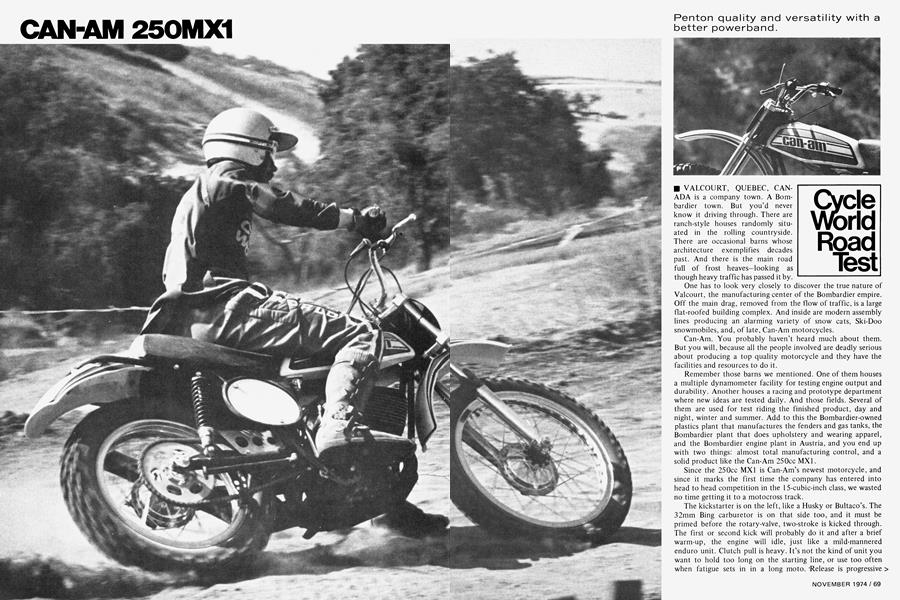

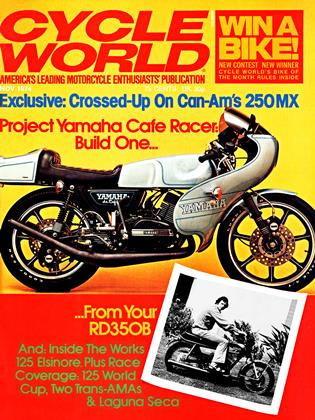

CAN-AM 250MX1

Cycle World Road Test

Penton quality and versatility with a better powerband.

VALCOURT, QUEBEC, CANADA is a company town. A Bombardier town. But you’d never know it driving through. There are ranch-style houses randomly situated in the rolling countryside.

There are occasional barns whose architecture exemplifies decades past. And there is the main road full of frost heaves—looking as though heavy traffic has passed it by.

One has to look very closely to discover the true nature of Valcourt, the manufacturing center of the Bombardier empire. Off the main drag, removed from the flow of traffic, is a large flat-roofed building complex. And inside are modern assembly lines producing an alarming variety of snow cats, Ski-Doo snowmobiles, and, of late, Can-Am motorcycles.

Can-Am. You probably haven’t heard much about them. But you will, because all the people involved are deadly serious about producing a top quality motorcycle and they have the facilities and resources to do it.

Remember those barns we mentioned. One of them houses a multiple dynamometer facility for testing engine output and durability. Another houses a racing and prototype department where new ideas are tested daily. And those fields. Several of them are used for test riding the finished product, day and night, winter and summer. Add to this the Bombardier-owned plastics plant that manufactures the fenders and gas tanks, the Bombardier plant that does upholstery and wearing apparel, and the Bombardier engine plant in Austria, and you end up with two things: almost total manufacturing control, and a solid product like the Can-Am 250cc MX1.

Since the 250cc MX1 is Can-Am’s newest motorcycle, and since it marks the first time the company has entered into head to head competition in the 15-cubic-inch class, we wasted no time getting it to a motocross track.

The kickstarter is on the left, like a Husky or Bultaco’s. The 32mm Bing carburetor is on that side too, and it must be primed before the rotary-valve, two-stroke is kicked through. The first or second kick will probably do it and after a brief warm-up, the engine will idle, just like a mild-mannered enduro unit. Clutch pull is heavy. It’s not the kind of unit you want to hold too long on the starting line, or use too often when fatigue sets in in a long moto. 'Release is progressive though, and the Can-Am will move off smartly, even at fairly low rpm.

At first the suspension felt stiff and we had reservations about the 82-lb. springs fitted to the S&W rear shocks. But as the day wore on, the ride became less and less harsh. It’s interesting to note here that even while the suspension was loosening up, the Can-Am had absolutely no tendency to pogo from side to side. When the rear wheel did bounce, the bike came straight up and remained in an attitude in which control was easy.

During break-in, we stayed on the seat a lot and, after a time, the foam padding settled to a pronounced degree. A slightly softer, but more resilient type of foam would be considerably better. Dimensions of the seat (width and thickness), however, are good.

So much for slow laps. We pulled up to a long, uphill starting line and did a burn out. Low gear produced too much

Éheelspin so we went back and tried second. With the revs maximum, we let the clutch out and the Can-Am came out hard. The bike didn’t come out perfectly straight, but you could leave the power on and that’s just what you want to do.

: Gear spacing would be ideal if it weren’t for the gap between third and fourth. The motor will pull it if the starting line area is flat or downhill. But on an uphill, a slight leveling off of acceleration occurs, even if the third-to-fourth shift was undertaken at maximum rpm.

Into a turn brake feel is good, but if the track is loamy and traction is optimal, units with slightly more stopping power wouldn’t hurt. This is especially true if that turn is a hairpin and the straight is a fifth-gear flyer.

On the Can-Am (if the steering head angle is set at 30 degrees), it’s best to dive under the opposition. The bike will hold a very tight line and it will steer where you point it. You can get on the gas a lot sooner than with some two-strokes, as well, because the powerband is broad and the transition onto the pipe isn’t too severe.

If you choose the outside line, it is better to square the turn

• The bike will slide in the lower gears, but at speed, the s tend to let go, both front and rear, simultaneously. This wash-out isn’t bad enough to cause à spill, but it costs time.

The problem here isn’t really one of geometry or weight distribution. It’s tires. The Can-Am comes with Yokohama rubber and, while these are far from the worst tires on the market, there are some better. On the Can-Am we would prefer either Metzeler or Trelleborg tires in the same 3.00-21 and 4.00-18 sizes.

On straightaways, wind the rotary-valve Single out...all the way out. There is good power in the mid-range, but the maximum is still put out on the top end. And, unlike the 175, which has performance on everything in its class, the 250 does not. Mind you, it’s not slower than anybody else’s stock 250, but it’s no faster either. The advantage, as we indicated before, is in the powerband and smooth transition of power that lets you get on the gas harder, sooner.

Through bumps or whoop-de-doos, the Can-Am tracks straight. It’s best to sit back a bit because the front end isn’t overly light, but beware of getting slapped in the rear by the

*. Rear suspension travel just isn’t all that much, and even ugh damping and spring rate are good, the units can be bottomed. It’s not as good a set-up as say the Yamaha YZM’s monoshock.

Can-Am is aware of the problem and they are experimenting with several different rear suspension configurations, but none has proven durable enough to suit them. So, until they get something to last, their rear suspension will remain average.

Up front, Betor forks with 6.5 in. of travel do a better job, just as has always been the case with traditionally-suspended motorcycles. They are capable of taking considerably rougher terrain in stride than the rear units and, unlike some Betors we’ve tested, these did not leak one drop of oil.

About the only other handling situation a person is likely to encounter on a motorcross course is a fast sweeper. If the sweeper is smooth, and if the machine is traveling fairly straight during the transition of acceleration to braking, everything is fine. But, if the turn is bumpy, and if you have to make the transition from acceleration to braking when the bike is sliding, the front end wiggles. It doesn’t tank slap and throw you off, it just wiggles enough to make you cautious.

In spite of the wiggle, we felt the geometry to be a good compromise between steering precision and stability. But on the Can-Am, if the geometry doesn’t really suit you, you can alter it easily and inexpensively. All you have to do is change cones in the steering head, or in some cases, rotate them 180 degrees front to rear. They will key in place in either location. Any fork angle from 25 to 31 degrees in 0.50-degree increments is possible. Stock is 30 degrees (see diagram A).

The Can-Am will hold its own on a motocross track, but motocross isn’t the only thing the bike does well. For one thing, it’s an excellent cow trailer. The low pipe is protected by a bash plate, the noise level is surprisingly low for a competition machine, and it’s got the right kind of power for either hillclimbing or fireroading.

FORK ANGLE~~ ADJUSTMENT

The standard fork angle on your Can.Am is 30 degrees and provides the optimum steering and handling for most types of riding~ However the fork angle is adjustable from 25 degrees to 31 degrees inclusive to provide fork angles that may be more suitable for specific racing or competition applicatson&

The following table gives a list of cones to be used to attain a given fbrk angfe~

CAN-AM

250MX1

$1395

Bolt on lights and you’ve got yourself one super enduro mount. If you don’t like to piece together street legal equipment on your own, go to a Can-Am dealer. “T‘nt”

(Can-Ams dual-purpose line) parts will fit. And the bike is sturdy enough to go the distance...any distance.

The engine is very similar to the 175cc unit...and that one is virtually impossible to break. The same aluminum alloy engine castings are used, but machining is different to allow for la^r crankshaft wheels and a different bore and stroke, wfe crankshaft rides on ball bearing main bearings and the heftier connecting rod features needle bearings top and bottom. The piston is cast and sports two rings.

*Tfle Can~Am r coideat 11w ht~h~st b p reading olany 2S0 MX to dare

There are four generous transfer ports, and one exhaust port in the cylinder barrel. Both the head and barrel are finished in black, with polished cooling fin edges. The rubber blocks fitted to the enduro versions for noise control have been left out.

What is unusual about the Can-Am engine, and what gives it the smooth powerband, is the rotary valve stuffed into the left c^^case half. On most rotary-valve two-strokes the carburetor is mounted inside the engine cases and that makes engine width excessive. But not on the Can-Am. Their engineers mounted the carburetor externally, narrowed the engine cases, and connected the carburetor and valve with a tuned aluminum housing. It’s more complicated than a piston-port design, and it is slightly heavier, but the reliability and power make up for the additional complexity.

Also on the left side of the engine are straight-cut primary gears driving a wet, multi-disc clutch. The transmission on both the 125s and 175s is a six-speed, but on the 250 only five ratios are used. The idea behind this move is added strength. By taking out the sixth cog, they could make the remaining five wider and that’s exactly what was done.

Behind the right case is a Bosch capacitor discharge ignition system, consisting of a magneto, an electronic control unit, and an emergency stop switch. Also on the right is the Mikuni oil injection pump. Oil for the injection system is stored in the top tube of the frame and there is a dip stick to check the oil le^^just forward of the gas tank.

^!ide from the large top tube reservoir, frame design is conventional double cradle with strengthening members just aft of the engine. Mild steel is used instead of chrome moly, but the weight penalty is not too severe. Total frame weight is just two pounds more than a Honda Elsinore unit.

Hubs are conical, but they are not light. Some magnesium alloy here and for the engine cases would really be beneficial. Unusual are the rubber plugs at the hub/spoke junction that keep the spokes in place in the event of breakage. Rims are Akront, which is to say they are strong but will collect mud and debris. We prefer a shoulderless design like that DID offers.

Controls are generally well thought out. The shift lever is wide and doesn’t gouge the top of your boot. The rear brake pedal, unlike those on previous Can-Ams, is adjustable in height. The older models had the pedal mounted too high for easy use. Handlebars are of moderate height and width and will suit most riders. Magura power levers are nice, but the grips are too hard and cause blisters instantly. Also, a quicker-responding throttle and a lighter carburetor return spring are in order.

The fuel tank, fenders, and air box are plyable plastic and are virtually unbreakable. The striping decals, however, deteriorate quickly. In fact, in a few months, they look downright scruffy and detract greatly from the appearance of the machine.

Bombardier spends a lot of time perfecting their machines and it shows. The Can-Am 250cc MX1 is fast, but durable. It can be raced hard weekend after weekend with only minimal maintenance.

But there are a couple of problems. That extra strength means some extra weight. And Bombardier’s preoccupation with total reliability has kept them out of the suspension travel race...at least for the time being. |§

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycles, Rehabilitation And A Funky Jamboree

November 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

November 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

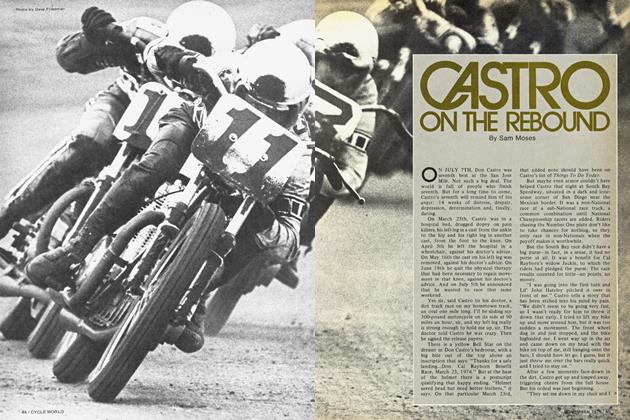

FeaturesCastro On the Rebound

November 1974 By Sam Moses -

Competition

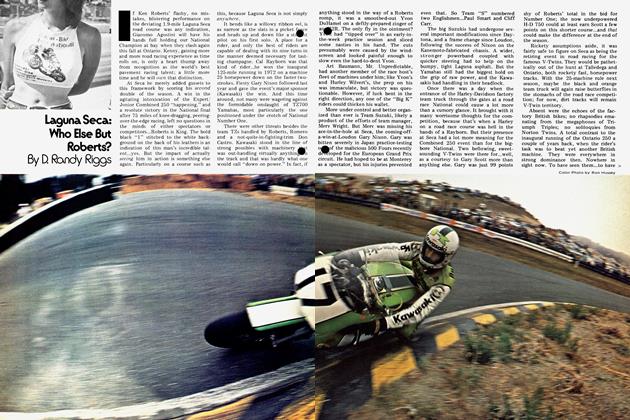

CompetitionLaguna Seca: Who Else But Roberts?

November 1974 By D. Randy Riggs