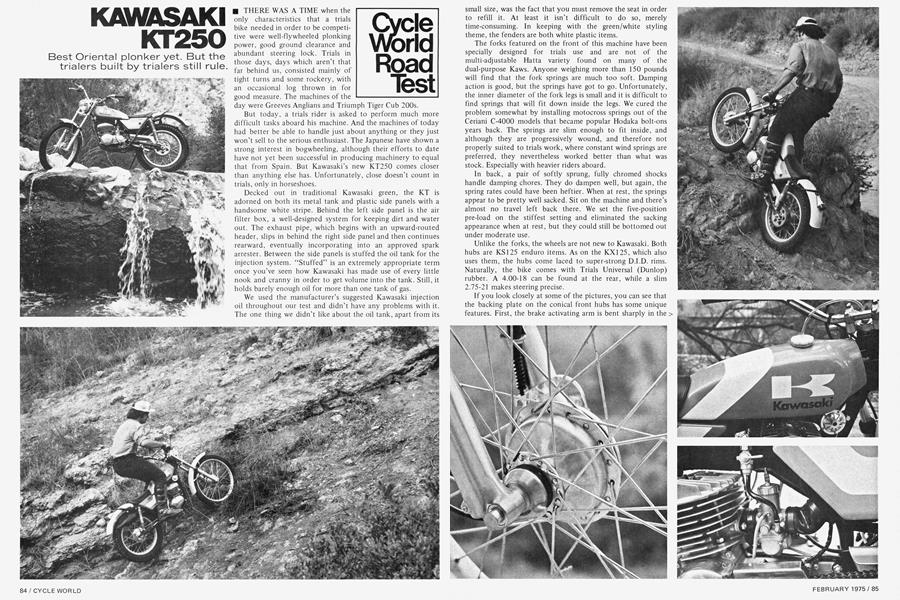

KAWASAKI KT250

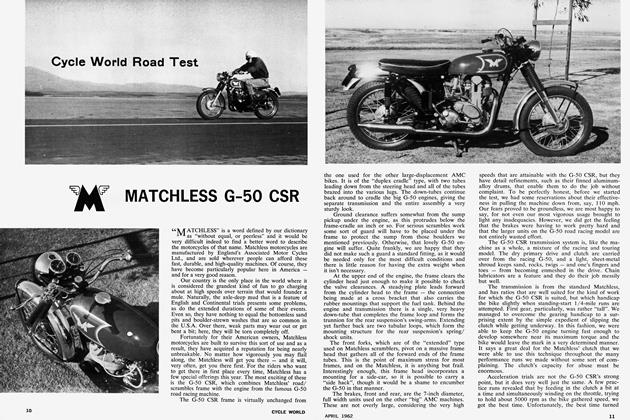

Cycle World Road Test

Best Oriental plonker yet. But the trialers built by trialers still rule.

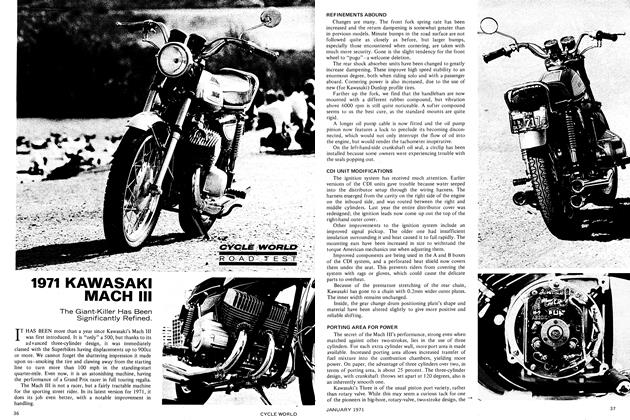

THERE WAS A TIME when the only characteristics that a trials bike needed in order to be competitive were well-flywheeled plonking power, good ground clearance and abundant steering lock. Trials in those days, days which aren’t that far behind us, consisted mainly of tight turns and some rockery, with an occasional log thrown in for good measure. The machines of the day were Greeves Anglians and Triumph Tiger Cub 200s.

But today, a trials rider is asked to perform much more difficult tasks aboard his machine. And the machines of today had better be able to handle just about anything or they just won’t sell to the serious enthusiast. The Japanese have shown a strong interest in bogwheeling, although their efforts to date have not yet been successful in producing machinery to equal that from Spain. But Kawasaki’s new KT250 comes closer than anything else has. Unfortunately, close doesn’t count in trials, only in horseshoes.

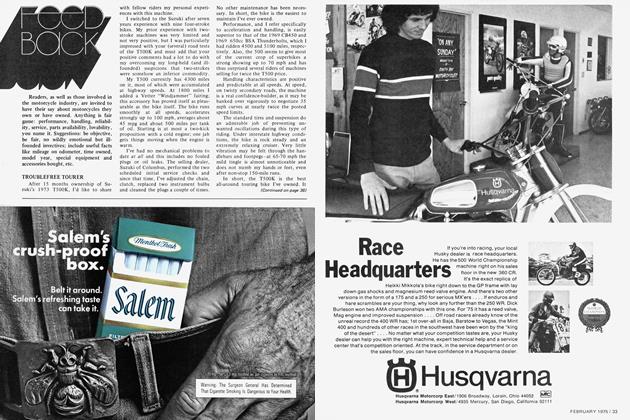

Decked out in traditional Kawasaki green, the KT is adorned on both its metal tank and plastic side panels with a handsome white stripe. Behind the left side panel is the air filter box, a well-designed system for keeping dirt and water out. The exhaust pipe, which begins with an upward-routed header, slips in behind the right side panel and then continues rearward, eventually incorporating into an approved spark arrester. Between the side panels is stuffed the oil tank for the injection system. “Stuffed” is an extremely appropriate term once you’ve seen how Kawasaki has made use of every little nook and cranny in order to get volume into the tank. Still, it holds barely enough oil for more than one tank of gas.

We used the manufacturer’s suggested Kawasaki injection oil throughout our test and didn’t have any problems with it. The one thing we didn’t like about the oil tank, apart from its small size, was the fact that you must remove the seat in order to refill it. At least it isn’t difficult to do so, merely time-consuming. In keeping with the green/white styling theme, the fenders are both white plastic items.

The forks featured on the front of this machine have been specially designed for trials use and are not of the multi-adjustable Hatta variety found on many of the dual-purpose Kaws. Anyone weighing more than 150 pounds will find that the fork springs are much too soft. Damping action is good, but the springs have got to go. Unfortunately, the inner diameter of the fork legs is small and it is difficult to find springs that will fit down inside the legs. We cured the problem somewhat by installing motocross springs out of the Ceriani C-4000 models that became popular Hodaka bolt-ons years back. The springs are slim enough to fit inside, and although they are progressively wound, and therefore not properly suited to trials work, where constant wind springs are preferred, they nevertheless worked better than what was stock. Especially with heavier riders aboard.

In back, a pair of softly sprung, fully chromed shocks handle damping chores. They do dampen well, but again, the spring rates could have been heftier. When at rest, the springs appear to be pretty well sacked. Sit on the machine and there’s almost no travel left back there. We set the five-position pre-load on the stiffest setting and eliminated the sacking appearance when at rest, but they could still be bottomed out under moderate use.

Unlike the forks, the wheels are not new to Kawasaki. Both hubs are KS125 enduro items. As on the KX125, which also uses them, the hubs come laced to super-strong D.I.D. rims. Naturally, the bike comes with Trials Universal (Dunlop) rubber. A 4.00-18 can be found at the rear, while a slim 2.75-21 makes steering precise.

If you look closely at some of the pictures, you can see that the backing plate on the conical front hubs has some unique features. First, the brake activating arm is bent sharply in the > middle in order to accommodate the cable and the manner in which its housing is braced. Second, there is a small tab with a hole in it that bolts up to the fork leg bottom to serve as the backing plate anchor. This is easy to accomplish because the front axle is mounted forward of the fork leg to reduce steering trail. On the other side of the hub is a speedo drive and a small speedometer mounted to the fork leg. This little gizmo serves little purpose in trialing. In fact, if it hadn’t been so intent on snagging on bushes as we competed on the KT, we probably wouldn’t even have noticed it.

Much in the same vein as the speedo are the headlight, taillight and oil injection system. The beam that the light throws out is very poor since it depends on rpm for juice, rather than battery-supplemented power. The horn should also be removed for competition, as should the gloppery of switches and buttons that serve only to confuse the person who is hanging onto the ill-adorned handlebars.

The oil injection is not so easy to discard. The unit itself isn’t heavy, even if you consider all the tubing and cables that are required for its proper functioning, so removal for the sake of weight is of little value. The real reason is to allow the cases to be brought in tighter against the engine and away from protruding rocks. But even if you are able to do so, the clutch housing, which is directly behind the injection-pump cover, sticks out just as far. And there’s virtually nothing that can be done to bring it in any tighter. Between the clutch bulge and the right footpeg hides the brake pedal. You’ll never bend this masterpiece of hide ‘n seek. Nice job.

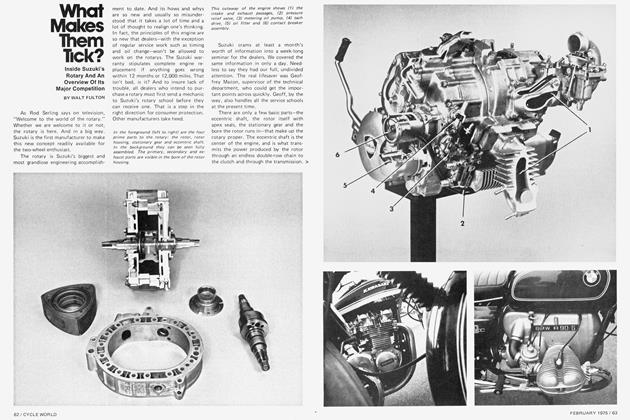

The KT250’s engine is another plus for Kawasaki engineers and former European Trials Champion, Don Smith, who was hired away from Montesa. At first the bike felt much like the Suzuki, i.e. too snappy. But that was only because we insisted on plonking around in first gear. Most sections will require second. The KT really shines in second gear. It can be lugged down very low, yet will still respond smoothly and strongly. First gear is only useful in the tightest nadgery, but controlling throttle settings in first is tricky.

Throttle response at any rpm is very predictable. The engine purrs, zips, slows, or screams, all depending on what the rider’s right wrist does. In this respect, the Kawasaki is clearly the best trialer to come out of Japan.

The power comes from a highly polished engine that has been specially tuned for smooth power. The motor is based, roughly, on the one used in the Fl 1, Kawasaki’s 250 enduro. Carburetion is by Mikuni and was well-benaved, with the exception of a few moments when the rings finally seated in and the engine suddenly began running rich. Dropping the needle one notch fixed that and things continued on troublefree. Those who ride in areas where extreme altitude changes are common will enjoy the carburetor, which allows you to change main jets without having to remove the float bowl.

Like all trials iron, the transmission ratios are in two categories. The first three gears are closely spaced for use in the observed sections, while the final two are arranged to assist high-speed travel between sections. The gear selector is mounted vertically on the KT, necessitating heel upshifts, but they weren’t any problem on this slick trans. What we would like to see on the bike would be some more serious footpegs. The stockers aren’t bad, but they could be better.

To smooth out power impulses, a chain tensioner is employed on the swinging arm. The unit is both well-designed—from the standpoint of functionalism—and sturdy. It operates pointing rearward, which keeps it from snagging on jagged rocks and being destroyed. As has become common practice on trialers since Montesa first used it on its earliest Cotas, the swinging arm section on the chain side doubles as an oil reservoir. A bleed valve at the rear can be adjusted to meter out lubricant a drop at a time, or it can just dump the entire contents of the reservoir on the chain in a matter of seconds for those who prefer instant rather than continuous lubrication.

Standing on the KT, you suddenly feel as though you’ve grown about a foot. The factors that contribute to this sensation are high footpeg placement, a low seat and rearset handlebar mounts on the upper fork crown. The only thing that can be done to cure the feeling is to rotate the bars forward so that an imaginary line between the two grips (which, by the way, are grim), runs directly through the center of the fork legs. This alleviates the cramped position, but introduces another problem. No matter how tight you snug the handlebars down, on very sharp drop-offs—especially as the wimpy forks bottom out—the handlebars will succumb to the pressure and rotate. We feel that the cramped riding position will detract from the Kaw’s appeal to larger riders and that, while designer Don Smith may like his handlebars set back in this manner, we would prefer having the bars mounted at a more customary point.

In spite of the bars, the Kaw was truly delightful. The wheelbase is slightly longer than those of the shortish Yamaha and Ossa mounts, but not quite as long as Montesas’ and Bultacos’. This allowed good control when lofting the front > end for obstacles, while yielding enough quickness for extremely tight turns. Which brings us to another gripe.

The KT steers very well to either side...until you get near full lock. Then the machine exhibits a trait whose cause we have been unable to diagnose. It wants to fall to the inward side of a turn. The front end begins to plow and starts to tip over to whatever side you’re turning toward. We experienced a mildly similar form of this sensation on the Kawasaki 175 enduro in our April ‘74 comparison test.

Also, the steering-head bearings have a tendency to tighten up as you ride. We loosened the pressure on the bearings and secured the pressure plate below the upper crown with its own lock nut, but it freed itself and tightened the bearings again. A rider may learn to correct for the falling-in tendency just as we did, but he may have to find a better way of securing the tension on the steering-head bearings, lest they get squished down and make quick maneuvering difficult.

Each trials machine on the market has its own share of peculiarities, both good and bad. Some we’ve found easier to ride than others. The Kawasaki was good, but not the easiest we’ve found. In fact, none of the Japanese bikes can yet compare to their pre-established competitors. They are getting closer, however. Among the Japanese trialers, the Yamaha steers slightly better than the Kaw. It also has better suspension in its stock form. So does the Suzuki. But the KT has the torquiest, most controllable engine yet, if you remember to keep it out of first gear unless you’re climbing trees. Brakes on all three are superb; and here Spain could take a lesson. The KT didn’t leak oil anywhere and didn’t get all grundgy. It returned from many an outing looking as though it had spent the whole time basking in the sun.

The Kawasaki KT250 is the best trialer out of Japan. But not by much. Given the KT’s power characteristics, the Yamaha would be the equal of Spanish machinery. Given the Yamaha’s steering precision, the same would be true of the KT. But no one Big Four manufacturer has gotten it all together yet. Unless Honda’s late arrival into the 250cc trials market is nothing short of sensational (rumor has it that it might be and CYCLE WORLD will have the first test), then Barcelona will continue to rule a sport that it has dominated since the late ‘60s.

KAWASAKI KT250