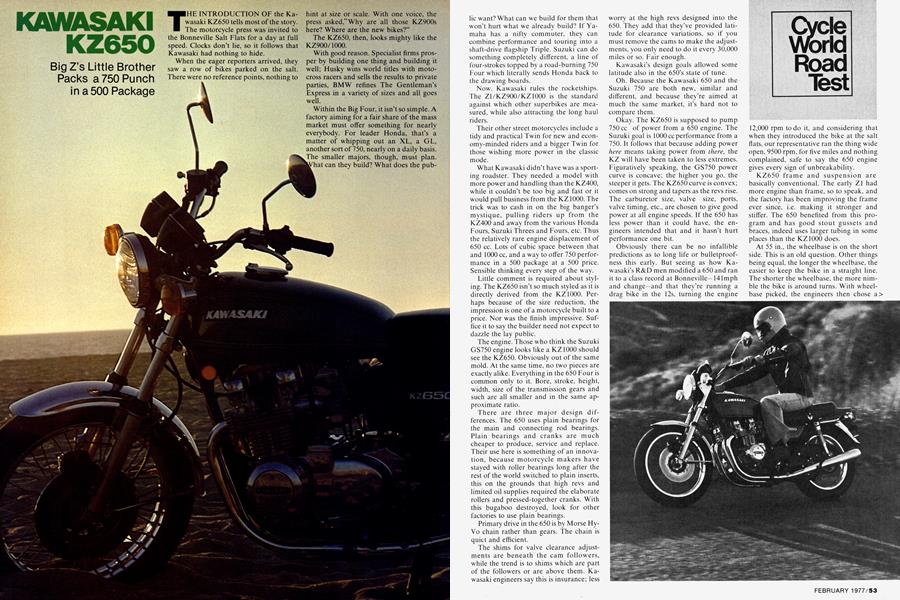

KAWASAKI KZ650

Big Z's Little Brother Packs a 750 Punch in a 500 Package

THE INTRODUCTION OF the Kawasaki KZ650 tells most of the story. The motorcycle press was invited to the Bonneville Salt Flats for a day at full speed. Clocks don’t lie, so it follows that Kawasaki had nothing to hide.

When the eager reporters arrived, they saw a row of bikes parked on the salt. There were no reference points, nothing to hint at size or scale. With one voice, the press asked,“ Why are all those KZ900s here? Where are the new bikes?”

The KZ650, then, looks mighty like the KZ900/1000.

With good reason. Specialist firms prosper by building one thing and building it well; Husky wins world titles with motocross racers and sells the results to private parties, BMW refines The Gentleman’s Express in a variety of sizes and all goes well.

Within the Big Four, it isn’t so simple. A factory aiming for a fair share of the mass market must offer something for nearly everybody. For leader Honda, that’s a matter of whipping out an XL, a GL, sort of 750, nearly on a daily basis. The smaller majors, though, must plan, hat can they build? What does the publie want? What can we build for them that won’t hurt what we already build? If Yamaha has a nifty commuter, they can combine performance and touring into a shaft-drive flagship Triple. Suzuki can do something completely different, a line of four-strokes topped by a road-burning 750 Four which literally sends Honda back to the drawing boards.

Cycle World Road Test

Now. Kawasaki rules the rocketships. The Z1/KZ900/KZ1000 is the standard against which other superbikes are measured, while also attracting the long haul riders.

Their other street motorcycles include a tidy and practical Twin for new and economy-minded riders and a bigger Twin for those wishing more power in the classic mode.

What Kawasaki didn’t have was a sporting roadster. They needed a model with more power and handling than the KZ400, while it couldn’t be too big and fast or it would pull business from the KZ 1000. The trick was to cash in on the big banger’s mystique, pulling riders up from the KZ400 and away from the various Honda Fours, Suzuki Threes and Fours, etc. Thus the relatively rare engine displacement of 650 cc. Lots of cubic space between that and 1000 cc, and a way to offer 750 performance in a 500 package at a 500 price. Sensible thinking every step of the way.

Little comment is required about styling. The KZ650 isn’t so much styled as it is directly derived from the KZ1000. Perhaps because of the size reduction, the impression is one of a motorcycle built to a price. Nor was the finish impressive. Suffice it to say the builder need not expect to dazzle the lay public.

The engine. Those who think the Suzuki GS750 engine looks like a KZ 1000 should see the KZ650. Obviously out of the same mold. At the same time, no two pieces are exactly alike. Everything in the 650 Four is common only to it. Bore, stroke, height, width, size of the transmission gears and such are all smaller and in the same approximate ratio.

There are three major design differences. The 650 uses plain bearings for the main and connecting rod bearings. Plain bearings and cranks are much cheaper to produce, service and replace. Their use here is something of an innovation, because motorcycle makers have stayed with roller bearings long after the rest of the world switched to plain inserts, this on the grounds that high revs and limited oil supplies required the elaborate rollers and pressed-together cranks. With this bugaboo destroyed, look for other factories to use plain bearings.

Primary drive in the 650 is by Morse HyVo chain rather than gears. The chain is quiet and efficient.

The shims for valve clearance adjustments are beneath the cam followers, while the trend is to shims which are part of the followers or are above them. Kawasaki engineers say this is insurance; less worry at the high revs designed into the 650. They add that they’ve provided latitude for clearance variations, so if you must remove the cams to make the adjustments, you only need to do it every 30,000 miles or so. Fair enough.

Kawasaki’s design goals allowed some latitude also in the 650’s state of tune.

Oh. Because the Kawasaki 650 and the Suzuki 750 are both new, similar and different, and because they’re aimed at much the same market, it’s hard not to compare them.

Okay. The KZ650 is supposed to pump 750 cc of power from a 650 engine. The Suzuki goal is 1000 cc performance from a 750. It follows that because adding power here means taking power from there, the KZ will have been taken to less extremes. Figuratively speaking, the GS750 power curve is concave; the higher you go, the steeper it gets. The KZ650 curve is convex; comes on strong and tapers as the revs rise. The carburetor size, valve size, ports, valve timing, etc., are chosen to give good power at all engine speeds. If the 650 has less power than it could have, the engineers intended that and it hasn’t hurt performance one bit.

Obviously there can be no infallible predictions as to long life or bulletproofness this early. But seeing as how Kawasaki’s R&D men modified a 650 and ran it to a class record at Bonneville—14lmph and change—and that they’re running a drag bike in the 12s, turning the engine 12,000 rpm todo it, and considering that when they introduced the bike at the salt flats, our representative ran the thing wide open, 9500 rpm, for five miles and nothing complained, safe to say the 650 engine gives every sign of unbreakability.

KZ650 frame and suspension are basically conventional. The early Z1 had more engine than frame, so to speak, and the factory has been improving the frame ever since, i.e. making it stronger and stiffen The 650 benefited from this program and has good stout gussets and braces, indeed uses larger tubing in some places than the KZ1000 does.

At 55 in., the wheelbase is on the short side. This is an old question. Other things being equal, the longer the wheelbase, the easier to keep the bike in a straight line. The shorter the wheelbase, the more nimble the bike is around turns. With wheelbase picked, the engineers then chose a> steering head angle to let the stable bike steer and the nimble bike go straight. The Suzuki GS750 has a wheelbase three inches longer than the 650’s, while both use a steering head angle of 27° off vertical. (For further comparison, the KZ1000 is longer, with a 59-in. wheelbase, and has one degree less rake.) Anyway, and despite knowing that the GS750 is designed more for touring than is the KZ650, we can expect the Suzuki to excel in a straight line and the KZ650 to enjoy being pitched through curves.

Ah. Include weight in that equation. The 650 is roughly 15 lb. lighter than the GS750. Weight affects what a motorcycle does; even more, it affects how a motorcycle feels.

Speaking of conventional, the KZ650 has wire wheels, disc brake in front, drum in the rear and a four-into-two exhaust system, of which we are seeing many at present. Like the other production Fours and unlike the Hooker system tested elsewhere in this issue, the KZ650 layout pairs the cylinders on the basis of location rather than timed exhaust pulses.

We need a better word for the other items on the KZ650’s standard equipment list. Terms like gimmick and gadget have a critical tone and apparently there are many people who welcome certain extras. Yamaha provides a thumbnail-size computer to turn off your turn signals, Suzuki gives you red instrument lights and digital indicators for gear in use, and Kawasaki provides a panel light to tell you the brake light is on, and a switch to cancel the starter button unless the clutch lever is pulled in. All of them clever, and none of them things a motorcycle really needs.

The above pretty much describes what the KZ650 is, and why. Time now for what it does.

Kawasaki’s advertising campaign has become something of a problem, in that the headlines speak of out-performing all the 750s on the market. This became blurred with the arrival of the GS750, as Kawasaki personnel suddenly became keen on defining performance as a blend of various attributes. Ride comfort, handling, miles per gallon, in short, a list of qualities, some of which are subjective. Gee. All this time we thought performance was a matter of elapsed times for the standing quarter mile.

A shame we got hooked on this. For the first thing, the KZ650 is damned quick, for a 650, or a 750, or any motorcycle with any displacement. An elapsed time of 13.19 seconds puts the KZ650 in fast company indeed.

Took some practice, though. The KZ 1000 needs to have its power controlled with the clutch or the torque goes up in smoke. The GS750 needs clutch slip and high revs because it doesn’t have surplus torque.

The KZ650 has some torque, but no surplus. You can light the tires. You can bog the engine. And you can also hook the power hard to the ground and because the bike is short, up comes the front wheel. If it comes up just enough, meaning all the weight is doing maximum good and the engine is on the cams exactly right, it’s gonna be a good run. If the wheel really comes UP, backing off is the only solution.

Be that as it may be, the KZ650 will run with the average 750. And our test, as carefully controlled as we can make it, shows a slightly slower time for the KZ650 than for the Suzuki GS750.

In real life, one is seldom called upon to engage in such contests of speed, so of more true value here is that the KZ650, being tuned for brisk performance rather than blazing power, is smooth and delightful at all speeds. Winter starts can be an annoyance because the ratio of enrichment vs faster idle seems biased in behalf of enrichment. You can’t speed it up without choking it down.

For the rest, there are no flat spots, or even weak spots. The 650 is strong all the way to redline. There’s power to pass without needing to downshift—although shifting down does help. The 650 is remarkably smooth below 5000 rpm. The mirrors are clear as glass, a trait so rare we had to think hard before realizing what was different. Over 5 thou, they buzz into uselessness. That will either be no drawback or it will subtract the mirrors when you need them most, depending on rider style.

Noise level is low. There is not much exhaust note. Intake hum is also quiet. Mostly the sound is a mix of gears and pipes and chain and tires. Oddly, the sum of this at 40-50 mph is enough to seem as if there’s another gear left to go. From 55 mph up to normal highway cruising with traffic, i.e. 60-70, the noise is somehow left behind and the loudest sound is the wind whistling around your helmet.

The KZ650 clutch is the KZ1000 clutch, minus two plates. More than enough for the task. Smooth, too, with a nicely progressive engagement. The entire drivetrain is the same. This begins with the primary drive. Gear-to-gear is abrupt and the factories must compensate for this with plenty of slack and padding in the mountings and cush drive. The Hy-Vo chain is itself a cushion, so there is less jerk to compensate for and the combination works soft as can be. The throttle is on the light side for a Four. All in all, one can slip into motion in traffic or blast away in the wide open spaces minus embarrassing lurch. Good.

Our braking evaluation may have suffered some through Kawasaki’s generosity. The press met the bikes at the salt flats, then went touring and had time for some hot laps at Fuji Speedway, the better to know how well the KZ650 performs.

The stopping figures and lack of fade in our normal test sequence are excellent. Thing is, we know from time on the race track that if a fast rider really pushes the bike into every corner, the front disc and rear drum will both lose some of their edge. Not completely, but the fast overthe-road man may need to note that after a few stops at one “g,” the bike will need a bit less speed or a few more feet to get slowed.

KAWASAKI

KZ650

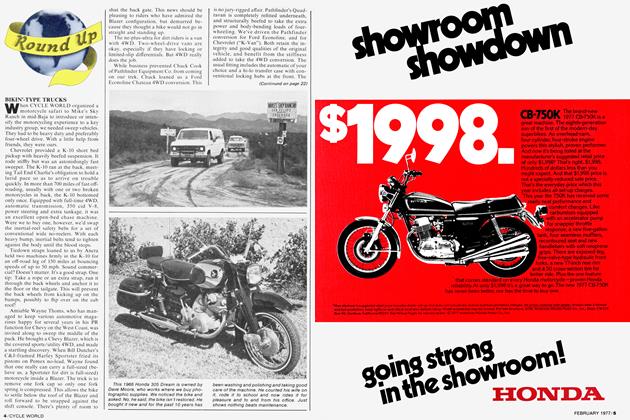

$1995

As a function or result of the short wheelbase, under maximum braking with the front wheel right on the verge of locking, weight transfer gets the rear wheel light and the bike’s tail wags. To repeat, this is also at full chat. In daily use, the brake leverages front and back are nicely balanced, requiring firmness but not a Grip of Steel.

Suspension is a matter of progress in small steps. The suspension dyno shows a surprisingly low initial seal drag, in the Yamaha vein although far as we know the Kawasaki seals are normal material rather than teflon. Damping and spring rates are about what any big manufacturer would fit, that is, the ride is on the soft side while still allowing fast riding or two people aboard. Not both at once, by the way. With passenger or even with a heavy rider, say 200 lb. or so, the KZ650 can be scraped. This is through weight, not speed. During the track tests the group’s only 200lb. man touched down every lap at one tight hairpin. The others in the party never scraped anywhere and the laps times were comparable. In any case, stiffening or a higher ride height to make sure no rider would every touch would hamper the machine in other, more usual, circumstances.

The actual valving and oil capacity of the shocks and forks are no better than they need to be. They do their job. The ride is good and the handling is also good. There could be more control and they could work better when hot, but that’s an area about which much criticism has been aimed with not much effect, so if you wish to take corrective steps, check with the aftermarket folks, don’t write to the factory.

Besides, what you get from the factory is a enormously satisfying roadster. Brisk performance, good brakes, smooth ride and all that. The keen part here is the lack of weight. Fifteen lb. less is a lot less for a> motorcycle. The overall design is supposed to be ridden with spirit. The lack of bulk means it can be done. A shift of the body, a flick of the bars and the KZ650 lays into the optimum cornering line sure as water runs downhill. The feeling is that the KZ650 is willing to follow orders in spots where a heavier machine would need to be muscled into cooperation. And the same feeling of control applies to city work, which we all must cope with at times.

FRONT FORKS

Description: Kayaba fork, HO• 315 oil Fork travel, in.: 5.5 Engagement, in: 7.0 Spring rate, lb./in.: 40 Compression damping force, lb.: 9 Rebound damping force, lb.: 33 Static seal friction, lb.: 10

Remarks: The KZ650 Kawasaki is without question the best handling, softest riding Kawasaki to date. To achieve the soft ride, (which aids in control on normal street surfaces), Kawasaki has drastically reduced compression damping and static seal friction. Kawasaki still uses a fairly stiff spring but has reduced preload which allows the forks to react to seams on concrete freeways, and the like. This spring setup also minimizes nose diving while braking. Wheel travel is more than adequate for a road bike and there is sufficient fork engagement for stable handling. Rebound damping is mar* g~natIy tight, but is not worth changing. Tourina riders should use 10 weiaht oil. Those wanting optimum handling should use 20 weight.

Tests performed at Number One Products

REAR SHOCKS

Description: Kawasaki rear shock, gas/oil mix, non-rebuildable Shock travel, in.: 3.25 Wheel travel, in.: 4.0 Spring rate, lb./in.: 86 Compression damping force, lb.: 8 Rebound damping force, lb.: 86

Remarks: Like the front forks, the KZ650 rear shocks have minimal compression damping. This, in combination with an 86 lb. spring, yields a very soft ride. Rebound damping is again, marginally light (as in the forks). Touring riders will like this shock. Optimum handling can be obtained by fitting a shock with more oil capacity. More oil capacity, in general, means more consistent damping because there is less heat build up. A good choice is Koni. The stock spring rate is fine.

By means of comparison, the design predictions come true. The KZ650 has at least as good (read as stiff) a frame as does the Suzuki GS750. The longer and heavier GS is more stable at top speeds, where keeping straight is of prime importance. The KZ650 has a slight edge in the tight stuff, any place weight works against results. If forced, we’d give the smallest possible vote in favor of the overall handling of the GS, mostly because the swinging arm and rear shocks feel as if they do just that much better work. Close, though, close enough to be a matter of where and how the rider does his stuff.

Accommodations are, for the most part, very good. The seat is filled with some manner of bionic foam with rising-rate compression, if there is such a word. Theory is, the padding is soft initially and becomes firmer as it’s compressed. Fine idea and that aspect of the KZ650’s saddle makes it equal or better than any other on the market.

But a glance will show that the 650’s saddle is in two distinct planes. This is an old racing trick, or a custom trick. Two clear gains. First, the rider portion of the seat is low, so riders of average height or less can put their feet on the ground without strain. Second, the ridge where the first half rises to become the second half provides a handy stopping point. Keeps you in place under full power, which is why the racers do it and not a bad thing to have.

As a possible benefit, if the rider’s seat curves exactly where the motorcycle’s seat curves, the step is a contour. Takes some of the rider’s weight off what can truly be described as his bottom.

The flaw is that when Kawasaki breaks the seat level into two steps, they are telling the rider where to sit and where not to sit. One influence is how tall the occupant is. Another is personal style. Some bikers sit bolt upright, some slouch into a motocross curve with torso forward and arms and back bent. And some use the road-racer’s V, well back on the bike, leaning forward.

Road racers will have trouble with the KZ650 seat. You must be in one place or the other and you can’t sit in between. Too bad. Those who sit where Kawasaki expects them to can go for hours. Those who like another posture will be less comfortable unless they get used to their new location. Strange place to become dictatorial, especially when in all other ways the saddle itself is so good. Right, a quick trip to the upholstery shop and you have a one-plane seat with bionic padding.

Other ergonometrics are first rate. The short wheelbase puts the rider fairly close to the bars, which in turn can be far apart, high and reasonably narrow. In the case of our testers, the grip angles were fine, the grips were no firmer than everything else from the big manufacturers and even the pressure from the throttle return spring was light for a four-carb engine. The switches are perfectly normal and work without notice. Except maybe for the headlight switch, noticed because there is one. Refreshing to have that decision left to the rider.

The fuel tank looks wider than it feels. The rider pegs are an inch or so too far forward for sports riding, evidently because there isn’t extra room on the back and the designers reckoned the rider’s heels should stop before the passenger’s toes begin. The engine vibration which shook the mirrors at speed did less to the pegs. Something to do with mounting points, no doubt. Passengers report the ride back there is fine, albeit one cannot lounge about. The engine has the suds to pack two and while the extra weight will lower the bike enough to risk grounding, it comes at cornering speeds sufficient to discourage the average passenger anyway and we all know what happens when she thinks you’re going too fast, don’t we? No sense worrying about ultimate cornering clearance with two up, then.

In sum, Kawasaki has done more than fill a gap in the market line-up. No matter how you define it, the KZ650 does offer 750 performance in a more sporting package and for a few less bucks. The KZ650 has the visual appeal of its big brother and because the chassis is at least equal to the engine, the 650 has agility and a sporting feel to compensate—or better—the sheer speed of the KZ1000.

One of the more painful cliches in the testing business is where the report concludes with some fatuous remark about how we hate to give it back.

We wouldn’t say a thing like that. Instead, we aren’t going to give it back. We are negotiating with Kawasaki for permission to keep the KZ650. The official reason is to allow a 10,000-mile extended test; how else can we evaluate this new model? Among ourselves, though, we intend to keep the KZ650 because it’s fun to ride.0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1977 -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1977 -

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Twins And Triples

February 1977 By Len Vucci -

Competition

CompetitionGoing For the Big 1

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs -

Competition

CompetitionThe Winning Combination

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs