THE MAD-MOD OVAL GARDEN

JOHN WAASER

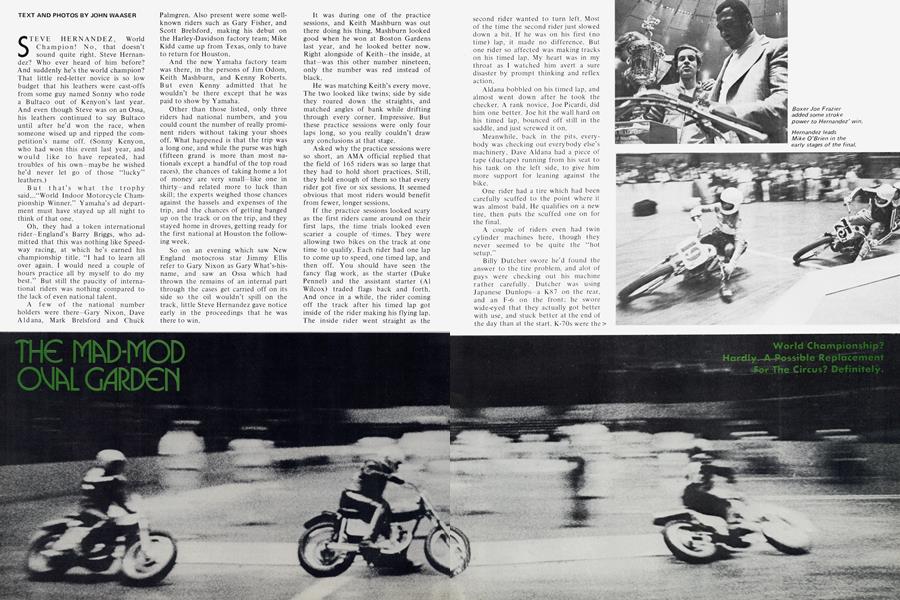

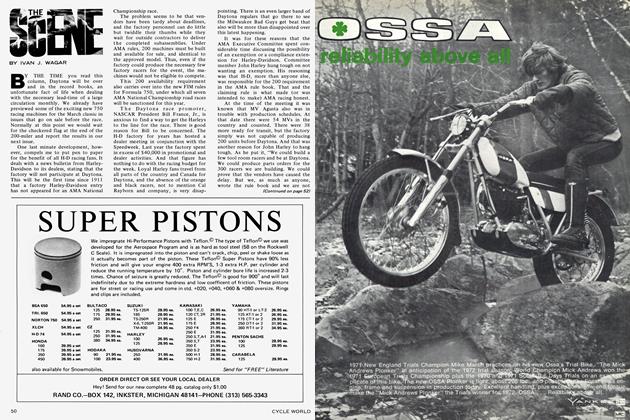

STEVE HERNANDEZ, World Champion! No, that doesn't sound quite right. Steve Hernandez? Who ever heard of him before? And suddenly he's the world champion? That little red-letter novice is so low budget that his leathers were cast-offs from some guy named Sonny who rode a Bultaco out of Kenyon's last year. And even though Steve was on an Ossa, his leathers continued to say Bultaco until after he'd won the race, when someone wised up and ripped the competition's name off. (Sonny Kenyon, who had won this event last year, and would like to have repeated, had troubles of his own-maybe he wished he'd never let go of those "lucky" leathers.)

But that’s what the trophy said...“World Indoor Motorcycle Championship Winner.” Yamaha’s ad department must have stayed up all night to think of that one.

Oh, they had a token international rider—England’s Barry Briggs, who admitted that this was nothing like Speedway racing, at which he’s earned his championship title. “I had to learn all over again. I would need a couple of hours practice all by myself to do my best.” But still the paucity of international riders was nothing compared to the lack of even national talent.

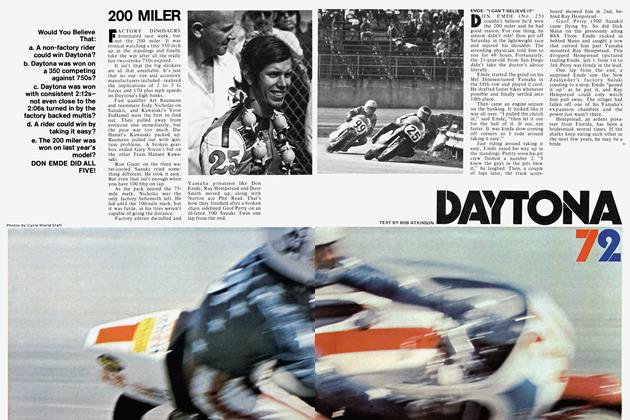

A few of the national number holders were there—Gary Nixon,.Dave Aid ana, Mark Breisford and Chu’ck Palmgren. Also present were some wellknown riders such as Gary Fisher, and Scott Brelsford, making his debut on the Harley-Davidson factory team; Mike Kidd came up from Texas, only to have to return for Houston.

And the new Yamaha factory team was there, in the persons of Jim Odom, Keith Mashburn, and Kenny Roberts. But even Kenny admitted that he wouldn’t be there except that he was paid to show by Yamaha.

Other than those listed, only three riders had national numbers, and you could count the number of really prominent riders without taking your shoes off. What happened is that the trip was a long one, and while the purse was high (fifteen grand is more than most nationals except a handful of the top road races), the chances of taking home a lot of money are very small—like one in thirty—and related more to luck than skill; the experts weighed those chances against the hassels and expenses of the trip, and the chances of getting banged up on the track or on the trip, and they stayed home in droves, getting ready for the first national at Houston the following week.

So on an evening which saw New England motocross star Jimmy Ellis refer to Gary Nixon as Gary What’s-hisname, and saw an Ossa which had thrown the remains of an internal part through the cases get carried off on its side so the oil wouldn’t spill on the track, little Steve Hernandez gave notice early in the proceedings that he was there to win.

It was during one of the practice sessions, and Keith Mashburn was out there doing his thing. Mashburn looked good when he won at Boston Gardens last year, and he looked better now. Right alongside of Keith—the inside, at that—was this other number nineteen, only the number was red instead of black.

He was matching Keith’s every move. The two looked like twins; side by side they roared down the straights, and matched angles of bank while drifting through every corner. Impressive. But these practice sessions were only four laps long, so you really couldn’t draw any conclusions at that stage.

Asked why the practice sessions were so short, an AMA official replied that the field of 165 riders was so large that they had to hold short practices. Still, they held enough of them so that every rider got five or six sessions. It seemed obvious that most riders would benefit from fewer, longer sessions.

If the practice sessions looked scary as the first riders came around on their first laps, the time trials looked even scarier a couple of Times. They were allowing two bikes on the track at one time to qualify. Each rider had one lap to come up to speed, one timed lap, and then off. You should have seen the fancy flag work, as the starter (Duke Pennel) and the assistant starter (AÍ Wilcox) traded flags back and forth. And once in a while, the rider coming off the track after his timed lap got inside of the rider making his flying lap. The inside rider went straight as the second rider wanted to turn left. Most of the time the second rider just slowed down a bit. If he was on his first (no time) lap, it made no difference. But one rider so affected was making tracks on his timed lap. My heart was in my throat as I watched him avert a sure disaster by prompt thinking and reflex action.

World Championship? Hardly.A Possible Replacement For The Circus? Definitely.

Aldana bobbled on his timed lap, and almost went down after he took the checker. A rank novice, Joe Picardi, did him one better. Joe hit the wall hard on his timed lap, bounced off still in the saddle, and just screwed it on.

Meanwhile, back in the pits, everybody was checking out everybody else’s machinery. Dave Aldana had a piece of tape (ductape) running from his seat to his tank on the left side, to give him more support for leaning against the bike.

One rider had a tire which had been carefully scuffed to the point where it was almost bald. He qualifies on a new tire, then puts the scuffed one on for the final.

A couple of riders even had twin cylinder machines here, though they never seemed to be quite the “hot setup.”

Billy Dutcher swore he’d found the answer to the tire problem, and alot of guys were checking out his machine rather carefully. Dutcher was using Japanese Dunlops—a K87 on the rear, and an F-6 on the front; he swore wide-eyed that they actually got better with use, and stuck better at the end of the day than at the start. K-70s were the almost universal footwear of everybody else.

The AMA came in for their share of baubles and brickbats during the evening too. Executive director Russ March, whose toupee keeps getting more obvious as his real hair gets grayer, got himself an award from Yamaha for his devotion to safety in the promotion of motorcycle competition events.

Assistant starter AÍ Wilcox w'ho had been very nearly booed out of a similar event in Philadelphia earlier in the weekend, by all reports, came in for some more static from the stands tonight (“Let’s hear it for AÍ Wilcox! BOOOO” ...etc.)

And the Pit Steward thought he was being cute when he called for a sparkplug for one of the girl entrants: “Who’s got a plug for her? I don’t know what her heat range is—I haven’t had a chance to find out.”

Later when he put Kenny Roberts on an 8-min. clock to change gearing and get to the line for the trophy dash, I asked one of the riders standing around Kenny what the pit steward’s name was. “I think it’s A.....e,” replied the rider, “but don’t quote me on it....”

Referee Charlie Watson, as per usual, received the most criticism. In one case Charlie was right as rain; Gary Fisher had gone down, knocking someone else down, who was in turn hit by Keith Mashburn. As the bikes continued circulating, the three riders struggled.

Fisher was the first one to start to get up. He half got to his feet, looked around, and flopped back on the track, his arms flung over his head, and let his helmet crash loudly to the surface.

It was so obvious that it was a phony, that I was laughing so hard I forgot to get a picture of it. But it wasn’t obvious to the flagman, no sir.

He hopped to, and got that ambulance flag flying fast. The race was stopped, and the stretcher bearers rushed out on the track. Gary hopped to his feet, and grabbed his bike to go racing. Old man Watson, said “no, you’re going home is where you’re going, sonny.”

They lined up the rest of the riders, with Mashburn at the rear of the pack, which didn’t please him a bit, since he’d been in the middle when he went down, and the restart is supposed to be from the lap previous to the stop. Meanwhile, the crowd knew what Fisher had done. This aggressive, likable underdog has shaken up the troops at every race he’s appeared in, and by golly he’s gonna keep it up until someone clips his ears good.

This time he wasn’t listening to Mr. Watson. The crowd cheered for Gary, and booed the AMA. Somebody in the crowd even called Mr. Watson by name, and Charlie got more upset.

But Fisher was ordered out, and he fired up, and rode out, waving to the crowd as he went. The crowd cheered loudly until Gary was out of sight, then jeered the AMA some more. Amidst much clapping of hands and stomping of feet, Gary came back on stage to argue with Russ March.

Meanwhile Bill Dutcher was cleaning his tires, but the other riders were just waiting in line. Fisher finally put on his helmet, and went to the starting line, but was again ejected, and the race started off again without him. Mashburn passed one rider or so, but did not come near qualifying.

When asked about the incident later, Russ March said it is definitely in the rule book that a rider who pretends to be injured to get a race stopped will be disqualified. “If I remember right, Gary Nixon proposed that two years ago....”

Russ indicated that this was the sort of thing the AMA would like to be able to overlook, but they couldn’t because another rider, who thought he might have finished better, could protest. Had Gary laid there, and allowed them to put him on the stretcher, according to Russ, then slowly came to his senses, he might have gotten away with it. In fact, the biggest problem with this event seemed to be that nobody could decide whether it was a “World Indoor Motorcycle Championship,” a 815,000 professional race, or just something to do for fun before the regular season opens.

But while a kid named Jimmy Ellis was getting away with running number zero (how many Yamahas did Jacobson have to give the AMA to get that number, asked the pit wags), and while a guy named Don Brymer couldn’t even swing enough pull to get a hamburger out of the concession stand (they were out), the management of Madison Square Garden was doing their level best to secure bad press for the event. Pre-race publicity releases were clearly the poorest I have ever seen, combining inaccurate facts with poor grammar and unimaginative writing.

While bike mag photographers (some of whose pictures appeared in the program) were refused admission to any acceptable shooting spots, newspaper photographers who regularly cover events at the Garden were allowed everywhere in a case of “you scratch my rear, and i’ll scratch yours,” apparently having a lot to do with advertising.

Yet the newspapers used from one to three photos each, and the New York Times didn’t even bother to identify the riders in the caption, or to show a picture of the winner.

Magazine photographers were kept in severely limited spots, like right behind the corner flagmen, who moved back into your line of sight every time you moved to get a clear view. An AMA staffer with a videocorder also managed to get one of the choicer spots, and when asked how, he replied “1 work here....” One of the more enlightened statements ever issued by Worthington, Ohio, I’m sure.

But the ultimate bad press came just about the time the evening was due to get underway. It was on the 6:30 edition of the channel 7 eyewitness news, which we were watching in the Garden’s press room.

First the announcer referred to the large turnout of riders, then said “Take them and their noisy, polluting machines, and put them under one roof....” This is the same network that brings us Wide World of Sports? The New York Times treated us so-so. “Steve Hernandez capped a noisy, smoky, and exciting evening....”'

So while most of the riders gave the AMA tacit approval (Kenny Roberts: “Yeah, they did OK; it’s hard to run this show...”) nobody could be that kind to the Garden management.

Always a high point at these events are the Mini-Enduro Races. Dave Aldana was doing pirouettes until he spilled it, then Kenny Roberts unsettled Barry Briggs by bumping him very hard several times at the starting line.

So Aldana had to top that with a couple of front wheel wheelies. Then after the race Barry Briggs grabbed a fire extinguisher and tried to squirt his Yammy with it, but was restrained by the officials, who probably didn’t have another extinguisher available.

Then, since there were two girls entered, Sammie Dunn and Debbie Seiden, and since neither of them had qualified, promoter Don Brymer decided the crowd would like to see a match race, and lined them up. But Sammie’s bike wouldn’t fire, and after they wasted much time on that they flagged them off, only to bring them back later on Mini-Enduros. This was supposed to be a five lap event, but it was flagged at the end of three laps, when Sammie went down. So Debbie was clearly the winner.

The heats and semis were quickly gotten out of the way. Mike Kidd won the fastest heat, and looked super good all evening. But he was second in the slowest semi, which qualified him 6th at the inside of the second row, where he finished. Roberts also looked really good all evening.

But he had to keep on lowering his gearing. When he finally figured that something was wrong, he didn’t have the time to check it out. He qualified 11th for the 10-man final, so he finally had the time to check it out; the clip which holds the needle in the carburetor had fallen out. The only other rider who really looked that good all night was Hernandez.

Fastest qualifier, heat winner, semi winner (second fastest heat, fastest semi), trophy dash winner. He looked good sitting on the pole for the final. And when the riders started their bikes after some pre-race photography and introductions, the lineup sounded more tense than any previous lineup.

Steve got the lead off the line, and that was the race. Mike O’Brien pushed him hard all the way, but Steve never made that one mistake Mike needed. Rick Hocking and Robert E. Lee dueled for 3rd, with the southern general taking it away from Rick. Dave Aldana may have turned in the most impressive performance of the final, starting in 9th, and finishing 5th. But the duel for 1st was tight enough so that nobody watched that far back.

The crowd of 13,871 (several thousand below capacity) seemed to have thinned before the finals, and rushed out long before the photographers would let Steve out of the center of the track. New York had seen another Silver Cup.

World Championship racing it’s not; but the Yamaha Silver Cup might just replace the circus as the greatest show on earth. Check it out when it comes to your town.