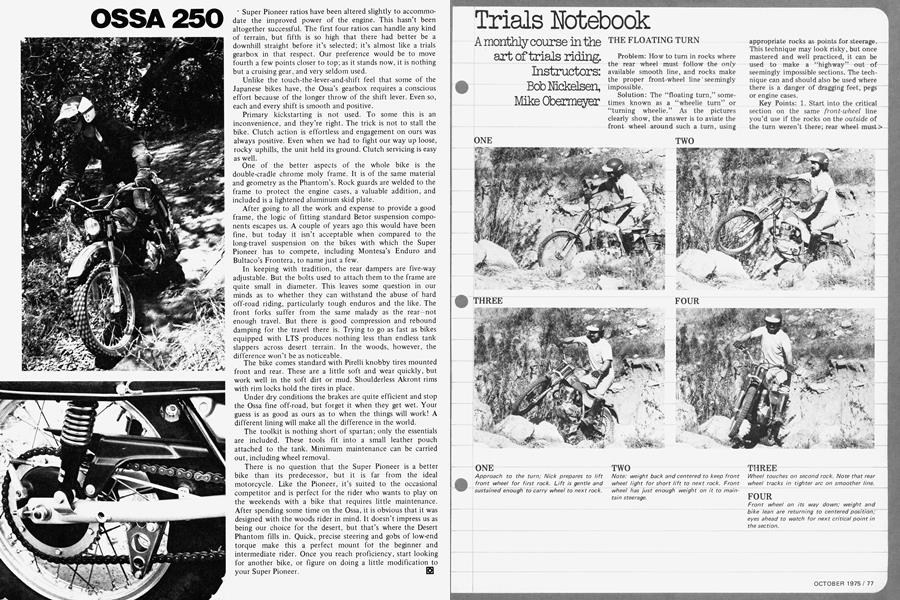

Trials Notebook

A monthly course in the art of trials riding. Instructors: Bob Nickelsen, Mike Obermeyer

THE FLOATING TURN

Problem: How to turn in rocks where the rear wheel must follow the only available smooth line, and rocks make the proper front-wheel line seemingly impossible.

Solution: The “floating turn,” sometimes known as a “wheelie turn” or “turning wheelie.” As the pictures clearly show, the answer is to aviate the front wheel around such a turn, using

appropriate rocks as points for steerage. This technique may look risky, but once mastered and well practiced, it can be used to make a “highway” out of seemingly impossible sections. The technique can and should also be used where there is a danger of dragging feet, pegs or engine cases.

Key Points: 1. Start into the critical section on the same front-wheel line you’d use if the rocks on the outside of the turn weren’t there; rear wheel must> track the appropriate line. 2. Initiate turn before you pick the front wheel up; bike should already be turning before you lift. 3. Smooth throttle with controlled lift; remember that you want the front wheel to graze the rocks for steerage as you make the turn. 4. Front end should merely be lightened, not picked way up. 5. Contrary to our usual recommendations, weight should be centered but may need to be slightly on inside peg, in order to keep hike turn ing. This is pretty much a matter for individual experimentation. Mick An drews once told us that he could initiate such a turn with weight on either peg, and could not offer a really comprehen sible answer as to why it worked both ways. Try it yourself and see, but, don `t put too much weight on the inside, or the bike will want to keep on turning when you want to straighten up. 6. The bike obviously must be leaned over into the turn; centrifugal force will make it want to plow out, and if the bike is leaned over properly, the turning force of the rear tire will oppose this centrifu gal force.

Alternate Method: Front wheel picked up high enough, and turn initi ated strongly enough, that front wheel comes around without any intermediate grazing. This can be made to work, but is dangerous, as is any move in which the front wheel is in the air for long periods of time with no steerage. You are totally committed, and if you didn't set it all up right, you may end up with a fiasco, as we say in Barcelona. As an intermediate approach, you may wish to hit some of the rocks In such a turn, especially if a few are significantly higher than the rest; the idea is to bring the front end around on a smooth line-not lift it up and down like a yo-yo.

RIDING DOWN A LOG

This is sort of a circus trick, not really appropriate for Continental-style trials riding. This technique is usable in some settings, however, especially where you must negotiate a ridge top, or "ironing board" rock. The klutzier half of your authorial pair was absolutely mystified by this procedure until Nick divulged the trick: The bike is not turned at all once on the log, and corrections are made by working the bike from side to side between your spread knees. Thé front wheel stays locked in a straight line. Voila: the front wheel doesn’t fall off, and neither do you!

BANKING OFF A LOG

A variant of our first technique, but useful in a circus trial, or in an erosioncarved creekbed where a ledge may allow you to find a much better rearwheel line. I’ve seen Mick Andrews do this with only the side lugs of his front tire hanging on a half-inch wide crack in a rock face.

SLANT LOG CROSSING

Applicable also to ledges. This is a guaranteed point-getter for most riders.

You already know how to go over a log, so we’ll just touch on the idiosyncracies.

Key Points: 1. Turn must be initiated before the lift, and must take you across at a fairly good angle. If you’re too close to parallel, you probably won’t make it. 2. Lift must be strong and high enough to clear the frame, or you’ll be knocked over when it hits on the inside. 3. Timing is much harder to judge—your unconscious “markers” have been shifted by the angle change. The drily answer is extensive practice, so that your mind will be able to integrate these changes into the new equation. 4. Throttle must be snapped off completely; if not, the rear wheel will slew sideways instantly. 5. Lastly, unweight as much as you can. The more weight there is on the rear wheel, the more likely the bike is to make a radical sideways slide. 6. Give yourself lots of room. Insidious trialsmasters often set club trial sections with a boundary at the end of such a log, so that a bad slide will throw your rear wheel off for a five. Avoid this by turning soon, as far from the dangerous end as possible.

We haven’t shown you anything you’ll see much of in the Scottish, or the Wagner Cup, but if you learn how to do all these well, and automatically, you’ll have added appreciably to your bag of tricks. Knowledge like this may not be a total substitute for trick reflexes, or ironman stamina, but it’ll take you a long way. 5]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

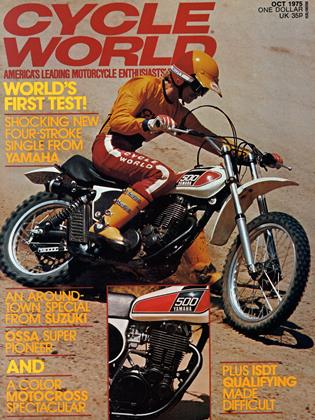

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

October 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

FeaturesSo You Want To Be An Isdt Rider?

October 1975 By D. Randy Riggs -

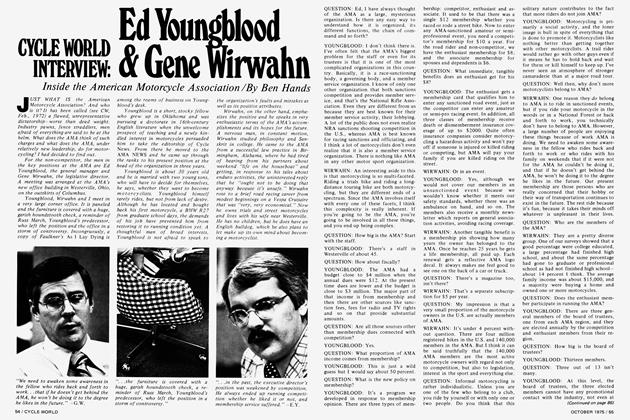

Cycle World Interview

Cycle World InterviewEd Youngblood & Gene Wirwahn

October 1975 By Ben Hands -

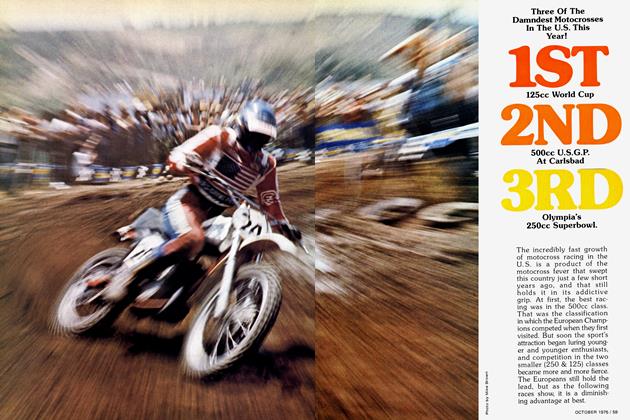

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureThree of the Damndest Motocrosses In the U.S. This Year!

October 1975