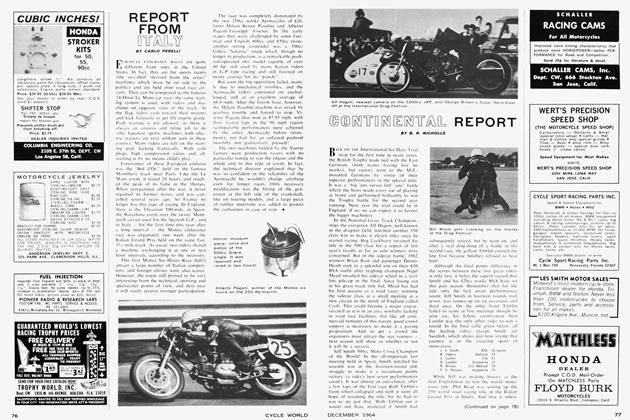

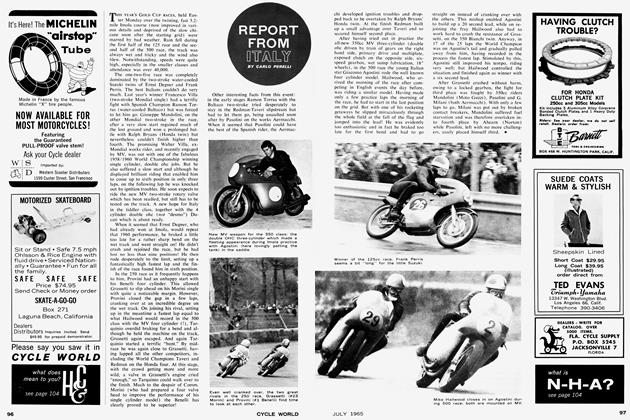

REPORT FROM ITALY

DE TOMASO DEVELOPMENTS

CARLO PERELLI

Alejandro de Tomaso has left Ford completely or Ford has compelled the dynamic Italo-Argentine to do so. As a matter of fact, the “Automobili de Tomaso” from Modena and the “Ghia” and “Vignale” car body factories from Turin, already 80 percent Ford owned, have now passed completely to the American firm’s control.

Alejandro has founded, in Modena, the “De Tomaso SpA” for the production of the luxurious 2+2 “Longchamp” car, but he stated that from now on his greatest effort will be made in motorcycles. He owns 57 percent of the American “Rowan” and this firm owns 67.5 percent of Benelli and 99.9 percent of Moto Guzzi—the two biggest Italian factories.

Under vigorous pushing from de Tomaso, Benelli has quickly renovated its wide production and Moto Guzzi is going to be made more active. Technical co-operation between the two factories is also in the works. For example, the famous Moto Guzzi technician Lino Tonti has been requested to design a super frame for the Benelli 750 Six.

“However,” says de Tomaso, “each factory will have its own full range of models, even having competition between them, to improve the breed and organization of each factory.” But this is not going to be applied to the sports field because Benelli is scheduled to compete in GPs while Moto Guzzi is taking part in production racing the 750s.

MV 50% GOVERNMENT OWNED

Another shock in the Italian indus try: MV is now 50 percent Government owned. For once this is not due to economical problems but to the fact that the Italian Government has formed a big group for helicopter production and MV has been practically compelled to enter it at 50/50 conditions.

There’s no worry about motorcycle racing, however. Count Corrado Agusta again signed Giacomo Agostini, Phil Read and Alberto Pagani. They are going to contest the GP series at home and abroad as usual plus some 750 Formula races, but not Daytona since the chain version is not ready for the big USA event.

Main attention has been directed toward the GP field. To prevent the |‘strokers” threat, mainly from Yamaha, The 350 Four has been beefed up to 70 bhp and fitted with a new frame, designed with the computer’s aid. Moreover, the 500 Four has been readied, on the same lines as the 350, and bench testing of the power unit has shown a 90 bhp output (compared to the 83 for last year’s three-cylinder model); weight and dimensions have been described as “favorable.” There is, however, one break from tradition: under Ago’s (and Read’s) well publicized protests, MV is not going to contest the TT for the first time since 1952.

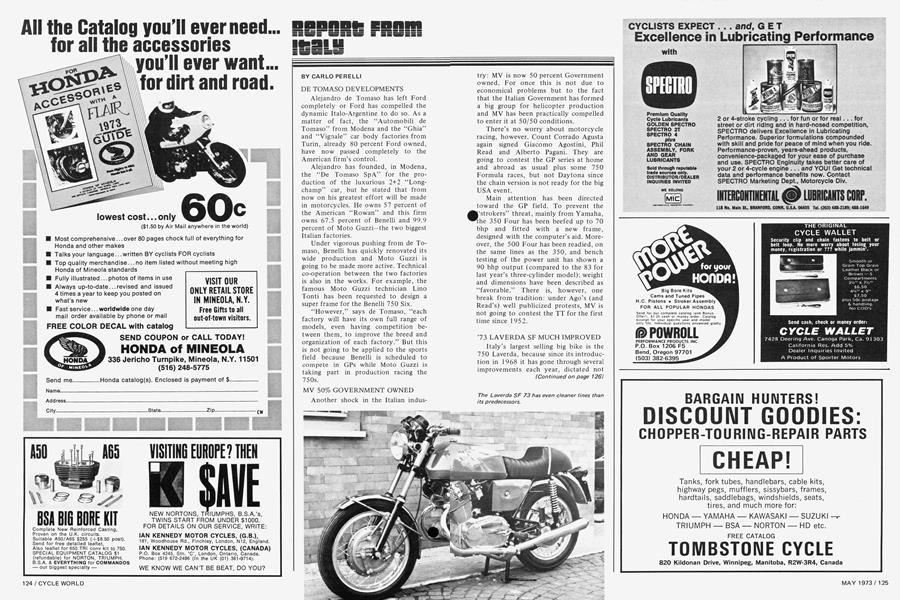

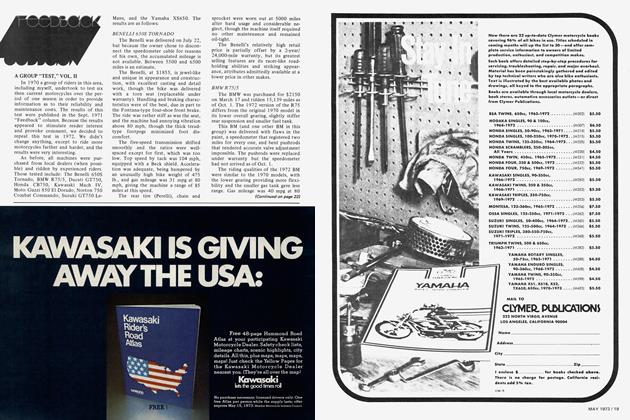

’73 LAVERDA SF MUCH IMPROVED

Italy’s largest selling big bike is the 750 Laverda, because since its introduction in 1968 it has gone through several improvements each year, dictated not only by racing experience but also by user suggestions and complaints.

(continued on page 126)

Continued from page 125

The biggest improvement, however, was made in the 1973 version, mainly to improve “ridability” and low-medium rpm performances.

The well-proven frame of the racing version has been used, with metallic bushes at the rear swinging arm spindle (instead of plastic) and a lower placed, lighter battery. Moreover, the same racing suspension (by Ceriani) is now fitted.

To make the engine more flexible, breathing has been increased, c.r. lowered and valve timing made milder. Valves are now much bigger (41.5mm inlet, 35.5mm exhaust, previously 38 and 34) and so are the carburetors, still Dellorto but of 36mm diameter instead of 30mm and featuring the so-called acceleration pumps, manually actuated on opening the throttle control. CR has been taken down from 9.9:1 to 8.9:1, enabling the use of normal plugs (more dependable and long lasting) as well as lower lead gas. The results have been beneficial in the top end section also; in fact, power has stepped up from 60 to 66 bhp at 7200 rpm (with a capability of being revved to 7600 rpm without harm) and so the fantastic limit of 124 mph now is at hand. Pick-up now starts from as low as 2000 rpm and the time over the standing quarter, measured by an independent source, was 13.272 sec.

So the Laverda, now more pleasant to ride on twisty courses or in town traffic, still requires a certain effort at high speeds, especially in taking it up straight after a very fast bend, but surely less than in last year’s version. Anyway, the bike sticks to its line without wobbling—it weighs 465 lb. in running condition.

Braking has also been improved, by fitting the competition units developed and patented by Laverda, with the shoes well protected in a finned case inside the drum. These stoppers, called Super Freni (super brakes) give the name SF to the bike.

The fine sohc, five-speed, with electric starter from Northern Italy is more silent, also. In fact, a 78mm diameter connector tube positioned just ahead of the rear wheel directs the gases coming from the right exhaust pipe to the left silencer and vice-versa. This is said to improve extraction. The silencers are finely shaped and rubber mounted.

Gasoline consumption has remained practically unchanged and the price to the public in Italy is slightly less than $2000.

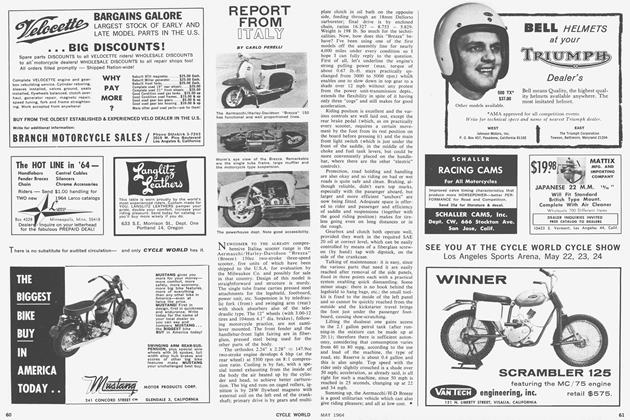

MOST LOVED OF ALL

The most coveted Italian vintage mount is undoubtedly the Moto Guzzi 500 “Sport 14,” built from 1922 to 1930 with only slight modifications in 11,000 units, a remarkable figure for those times, when export was practically unknown to the Italian industry and the inner market was far from being receptive.

Why is the “Sport 14” so sought after by the Italian collectors? Because it made history in motorcycle technique, because of its unorthodox yet functional lines, because it’s still fascinating to look at, to hear and to ride, because it is a Moto Guzzi and because it’s the most classic of them all.

The Moto Guzzi 500 prototype was conceived during the first world war by plane pilot Carlo Guzzi, it was built in 1919 (and is still to be admired in the Mandello del Lario factory museum),

but proved to be too complex and expensive to build.

It featured a horizontal cylinder oversquare engine (with the crankcase enclosing the primary drive, the clutch, the gearbox and the drive to the magneto), it had full automatic lubrication, with feed and scavenge pumps, sohc by bevel shaft, four valves and double ignition. The external flywheel was already there as was the double cradle frame. Power was 17 bhp, exceptional for those times, and top speed was 80 mph, another fantastic figure.

The production version, coming from the small Mandello del Lario workshop in 1921 and called “500 Normale,” retained many valid features of the prototype but had side inlet valve and pushrod operated overhead exhaust valve, single ignition and of course was less powerful and slower. Figures were, in fact, 12 bhp at about 3800 rpm and 56 mph. But it was also simpler and sturdier and therefore more lasting and reliable, requiring practically no maintenance, the great virtue of all veteran Moto Guzzis. The tubular frame included some pressed steel elements at the rear end. For 1922 these were scrapped in favor of an all tube layout and the “Sport 14” was born.

Among the advantageous features were the 88x82mm bore and stroke dimensions for less piston speed and better breathing, the horizontal cylinder for better cooling, the engine running "backward," not only to eliminate an intermediate gear between the crank shaft gear and the clutch drum to get the rotation "right" again but, more important (as evidenced in the works catalogs of the time), to have the crankshaft itself throwing oil toward the upper part of the cylinder, otherwise difficult to lubricate. The feature of the inlet side valve and the overhead exhaust valve was a compromise. It was evident since then that the ohv represented the better system but in those times the valves had a bad habit of breaking often. If they were in the head, they would fall into the cylinder. So Carlo Guzzi put the less fatigued inlet valve at the side and the exhaust one (which needed better cooling) in the head, so to have a more rational combustion chamber shape. (The feature of the opposed valves was not infrequent in those times, but it used to be reversed, i.e. side exhaust and overhead inlet).

(continued on page 128)

Continued from page 127

Also, the oil tank, under the steering column, was well cooled and the double pump, a rarity for those times, provided efficient circulation. The “Sport 14” had a very low architecture, a weight of only 242 lb. and gave an impression of compactness and sturdiness. It had a very low center of gravity and was easy to ride because of the extreme flexibility of the engine, with a compression ratio of only 4:1, and not vibrating at all, thanks to the big external flywheel.

The “Sport 14” has incredible idling and pulling power. Once one has mastered the use of the valve lifter and the spark advance, plus the levers for the air and the throttle, the engine comes easily to life and has an incredibly low rhythm.

I took part in an “old irons” race on the famous Monza autodrome aboard a perfectly maintained “Sport 14.” The controls require a special adaptation period. The rear brake pedal, for example, is heel actuated. And even the gear lever that required a long time to operate compelled the rider to take his right hand off the handlebar, making the bike swerve ever so slightly! The engagement of the three cogs is by no means silent, even if carefully performed, and acceleration is slower than that of a modern “50.” And don’t speak about braking...until 1926 the “Sport 14” had no front brake.

A few laps at full throttle proved the strength of the power plant which, at the end, again idled at an incredibly low speed. The only snag was some overflow from the scavenge pump, which made oil leak from the tank.

But of course the “Sport 14” must not be treated with the hurried mentality of our times. To enjoy it most it must be taken along twisty country lanes and over hills; then pottered around quietly. It is still possible tö taste the subtle flavor enjoyed by our fathers.