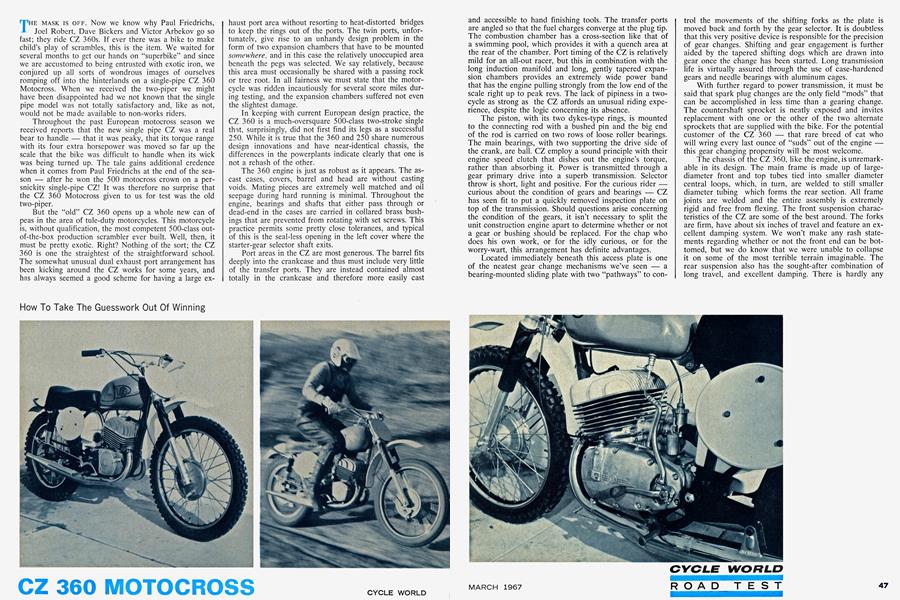

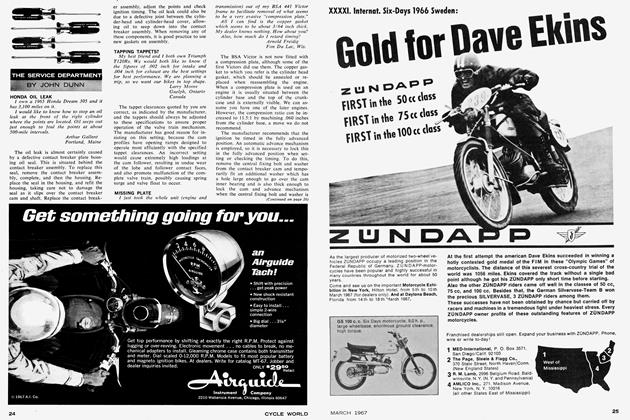

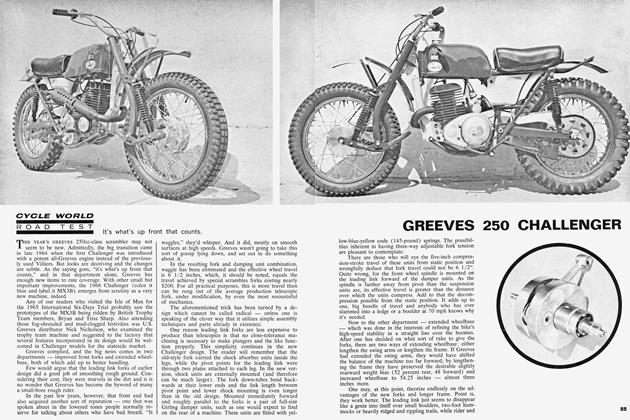

CZ 360 MOTOCROSS

THE MASK IS OFF. Now we know why Paul Friedrichs, Joel Robert, Dave Bickers and Victor Arbekov go so fast; they ride CZ 360s. If ever there was a bike to make child’s play of scrambles, this is the item. We waited for several months to get our hands on “superbike” and since we are accustomed to being entrusted with exotic iron, we conjured up all sorts of wondrous images of ourselves romping off into the hinterlands on a single-pipe CZ 360 Motocross. When we received the two-piper we might have been disappointed had we not known that the single pipe model was not totally satisfactory and, like as not, would not be made available to non-works riders.

Throughout the past European motocross season we received reports that the new single pipe CZ was a real bear to handle — that it was peaky, that its torque range with its four extra horsepower was moved so far up the scale that the bike was difficult to handle when its wick was being turned up. The tale gains additional credence when it comes from Paul Friedrichs at the end of the season — after he won the 500 motocross crown on a persnickity single-pipe CZ! It was therefore no surprise that the CZ 360 Motocross given to us for test was the old two-piper.

But the “old” CZ 360 opens up a whole new can of peas in the area of tule-duty motorcycles. This motorcycle is, without qualification, the most competent 500-class outof-the-box production scrambler ever built. Well, then, it must be pretty exotic. Right? Nothing of the sort; the CZ 360 is one the straightest of the straightforward school. The somewhat unusual dual exhaust port arrangement has been kicking around the CZ works for some years, and has always seemed a good scheme for having a large exhaust port area without resorting to heat-distorted bridges to keep the rings out of the ports. The twin ports, unfortunately, give rise to an unhandy design problem in the form of two expansion chambers that have to be mounted somewhere, and in this case the relatively unoccupied area beneath the pegs was selected. We say relatively, because this area must occasionally be shared with a passing rock or tree root. In all fairness we must state that the motorcycle was ridden incautiously for several score miles during testing, and the expansion chambers suffered not even the slightest damage.

In keeping with current European design practice, the CZ 360 is a much-oversquare 500-class two-stroke single that, surprisingly, did not first find its legs as a successful 250. While it is true that the 360 and 250 share numerous design innovations and have near-identical chassis, the differences in the powerplants indicate clearly that one is not a rehash of the other.

The 360 engine is just as robust as it appears. The ascast cases, covers, barrel and head are without casting voids. Mating pieces are extremely well matched and oil seepage during hard running is minimal. Throughout the engine, bearings and shafts that either pass through or dead-end in the cases are carried in collared brass bushings that are prevented from rotating with set screws. This practice permits some pretty close tolerances, and typical of this is the seal-less opening in the left cover where the starter-gear selector shaft exits.

Port areas in the CZ are most generous. The barrel fits deeply into the crankcase and thus must include very little of the transfer ports. They are instead contained almost totally in the crankcase and therefore more easily cast and accessible to hand finishing tools. The transfer ports are angled so that the fuel charges converge at the plug tip. The combustion chamber has a cross-section like that of a swimming pool, which provides it with a quench area at the rear of the chamber. Port timing of the CZ is relatively mild for an all-out racer, but this in combination with the long induction manifold and long, gently tapered expansion chambers provides an extremely wide power band that has the engine pulling strongly from the low end of the scale right up to peak revs. The lack of pipiness in a twocycle as strong as the CZ affords an unusual riding experience, despite the logic concerning its absence.

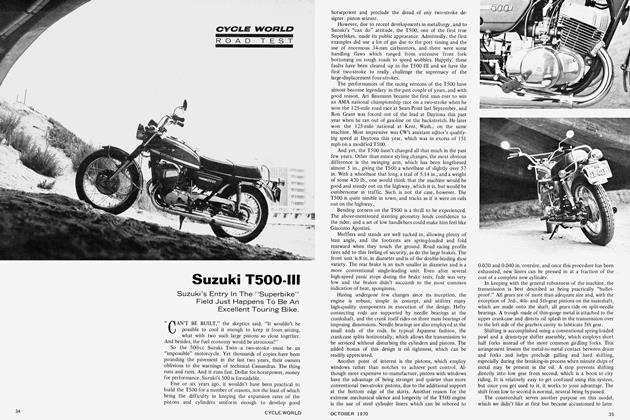

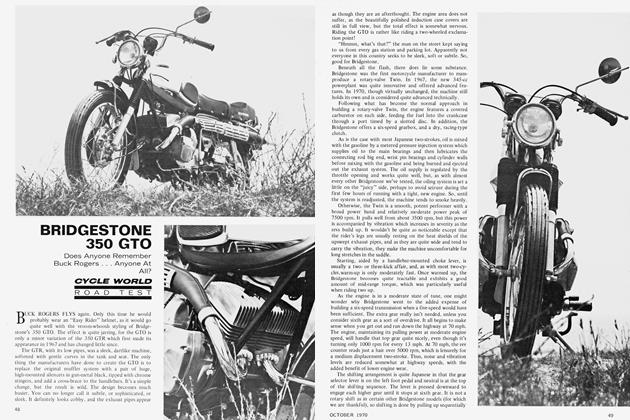

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The piston, with its two dykes-type rings, is mounted to the connecting rod with a bushed pin and the big end of the rod is carried on two rows of loose roller bearings. The main bearings, with two supporting the drive side of the crank, are ball. CZ employ a sound principle with their engine speed clutch that dishes out the engine’s torque, rather than absorbing it. Power is transmitted through a gear primary drive into a superb transmission. Selector throw is short, light and positive. For the curious rider — curious about the condition of gears and bearings — CZ has seen fit to put a quickly removed inspection plate on top of the transmission. Should questions arise concerning the condition of the gears, it isn’t necessary to split the unit construction engine apart to determine whether or not a gear or bushing should be replaced. For the chap who does his own work, or for the idly curious, or for the worry-wart, this arrangement has definite advantages.

Located immediately beneath this access plate is one of the neatest gear change mechanisms we’ve seen — a bearing-mounted sliding plate with two “pathways” to control the movements of the shifting forks as the plate is moved back and forth by the gear selector. It is doubtless that this very positive device is responsible for the precision of gear changes. Shifting and gear engagement is further aided by the tapered shifting dogs which are drawn into gear once the change has been started. Long transmission life is virtually assured through the use of case-hardened gears and needle bearings with aluminum cages.

With further regard to power transmission, it must be said that spark plug changes are the only field “mods” that can be accomplished in less time than a gearing change. The countershaft sprocket is neatly exposed and invites replacement with one or the other of the two alternate sprockets that are supplied with the bike. For the potential customer of the CZ 360 — that rare breed of cat who will wring every last ounce of “suds” out of the engine — this gear changing propensity will be most welcome.

The chassis of the CZ 360, like the engine, is unremarkable in its design. The main frame is made up of largediameter front and top tubes tied into smaller diameter central loops, which, in turn, are welded to still smaller diameter tubing which forms the rear section. All frame joints are welded and the entire assembly is extremely rigid and free from flexing. The front suspension characteristics of the CZ are some of the best around. The forks are firm, have about six inches of travel and feature an excellent damping system. We won’t make any rash statements regarding whether or not the front end can be bottomed, but we do know that we were unable to collapse it on some of the most terrible terrain imaginable. The rear suspension also has the sought-after combination of long travel, and excellent damping. There is hardly any question, however, that both suspension systems are greatly assisted in their chores by the unbelievably light magnesium-hubbed wheels. (The complete front assembly weighs 24 pounds.) The matter of unsprung weight is more serious an issue than most designers believe, but when the problem is given the concern it deserves and is solved in the way CZ have handled it, the benefits to the rider in terms of handling are immeasurable. It’s little wonder that wherever we took the bike and encountered other riders, covetous eyes were cast upon the 360’s wheels.

The final drive chain is an item that is rarely, if ever, discussed in a road test, other than a reference to its size, but in this case it is certainly something that merits attention. CZ manufacture their own chain, and what a chain it is! Between each pin and roller there is a brass bushing, and chain-life and lack of stretch resulting from this arrangement are incredible.

We noted with some interest that CZ have made some “body” changes in the new 360. Previously, fuel tanks and fenders were made of fiberglass, and the word “tank” applied to the gasoline reservoir was more than apt, because these components were uncommonly stout and heavy. Much of this has changed, however, for the fuel tank and front fender are now made of steel and, wonder of wonders, they’re lighter than the previous components. Also, these two items offer additional advantages in that the fuel tank has more capacity than the previous one, and the front fender springs back into shape like a Venetian blind slat. The rear fender is a two-piece affair with the front portion incorporating the still-air box and micronic filter. The vulnerable-looking rear fender peak is mounted securely inside the horizontal rear frame loop and is not so vulnerable, after all. Finish on these components, and the rest of the machine for that matter, is quite good for an all-out racer.

Thus far we have presented a detailed point-for-point set of impressions and observations concerning the CZ 360, and this is how it should be. But, when we approach that all important point — how does it perform — the “whys” and “wherefores” are quickly subordinated to the sensations of piloting this brilliant machine over impossibly rough terrain. To say that the engine has an incredibly broad power band is correct. To say that it is quicker than most 500-class machines on the top end is correct. To say that it is as tractable as a four-cycle single is correct. To say that it will outlast most of its competitors is correct. But, to say that its handling is excellent is an understatement. This is a motorcycle that is up to the abilities of the top runners just as it comes out of the box, and for the modestly experienced rider who takes his playing seriously, the CZ is also excellent.

One of the more curious things about this motorcycle is the universal suitability of its as-delivered condition. We refer here to its narrow section 21-inch front wheel and unprotected underside — points that bear little consideration in the eastern states, but are of major concern to western hare-and-hound riders. After wringing the bike out thoroughly, including a hot loop in a California harescrambles, we’re convinced that the CZ 360 needs virtually no mods for competition, regardless of which end of the continent you happen to ride upon. Weight bias is such that the skinny front tire does little more than function as a steering device when the power is being applied, and this same factor also keeps the motorcycle from crashing down hard on random immovable objects. All of this would seem to indicate that the machine has a penchant for wildly aviating its front wheel most of the time, but such is not the case; the CZ has a noticeably low c.g., and while it tiptoes through the tules, rarely will the front end rise more than à foot.

The total picture of the CZ 360 Motocross is capped off with the box of spares that are included with each bike — enough parts to carry the average rider through a full season. The bits include a complete piston assembly, bigend bearings, clutch pieces, a final drive chain, head and barrel gaskets, a set of cables, spokes, brake shoes, rear brake lever, footrests, gear selector lever, and many other little expendable items such as a condenser, spoke nipples and the like.

In all fairness to the CZ motocross riders, we admit that it takes a great deal more than an excellent machine to ride the championship trail, but we’d bet they would be the first to admit that the CZ 360 makes the ride a much easier one. ■

CZ 360cc

MOTOCROSS

$1295