TESTING... TESTING... TESTNG

Background and Basics For Our Most Important Product

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM IN the field of enthusiast publications dictates a form of routine disclaimer: When the publication explains how and why it tests whatever it tests, the report is supposed to begin with a few lines about how testing is hard work and it ain’t near as much fun as the readers believe. Balderdash.

Testing is something we do a lot of. Testing is one of our most important products.

And we enjoy it. A lot. We like to look at new motorcycles and talk about them and take them apart and ride them home and around various tracks and take them on trips and so forth. Sure, testing is work. More important, to be sure our tests are

good value for the reader they must first be of value to the testers and they are, mostly because testing is fun to do.

Fine. That reversed routine disclaimer out of the way, we can talk about testing procedures; what they are, why they are that way and what they’re supposed to mean for our audience.

Weights and Measures

MOST OF the data here appears on the test data panel. When we pick up a test bike, new model or improved or whatever. we also get all the literature available for that model. We get an owner’s manual, all the press releases, a shop manual—in short all the literature with all the numbers and claims and instructions.

We spend some time with the men from the factory and sometimes with the people from the factory’s ad agency. We ask what the bike is, and why, and what market they’re after and how they modified an old model or designed a new one.

The motorcycle in question then is trucked to our shop. We strip the outside, for photography and to see how the machine was put together and how the owner is supposed to service the various components.

We measure everything within reach. Wheelbase is checked with the rear axle in the middle of its adjustment. Ground clearance is from a flat floor to the lowest part of the bike at the approximate center of the wheelbase. Peg height is from the floor to the top of the peg. Handlebar width is tip to tip. Seat width is at the widest portion of the area where the median rider would sit, and seat height is from the ground to the center of the same place.

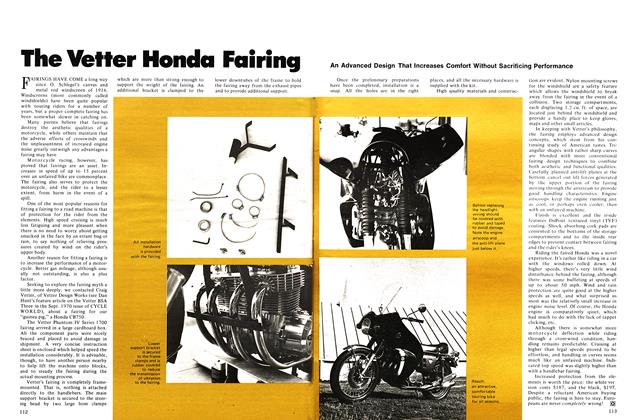

The bike is weighed with half a tank of fuel. We use a certified platform scale and a platform built to match the scale; each wheel is weighed with the machine at dead level. Total weight and weight distribution are computed from this.

Many of the entries in the specifications tables are taken directly from the factory literature, i.e. we accept their word for the various capacities, oil and fuel recommendations, bore and stroke, compression ratio, etc. Ditto for the gearing, except for some of the limited-production machines. Those makers have no literature so the testers remove the side covers and count all the teeth.

The gearing computations are done by multiplying the primary drive ratio by the final drive ratio by the ratios for each speed in the transmission.

Engine power has long been a point of contention. Time was, the factories made exaggerated claims for power. Currently many of the manufacturers make no claim at all. When there is a figure, we usually print it and identify it as a factory claim. If there is some controversy,we might test the engine on a dynamometer. Most of the time we do neither.

Reasons? Mostly because we have better ways to provide better information. A dyno test chart is a piece of paper. A time and speed for the standing quarter mile or the bike’s top speed are facts. If the bike is quick, the engine output is moot. If it isn’t quick, knowing the dyno results is no comfort.

For suspension testing, we go the other way, further than anyone else in the testing business.

Times to speed and distance are factual. So far there is no truly objective test for handling. The crew can report that the forks feel stiff or that the rear shocks seemed to fade a bit after running hard for a couple miles. The reader gets nothing from this; stiff, faded, rough, etc., are purely subjective.

One fork leg and one shock/spring are removed from each test bike and taken to the Number One Products lab, where the unit is strapped into, well, we call it a shock dynamometer but it’s more than that.

An engine dyno records the engine’s actions, that is, the engine produces force and the dyno measures the force.

The shock dyno records reactions. The fork leg or shock/spring is bolted into place and subjected to a standard sequence, programmed to duplicate actual riding conditions. It’s also programmed to be easily repeated.

This standard sequence delivers a graph, in which the testers can see what happens to the unit under test. We can measure seal drag, initial dampening, and rebound dampening in the middle of the stroke and at each end.

This looks complicated. The actual shock dyno is complicated. The results are useful numbers, used to interpret what happens to the unit and what that will mean on the bike.

What all this means is first, we can be objective. We have facts. We can say the forks in question have a relatively high initial resistance, due to seal drag. We can say the springs are stiffer than those usually found in a motorcycle of this type and weight, or that compression damping has been reduced, compared to the previous model, while rebound damping has been increased. It may be that 30 minutes of cycling through the unit’s full travel at speed under load reduced the shock to jelly. The shock may leak, or its shaft may bend. We seldom test to destruction, but if our normal loading does destroy the unit, so be it, and so shall the test report talk about it.

Pure science isn’t enough. After the dyno testing we have an objective graph and chart. If the rear wheel begins to hop on the motocross course, or if each ripple in the highway gets the rider in the teeth, we can comment and tell the reader what happens and why. No guesswork, no personal feelings. As an extra bonus, because we know where each test unit is strong and where it’s weak, we can make valid recommendations for fixing or reducing the problem.

The best part of this system is its repeatability. A trail or motocross course changes constantly. The suspension dyno never changes. Each unit can be subjected to exactly the same test and each can be measured against a constant.

The Formats

THAT’S THE hard work portion of the tests. From this point, with the lab examinations completed, the tests differ on the basis of the machine’s intended purpose.

There are two basic divisions; roadlegal or off-road.

Every test bike which can be legally registered for use on public highways goes to a drag strip. Acceleration runs are made with an expert rider and with the bike in normal and stock tune, carrying half a tank of fuel. The runs are made in standard drag-racing style, that is, the bike is staged and run in conjunction with the strip’s certified clocks. We’re careful not to abuse the machine. At the same time, the nature of this testing and of the riders ensures that each test bike, of whatever brand and engine size, will be ridden to its maximum. We run until the times are consistently quick.

A note on comparisons: Every testing organization, public or private, in-house or publication or whatever, develops its own techniques. These techniques differ Obviously we believe ours are the best. But. If a CYCLE WORLD test shows a quarter-mile time of 13.0 sec. and the manufacturer or somebody says the same model did 12.8 sec. or 13.2 sec., that doesn’t mean our riders are better or worse than theirs, or that we or they are lying. Chances are they use different methods. Comparisons should be limited; if CYCLE WORLD says Brand A’s 500cc roadster turned 13.0 sec. and Brand B’s did 13.2 sec., we’re saying we found one model to be quicker than the other model. If somebody else has different times, that’s no concern of ours.

The drag strip is also used to calibrate speedometers. The bike is ridden through the timing lights at indicated speeds. Those speeds are compared with timed speeds, i.e. indicated 40 mph is actually 36 mph, indicated 50 is 45, indicated 60 is 53 and so on. With these spaced corrections we can build a curve showing speedometer error. With speedometer error allowed for, we can test brakes. Our system is two allout stops, maximum braking under complete control, from 60 mph and 30 mph.

The actual measuring is the work of a device which bolts to the test bike. A hammer, electrically triggered by the brake light circuit, fires a chalk pellet onto the pavement. We thus know when the brake was applied and measure from the chalk mark to the pellet gun on the stopped bike to get braking distance.

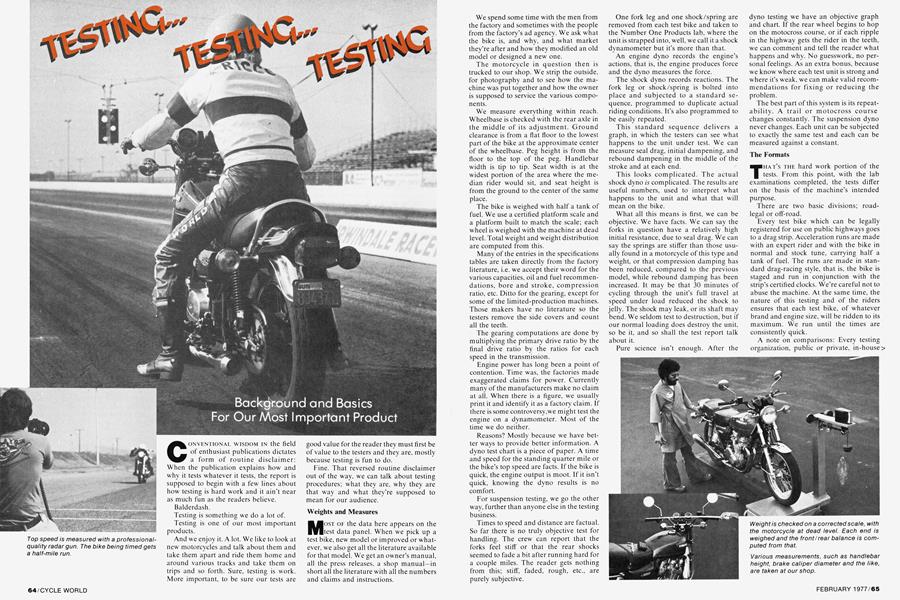

Top speed is checked with the aid of a radar gun, right, the kind the police use. The test motorcycle is run at least half a mile, and flashes down the straight while another tester stands too close to the center line and points the radar gun. Simple and accurate. Our timed speed figures would hold up in court, so to speak.

The final work at a race track is an option. We usually use just the drag strip. A high performance road machine may have more speed and cornering potential than can safely be tested on the public road, so for such a machine we’ll schedule an extra day at a road race course, generally Riverside or Willow Springs.

The first actual road testing involves fuel consumption. Miles per gallon is a good yardstick for cost of operation and engine efficiency. Because of this, the test is carefully controlled. The test bike is topped off at our neighborhood fuel stop, then ridden around a long road loop, part interstate highway, part open country, part city streets. It’s filled with fuel again, to exactly the same level.

As they say in the small print, the actual mpg you get depends on where and how you ride. Our test doesn’t include cold starts, or stop and go, or hour after hour of steady cruising, so the test figures will be higher than some and lower than others. No problem. Just as with the drag strip times, the test figures are for comparison against our other tests and not against what any owner or factory claims to get.

Along with the normal one-model road test, CYCLE WORLD does full comparison testing of competing models in the same general class, that is, dual-purpose 250s, large touring bikes, etc.

Each example in a comparison test gets the full treatment at the strip and the shop, but instead of going ’round the mpg circuit one at a time, the entire staff will take the group on a long ride, with mass fuel stops. Again, this is comparison testing and it may happen that the Yamonda 750 we tested by itself didn’t get the same mpg when tested as part of a group.

In the Dirt

THE DIFFERENCES between road testing and off-road testing are considerable, for two main reasons. First, while pavement is the same, day after day, dirt is always changing. Acceleration and braking distance are repeatable, time after time, which means quarter-mile times for one bike this month can be fairly compared with another bike next month. This doesn’t work for lap times at the motocross course or distance covered at a steep hill.

Second, dirt bikes vary widely in intent. Because there are specialized activities, i.e. trials, enduros, desert racing, woods riding and motocross, there are specialized machines for each and few work well taken out of context.

Because test conditions off road can’t be exactly duplicated from one day to the next, we don’t try for definite figures off road, just as it makes no sense to report miles per gallon on a motorcycle which doesn’t have an odometer and isn’t expected to go more than a 40-minute moto or 40-mile loop without stopping for more fuel.

Instead, we test on the basis of intent; if it’s a motocross racer, we take it to a motocross course and several good riders do their best and report in detail on where the bike does well and where it doesn’t. Enduro machines are ridden over enduro courses, trials bikes go through trials sections, playbikes go camping over the weekend and so forth.

Because of our suspension testing program, we can compare the important components against each other. Perhaps more useful, the test riders can make accurate comments about why the front wheel washes out or why the rear wheel skips about under load, leading to educated estimates as to how these flaws can be made right.

Two important exceptions to the above: In a comparison test of off-road motorcycles, times are taken and the bikes are definitely compared against each other. Motocross models are raced, with riders rotating in sequence. Then we can give lap times, best and average. Beyond that, a group test usually involves hillclimbs, whoop-de-doos and so forth, also time, as a basis for reporting that the Brand X 250 has more power while the Brand Y 250 is quicker over the jumps.

Dual-purpose bikes get the full treatment. They’re ridden offroad, usually under enduro conditions, trials sections, everything we can throw at them. The same machines are given the full road examination as well. If a motorcycle can be licensed and used on the public highway, we do it and we report acceleration times, braking distance, miles per gallon, the complete package.

The Text

THE ENTRIES on the various data panels and specification tables are fact.

The text, that is the words and descriptions and reactions and conclusions are collective judgements.

Text copy generally includes a short history of the model in question, or of the model’s predecessor’s if it’s new. We’ll detail what the manufacturer has done, in the technical and marketing senses, and we’ll tell what they expect the bike to do, both in terms of performance and of sales and image.

We also include what we believe are informed opinions, i.e., the factory hopes this bike will sell to commuters and we do/ don’t agree the machine will do the job.

The text is the place to mention clever work. There’s nothing on the data panel to explain Yamaha’s self-cancelling turn signal’s or Kawasaki’s starter motor lock-out or Husky’s automatic transmission. The text can give credit where due.

And the text can criticize. Some of the criticism is technical. The shocks may tire too quickly, or the battery not be strong enough for the engine. More likely these days, there will be human engineering problems like a seat that’s too soft or a kill switch hidden beneath the wiring loom. The text is where we register complaints.

Collective judgements. Our purpose is to report on motorcycles, from a base of enthusiasm and experience and from a viewpoint of keeping the purpose of the test bike constantly in mind.

Objectively, this means not complaining if a commuter scooter doesn’t offer blazing quarter mile times or if a trialer shakes its head at top speed. Fair is fair.

Subjectively, every test rider in this office owns at least one motorcycle. No two staff-owned bikes are the same. We don’t agree with each other as to which make and model is best.We haven’t yet found the perfect motorcycle.

But we all can enjoy the search. EH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1977 -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1977 -

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Twins And Triples

February 1977 By Len Vucci -

Competition

CompetitionGoing For the Big 1

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs -

Competition

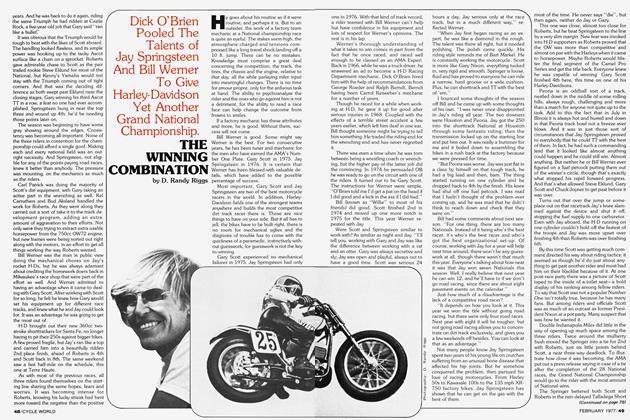

CompetitionThe Winning Combination

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs