KAWASAKI KL250

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Playbike for the Man Who’d Rather Get Home than Go Fast

No sooner had the man from Kawasaki’s test center rolled the KL250 out of his truck than the editor, always ready for a laugh, rolled his Honda XL250 out of the shop and parked it next to the newcomer. “You bring any spares?” he asked. “I’ve bent my shift lever, see, and from the looks of Kawasaki’s entry for the four-stroke dual-purpose Single market, every part will bolt right onto my old nail.”

Even the man from Kawasaki laughed. The four-stroke Single is enjoying a revival. Came time for Kawasaki to offer such a machine in dual-purpose form and Kawasaki designers studied all the needs of the market, the best way to provide this and that, all the techniques for keeping the machine as strong and light as practical, etc. and Kawasaki concluded that Honda’s 1972 bike was close to the answer. So Kawasaki has introduced the KL250 and it’s within a few' inches, a few pounds and one claimed horsepower of the Honda.

That isn’t to complain. Consider it a comment. Maybe even a compliment, as many thousands of riders have bought and enjoyed Honda’s thumpers during the past five years. The concept is a good one.

So is Kawasaki’s update on the concept.

We first became aware of the KL250 upon the arrival of the KZ200. Kawasaki’s road-only Single. The engine looked perfect for off-road work. Remove the electric starter, punch the engine out a bit and it’d be right. The designers did just about that. The KL250 engine is enlarged in bore and stroke (70 x 64mm vs 66 x 58mm for the KZ200), compression ratio was dropped a fraction, 9.0:1 to 8.9:1, and the larger engine got a 28mm Keihin push-pull carburetor, oddly enough mighty like the carb used on the you-know-what. The KL naturally has kick start only and the entire electrical system was changed from 12 to 6 volts, probably to pare off a pound or two.

The KL25Ó engine couldn’t be more conventional. There’s an overhead camshaft working one exhaust and one intake valve in a hemispherical combustion chamber. The valve timing is mild, to make sure there’s adequate power at low engine speeds. The exhaust pipe was carefully done. It sweeps down from the exhaust port and tucks behind the skimpy skid plate until that ends. The pipe is exposed for six inches or so, then curls up into a primary muffler, tucks behind the right-hand shock absorber and runs into a second silencer. The entire system must weigh a bunch, but it does keep sound to a whisper. The exposed portion is at the wrong place, being outside the frame and wider than the skid plate, i.e. the perfect spot for running into rocks.

Two tidy bits. The adjustment for the cam chain is external, at the back of the left side of the cylinder. And instead of a dipstick, the KL250 has a sight gauge, just like the KZ650 and KZ1000. Convenient.

Claimed power is 21 bhp at 8000 rpm. Sounds about right, seeing as the KZ200 is rated at 18 bhp (and the XL250 has 20 bhp. the editor contributes).

What the KL250 is not, is an off-road version of the KZ200. The two models may share a part here and there but the days of fitting high fenders to road bikes and calling them dual-purpose bikes are, thank goodness, far in the past. The KL250 has its own frame, with hefty single front downtube and heftier single backbone, the latter backed up by a second top tube running from steering head to the junction of backbone and the triangulated rear section carrying the swing arm and the loads from the rear shocks. There are no curves in the pipes and every junction is braced or gusseted. Right, it’s heavy. It’s also stiff, which is more important.

There are no major claims for the suspension because it’s all straightforward stuff: center-mount front axle in massproduced forks, mass-produced shocks/ springs angled forward at nearly 45 deg. The KL250 shop manual says front travel is 7.28 in. and rear travel is 4.33 in. Both are close enough to our test figures to be accepted, neither is any great amount when compared to a few other dual-purpose models, for example Yamaha’s DT250 or DT400. Shrug. Kawasaki’s spokesmen are making it crystal clear that the KL250 is a playbike, not an enduro racer or motocross contender. Once again, the fork tubes, sliders, spokes and so forth are substantial and should hold up under hard usage for a long time.

The KL250 of course has full road equipment and like all dual-purpose machines comes with drum brakes fore and aft. There are passenger pegs on the swing arm and one of those nasty straps across the seat, so the KL is legally certified for two people. It’s also about time for the other factories to follow Yamaha and CanAm: The rigid turn signal stalks jutting out from the KL make us nervous just being there, although in fairness all the lights survived a rigorous test. Both sections of the exhaust system have heat shields, so neither operator nor passenger is likely to get burned on the pipe.

The factories have learned a lot during the past five years and the KL250 has properly large front and rear fenders. If there are no claims about unbreakableness, the fenders do seem to be so flexible that it’s hard to imagine breaking one.

Service has been made easier by use of wear indicators for the brakes, the previously mentioned oil level window and by putting the battery and air cleaner behind the side panels below the seat. None of this > lift-up-the-seat stuff. The tool box is just that, a separate compartment below the right side panel. A thief who knows about bikes could quickly depart with the tools, but Honda did much the same thing for the XL series and took no flak then, so Kawasaki can’t be complained at now.

In sum, a nice package. First impression of the KL is highly favorable. Good design for frame and seat has kept the latter’s height nice and low. One cannot say that a 250cc-powered motorcycle that weighs nearly 300 lb. is small, but the KL250 is compact. It feels light and it feels agile. Shucks, what it feels like is a 250 engine in a Honda XL 175 frame.

To repeat a judgment we often make for four-stroke models of this type, the KL250 makes a better road machine than a dirt machine. Getting more personal, we like the KL250 on the road better than we like the KZ200, mostly because the extra 50ccs make themselves known. The KL departs from previous thumper practice in that the steering head rake is 29 deg., compared with 30-32 deg. for the Honda and Yamaha versions of the theme. The KL thus steers quickly and willingly. The short wheelbase helps here, while at the same time there is never any worry about keeping the bike in a straight line at speed. The KL doesn’t have what you'd call speed. It’ll cruise at 60 mph and at that rate, keeping out of the trees requires no more than normal care. The ride is pleasantly firm on normal roads, with something left to soak up the jars of an occasional chuckhole. The KL tends to follow rain grooves some, but that seems to be due to the trials tires.

Vibration? Sure. The grips aren’t soft and the little pegs are steel with cleats, so the rider feels the vibrations, just as he does on any Single. The KL isn’t bad here, though, because the engine is small and vibration comes in proportion to displacement. On pavement the brakes drew mild complaint from one of the road types here. Normal drum brakes is all they are but they will stop the KL within a reasonable distance.

We could have done with a larger fuel tank. The KL carries half a gallon less than the KZ200, damned if we know why. Miles-per-gallon isn’t a problem but when the bike is off the road and working hard, it would be nice to have extra fuel along. We blame the stylists here, as the tank is tapered to match the low and narrow seat.

The seat. On the thin side, for one thing and rather too square for another. Most of the test crew wound up sitting as far back as possible, which puts one atop the strap and takes up most of the space. Two people can squeeze aboard the KL250 but strictly speaking there isn’t room for two adults on rides longer than a mile or so.

Oh, and after a long run on the highway, the KL250 pulls up with no whimper, no clouds of heat from the exhaust pipe and no threats to stick in the manner of smaller sibling KZ200. It’s the engine size, surely. The larger unit is under less stress so it complains not. If you can handle the kick start—and you can; one poke hot or cold— the KL is better in the city or on the highway.

And then we got to ride the KL in the woods. In the KL’s case, the longest test was something of a comparison/torture test: Across a national forest’s summit at 9000 feet, in company with an XT500 Yamaha and the previously mentioned famous-and-immortal XL250 Honda.

The KL250 done good . . . within its limitations. Trials tires work well enough on packed dirt, provided the pressures are reduced from the 21/25 psi recommended for pavement to 15/12 psi off the road.

The KL engine is in what one could call a soft state of tune, with restrictive exhaust and intake systems and a relatively low c.r., the better to use non-lead gas. So while there’s enough power to keep out of traffic’s way and there’s enough power at the top end to keep up on the fire roads, there is not enough power for great bursts of speed at low rpm, which would be nice when you come 'round a turn and find a fallen tree in your path. Or when the road is flat and loose and it would be great to kick the rear wheel sideways under power, just like the big guys except that there isn't enough power to get a slide unless speed is up to where the front end also slides.

The KL steers quite well, thanks to the steep rake. The XT500 owner wondered if such quick response was the best thing for a new; off-road rider to have. The XL owner countered with the claim that for years he’s been experimenting with tires and ride height to get the front-end grip the KL gets at the factory.

The front suspension is fine as is. It could be firmer, but the sliders are of generous length and because travel is limited, there is always plenty of overlap between tube and slider, so the KL’s reaction to bumps and ruts is smooth and predictable. In a way it’s a self-help circle. If the KL could jump higher in the air or ram rocks at speed, why, there’d be need for more travel. Because it can’t, there isn’t.

The rear suspension is adequate. Just. The spring rate must have been chosen for comfort, solo. When the average rider sits down, an inch of travel is used up. We rode with the springs on full preload and still could have used more stiffness.

The rear shocks didn't fade but hot or cold, they lack damping, on compression or rebound. Bottoming is all too easy.

(Curing this last is gonna be a challenge. With an XT500 or XL250/350, you can get more travel with longer shocks. That tips the machine and speeds up front-end response at the same time, good for both models. But the KL already has a quick front. Another degree or so would put it into the trials class, that is, dodgy at 50 or above.)

The exposed section of the exhaust pipe between skid plate and frame isn't exactly exposed. The engineers knew about the problem and there’s a strip of angle iron welded to the pipe where it will strike foreign objects. We did strike them, too, although because we were in the woods, all we hung the bike up on w'as logs. No damage. Instead, a potential for damage.

The exhaust note itself barely exists. You can almost hear the engine in street traffic. Deep in the outback, the pleasant boom of the kitted Honda can be detected ’way off. The clamor of the XT500 announces itself three turns away, but the KL250 could sneak up on Dan’l Boone. Sporting? No. But campers where we had lunch were friendly and impressed with the lack of noise. That has to be a plus.

The KL’s brakes are nicely median. The Honda man was about to complain that the KL’s back was touchy. Then he took a ride on the XT. Ever so much more willing to skid. Put the KL’s front brake down as readily controllable and the rear as needing just a bit of attention.

Well now. The KL250 doesn’t want to wheelie and it doesn’t like to slide. Your average two-stroke playbike of equal displacement will have the KL for lunch. Owners who live where the law allows changes could strip off the signals, install a lighter, less vulnerable and more sporting exhaust. A set of aftermarket shocks and carefully chosen springs would bring the back suspension into the realm of the tolerable. No doubt larger fuel tanks will be on the market shortly.

And at the end of all that a stock twostroke will still have the KL for lunch.

It makes no never-mind to us. Kawasaki has done a good thing here. Your refrigerator will blow' its gasket before the KL does. Your grandmother will go scuba diving before the KL does a mean or unpredictable thing. Later this year we expect to see new' and competitive motocross and enduro models from Kawasaki. One reason we expect that is that the KL is not a racing bike. No intention. No way.

The Kawasaki KL250 is for those of us who want one bike to do all things, if not perfectly then do them well. It’s for fourstroke fanciers, for riders who want to ride into the woods in the morning and out of the woods at the end of the day.

Remember how' the editor got laughs at the beginning of this test?

At the conclusion of the test, the staff surrounded him while he was (still) trying to unkink his shift lever.

“You need a new bike,” they said, “and we know which bike you need.”

If Kawasaki has made another XL250, so has Kawasaki made a better XL250.

KAWASAKI KL250

The KL forks, which incorporate a teflon-coated bearing in the slider, are well suited to the nature of this machine. Adequate travel and acceptable damping rates make for smooth, predictable fork action.

The shock’s slight lay-down angle, combined with an initially low spring rate, provides a soft ride on smooth surfaces. The higher second rate and comparatively high compression damping make the bike work well when the road gets rougher.

Tests performed at Number 1 Products K

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Day the Blue Meanies Stayed Home

January 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

January 1978 By Chuck Johnston -

Short Strokes

January 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

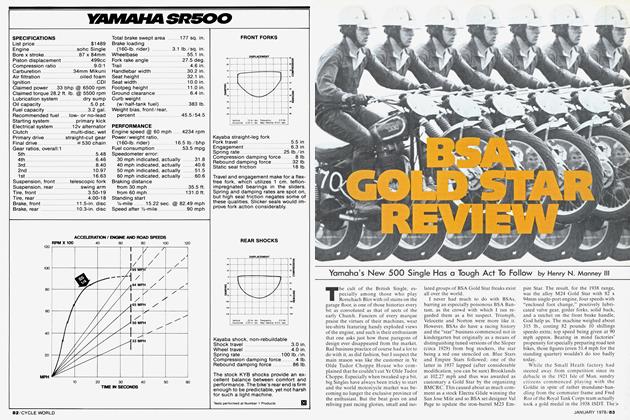

FeaturesBsa Gold Star Review

January 1978 By Henry N. Manney III -

Competition

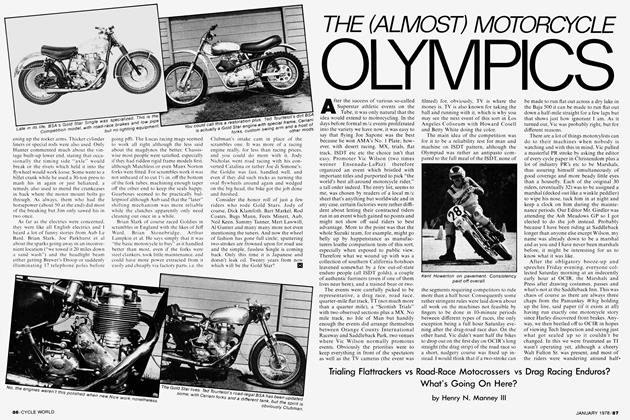

CompetitionThe (almost) Motorcycle Olympics

January 1978 By Henry N. Manney III