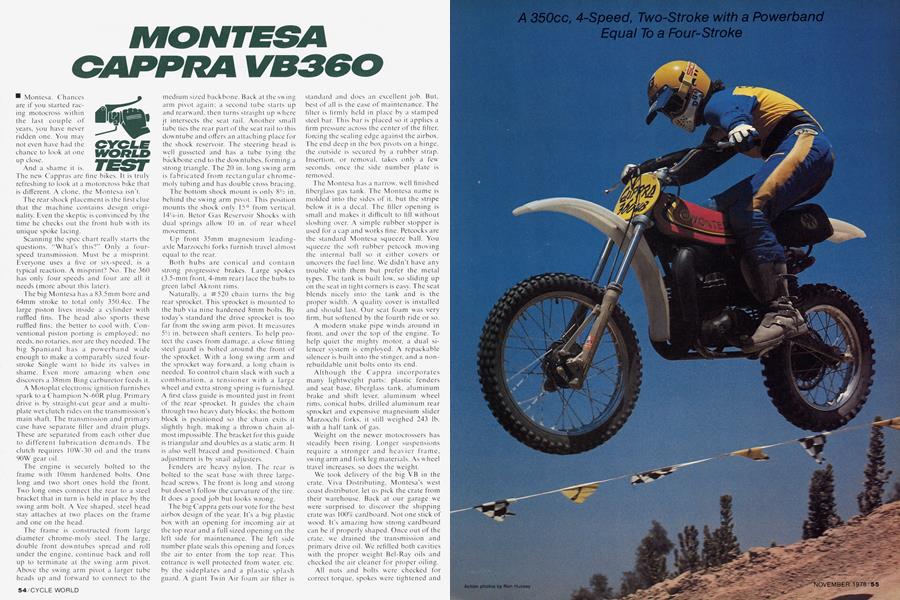

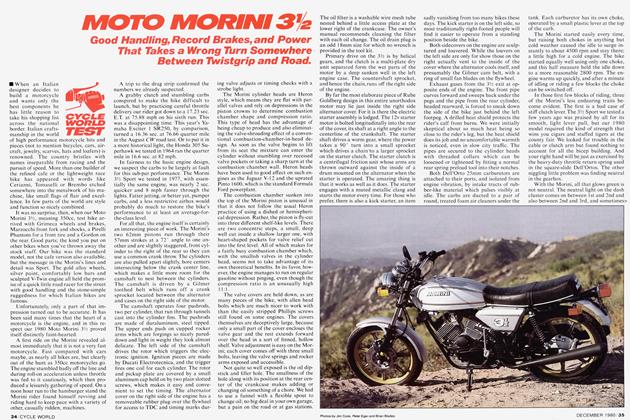

MONTESA CAPPRA VB360

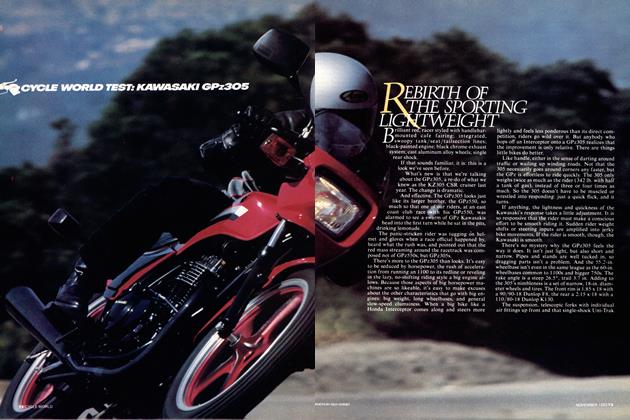

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Montesa. Chances are if you started racing motocross within the last couple of years, you have never ridden one. You may not even have had the chance to look at one up close.

And a shame it is.

The new Cappras are fine hikes. It is truly refreshing to look at a motorcross bike that is different. A clone, the Montesa isn't.

The rear shock placement is the first clue that the machine contains design originality. Even the skeptic is convinced by the time he checks out the front hub with its unique spoke lacing.

Scanning the spec chart really starts the questions. "What's this?" Only a fourspeed transmission. Must be a misprint. Everyone uses a five or six-speed, is a typical reaction. A misprint? No. The 360 has only four speeds and four are all it needs (more about this later).

The big Montesa has a 83.5mm bore and 64mm stroke to total only 350.4cc. The large piston lives inside a cylinder with ruffled fins. The head also sports these ruffled fins; the better to cool with. Conventional piston porting is employed; no reeds, no rotaries, nor are they needed. The big Spaniard has a powerband wide enough to make a comparably sized fourstroke Single want to hide its valves in shame. Even more amazing when one discovers a 38mm Bing carburetor feeds it.

A Motoplat electronic ignition furnishes spark to a Champion N-60R plug. Primary drive is by straight-cut gear and a multiplate wet clutch rides on the transmission's main shaft. The transmission and primary case have separate filler and drain plugs. These are separated from each other due to different lubrication demands. The clutch requires 10W-30 oil and the trans 90W gear oil.

The engine is securely bolted to the frame with 10mm hardened bolts. One long and two short ones hold the front. Two long ones connect the rear to a steel bracket that in turn is held in place by the swing arm bolt. A Vee shaped, steel head stay attaches at two places on the frame and one on the head.

The frame is constructed from large diameter chrome-moly steel. The large, double front downtubes spread and roll under the engine, continue back and roll up to terminate at the swing arm pivot. Above the swing arm pivot a larger tube heads up and forward to connect to the

medium sized backbone. Back at the sw ing arm pivot again; a second tube starts up and rearward, then turns straight up where it intersects the seat rail. Another small

tube ties the rear part of the seat rail to this downtube and offers an attaching place for the shock reservoir. The steering head is well gusseted and has a tube tying the backbone end to the dow ntubes, forming a strong triangle. The 20 in. long swing arm is fabricated from rectangular chromemoly tubing and has double cross bracing.

The bottom shock mount is only 8'A in. behind the swing arm pivot. This position mounts the shock only 15° from vertical. 14'A-in. Betor Gas Reservoir Shocks with dual springs allow 10 in. of rear wheel movement.

Up front 35mm magnesium leadingaxle Marzocchi forks furnish travel almost equal to the rear.

Both hubs are conical and contain strong progressive brakes. Large spokes (3.5-mm front, 4-mm rear) lace the hubs to green label Akront rims.

Naturally, a #520 chain turns the big rear sprocket. This sprocket is mounted to the hub via nine hardened 8mm bolts. By today's standard the drive sprocket is too far from the swing arm pivot. It measures 5‘A in. between shaft centers. To help protect the cases from damage, a close fitting steel guard is bolted around the front of the sprocket. With a long sw ing arm and the sprocket way forward, a long chain is needed. To control chain slack with such a combination, a tensioner with a large wheel and extra strong spring is furnished. A first class guide is mounted just in front of the rear sprocket. It guides the chain through two heavy duty blocks; the bottom block is positioned so the chain exits it slightly high, making a thrown chain almost impossible. The bracket for this guide is triangular and doubles as a static arm. It is also well braced and positioned. Chain adjustment is by snail adjusters.

Fenders are heavy nylon. The rear is bolted to the seat base with three largehead screws. The front is long and strong but doesn't follow the curvature of the tire. It does a good job but looks w rong.

The big Cappra gets our vote for the best airbox design of the year. It's a big plasticbox with an opening for incoming air at the top rear and a full sized opening on the left side for maintenance. The left side number plate seals this opening and forces the air to enter from the top rear. This entrance is well protected from water, etc. by the sideplates and a plastic splash guard. A giant Twin Air foam air filter is

standard and does an excellent job. But, best of all is the ease of maintenance. The filter is firmly held in place by a stamped steel bar. This bar is placed so it applies a firm pressure across the center of the filter, forcing the sealing edge against the airbox. The end deep in the box pivots on a hinge, the outside is secured by a rubber strap. Insertion, or removal, takes only a few seconds, once the side number plate is removed.

The Montesa has a narrow, well finished fiberglass gas tank. The Montesa name is molded into the sides of it. but the stripe below it is a decal. The filler opening is small and makes it difficult to fill without sloshing over. A simple rubber stopper is used for a cap and works fine. Petcocks are the standard Montesa squeeze ball. You squeeze the soft rubber petcock moving the internal ball so it either covers or uncovers the fuel line. We didn't have any trouble with them but prefer the metal types. The tank is built low, so sliding up on the seat in tight corners is easy. The seat blends nicely into the tank and is the proper width. A quality cover is installed and should last. Our seat foam was very firm, but softened by the fourth ride or so.

A modern snake pipe winds around in front, and over the top of the engine. To help quiet the mighty motor, a dual silencer system is employed. A repackable silencer is built into the stinger, and a nonrebuildable unit bolts onto its end.

Although the Cappra incorporates many lightweight parts: plastic fenders and seat base, fiberglass tank, aluminum brake and shift lever, aluminum wheel rims, conical hubs, drilled aluminum rear sprocket and expensive magnesium slider Marzocchi forks, it still weighed 243 lb. with a half tank of gas.

Weight on the newer motocrossers has steadily been rising. Longer suspensions require a stronger and heavier frame, sw ing arm and fork leg materials. As w heel travel increases, so does the weight.

We took delivery of the big VB in the crate. Viva Distributing, Montesa's west coast distributor, let us pick the crate from their warehouse. Back at our garage we were surprised to discover the shipping crate was 100% cardboard. Not one stick of wood. It's amazing how strong cardboard can be if properly shaped. Once out of the crate, we drained the transmission and primary drive oil. We refilled both cavities with the proper weight Bel-Ray oils and checked the air cleaner for proper oiling.

All nuts and bolts were checked for correct torque, spokes were tightened and air pressure set at 12 psi rear, 10 psi front. A couple of people grumbled obscenities about the Pirelli tires and it was time to see if it would run.

A 350cc, 4-Speed, Two-Stroke with a Powerband Equal To a Four-Stroke

The right side kickstarter lever is located slightly above and forward of the front sprocket. It is short (5.5 in.) and the starter's boot heel hits the footpeg after only 6.0 in. of travel. Add a 12:1 compression ratio and starting becomes a jab, jab.

affair. Normally four or five jabs are required to bring the engine to life whether hot or cold.

Anxiety overpowered our desire to be a good neighbor and we gave it the parking lot test. The front wheel leaped into the air in first, and stayed there until fourth was wound out. Wow'. Howr is anyone going to keep the front wheel down long enough to steer?

The next morning found us on Racing World's long, rock-hard, multi-jump southern California course. The ground is so hard that many of the corners and berms are rubber covered. Like a dragstrip starting area.

Because we were not really familiar with the course, we took a Maico 450 Magnum along as a control; we knew what to expect from the Maico. We took a few breák-in laps and then checked spokes and engine bolts for tightness. The engine bolts were fine but the spokes had loosened some.

A novice, intermediate and pro took turns around the snarly track. The suspension was a little stiff but loosened after a few hours. The forks worked well and had adequate travel. The shocks were a different story. Compression damping and spring rate seemed right on, but rebound

damping was too heavy. This caused the back wheel to hop across a quick series of small bumps. Both ends worked well over large jumps and deep rollers though.

The powerband of the motor and the traction at the rear wheel are truly phenomenal. Usable power starts at idle and continues to top rpm. The power curve is flat, gradual and completely controllable. No surges or great bursts, no blubbering, just a steady electric motor-type of power.

The dreaded Pirelli knobbies also proved to be sleepers. Combined with the fantastic powerband, the rear hooked up and gave traction on the hard, slippery parts of the course where no one expected it. The front one worked as well as the back and stuck like glue, although only 46.5 percent of the bike's weight is on the front.

The four-speed transmission shifts smoothly. All of the testers felt the ratios were perfect and more than four gears wasn't needed. With the excellent power and gear spacing, more time can be spent learning the right lines and less thought directed toward shift points. It's hard to be in a wrong gear, but one gear above what seems right gives the fastest times out of corners.

An impromptu drag race between the Maico 450 and Montesa 350 raised a few eyebrows. The Maico was geared for desert, a definite disadvantage. But the Montesa was giving away lOOccs, a bigger disadvantage. The Montesa easily won. We switched riders several times but the results didn't change.

Although the front wheel is very light and can be lofted at any speed, in any gear, it didn't prove to be a problem. By using a higher gear through corners and staying forward on the seat, full power can be used and steering control maintained.

The brakes are strong, progressive, and don't chatter or grab. The footpegs and shift/brake pedals have sawtooth tops, our only complaint being the brake pedal position. It has a height adjuster and the pedal is tucked in tight. Too tight. If the pedal is adjusted low and the cable stretches, the pedal will hit the frame before any braking takes place. This can be corrected by bending the end of it out a small amount, so it clears the frame tube.

After two days of testing, we decided to enter the Cappra in a night motocross at Corona Raceway. Steve Bauer entered the open pro and Donnie Griewe signed up for open novice.

Don won one moto and finished third in the next. On the first lap of the second moto, Don had the brake pedal bottom on the frame. It resulted in a crash and three riders quickly ran over him. Uninjured, he got up and came from last to third (through a large entry), without the use of the rear brake.

Bauer had almost as good a ride. He ran a close second to Rocket Rex Staten in moto one before the stem pulled out of the rear tube. With one lap still to go he rode it flat and managed a third, not bad with fifteen pros entered. A new rear tube and more air (15 psi) allowed Steve to get a second next moto, again behind Staten, as the two ran away from the pack, dicing back and forth for the lead.

continued on page 62

continued from page 58

The back of the bike was visibly rough. The rear wheel wanted to hop over many of the smaller bumps and caused the riders to correct often. Also visible was the traction and quickness of the VB. Nothing in the highly competitive pro class was faster.

Both racers felt the bike competitive, and both said they would change shocks. Works Performance being both's choice.

The bike wasn't fussy and caused few problems. It ran so well right from the crate that no one ever checked the jetting in the 38mm Bing! A couple of small things broke. The "O" ring rubber bands that' hold the shock reservoirs in place are too

flimsy for the job. One side came adrift and thrashed around, breaking the mud splash pan. Hose clamps cured the problem.

The chain tensioner roller disappeared during the same moto but the chain didn't derail. The cold spark plug didn't last long and we replaced it with a NGK B9ES. Add a rear tube to the list, and that's it. The fiberglass gas tank didn't spider web or crack, the fenders are good as new and best of all, it never let us down.

After years of development with basi cally the same engine, Montesa has produced a 350cc engine with a wider powerband than any open bike we can remember. And without the use of.reed or rotary valves. It's amazing that it can give away 50 to lOOccs, not use reeds, and still have competitive horsepower and the widest powerband of any open moto crosser available. With the exception of the shocks, the rest of the bike is equal to the motor: Excellent.

MONTESA VB360

$1795,

The Cappra's magnesium Marzocchi forks are capable performers, but re quire an olt change to derive optimum suspension characteristics. Switching to 5 or 10 wt. oil wilt improve the fork's action considerably and allow full uti lization of long travel and proportional damping rates. Besides remaining oil tight throughout our testing, the stock oil seats offer exceptionally tow friction, and contribute to the fork's overatl sup pleness.

These remote-reservoir Betor units took right on paper, but exhibited a tendency toward packing-down under hard usage. Some may find the rear suspen sion action acceptable as is, but most would benefit by swapping the stock units for a set of aftermarket dampers with medium-hard to hard rates and the stock spring rate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue