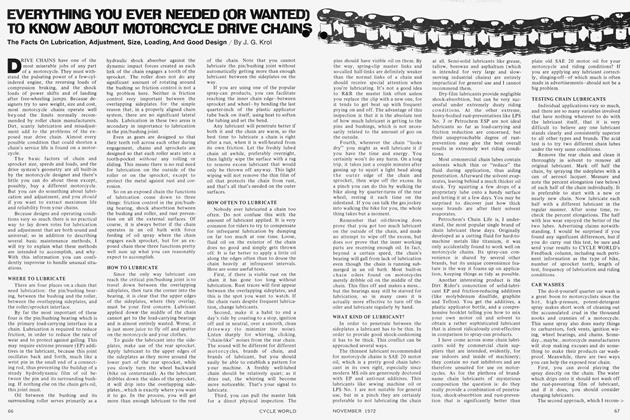

No-Fault Insurance—| Both Pro and Con

Here's The Facts, Minus Assorted Trivia Used By Hard-Sell Tacticians

J. G. Krol

YOU'VE HEARD a lot about No-Fault Insurance recently-mostly glowing claims about how it will solve all the problems of vehicle insurance, but also some grumbled warnings that it could prove disasterous for motorcyclists. Most of what you’ve seen has consisted of specific examples, dramatic details, and other assorted trivia that makes very effective propaganda to advance a point of view, but that provides no basic background information so that you can form your own viewpoint on the matter. This report attempts to answer some of the questions you need to consider to put the problem in perspective.

Question: What does insurance do from the viewpoint of the individual?

Answer: It substitutes a certain,

small, frequent outlay of funds for an uncertain, large, infrequent outlay of funds. Thus it reduces risk, smooths out your cash flow, and adjusts to the time-value of money. This service costs money, just like buying on credit costs money. Over a 50-year driving career the average driver must have paid more in premiums than he received in benefits, the difference being the cost of providing the services of risk reduction and so on.

Q: What does the insurance system do as a whole?

A: It determines the amount and distribution of transferred funds and, of course, carries out the mechanics of the transfers. The flow diagram gives an idea of how funds are distributed out of the insurance system. The input distribution is determined by the rates charged various highway users and the laws forcing or prohibiting them from buying insurance. Insurance systems differ in the way they determine the amount and distribution of transferred funds.

Q: Why is the amount of transferred funds important to consider?

A: First, it is the basic measure of the size of the insurance system. Second, it concentrates attention on what advocates of particular proposals often try to sweep under the rug: that the system neither creates nor destroys money; every dollar that flows into the system must come out somewhere and every dollar that comes out must have gone in somehow. Third, it avoids the

emotional bias of more value-laden terms.

Q: What emotional bias is that?

A: The insurance industry has always been very clever in using terms that sound good or bad, and the same is true of insurance reformers. A “good” term like “benefits” automatically implies that the quantity ought to be increased, but a “bad” term like “losses” creates the impression that the quantity ought to be reduced. “Beneficiaries” sounds worthy and deserving, while “claimants” sounds greedy and self-serving. “No-Fault concept” sounds reasonable and progressive, but “evasion of personal responsibility” sounds immoral and socially destructive. Insurance “benefits” should be maximized, but insurance “costs” should be minimized. “Senseless killing on the highways” is terrible, yet “creation of job opportunities” is highly desirable. In each case, a propagandist has his choice of terms, one implying we need more of the thing, the other implying we need less. The literature on No-Fault Insurance (NFI)—both for and against—supperates with such value-laden terminology. Highway “safety” and highway “carnage” are two names for the same situation, the exact same set of facts. Have you ever heard anybody say that we need more carnage and less safety? Conversely, when someone insists we need less carnage and more safety he is saying nothing at all, for those policy recommendations are built into the words themselves.

Q: What about the distribution of transferred funds?

A: If an insurance proposal does not change the amount of funds transferred, the only thing it can do is alter their distribution. If Smith is to pay less, Jones must pay more. If Smith is to gain bigger benefits, Jones must wind up with smaller benefits. If more dollars are to be paid in small claims, fewer dollars must be paid in large claims. Advocates of insurance schemes do much thinking and talking about who will gain, but little thinking and talking about who will lose, should their ideas be adopted. In some cases, particularly motorcyclists, insurance reformers never even think about the effects of their proposed redistribution of costs and benefits.

Q: How will NFI affect the amount of funds transferred by the insurance system?

A: Astonishingly, there is no clear answer to this basic and obvious question. NFI proponents stress the promised reduction in insurance rates for some highway users for some kinds of insurance, which seems to imply a reduction in the total amount of transferred funds, but other rates may go up. Furthermore, many NFI plans contemplate forcing more people to buy more insurance, by law, and some plans, like that of Daniel P. Moynihan, would bring new funds into the system by taking money away from highway building and by adding an extra “penny or so” to the gasoline tax. Based on the track records of politicians, major industries, and the public, it is hard to believe that new laws will decrease the flow of funds through the insurance system.

Q: How will NFI affect the distribution of insurance costs?

A: Under a pure Liability System of insurance, your costs would tend toward the amount of damage you did to other people, as evaluated by a court of law or equity. Your premiums would be proportional to: Probability of (your being in an accident) x Probability of (your causing the accident, as determined by a court) x Average value of (other party’s damages, as determined by a court).

The existing system is a combination of first-party insurance (fire, theft, collision, medical, etc.) and liability insurance. Even the part that is called “liability” is not a pure Liability System. In practice, your premiums are determined by: Premiums for first-party insurance + Probability of (your being in an accident) x Average value of (total damages, as determined by a court).

Under a typical NFI plan your premiums would depend on: Probability of (your being in an accident) x Average value of (fixed, predetermined awards + your out-of-pocket expenses, as determined by bureaucratic procedure).

Under a pure No-Fault System— which is not what is being proposed by anybody under the name NFI—your premiums would tend toward: Probability of (your being in an accident) x Average value of (your losses, as determined by a court). This is the same as for existing first-party insurance, whether on your car, your house, your recreational vehicles, your valuable art treasures, or whatever.

There is a rough consistency in direction in the way costs would be distributed moving from pure Liability System to the existing system to NFI to pure No-Fault System, so it is convenient to use the two “pure” systems—neither of which exists or is being proposed—to establish the directions of cost shifts. The amounts of these shifts depend, of course, on the specifics of each individual plan, but the directions can safely be identified.

NFI tends to decrease costs for people who are more likely than average to have caused a collision in which they are involved; it tends to increase costs for people who are less likely than average to have caused a collision in which they are involved.

NFI tends to decrease costs for people who cause more damage than they sustain; it tends to increase costs for people who suffer more damage than they inflict.

NFI tends to decrease costs for people who do not stand to lose very much by being in a collision; it tends to increase costs for people who stand to lose much by being in a collision.

Q: How do these tendencies apply to motorcyclists?

A: First, when a motorcycle collides with another vehicle, that other vehicle is almost always a car. Available statistics suggest that the driver, based on elementary criteria of right-of-way, was responsible for causing the collision about twice as often as the rider. There are cogent reasons to believe that if the data err, they understate the discrepancy in causation, which may be as high as 3:1 against the driver (lack of a doctrine of presumptive responsibility on the driver, as operates between drivers and pedestrians; latent hostility towards motorcycles; the driver’s subconscious knowledge that he is physically invulnerable if he hits a bike; the rider’s conscious and subconscious awareness that he is highly vulnerable if he hits a car; the convenience and ready acceptability of the “I didn’t see him” excuse). Since drivers as a class of highway users cause disproportionately many of the car-bike collisions, and riders as a class of highway users cause disproportionately few, NFI will tend to shift insurance costs from drivers to riders.

Furthermore, since most of the things drivers hit are not bikes but most of the things riders -are hit by are cars, the cost reduction per driver will be much smaller than the cost increase per rider. To put it another way, suppose NFI shifts a certain total amount of cost from drivers to riders. Since there are more than ten times as many drivers as riders, the reduction in premiums per driver will be less than one-tenth as much as the increase in premiums per rider.

Second, regardless of who caused a collision, the car is likely to do far more severe injury to the motorcyclist than the bike is likely to do to the driver. NFI will tend to make each pay for his own injuries, indicating a shift of cost from drivers to riders. The same effect holds between big cars and small cars, and between trucks and cars. In each case, the class of highway user who is likely to come out the worse will pay the bigger premium.

Third, regardless of the relative proportioning of injuries in a given car-bike collision, it is generally true that a rider is likely to sustain more extensive injuries in any collision between vehicles than the driver of a modern Armored Personnel Carrier (though the situation may be just the opposite for single vehicle crashes, which are especially lethal to automobilists). NFI will tend to increase costs for motorcyclists again. The same effect works between the driver of a sports car, who is likely to be the vehicle’s only occupant, and the head of a large family, who may often have half-a-dozen wives, children and relatives riding with him in his station wagon. Whatever increases your potential losses increases your insurance premiums, regardless of whether you’ve ever been in a collision, let alone caused one. This effect is probably more important in shifting costs among drivers than in shifting costs between drivers and motorcyclists.

In short, under the ancient concept of liability (as modified by the more modern doctrine of negligence) drivers are liable for most of the bodily injury in most car-bike collisions, and this is reflected in their insurance costs. Under NFI the costs would be shifted from the tortfeasors (the drivers) and onto their victims (the motorcyclists); because of the disparity in numbers, this implies a negligible rate reduction for drivers and a significant, order-of-magnitude larger increase for motorcyclists. >

Q: How could anybody seriously

propose so outrageously unfair a system of insurance?

A: That itself is an unfair question. The fundamental assumption on which NFI is based is that liability is more-orless equally distributed over all highway users or, at least, over most of them. If this is true, it is certainly reasonable to propose replacing individual justice in each collision with a sort of average justice over all collisions, for as the proponents of NFI point out—and as they sometimes exaggerate—determining liability is a service that costs money, just as all the other aspects of claim adjusting cost money, and if we can get along as well without this service as with it, the ratio of premiums paid to benefits received can be somewhat decreased for the insurance system as a whole.

NFI proponents have their eyes on the similarities among most of the drivers of the most numerous class of vehicles, private cars; within this large, homogeneous group the basic assumption that everybody’s liability is very close to the average is tolerably accurate, and the essential precondition for at least considering NFI does exist. The difficulties arise when you consider all the other identifiable groups of highway users whose liability and losses are not necessarily close to the average set by most drivers of most cars. By no means are motorcyclists the only group of highway users that present difficulties to the NFI concept.

Q: So motorcyclists are not the only group that will suffer from NFI?

A: True, but one-sided. Every group of highway users that differs significantly from the “average” driver of the “average” car will either gain or lose; not everybody will gain, not everybody will lose. Each group of highway users must be examined in detail and compared to the “average” driver of an “average” car to determine how it will fare under NFI.

Some groups of highway users that have been considered, or are worth considering: drunk drivers, trucks, pedestrians, government-owned vehicles, drugged drivers, reckless drivers, bicyclists, taxicabs, public buses, charter buses, farm implements, unlicensed military vehicles maneuvering on the highways (e.g., tanks), heavy tractor-trailer rigs, rent-a-cars, stolen vehicles, suicidal drivers, unlicensed drivers, construction equipment, utility workers and street repair crews who are working on, in or under the roadway, company cars, chauffeured cars, foreign vehicles and drivers, emergency vehicles, houses being moved, drivers and vehicles operating under diplomatic immunity, pushcarts and...motorcyclists.

Perhaps the most striking group of highway users that NFI must contend with are those who intend—even maliciously intend—to cause a collision. This group is especially instructive because (a) it illustrates why no NFI proposal ever advanced truly and completely abandons the liability concept, and (b) it shows that the mere numerical size of a group of highway users is not necessarily the full measure of its significance.

Q: What do practical NFI plans do about such groups?

A: It’s obvious that the more groups of highway users you consider, the more complicated your NFI scheme becomes. Thus, the first reaction of NFI proponents is to minimize, and if possible to ignore, the existence of such diverse groups. If somebody makes a big enough stink that a given group cannot be ignored, NFI proponents often respond by making special provisions in their plans to restore equity between this group and the “average” driver of an “average” car.

For example, the Hart Plan refuses to pay benefits when the driver is in the process of committing a felony, when he is driving a stolen car, or when he “intends” to cause harm. Other NFI schemes make exemptions for drunk, drugged and suicidal drivers. Recognizing that a car-pedestrian collision will cause far more injury to the person afoot than to the driver of the car—a relation that holds almost as strongly between motorcyclists and drivers— most NFI plans place the full cost of coverage on the driver, saying in effect that the driver is always liable when he hits a pedestrian.

Q: If that reasoning is valid for cars versus pedestrians, isn’t it equally valid for cars versus motorcyclists?

A: That is an excellent question to ask the proponents of NFI, whether at the federal level or in your own state. Since motorcyclists have not yet kicked up enough of a fuss so that they cannot continue to be ignored, advocates of NFI are still ignoring them.

Q: So a fair distribution of costs between drivers and riders is possible under NFI?

A: Certainly, because “NFI” is an extremely broad and vague term. See the accompanying examples of how NFI plans can differ to the extent of being completely contradictory.

Q: How about the distribution of benefits under NFI, compared to the present system?

A: NFI proponents love to chatter on about the myriad details of the benefits to be paid under their various schemes, which vary enormously: one plan pays “reasonable” funeral expenses, another makes a flat payment of $1000, a third pays different amounts depending on the age of the decedent, and so on and so on, until you really start worrying about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. The essence of NFI is not to be found in long lists of details, but in the general procedures and objectives of benefit distribution, the main ones being these:

(1) Take the determination of benefits out of the hands of courts and lawyers and place it into the hands of clerks and bureaucrats.

(2) Eliminate or reduce the number of awards for intangibles, chiefly, “pain and suffering.”

(3) Eliminate all, or at least reduce the number of, very large awards.

(4) Narrow as much as possible the range of variation in awards to different people suffering the same injury (e.g., a concert pianist should get no more than anybody else for the loss of one of his fingers).

(5) Eliminate lump sum settlements; pay benefits in dribs-and-drabs to meet provable out-of-pocket expenses as they actually arise.

(6) Make sure that nobody ever comes away from a traffic accident with disposable personal income (i.e., cash in hand that he, and not anybody else, can do with as he chooses).

(7) Take the determination of the amount of the benefit out of the hands of the claimant as much as possible.

Proponents of NFI are very eager to point out the shortcomings of benefit distribution which will be eliminated under their plans, and do so at great length: greedy, 'incompetent, ambu-

lance-chasing lawyers; extreme delays in overcrowed courts; unpredictable, erratic, whimsical jury decisions; the uncertainty and high cost of litigation; great variations among awards for similar injuries; the ability of clever, informed claimants to gain bigger awards than foolish, ignorant claimants. All of these things are consequences of a “legalistic” procedure of benefit determination.

But proponents of NFI become tight-lipped and vague when discussing the drawbacks of benefit distribution under their own plans: a multiplication of forms and paperwork; endless lines leading to barred windows manned by faceless bureaucrats; proliferation of mysterious, complex procedures unknown to anyone but the apparatchiks who administer them; powerful tendencies to force all cases to fit the same rigid patterns, whether or not this seems fair or reasonable; narrowing of personal freedom of choice and room for maneuver at every step of the process; an increase in the sense of frustration, helplessness and alienation that most people experience in dealing with a bureaucracy...or in being forced to deal with it. All of these things are consequences of a “bureaucratic” procedure of benefit determination.

NFI tends to replace legalistic procedures with bureaucratic procedures in its distribution of benefits.

That one sentence says all there is to say on the subject; yet, amidst all the vast literature on NFI, right here is probably the first time it has ever been stated so plainly. Reformers joyously condemn the existing system for being legalistic, and defenders of the status quo will point out the bureaucratic implications of NFI, but neither side is anxious to use both terms together, each in its proper place, for both of them are “bad” terms—“legalistic” and “bureaucratic” both have downright rotten connotations.

Q: How will the more bureaucratic procedures of NFI affect motorcyclists?

A: Very little. That is, motorcyclists will be treated much the same as everybody else, however well or poorly that may be.

If a form of NFI including coverage of vehicle damage is enacted—some proposals include this, others don’t—the reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses will work to the disadvantage of motorcyclists, many of whom are more interested in and more able to carry out their own repairs and modifications than owners of cars. When a car damages your bike, the size of the payment you receive is based on the shop-cost of repairing the machine to its prior condition, but once you receive this payment, you can do with it whatever you want; it is disposable personal income. Instead of having a stock fender replaced in a shop, you might buy a custom fender and install it yourself; or you might pick up a cheap used fender and spend the money for a fancy custom paint job; or you might decide to run without the fender and to put all the money into a custom-laced wheel, or into the engine, or into those special tools you’ve been wanting, or whatever. Under NFI, the only choice will be to have the machine repaired to a deadstock condition in a factory-authorized repair facility. Predictably, this will overload the repair shops even more than they are today, driving repair prices yet higher; and this will eventually show up in increased insurance costs. Under NFI the more mechanically inclined motorcyclists will find themselves paying more and getting less.

Q: Is there any way that motorcyclists will benefit from NFI?.

A: First, an important factor in the recent rash of repressive measures directed against motorcyclists has been the natural loathing of insurance companies to pay liability settlements, especially to a class of highway users who are not among its own policyholders. Hence, pressures on government to compel motorcyclists to take extraordinary measures, not so much to protect themselves as to minimize the liability losses of automotive insurance carriers. (If “lights-on” works for bikes and Greyhound buses, why not for cars? If abrasion-resistant clothing for motorcyclists, why not fire-resistant clothing for automobilists?) By reducing the liability of drivers, thus of their insurors, NFI reduces the economic motivation to force motorcyclists to “protect” themselves. Who dares call this irony?

Second, it is impossible to generalize further because NFI plans differ so greatly among themselves. Conceivably, a form of NFI which fairly distributed responsibility over highway users in proportion to the inherent injurycausing capability of their vehicles to other highway users would benefit motorcyclists not merely via reduced insurance premiums but, more importantly, by instilling in the drivers of two-ton steel juggernauts the same caution toward motorcyclists they now exercise toward pedestrians, bicyclists, kids on skateboards, and traffic cops somehow surviving smack in the middle of congested intersections. But this will surely not come about if motorcyclists fail to demand equitable treatment from their elected representatives.

Q: Why is NFI being proposed, anyway?

A: Like any great public issue, the discussion over NFI proceeds on two > different levels at once: conscious, explicit, logical-sounding arguments, or “derivations,” and unconscious motivations, or “sentiments.”

Q: What are the conscious argu-

ments?

A: First, determining fault is largely wasted effort under modern highway conditions. Second, by eliminating fault-determination, more of each premium dollar could go to benefits. Third, by this elimination, benefits could be paid more quickly and surely. Fourth, the inequities of very large and very small payments would be eliminated.

Q: What is the evidence for these claims?

A: First, the more statistical evidence is collected about the relative liability of various classes of highway users, the less tenable becomes the assumption that everybody causes and suffers about the same amount of injury. As for the “modern conditions” theme, it need merely be noted that somebody or other has been proposing NFI almost continually for over half a century.

Second, the latest information from Massachusetts, after a year of experience with NFI, is that the promised reduction in insurance costs has somehow managed to become a fairly general increase in insurance premiums. The few other test cases are either ingermane, or have not been in operation long enough to reach any conclusions.

Third, only a fraction of 1 percent of claims under the existing system actually enter the lengthy court process; it is hard to see how NFI could speed payment in the great majority of cases. Even under NFI, a few cases will result in lengthy litigation, e.g., to determine whether or not a driver had “intent” to cause injury...a concept at least as difficult to resolve as negligance.

The fourth claim is immune to evidence.

Q: What are the sentiments behind proposals of NFI?

A: First, widespread dissatisfaction with the way the present insurance system works combined with the vague hope that any change will be for the better. Second, the belief that people are not, or ought not to be, directly and dramatically responsible for the consequences of their actions. Third, a preference for equality over diversity. Fourth, presumption in favor of government intervention. Fifth, miscellaneous personal motivations (politicians riding a popular issue to higher namerecognition, academics imposing their theories on the real world, insurance executives defusing customer resentment, etc.). >

What Does NFI Really Mean?

The Keeton-O’Connell Plan, the prototype of current NFI proposals, specifically exempted coverage of property damage. The plan introduced in the 1968 Rhode Island legislature was described as being based on the K-O proposal; it included coverage of property damage up to $5000.

The Preferred Risk Mutual Insurance Company of Des Moines, Iowa, offered what it called a No-Fault Plan in 1969. This plan did absolutely nothing to change the existing system of tort liability.

Senator Philip A. Hart (D., Mich.) insisted in his No-Fault Plan that NFI must be enacted on a national basis. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners insisted in its proposals that NFI must be enacted by individual states and adapted to local conditions.

The “Social Protection” NFI plan adopted by Puerto Rico in 1968 “territorialized” the insurance industry by creating a government monopoly in highway user insurance. The NFI plan of the Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company of Columbus, Ohio, jealously preserved the interests of private insurance companies.

South Dakota passed a law compelling insurance carriers to offer certain optional coverages along with their basic automobile insurance packages. According to U.S. News & World Report (1971 July 26), this was “No-Fault Insurance. ”

The NFI plan of Professor Leon Green would provide no compensation for “pain and suffering. ” The NFI plan of the British Columbia Royal Commission would provide no limit on the compensation for pain and suffering.

The NFI plan of Professors Clarence Morris and James C.N. Paul of the University of Pennsylvania would reduce awards by the amount of collateral source benefits (i.e., other forms of insurance, like Blue Cross). The NFI plan of Frank R. Miley, Director of the Chicago Board of Underwriters, would not deduct collateral source benefits.

Some NFI plans would require the operators of commercial vehicle fleets to participate. Other NFI plans would prohibit them from participating.

Saskatchewan has a legally enacted, compulsory form of NFI. All the rest of Canada has an informal, non-legally enacted form of NFI operating among the insurance companies themselves, and based on the “knock-for-knock” system used in Great Britain for over half a century.

Almost all NFI plans are coercive, with the government telling drivers, riders, insurance companies, and everybody else involved precisely what they must and must not do. Nonetheless, the NFI plan of Drake University Law School Professors M.G. Woodroof III and Alphonse M. Squillante is deliberately and explicitly voluntary.

Some NFI plans totally prohibit recovery of damages under tort liability proceedings. Other plans permit such recovery beyond certain “cut-off levels.” NFI plans that do have cut-off levels pick numbers that vary by as much as an order of magnitude.

Obviously, NFI could either include or exclude motorcycles and still be called “No-Fault Insurance. ”

Where Did NFI Come From?

1898 First automobile bodily injury liability insurance policy is sold to give liability protection to owners of horsedrawn vehicles.

1919 Rollins and Carman suggest, in two unrelated articles, that the then-new concepts of Workmen’s Compensation be applied to automobile accident compensation.

1920s Judge Robert Marx of Cincinnati offers detailed NFI proposal for automobile accidents.

1932 Columbia University Report by the Commission to Study Compensation for Automobile Accidents recommends NFI.

1944 Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, a socialistic political party made UP of farm and labor leaders, wins election victory in Saskatchewan and moves to implement its concept, based partly on above 1932 U.S. report, for “average justice” for all motorists instead of “absolute justice” in each case.

1946 Saskatchewan Plan is enacted and becomes first formal NFI plan of automobile insurance on the continent.

1950s Professor Albert E. Ehrenzweig, Professor Leon Green, and Professor Fleming James advance various NFI proposals.

1953 California Legislature rejects Collins Plan, which was based on Columbia study and derived from Workmen ’s Compensation.

1965 Robert E. Keeton and Jeffrey O’Connell begin a serious, sustained, and highly effective effort to popularize NFI. They write books and articles, give lectures, draft a “model statute” ready for adoption by any state legislature, etc.

1960s Growing public debate over smog, traffic congestion, highway safety, safety of individual vehicles, etc.

1967 Insurance industry scoffs at NFI, predicts early death for concept. K-0 Plan defeated in Massachusetts Senate.

1968 Puerto Rico adopts NFI “Social Protection” Plan, first U.S. jurisdiction to do so. Many polls are taken to gauge public sentiment in the contiguous 48. Insurance industry sits up and takes note of groundswell of customer dissatisfaction and begins to advance its own counterproposals for NFI. Scores of NFI proposals surface in law journals, insurance journals, government publications, and popular press. The phrase “No-Fault Insurance” becomes fixed in the public consciousness.

1970 Massachusetts becomes first state to adopt NFI. An important feature is the promise, enacted as part of the law, that insurance premiums will be slashed 15 percent across the board. Bill is signed into law on August 13. On November 18, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court nullifies provision of law cutting insurance rates.

1971 Florida adopts the “Florida Automobile Reparations Reform Act,” a form of NFI. Delaware adopts NFI law. Illinois adopts NFI law. Massachusetts NFI goes into effect at beginning of year. Senator Philip A. Hart proposes national NFI as result of previous hearings at which Robert E. Keeton was a star witness.

1972 Massachusetts announces that, based on experience with NFI, insurance premiums will, in general, go up for the coming year. NFI is defeated in California and in the U.S. Congress. NFI advocates lay plans for intense effort in 1973 legislative sessions. Nixon Administration adopts policy of favoring state-by-state experimentation with NFI until enough data are in to see how it works.

1973 Motorcyclists do I do not (pick one) make their needs heard by their federal and state representatives and are as a result ripped off(treated fairly (pick one) by the same.

Q: What can be said about these sentiments?

A: Nothing. Tastes, preferences and value judgments aren’t amenable to rational discussion; they just are, like gravity or mortality.

Q: What can motorcyclists do to secure fair treatment under NFI?

A: Their most important task is to make their existence known to their representatives in state and federal governments. Presently, the Nixon Administration and most State governments are working for a state by state approach to NFI, while some Congressmen want a nationwide form of NFI enacted at the Federal level. NFI proposals tend to start very simple and to become more and more complicated the longer and more thoroughly they are debated. Legislators are not going to go out of their way to accommodate a group of highway users which fails to make its needs known through letters, telegrams, phone calls, etc.

Q: How can NFI be adjusted to the needs of motorcyclists?

A: Both by the extent of injury done and by the disproportion in responsibility, motorcyclists are the victims of automobile drivers. Most people find it morally outrageous that a class of highway users which is systematically victimized should be forced to pay for its own losses, while the class of tortfeasors which causes those injuries should pay nothing. NFI is primarily designed for the average driver of the average car, and motorcyclists simply don’t fit those averages...no more than do pedestrians, house-movers, or horse-drawn carriages which are still common in certain regions of the country. Whatever the value of the no-fault concept among drivers— or for that matter, among motorcyclists—it does not make sense between drivers and riders when the latter are predominantly the victims of the former. Motorcycles should be exempted from a system of NFI designed to cover automobiles.

Q: Where can more information on NFI be obtained?

A: Most of the articles and books on NFI are blatant propaganda. Avoid anything whose title contains words like “New,” “Crisis,” “Carnage,” and so on.

The best single source of information on NFI is the book No-Fault Insurance by Dr. Willis Park Rokes of the University of Nebraska. This book is specifically designed to summarize everything said, known, or done about NFI up to October 1971, both for and against. The failure of motorcyclists to make themselves heard is poignantly illustrated by the fact that even Dr. Rokes, amidst 416 detail-packed pages of information, does not have a single mention of the severe hardship that this class of highway users would suffer under a rigid, doctrinaire form of NFI. |51