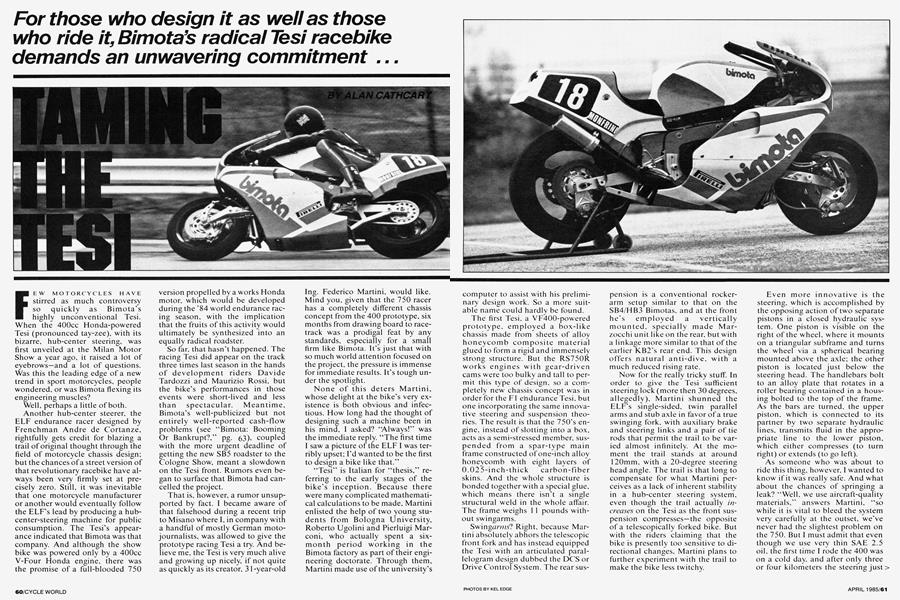

TAMING THE TESI

For those who design it as well as those who ride it, Bimota’s radical Tesi racebike demands an unwavering commitment ...

ALAN CATHCART

FEW MOTORCYCLES HAVE stirred as much controversy so quickly as Bimota’s highly unconventional Tesi. When the 400cc Honda-powered Tesi (pronounced tay-zee), with its bizarre, hub-center steering, was first unveiled at the Milan Motor Show a year ago, it raised a lot of eyebrows—and a lot of questions. Was this the leading edge of a new trend in sport motorcycles, people wondered, or was Bimota flexing its engineering muscles?

Well, perhaps a little of both. Another hub-center steerer, the ELF endurance racer designed by Frenchman Andre de Cortanze, rightfully gets credit for blazing a trail of original thought through the field of motorcycle chassis design; but the chances of a street version of that revolutionary racebike have always been very firmly set at precisely zero. Still, it was inevitable that one motorcycle manufacturer or another would eventually follow the ELF’s lead by producing a hubcenter-steering machine for public consumption. The Tesi’s appearance indicated that Bimota was that company. And although the show bike was powered only by a 400cc V-Four Honda engine, there was the promise of a full-blooded 750 version propelled by a works Honda motor, which would be developed during the ’84 world endurance racing season, with the implication that the fruits of this activity would ultimately be synthesized into an equally radical roadster.

So far, that hasn’t happened. The racing Tesi did appear on the track three times last season in the hands of development riders Davide Tardozzi and Maurizio Rossi, but the bike’s performances in those events were short-lived and less than spectacular. Meantime, Bimota’s well-publicized but not entirely well-reported cash-flow problems (see “Bimota; Booming Or Bankrupt?,” pg. 63), coupled with the more urgent deadline of getting the new SB5 roadster to the Cologne Show, meant a slowdown on the Tesi front. Rumors even began to surface that Bimota had cancelled the project.

That is, however, a rumor unsupported by fact. I became aware of that falsehood during a recent trip to Misano where I, in company with a handful of mostly German motojournalists, was allowed to give the prototype racing Tesi a try. And believe me, the Tesi is very much alive and growing up nicely, if not quite as quickly as its creator, 31-year-old Ing. Federico Martini, would like. Mind you, given that the 750 racer has a completely different chassis concept from the 400 prototype, six months from drawing board to racetrack was a prodigal feat by any standards, especially for a small firm like Bimota. It’s just that with so much world attention focused on the project, the pressure is immense for immediate results. It’s tough under the spotlight.

None of this deters Martini, whose delight at the bike’s very existence is both obvious and infectious. How long had the thought of designing such a machine been in his mind, I asked? “Always!” was the immediate reply. “The first time I saw a picture of the ELF I was terribly upset; I’d wanted to be the first to design a bike like that.”

“Tesi” is Italian for “thesis,” referring to the early stages of the bike’s inception. Because there were many complicated mathematical calculations to be made, Martini enlisted the help of two young students from Bologna University, Roberto Ugolini and Pierluigi Marconi, who actually spent a sixmonth period working in the Bimota factory as part of their engineering doctorate. Through them, Martini made use of the university’s computer to assist with his preliminary design work. So a more suitable name could hardly be found.

The first Tesi, a VF400-powered prototype, employed a box-like chassis made from sheets of alloy honeycomb composite material glued to form a rigid and immensely strong structure. But the RS750R works engines with gear-driven cams were too bulky and tall to permit this type of design, so a completely new chassis concept was in order for the F1 endurance Tesi, but one incorporating the same innovative steering and suspension theories. The result is that the 750’s engine, instead of slotting into a box, acts as a semi-stressed member, suspended from a spar-type main frame constructed of one-inch alloy honeycomb with eight layers of 0.025-inch-thick carbon-fiber skins. And the whole structure is bonded together with a special glue, which means there isn’t a single structural weld in the whole affair. The frame weighs 1 1 pounds without swingarms.

Swingarms? Right, because Martini absolutely abhors the telescopic front fork and has instead equipped the Tesi with an articulated parallelogram design dubbed the DCS or Drive Control System. The rear suspension is a conventional rockerarm setup similar to that on the SB4/HB3 Bimotas, and at the front he's employed a vertically mounted, specially made Marzocchi unit like on the rear, but with a linkage more similar to that of the earlier KB2’s rear end. This design offers natural anti-dive, with a much reduced rising rate.

Now for the really tricky stuff. In order to give the Tesi sufficient steering lock (more then 30 degrees, allegedly), Martini shunned the ELF’s single-sided, twin parallel arms and stub axle in favor of a true swinging fork, with auxiliary brake and steering links and a pair of tie rods that permit the trail to be varied almost infinitely. At the moment the trail stands at around 120mm, with a 20-degree steering head angle. The trail is that long to compensate for what Martini perceives as a lack of inherent stability in a hub-center steering system, even though the trail actually increases on the Tesi as the front suspension compresses—the opposite of a telescopically forked bike. But with the riders claiming that the bike is presently too sensitive to directional changes, Martini plans to further experiment with the trail to make the bike less twitchy.

Even more innovative is the steering, which is accomplished by the opposing action of two separate pistons in a closed hydraulic system. One piston is visible on the right of the wheel, where it mounts on a triangular subframe and turns the wheel via a spherical bearing mounted above the axle; the other piston is located just below the steering head. The handlebars bolt to an alloy plate that rotates in a roller bearing contained in a housing bolted to the top of the frame. As the bars are turned, the upper piston, which is connected to its partner by two separate hydraulic lines, transmits fluid in the appropriate line to the lower piston, which either compresses (to turn right) or extends (to go left).

As someone who was about to ride this thing, however, I wanted to know if it was really safe. And what about the chances of springing a leak? “Well, we use aircraft-quality materials,” answers Martini, “so while it is vital to bleed the system very carefully at the outset, we’ve never had the slightest problem on the 750. But I must admit that even though we use very thin SAE 2.5 oil. the first time I rode the 400 was on a cold day, and after only three or four kilometers the steering just packed up—locked solid. It transpired that in low ambient temperatures, the piston controlling the wheel gets too cold, the hydraulic fluid decreases in volume, and the pressure swiftly drops to zero in only two or three minutes. When this happens, you can’t steer the bike. So to compensate, we fitted a diaphragm next to the fluid reservoir under the seat. And when the pressure drops because of low temperature, the diaphragm automatically pressurizes the hydraulic system externally with air to restore pressure. The system’s fine now.” Just as well, because my turn was coming up to ride the bike, and the last thing I fancied on a chilly Misano day was to have the steering freeze on me going into the chicane. I’d been watching the antics of the other journalists taking off down pit lane in a series of wobbles and swerves as they mentally and physically wrestled with the intricacies of Tesi-taming; and thinking back to a year ago when I rode the ELF, I remembered that low-speed maneuverability had been poor on that bike, too. Mentally determined not to let the bike get the better of me, as it was so obviously doing to many of the others out on the track that day, I suited up and set off.

I quickly learned that the Tesi is the most unusual bike to actually ride that I’ve ever sat on, and that includes the ELF. I started off all right, at least, having noticed that a handful of clutch and lots of revs was the hot tip for getting off the mark in a straight line without tipping over. But then, while easing through the first left/right complex just after the pits in second gear, I almost lost control. The bike seemed to knife under me, and my panicky over-compensation nearly had me steering wildly off the edge of the track. After recovering, I drove gingerly through the next few corners before approaching the long left sweeper leading onto the main straight. Finding myself a gear too high and out of the suprisingly narrow powerband (Bimota had been experimenting with exhausts in a largely successful effort to find factory-level power of 128 bhp at 12,800 rpm, but it had resulted in a hole in the powerband between 8000 and 10,200 rpm), I decided just to muddle around the corner on this exploratory lap and almost ended up understeering off the track because of my laziness. But at the end of the straight I changed down to first, which was one gear too low, and as the Tesi snapped into line and tracked tightly around the horsehoe, I realized I had cracked the secret of riding it.

Because what we have here is the nearest thing to a racing car on two wheels that you’re likely to come across, in terms of track behavior as well as chassis construction. Back in the bad old days, when I raced cars before reforming and taking up two wheels, I learned that the optimum setup was a basic understeerer that you could convert to power oversteer simply by booting the car around corners with the right foot. If you went too far and the back end started hanging out, that was okay, because all you were doing was steering with the throttle—and a touch of opposite lock always looked good in the papers the following week. Overcook it, and an invariably harmless spin was the result. But try all that on a motorcycle and you’ll want to verify that your insurance is fully paid up first.

Perhaps Maurizio Rossi summed it up best when he said that you must be decisive on the Tesi, or the bike will be. Go into a corner a gear too high or with the engine revs too low, and you’ll encounter chronic understeer.

So, as with a racing car, the Tesi requires that you do all your braking in a straight line, then accelerate into the corner with the power on and the engine revving hard. If you try to go into the corner still braking, like you can easily do with the ELF, the dreaded understeer will assert itself and—whoops, here comes the edge of the track again. You have to pick your peel-off point, select your line, then really chuck the bike into the corner with the power on, which, at best, is quite difficult to do on an unfamiliar machine. In the end, though, it’s the only way.

Next time I came around, I hit the sweeper leading onto the straight cranked well over in fourth gear with the engine chiming away at 12,500 rpm. This time the Tesi tracked dead-true along my predetermined line and didn’t require much effort to do so. And the steering even seemed light and precise at high speed; but at low speed, fumbling through the chicane on a slightly greasy track, all the original uncertainty and lack of directional stability returned, accompanied by a disturbingly sudden transition from upright to lean-in.

I gradually got to feel more at home on the bike, but it’s still not a machine for riding half-heartedly. Nor is the Tesi a forgiving motorcycle: It requires a degree of commitment and single-mindedness from the rider quite unlike any other machine I’ve ever ridden.

So, too, is the riding position rather strange, with the height of the V-Four engine dictating a tallish seat. The rider is positioned quite far forward, looking down on the handlebars, while the bulbous, 24liter fuel tank with its deeply sculptured sides nestles tightly into one’s chest; if not for that, I’d have found the riding posture quite tiring, as Rossi does. The Tesi weighs 375 pounds with self-starter, oil and water but no fuel, a figure Martini believes can be reduced to near 330 pounds with some detail development work. Weight distribution is 50/50 on this machine with a 155pound rider (Rossi) in place, compared to 52/48 on the original 400. The wheelbase is as short as that of most 500cc GP bikes at only 54.3 inches, making for a responsive bike in tight corners—provided you keep the power turned on. Compare the weight to the 340 to 350 pounds of the works RS750R Hondas (with-> out a starter motor) and you can see how potentially competitive the Tesi is with only five less horsepower at the present time.

I did sense the bike felt rather tall and top-heavy, leading me to ask Martini if he’d thought of trying to redistribute the fuel load a la ELF to lower the center of gravity. “No,” he replied without hesitation, “because for me the important thing is not to have a super-low cee of gee but to place the center of mass as close to the center of gravity as possible in order to reduce the polar moment of inertia, and to ensure this remains as constant as possible as the fuel load reduces. The fuel tank is located specifically to achieve this aim.” So there.

Remarkably, the light weight has been achieved in spite of the use of steel swingarms front and rear. Steel was chosen after it was found that to achieve the necessary structural rigidity, alloy fabrications had to be so hefty that there was hardly any weight-saving. Only a single water radiator is used, positioned at an angle under the handlebars with the hot air cleverly ducted away to the side before it hits the rider. I could have done with a bit of warmth after a half-dozen laps, but none was forthcoming. The oil cooler sits low, down behind the bottom of the front suspension unit; but in spite of what looks like an oil tank under the seat, the oiling system is not the dry-sump type. So much oil is blown out of the engine through the breather that it’s necessary to catch it in at least a two-liter tank, separate the air from the oil with a series of mesh wires, and provide for gravity return to the sump.

Now for the big question; When can we buy one? Martini smiles enigmatically when you bounce that one off him. “First of all, I want to replace the present chassis with a chrome-moly, tubular one, which will be much less expensive and more suitable for production use. Even alloy-skinned honeycomb costs too much to work with, because you have to fit all the mounting inserts manually, which is a very precise task that takes a lot of time. I’m not yet convinced that carbon fiber is a suitable medium for a motorcycle chassis from the safety standpoint. Carbon’s okay for a closed structure like a car monocoque, but on an open one like a bike frame, which is inherently less rigid, Fm not so sure. Anyway, a tubular frame will only weigh three to four kilograms more, and for road use is much more practical.”

So will there be a Tesi roadster in the future after all? “Well, obviously that’s what we’re all working toward, but it’s some time away. I suppose the Cologne Show in ’86 must be our target, but it all depends on finance and time. I doubt if we’ll use a V-Four engine for the road version; I prefer inline engines anyway, because they’re less complicated and easier to work on. But when and if we do offer a road version of the Tesi, it must be right first time when we put such an unconventional bike bearing the Bimota name on sale to the public. That takes time. And in the meantime, to continue generating cash flow for such a research project, I have to work on more conventional but still excellent machines like the SB5, and come back to the Tesi when I can. But we’ll persevere with it.”

And persevere they must. Because the people at Bimota are fully aware that their traditional market of discerning connoisseurs who can afford the ultimate in sport motorcycles has been seriously eroded by the Japanese in recent years. Take a look at the FJ 1 100 Yamaha, for instance, and you see an assemblyline version of the Bimota at half the price. And while the company will no doubt continue to sell bikes in the interim, Bimota urgently needs once again to offer something distinctive that justifies the hefty price tag its products carry. Permitting a test ride of the Tesi prototype, warts and all in its barely developed form, shows that Bimota has longterm intentions for the bike’s future. And although you certainly couldn’t put the Tesi on the road in its present form, further development will surely work wonders.

While we’re waiting for that to be done, maybe we can help pass the time with a new game; guessing which inline four-cylinder engine will ultimately wind up in a roadster version of the Tesi. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

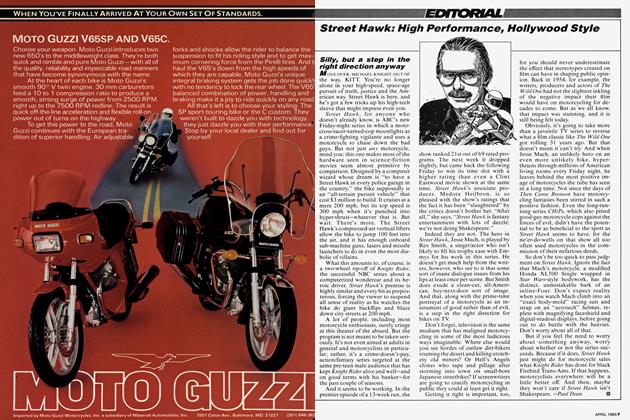

EditorialStreet Hawk: High Performance, Hollywood Style

April 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupBig Brother's Still Watching

April 1985 By David Edwards -

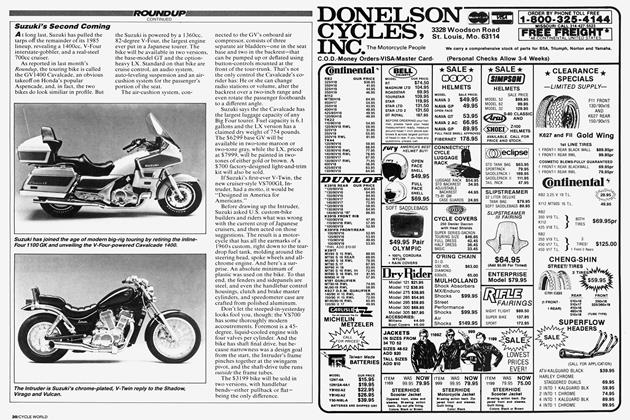

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Second Coming

April 1985 -

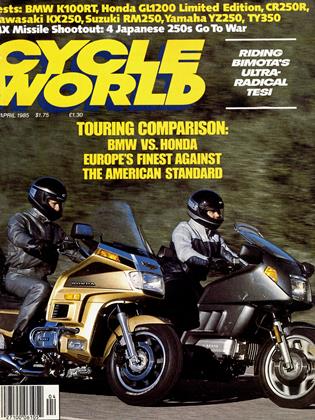

Tests

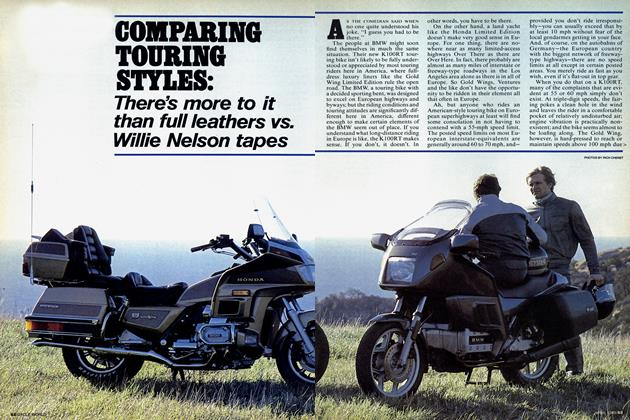

TestsTwo Extremes of Touring:

April 1985 -

Features

FeaturesComparing Touring Styles:

April 1985