YAMAHA SECA 650

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The pendulum, having swung its arc, reaches the top of one swing and halts, then slowly accelerates down the way it came. Passing the apex, it climbs again, this time in the opposite direction, headed upward, upward.

Motorcycling is like that sometimes. We’ve seen Customs and Specials and Low slingers and LTDs introduced and sold and followed by more and more of the semi-chopper genre. We’ve had pullback bars and step seats and teardrop tanks and sissy bars out the ears, turning every street corner into a motorcycle fashion show populated by machines made to be seen, not ridden—at least, not ridden for any length of time.

And now that semi-choppers are commonplace, the motorcycle manufacturers are churning out sport bikes, which have become something different in the sea of semi-choppers, and people are buying them.

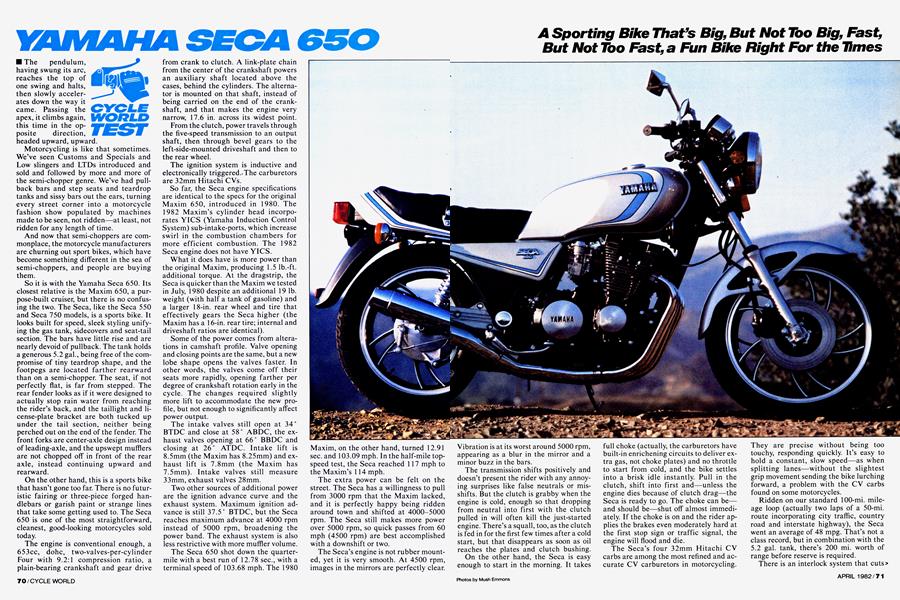

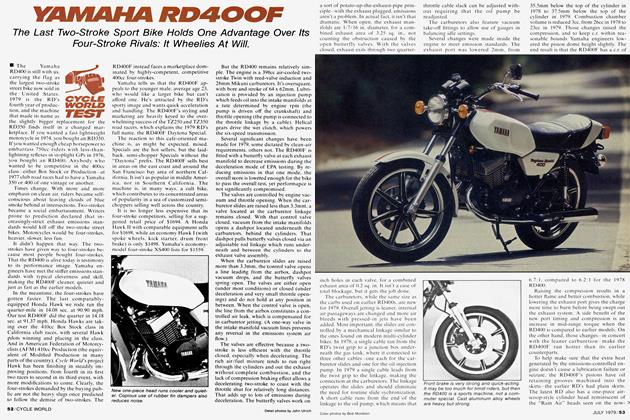

So it is with the Yamaha Seca 650. Its closest relative is the Maxim 650, a purpose-built cruiser, but there is no confusing the two. The Seca, like the Seca 550 and Seca 750 models, is a sports bike. It looks built for speed, sleek styling unifying the gas tank, sidecovers and seat-tail section. The bars have little rise and are nearly devoid of pullback. The tank holds a generous 5.2 gal., being free of the compromise of tiny teardrop shape, and the footpegs are located farther rearward than on a semi-chopper. The seat, if not perfectly flat, is far from stepped. The rear fender looks as if it were designed to actually stop rain water from reaching the rider’s back, and the taillight and license-plate bracket are both tucked up under the tail section, neither being perched out on the end of the fender. The front forks are center-axle design instead of leading-axle, and the upswept mufflers are not chopped off in front of the rear axle, instead continuing upward and rearward.

On the other hand, this is a sports bike that hasn’t gone too far. There is no futuristic fairing or three-piece forged handlebars or garish paint or strange lines that take some getting used to. The Seca 650 is one of the most straightforward, cleanest, good-looking motorcycles sold today.

The engine is conventional enough, a 653cc, dohc, two-valves-per-cylinder Four with 9.2:1 compression ratio, a plain-bearing crankshaft and gear drive

from crank to clutch. A link-plate chain from the center of the crankshaft powers an auxiliary shaft located above the cases, behind the cylinders. The alternator is mounted on that shaft, instead of being carried on the end of the crankshaft, and that makes the engine very narrow, 17.6 in. across its widest point.

From the clutch, power travels through the five-speed transmission to an output shaft, then through bevel gears to the left-side-mounted driveshaft and then to the rear wheel.

The ignition system is inductive and electronically triggered.« The carburetors are 32mm Hitachi CVs.

So far, the Seca engine specifications are identical to the specs for the original Maxim 650, introduced in 1980. The 1982 Maxim’s cylinder head incorporates YICS (Yamaha Induction Control System) sub-intake-ports, which increase swirl in the combustion chambers for more efficient combustion. The 1982 Seca engine does not have YICS.

What it does have is more power than the original Maxim, producing 1.5 lb.-ft. additional torque. At the dragstrip, the Seca is quicker than the Maxim we tested in July, 1980 despite an additional 19 lb. weight (with half a tank of gasoline) and a larger 18-in. rear wheel and tire that effectively gears the Seca higher (the Maxim has a 16-in. rear tire; internal and driveshaft ratios are identical).

Some of the power comes from alterations in camshaft profile. Valve opening and closing points are the same, but a new lobe shape opens the valves faster. In other words, the valves come off their seats more rapidly, opening farther per degree of crankshaft rotation early in the cycle. The changes required slightly more lift to accommodate the new profile, but not enough to significantly affect power output.

The intake valves still open at 34° BTDC and close at 58° ABDC, the exhaust valves opening at 66° BBDC and closing at 26° ATDC. Intake lift is 8.5mm (the Maxim has 8.25mm) and exhaust lift is 7.8mm (the Maxim has 7.5mm). Intake valves still measure 33mm, exhaust valves 28mm.

Two other sources of additional power are the ignition advance curve and the exhaust system. Maximum ignition advance is still 37.5° BTDC, but the Seca reaches maximum advance at 4000 rpm instead of 5000 rpm, broadening the power band. The exhaust system is also less restrictive with more muffler volume.

The Seca 650 shot down the quartermile with a best run of 12.78 sec., with a terminal speed of 103.68 mph. The 1980

Maxim, on the other hand, turned 12.91 sec. and 103.09 mph. In the half-mile topspeed test, the Seca reached 117 mph to the Maxim’s 114 mph.

The extra power can be felt on the street. The Seca has a willingness to pull from 3000 rpm that the Maxim lacked, and it is perfectly happy being ridden around town and shifted at 4000-5000 rpm. The Seca still makes more power over 5000 rpm, so quick passes from 60 mph (4500 rpm) are best accomplished with a downshift or two.

The Seca’s engine is not rubber mounted, yet it is very smooth. At 4500 rpm, images in the mirrors are perfectly clear. Vibration is at its worst around 5000 rpm, appearing as a blur in the mirror and a minor buzz in the bars.

A Sporting Bike That's Big, But Not Too Big, Fast, But Not Too Fast, a Fun Bike Right For the Times

The transmission shifts positively and doesn’t present the rider with any annoying surprises like false neutrals or misshifts. But the clutch is grabby when the engine is cold, enough so that dropping from neutral into first with the clutch pulled in will often kill the just-started engine. There’s a squall, too, as the clutch is fed in for the first few times after a cold start, but that disappears as soon as oil reaches the plates and clutch bushing.

On the other hand, the Seca is easy enough to start in the morning. It takes full choke (actually, the carburetors have built-in enrichening circuits to deliver extra gas, not choke plates) and no throttle to start from cold, and the bike settles into a brisk idle instantly. Pull in the clutch, shift into first and—unless the engine dies because of clutch drag—the Seca is ready to go. The choke can be— and should be—shut off almost immediately. If the choke is on and the rider applies the brakes even moderately hard at the first stop sign or traffic signal, the engine will flood and die.

The Seca’s four 32mm Hitachi CV carbs are among the most refined and accurate CV carburetors in motorcycling. They are precise without being too touchy, responding quickly. It’s easy to hold a constant, slow speed—as when splitting lanes—without the slightest grip movement sending the bike lurching forward, a problem with the CV carbs found on some motorcycles.

Ridden on our standard 100-mi. mileage loop (actually two laps of a 50-mi. route incorporating city traffic, country road and interstate highway), the Seca went an average of 48 mpg. That’s not a class record, but in combination with the 5.2 gal. tank, there’s 200 mi. worth of range before reserve is required.

There is an interlock system that cuts> the ignition system if the bike is put into gear with the sidestand down.

It can be argued that the Yamaha midsize engines—being the 550, 650 and 750 Fours—are the nicest in class. The combinations of compactness and power, smoothness and quick-revving are appealing.

The 650 is aided in its appeal by the chassis. Where the 550 Seca borders on being too small for some riders, the 650’s extra power, longer wheelbase, larger physical size give it just enough more without going too far for a middleweight sport bike.

The frame is conventional, with two downtubes, a main backbone tube and additional lower backbone tubes on each

side. Steel plates reinforce the steering head area. The swing arm pivots on tapered roller bearings and serves as a driveshaft tube on the left side. The center-axle forks are not adjustable and don’t have air caps. The rear shocks are adjustable only for spring preload.

Yamaha believes strongly in shaft drive for street bikes, arguing that the convenience of little maintenance, no mess and long life outweigh weight and cost penalties. The engineers have had years to eliminate torque reactions associated with shaft-drive motorcycles, and they’ve done a pretty good job. The Yamaha’s rear end does not leap into the air when the throttle is opened and doesn’t crash to earth when the throttle is closed. That extra output shaft and the two sets of drive-shaft bevel gears all add to accumulated drivetrain tolerances, though. A

rider just climbing on the Seca is more likely to notice snatch in the drivetrain than shaft drive torque reactions. One rider on his first voyage caught himself making a mental note to lube and adjust the chain when he arrived. A few short trips around town later, the snatch wasn’t noticed at all—once a rider is familiar with the bike, the snatchiness disappears into smoother clutch engagements between gears.

Some extra care must be taken with a shaft-drive Seca on the racetrack, however, since the rear suspension is loaded and unloaded by the driveshaft working against the rear wheel gear. Acceleration effectively raises the rear end slightly and resists compression of the shocks. Steady throttle holds the rear end wherever it is, and resists compression of the shocks. Closing the throttle effectively lowers the rear end and compresses the shocks.

What all this means is that closing the throttle halfway around a turn will reduce available cornering clearance a small amount. That’s nothing to worry about in normal street riding. If the bike’s on a racetrack, the rider’s already hanging off and the footpegs and exhaust pipes are skimming the pavement, slamming the throttle shut mid-turn could cause the bike to high-center on the pipes and lift the rear wheel. The resistance to shock compression could also reduce rear wheel traction if, accelerating hard out of corner, the bike hits a bump and the shocks don’t react quickly enough.

These are problems encountered on a racetrack. One can argue that such things have no bearing on street riding, and certainly we had no trouble with the Seca on most roads. It is also true that a

good rider can easily avoid or compensate for any problems by being smooth, not slamming the throttle open or closed, and by modulating the throttle on bumpy corner exits. If anybody needs proof of that, he can look to the 1981 Seca 750 that finished first 750 in an AFM club endurance race at Sears Point late last year.

Then again, the Seca 650 does not have the same chassis as the Seca 750, and in particular the suspension is simpler and less expensive. Pushed hard on a very tight, twisty, bumpy, rippled country road, the Seca 650 can become a handful. Racetracks are often better thought-out for fast travel than are roads, with superior pavement condition as well. Try to whip the Seca through a bump-stuttered downhill left-right series that requires reducing speed for the second tight corner and the driveshaft torque reaction and its

effect on both cornering clearance and tire traction rears its head as a major problem. Riding the rear brake and keeping the throttle partially open during the transition from left to right helps, but doing that also fades the rear brake quickly. The Seca 650 is happier on smooth pavement and in sweeping turns than it is at speed on cobby roads. Of course, slowing down is one answer.

There have long been arguments over the efficiency of chain final drive vs. a driveshaft. Chain proponents say that a roller chain and sprockets lose less power to friction between countershaft and rear wheel than a driveshaft and associated gears. Driveshaft advocates point out how quickly chain drives lose efficiency without proper attention and lubrication, and engineers at Yamaha further state that testing determined the Seca drive-> shaft to be as efficient in transmitting power as comparable chain drives.

We have had excellent results with Oring equipped chain drives and driveshafts both. But there is no denying that the Seca’s driveshaft requires less maintenance and is neater than a chain. It’s also true that the Seca 650’s dragstrip times are almost identical to those turned by the chain-drive Suzuki GS650.

Another attribute of a driveshaftequipped motorcycle is that wheelbase remains constant. The wheelbase of a chain-driven motorcycle is flexible, being determined at any given moment by chain stretch and positioning of the chain adjustors. The Seca’s wheelbase is 57.1 in. A Kawasaki KZ750 also has a 57-in. wheelbase listed in factory specifications. But take a tape measure out to a parking lot and check 10 KZ750’s and you’ll likely find wheelbases ranging from 57 to 58.5 in.

Taken as a whole, the Seca 650 is fun to ride. The relatively-short 57-in. wheelbase and steep head angle (27.75 ° ) mean it steers quickly and changes direction easily at speed, (although at very low, almost-creeping, parking-lot-space-maneuvering speeds, the steering feels heavy). Cornering clearance is good, and the bike is stable in a straight line and around sweeping turns.

The Seca has dual front discs, each measuring 10.5 in., yet in brake tests the Seca took longer to stop from 30 and 60 mph than did the Maxim, which has a single 11.7-in. disc. It’s true that the Seca is heavier, but it’s also true that the Seca has more brake swept area. The Seca requires a harder pull at the handlebar. After a string of hard stops, a test rider pointed out that he was pulling as hard as he could on the front brake lever, bringing stopping distance from 60 mph down to 138 ft. (the Maxim stopped in 133 ft.). While requiring a strong hand on the lever, the Seca’s brakes are controllable and didn’t lock the front tire unexpectedly—or at all—during tests.

The rear drum brake is unchanged between Maxim and Seca, and both models also have the same style of curved-spoke cast aluminum wheels.

The seating position is comfortable, the almost-flat seat allowing the rider to shift his weight back-and-forth easily on long rides, and the combination of shape and just-right padding makes it an easy sit. The relationship between the seat and pegs is good, too, being slightly rearset but not so much so that the rider’s knees are completely bent and his thighs cramped after an hour on the road. The handlebars are almost flat but do have enough rise to keep the rider’s weight off his wrists, without going to bucko-bar extremes. One nice thing about short handlebars is that it’s easy to change to

slightly higher, slightly-more-pullback bars and still be able to use the standard cables and hoses. Switch a bike with stock bucko-bars to flatter bars and the result is great loops of cables and hoses strung out around the headlight and instruments.

How the Seca’s highway comfort is rated depends upon the yardstick used. The suspension is not as compliant as that found on the Suzuki GS750 or the Kawasaki GPz750, but it is a match for the Suzuki GS650, Kawasaki KZ550 and KZ750.

Since the Seca’s forks don’t rely on air assist to adjust effective spring rate, the fork springs must be stiff enough for sporting use, which compromises comfort on the interstate. The simple shocks also lack damping adjustability. Then, too, the Seca has a relatively short swing arm, as well as the shaft drive’s tendency to resist shock compression under power. The suspension delivers a more comfortable ride than the forks and shocks found on the first Maxim, and ride equal to other bikes of its general dimensions sold without adjustable suspension. But small, repetitive bumps like frost heaves and concrete highway expansion joints do reach the rider.

The Seca comes with a huge (8-in.) quartz headlight with a 55w low beam and a 60w high beam. It throws a wide, bright beam and does a good job of lighting up the roadway. The instruments are simple, consisting of the speedometer, tach, odometer and trip meter, and oil level, turn signal, high beam and neutral lights. Both the speedometer and tachometer are easy to read day and night, and the blue high-beam light is visible without being intrusive. There are no flashing warning lights or fancy LCD gauges, in keeping with the bike’s sporty image.

The controls are straightforward, easy-

to-reach dogleg levers, a front brake master cylinder with a fluid level viewing window, and the normal control pods on each bar. The left-side control pod includes the choke control lever on the bottom, with the horn button just above the choke lever, on the left side of the pod.

When the choke lever is positioned directly below the horn button, it’s difficult to reach the horn button through heavy, insulated gloves. That takes some getting used to, but since the Seca’s choke is best turned off immediately after starting out, the horn button is normally unobstructed.

The dual horns themselves are loud and placed well, bolting to the frame below the fuel tank and facing forward.

The mirrors are rectangular in shape and chrome plated, coming with short stalks to match the stubby bars. Unfortunately, the positioning of mirrors gives the rider an excellent view of his own sleeves and elbows in about half of each mirror’s surface. Keeping an eye out directly behind requires pulling in an elbow and craning the neck to one side.

Tucked away into a small compartment above the swing arm pivot is a small, built-in chain and lock to discourage casual theft of the Seca. The ignition key fits the lock.

The Seca 650 is right at the balance point of motorcycling. Its smaller brother, the Seca 550, is a fun, sporty bike but to some riders it is just a little too small, both in displacement and in physical size. At the other end of the scale, some 1000s and 1100s are a bit too much, a handful cutting through stalled traffic at a crawl, accelerating out of a sweeping turn with the rear tire churning, or even parking in the garage.

The Seca 650 is big enough without being too big, fast enough without being too fast. It’s good sporting fun, a bike that’s right for the times.

YAMAHA SECA 650

$3099

View Full Issue

View Full Issue