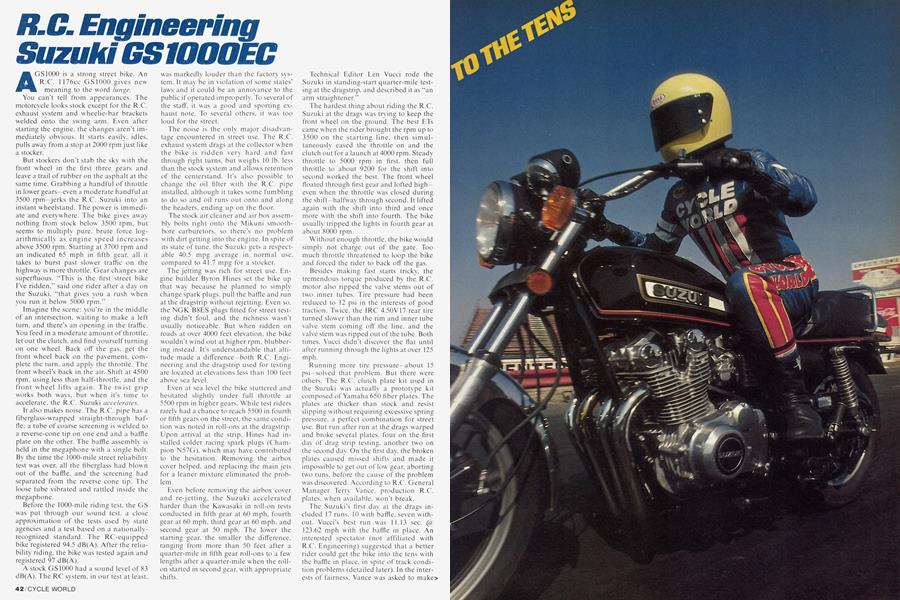

R.C. Engineering Suzuki GS1000EC

A GS1000 is a strong street bike. An R.C. 176cc GS1000 gives new meaning to the word lunge.

You can't tell from appearances. The motorcycle looks stock except for the R.C. exhaust system and wheelie-bar brackets welded onto the swing arm. Even after starting the engine, the changes aren't immediately obvious. It starts easily, idles, pulls away from a stop at 2000 rpm just like a stocker.

But stockers don't stab the sky with the front wheel in the first three gears and leave a trail of rubber on the asphalt at the same time. Grabbing a handful of throttle in lower gears—even a moderate handful at 3500 rpm—jerks the R.C. Suzuki into an instant wheelstand. The power is immediate and everywhere. The bike gives away nothing from stock below' 3500 rpm. but seems to multiply pure, brute force logarithmically as engine speed increases above 3500 rpm. Starting at 3700 rpm and an indicated 65 mph in fifth gear, all it takes to burst past slower traffic on the highway is more throttle. Gear changes are superfluous. "This is the first street bike I've ridden," said one rider after a day on the Suzuki, "that gives you a rush when you run it below 5000 rpm."

Imagine the scene: you're in the middle of an intersection, waiting to make a left turn, and there's an opening in the traffic. You feed in a moderate amount of throttle, let out the clutch, and find yourself turning on one wheel. Back off the gas, get the front wheel back on the pavement, complete the turn, and apply the throttle. The front wheel's back in the air. Shift at 4500 rpm, using less than half-throttle, and the front wheel lifts again. The twist grip works both ways, but when it's time to accelerate, the R.C. Suzuki accelerates.

It also makes noise. The R.C. pipe has a fiberglass-wrapped straight-through baffle; a tube of coarse screening is w'elded to a reverse-cone tip on one end and a baffle plate on the other. The baffle assembly is held in the megaphone with a single bolt. By the time the 1000-mile street reliability test was over, all the fiberglass had blown out of the baffle, and the screening had separated from the reverse cone tip. The loose tube vibrated and rattled inside the megaphone.

Before the 1000-mile riding test, the GS was put through our sound test, a close approximation of the tests used by state agencies and a test based on a nationallyrecognized standard. The RC-equipped bike registered 94.5 dB(A). After the reliability riding, the bike w'as tested again and registered 97 dB(A).

A stock GS 1000 had a sound level of 83 dB(A). The RC system, in our test at least. was markedly louder than the factory system. It may be in violation of some states' laws and it could be an annoyance to the public if operated improperly. To several of the staff, it was a good and sporting exhaust note. To several others, it was too loud for the street.

The noise is the only major disadvantage encountered in street use. The R.C. exhaust system drags at the collector w hen the bike is ridden very hard and fast through right turns, but weighs 10 lb. less than the stock system and allows retention of the centerstand. It's also possible to change the oil filter with the R.C. pipe installed, although it takes some fumbling to do so and oil runs out onto and along the headers, ending up on the floor.

The stock air cleaner and air box assembly bolts right onto the Mikuni smoothbore carburetors, so there's no problem with dirt getting into the engine. In spite of its state of tune, the Suzuki gets a respectable 40.5 mpg average in normal use, compared to 41.7 mpg for a stocker.

The jetting was rich for street use. Engine builder Byron Hines set the bike up that w'ay because he planned to simply change spark plugs, pull the baffle and run at the dragstrip without rejetting. Even so, the NGK B8ES plugs fitted for street testing didn't foul, and the richness wasn't usually noticeable. But when ridden on roads at over 4000 feet elevation, the bike wouldn't wind out at higher rpm. blubbering instead. It's understandable that altitude made a difference—both R.C. Engineering and the dragstrip used for testing are located at elevations less than 100 feet above sea level.

Even at sea level the bike stuttered and hesitated slightly under full throttle at 5500 rpm in higher gears. While test riders rarely had a chance to reach 5500 in fourth or fifth gears on the street, the same condition w'as noted in roll-ons at the dragstrip. Upon arrival at the strip, Hines had installed colder racing spark plugs (Champion N57G). which may have contributed to the hesitation. Removing the airbox cover helped, and replacing the main jets for a leaner mixture eliminated the problem.

Even before removing the airbox cover and re-jetting, the Suzuki accelerated harder than the Kaw'asaki in roll-on tests conducted in fifth gear at 60 mph, fourth gear at 60 mph, third gear at 60 mph, and second gear at 50 mph. The low'er the starting gear, the smaller the difference, ranging from more than 50 feet after a quarter-mile in fifth gear roll-ons to a few lengths after a quarter-mile when the rollon started in second gear, with appropriate shifts. Technical Editor Len Vucci rode the Suzuki in standing-start quarter-mile testing at the dragstrip, and described it as "an arm straightener."

The hardest thing about riding the R.C. Suzuki at the drags was trying to keep the front wheel on the ground. The best ETs came when the rider brought the rpm up to 3500 on the starting line, then simultaneously eased the throttle on and the clutch out for a launch at 4000 rpm. Steady throttle to 5000 rpm in first, then full throttle to about 9200 for the shift into second worked the best. The front wheel floated through first gear and lofted higheven when the throttle was closed during the shift—halfway through second. It lifted again w'ith the shift into third and once more with the shift into fourth. The bike usually tripped the lights in fourth gear at about 8000 rpm.

Without enough throttle, the bike would simply not charge out of the gate. Too much throttle threatened to loop the bike and forced the rider to back off the gas.

Besides making fast starts tricky, the tremendous torque produced by the R.C. motor also ripped the valve stems out of tw'o inner tubes. Tire pressure had been reduced to 12 psi in the interests of good traction. Twice, the IRC 4.50V 17 rear tire turned slower than the rim and inner tube valve stem coming off the line, and the valve stem was ripped out of the tube. Both times, Vucci didn't discover the flat until after running through the lights at over 125 mph.

Running more tire pressure—about 15 psi—solved that problem. But there w'ere others. The R.C. clutch plate kit used in the Suzuki was actually a prototype kit composed of Yamaha 650 fiber plates. The plates are thicker than stock and resist slipping without requiring excessive spring pressure, a perfect combination for street use. But run after run at the drags warped and broke several plates, four on the first day of drag strip testing, another two on the second day. On the first day, the broken plates caused missed shifts and made it impossible to get out of low gear, aborting two runs, before the cause of the problem was discovered. According to R.C. General Manager Terry Vance, production R.C. plates, when available, won't break.

The Suzuki's first day at the drags included 17 runs. 10 with baffle, seven without. Vucci's best run was 11.13 sec. @ 123.62 mph with the baffle in place. An interested spectator (not affiliated with R.C. Engineering) suggested that a better rider could get the bike into the tens with the baffle in place, in spite of track condition problems (detailed later). In the interests of fairness. Vance was asked to make>

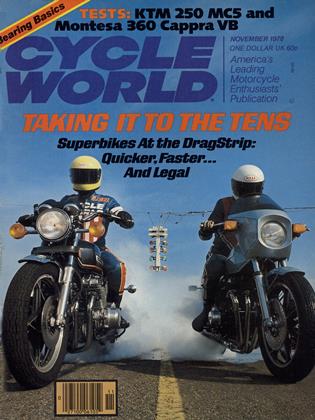

TO THE TENS

several runs. Of the 10 runs made with the baffle in place, Vance made four and Vucci made six. Vance's best run was 11.36 @ 122.78. But while the comparative times helped settle a minor controversy, it is impossible to say what effect the broken clutch plates played in the drama, since it isn't known exactly when the plates broke or how many were broken at any given time prior to discovery.

As already noted, Hines had re-jetted the Suzuki for best performance with the exhaust baffle before the roll-ons had been completed. Between runs made with the baffle and runs made without the baffle, he returned the jetting to the way it had been in the first place—up from 110 main jets to 115 main jets. He also removed the air cleaner and disconnected the crankcase breather hose (which normally runs between the cam cover and the airbox), so oil blown out at high rpm wouldn't affect carburetion.

The best run without the baffle again belonged to Vucci: 11:07 @ 125.17 on the third of six runs. Vance made one run, 11.10 @ 126.05 and handed the bike back to Vucci.

Halfway through the runs made without the baffle, the exhaust pipe's rear mounting bracket broke. According to Vance, running without a baffle sets up ^ resonance which can fatigue the bracket; in such cases, pipes are replaced by R.C. under a limited warranty.

By this time, it was obvious that the Suzuki wasn't going to get into the 10s on that day. Roll-on tests and the tire and clutch problems had used up the morning, when the air is cool and dense and ETs are lower. The dragstrip itself was slippery with oil—a car using the track the same day blew up a few hundred feet out of the lights in one lane; oil from the Yamaha streaked the other lane. A headwind came up in the afternoon, and a mass of cars and bikes waiting at the track entrance reminded us that we had to finish by 5 p.m. to make way for the regularly-scheduled grudge night events. So we packed up and left.

Track workers burned off the oil before the grudge races, during which competing vehicles laid plenty of fresh, high-traction rubber on both lanes of the strip.

As hoped, everything came together on the second day of testing. We were most interested in the times obtained without the baffle but with stock tire and suspension, so that's the combination we started out with. Vance made the first three runs, the best 10.81 @ 129.31. Vucci followed with three runs, the best 10.93 @ 127.47. Hines replaced two broken clutch plates and Vucci made four more runs, the first of the set 10.73 @ 128.57, backed up by (in order) 10.77 @ 127.47, 10.75 @ 129.12 and 10.76 @ 128.93.

Because Vance and Hines were also most interested in times turned with the stock tire and suspension, they didn't take the wheelie-bar and slick test very seriously. They had brought bar and spare rear wheel mounted with a Goodyear 1381 road racing slick, but hadn't brought struts. The Suzuki looked like a kangaroo leaving

the gate. The wheelie bars helped, but the torque compressed the shock absorbers and the front wheel hopped all the way down the strip as the shock springs fought back. Finally, Hines jury-rigged a tiedown strap from one side of the swing arm, over the rear fender (but under the seat) and onto the other side of the swing arm. With three people pushing down on the Suzuki's rear end and Hines cinching up the tie-down strap, the shock springs were compressed into more-or-less-rigid suspension.

Vance's best of four runs yielded 10.53 @ 127.19. Vucci followed with five runs, the fastest 10.43 @ 128.02, backed up by 10.43 @ 126.22. That run was the 36th and the last for the Suzuki. Just as Vucci went through the ET lights, the engine note changed. A check revealed no compression in one cylinder.

The next day the bike was returned to R.C. Engineering for a teardown. One valve spring had broken. Although the valve had hit the piston slightly, it wasn't bent. All the valve springs were replaced, the valve resurfaced and the bike reassembled. According to Vance, it was the first RC valve spring he has seen break. He called it a fluke and said that a similar failure in an engine built by R.C. for a customer would have been repaired without charge.

Once fixed, the bike returned to the dragstrip for top speed testing. Without the baffle, the Suzuki registered 148 mph on the Cycle World calibrated radar gun after a half-mile run.

After all that—street testing, dragstrip runs, top speed tests—the stock Suzuki drive chain hadn't stretched enough to require replacement. However, the GS1000 emblems on the side covers had fallen off, and before the cover photo session was over, the rear tire was down to the cords. (A look at the cover will show why).

If we had used a standard GS1000C model rather than the deluxe GS1000EC with cast wheels and dual-disc front brake, we might have gotten better performance figures—the C model is lighter than the EC version. But the C model also comes with a narrower, 18-inch rear tire. Anyway, the R.C. kit made more than enough power.

The modifications that unleashed that power were extensive and costly. (See chart for specifications and prices.) They started with the 1176cc piston kit, complete with pistons, rings, wrist pins, teflon-button wrist-pin retainers and head gasket. The 6mm increase over stock bore size exceeded the capacity of the standard liners. Oversize liners were pressed into the cylinder block and the crankcases were bored to accept the larger liners. The pistons raise compression significantly, so grooves were milled around each cylinder for a compression-retaining copper O-ring. The piston kit came with an aluminum head gasket; we used an optional copper head gasket for severe' use.

Because the full 1176cc engine makes so much more horsepower than stock, the pressed-together standard crankshaft was welded together to prevent any movement and misalignment of crank parts under hard use.

According to Hines, the cylinder head is the key to power. Our test bike's head got the full R.C. treatment: porting, polishing, and relieving around the valve seats. Valves, cam follower buckets and shims remained stock; heavy-duty valve springs were used. A set of R.C. 400 hardweld cams were installed, along with a set of Mikuni smoothbore carburetors, an R.C. exhaust system, and an R.C. inductive, pointless electronic ignition system. Hines claims that the R.C. ignition is good for a tenth of a second in the quarter because point bounce at high rpm is eliminated and coil saturation time is increased. An R.C. clutch kit completed the package.

The total price came to $1964.85, with parts ringing up $1083.85 and labor accounting for another $881.00.

It was expensive.

It was also very, very fast.

STOCK GS 1000EC

RC GS1 1000EC

$1964.85

R.C. Engineering 16216 S. Main St. Gardena, CA 90248 (213) 327-6858

View Full Issue

View Full Issue