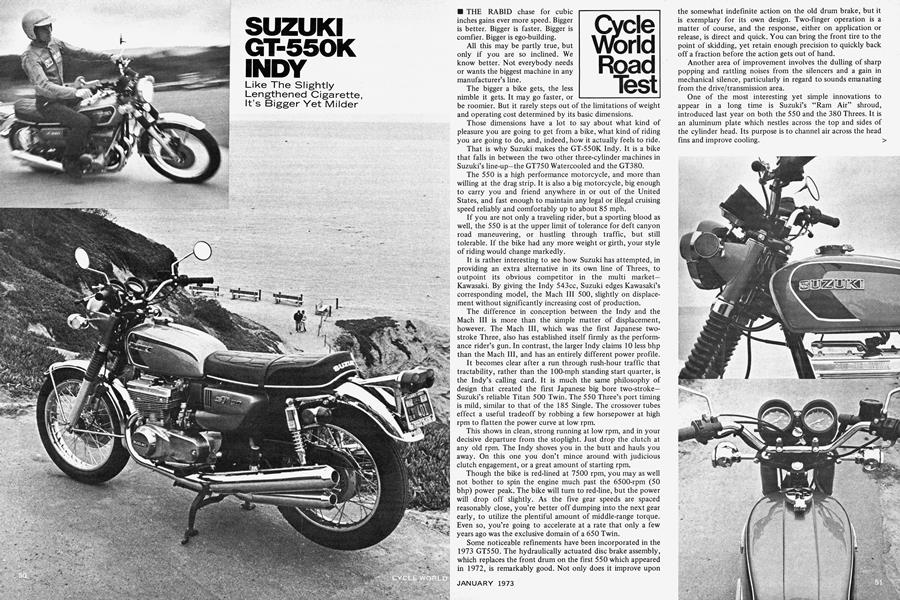

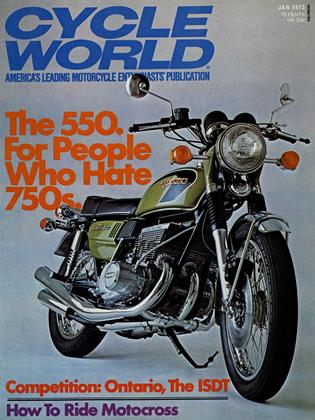

SUZUKI GT-550K INDY

Like The Slightly Lengthened Cigarette, It's Bigger Yet Milder

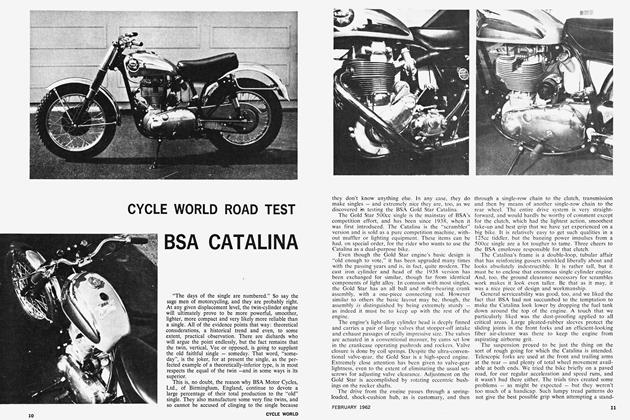

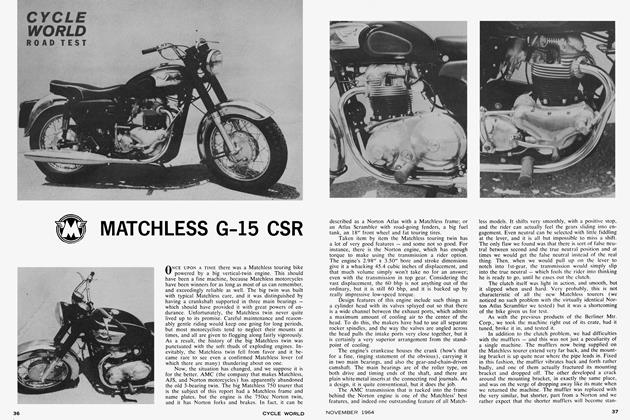

Cycle World Road Test

THE RABID chase for cubic inches gains ever more speed. Bigger is better. Bigger is faster. Bigger is comfier. Bigger is ego-building. All this may be partly true, but only if you are so inclined. We know better. Not everybody needs or wants the biggest machine in any manufacturer’s line.

The bigger a bike gets, the less nimble it gets. It may go faster, or

be roomier. But it rarely steps out of the limitations of weight and operating cost determined by its basic dimensions. Those dimensions have a lot to say about what kind of pleasure you are going to get from a bike, what kind of riding you are going to do, and, indeed, how it actually feels to ride. That is why Suzuki makes the GT-550K Indy. It is a bike that falls in between the two other three-cylinder machines in Suzuki’s line-up—the GT750 Watercooled and the GT380. The 550 is a high performance motorcycle, and more than willing at the drag strip. It is also a big motorcycle, big enough to carry you and friend anywhere in or out of the United States, and fast enough to maintain any legal or illegal cruising speed reliably and comfortably up to about 85 mph. If you are not only a traveling rider, but a sporting blood as well, the 550 is at the upper limit of tolerance for deft canyon road maneuvering, or hustling through traffic, but still tolerable. If the bike had any more weight or girth, your style of riding would change markedly. It is rather interesting to see how Suzuki has attempted, in providing an extra alternative in its own line of Threes, to outpoint its obvious competitor in the multi market— Kawasaki. By giving the Indy 543cc, Suzuki edges Kawasaki’s corresponding model, the Mach III 500, slightly on displacement without significantly increasing cost of production. The difference in conception between the Indy and the Mach III is more than the simple matter of displacement, however. The Mach III, which was the first Japanese twostroke Three, also has established itself firmly as the performance rider’s gun. In contrast, the larger Indy claims 10 less bhp than the Mach III, and has an entirely different power profile. It becomes clear after a run through rush-hour traffic that tractability, rather than the 100-mph standing start quarter, is the Indy’s calling card. It is much the same philosophy of design that created the first Japanese big bore two-stroke— Suzuki’s reliable Titan 500 Twin. The 550 Three’s port timing is mild, similar to that of the 185 Single. The crossover tubes effect a useful tradeoff by robbing a few horsepower at high rpm to flatten the power curve at low rpm. This shows in clean, strong running at low rpm, and in your decisive departure from the stoplight. Just drop the clutch at any old rpm. The Indy shoves you in the butt and hauls you away. On this one you don’t mince around with judicious clutch engagement, or a great amount of starting rpm. Though the bike is red-lined at 7500 rpm, you may as well not bother to spin the engine much past the 6500-rpm (50 bhp) power peak. The bike will turn to red-line, but the power will drop off slightly. As the five gear speeds are spaced reasonably close, you’re better off dumping into the next gear early, to utilize the plentiful amount of middle-range torque. Even so, you’re going to accelerate at a rate that only a few years ago was the exclusive domain of a 650 Twin. Some noticeable refinements have been incorporated in the 1973 GT550. The hydraulically actuated disc brake assembly, which replaces the front drum on the first 550 which appeared in 1972, is remarkably good. Not only does it improve upon

the somewhat indefinite action on the old drum brake, but it is exemplary for its own design. Two-finger operation is a matter of course, and the response, either on application or release, is direct and quick. You can bring the front tire to the point of skidding, yet retain enough precision to quickly back off a fraction before the action gets out of hand.

Another area of improvement involves the dulling of sharp popping and rattling noises from the silencers and a gain in mechanical silence, particularly in regard to sounds emanating from the drive/transmission area.

One of the most interesting yet simple innovations to appear in a long time is Suzuki’s “Ram Air” shroud, introduced last year on both the 550 and the 380 Threes. It is an aluminum plate which nestles across the top and sides of the cylinder head. Its purpose is to channel air across the head fins and improve cooling.

While it may seem to be reverse logic to cover something in order to improve cooling, it must be remembered that head and cylinder fins don’t cool by radiation, but by convection. The fins transfer their heat to the adjacent airstream, and warm the air. Incoming cool air replaces the warm air and is in turn heated and replaced.

But the airstream hitting the fins of a motorcycle is less than perfect. It is fouled by the front wheel, forks and frame tubes. It loses velocity, forms partial vacuums and slow eddy currents, such as those forming in a quiet pool alongside a raging river.

The purpose of the shroud is to focus the air blast, and to create a laminar—or airfoil—type of airflow on the fins. If you study the flow patterns created by a wing, you see that the

velocity of flow is straightest and fastest near the surface of the wing. In like manner, if you increase the velocity of the blast along the fins, and confine it to prevent it from swirling, and you thus increase the rate of replacement of warm air by cool air. Effectively cool the head and you reduce power loss at high, heavy-load speeds.

The Suzuki shroud is raised over the middle cylinder to provide extra air intake. Spark plug access is provided through holes in the shroud. An incidental benefit of the shroud is the damping of resonant noise from the engine, as well asa cleaning up of lines in the engine bay. From the side, the 550 could be mistaken for a four-stroke.

Indirect proof that a shroud is beneficial comes from racing. A tuner for a competing team borrowed the idea, and secured a 200 rpm increase in top gear at Laguna Seca. How more simple "and inexpensive can a 5 or 6 mph increase be!

Our main criticism of the 550 has to do with its ground clearance in turns and the stiffness of ride. Both these items arise from the art of engineering compromise: a big powerplant, multiple exhaust system, balance, need of comfort for rider and passenger, location of accessory items, fuel capacity and styling.

The bike is tall, yet for good handling the engine must ride low in the cradle. To meet the needs of power and of silencing, the mufflers must be low. The center stand must be accessible, and the result of the Suzuki solution is that it is lower than the cradle. Scrape! Long before you’ve approached the limit of turning traction, left or right, you hear the sound of metal grinding on pavement.

Springing stiffness also plays a part in this compromise. If the suspension were any more easy going than it is, the bike would bottom with little provocation. The tautness is actually pleasurable and secure feeling for the weekend play-racer, but would tax the endurance of a real long distance buff.

If the lack of ground clearance could be ignored, you would have what is essentially a beautifully balanced, stable handling machine. It’s one of those bikes on which you can release the handlebars at 80 mph and have it continue straight as an arrow, or respond accurately to middle body movement. Steering response is not heavy, considering the bike’s weight, but is slow; you don’t flip the bike into a tight corner, you guide it, and then settle solidly and surely on the selected line. Suspension damping action over rough roads offers predictable results, although the rear units are a bit shy of damping on the rebound.

The GT550 is replete with the conveniences which have become almost commonplace these days: electric starting, oil injection to obviate the need to mix oil with the gasoline, good electrical accessories, rationally organized controls and instruments, and even a convenient pinch-open gas cap latch that locks if you so desire. The horn button is easy to find with the thumb and you don’t have to look first. The brake and clutch levers are close enough to the handgrips so that you don’t have to have Simian hands to simultaneously operate the brake and throttle, or drape a wary finger over the clutch. Suzuki has also resisted the temptation to mount overly wide handlebars. A roadster is for the road, to be comfortable and yet knife through the wind, not to shovel the rider around like a half organic/half mechanical parachute.

To characterize the bike in few words, it is smooth, fast, manageable in most conditions and has all the earmarks of a reliable runner. It is not the traditional 500cc class machine as we have known it in the past. Its multi-cylinder performance and long-legged conception change that.

And its price makes it one of the best buys in the Suzuki line, second only perhaps to the 500cc Titan Twin. [§J

SUZUKI

GT-550K INDY

$1265