FEEDBACK

Readers are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, funkiness, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but illfounded invectives; include useful facts like miles on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

AMEN, THREE TIMES

Re: Feedback, CYCLE WORLD's February issue, "Letter from a Frustrated Partsman"—AMEN! ! !

Truly yours, frustrated partsmen Robert Salmon Bix Dunlavy Art Rodriguez San Fernando, Calif.

VIEW FROM ENGLAND

I have been riding road motorcycles (amongst others) for 15 years, always owning one decent machine, plus a hack for commuting, etc.

The following large capacity machines were bought new by me—with pertinent comments about them....

1963 Venom Clubman Veeline —Kept in standard trim. Reliable, beautiful road-holding, handling and braking. Adv. 60 Imp. mpg. Max. 105 mph. Approximate cruising 85-90 mph. Deceptively rapid acceleration from a smooth engine. Sold after 35,000 miles and still fairly oil tight!

1965 Venom Thruxton—Kept standard again. Very unreliable. Five major engine failures-replaced by factory. Road-holding, handling, etc., not quite as good as the Clubman—different sizes and makes of tires and different rear dampers than fitted by makers helped counteract this. Braking better than Clubman. Adv. 50 Imp. mpg. Max. 105 mph. Aproximate cruising 85-90 mph. Very good acceleration from 30 mph upward. This particular model appeared to be a "rogue"—but others were O.K. Still fairly oil tight when sold after 20,000 miles.

1967 Triumph 650 Bonneville T120-Largely converted to full production racing spec. Reliable—beautiful road-holding, handling and braking in P.R. spec. Adv. 35-40 mpg. Max. approx. 120 mph. Cruising about 100 mph. Very fast all-round motorcycle. Was oil tight when sold after 30,000 miles.

(Continued on page 30)

Continued from page 28

1970 500cc Kawasaki Mach III—Reliable. Dangerous road-holding and handling qualities—even when converted with British tires and suspension. Very slow steering, and performed alarming unwanted maneuvers when shutting off from high speed.

The brakes on the Kawasaki failed badly, even with Ferodo AM4 linings in the front and Ferodo AM3 linings on rear. Headlamp changed to Lucus 700 unit to overcome glowworm-type headlight. Nevertheless, it was a beautiful engine, very smooth, with terrific performance, providing it was driven within its power band 5750-8250 (coils and points model). Otherwise fairly slow for a 500. This would be a great motorcycle if fitted with a good British chassis. (Rule Britannia!) Adv. 40-35 mpg. Max 120-125 mph. Cruising speed 100 mph. Sold after only 5000 miles in fear of life and limb—but perfectly oil tight.

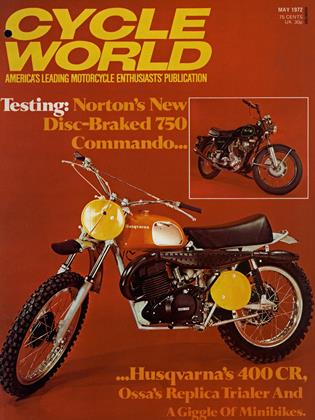

1971 Norton Commando Roadster Mark II—Reliable so far. Road-holding and steering a revelation after the Mach III. Braking even worse than Mach III but the factory is being very helpful and is working on the problem. Handlebars changed for flat Honda CB 175 ones. How you ride far and fast with standard bars beats me! Headlamp changed to Lucus sealed beam (off a Mini Car), and flashers fitted. These are marvelous at night on unlit roads. The ride is smooth from 3000 rpm up. The mountings and shimming on my motorcycle are tighter than standard. Engine has enormous power—right through the range—making it a lazy bike to drive, but very fast on the road. An uncomfortable dual seat is fitted.

Adv. 40-45 mpg. Max. 110 mph. (Revs to 7000 in top but not above.) Cruising about 90 mph but not too sure yet. High oil consumption but the bike itself is oil tight. A fast all-round motorcycle. Miles to date, 5000.

L. R. H. Strutt Surrey, England

CB 500 SHIFT KIT

In your Feb. '72 issue, Feedback Dept., page 22, you printed a letter regarding the Honda 500 Shift Kit.

Russ Hamiliton stated that the Clutch Modification Kit dealer cost was $20.45, and that it is not a warranty item. This is incorrect!

I would like to set the record straight. I have a 1971 CB 500, the best bike I have ever owned, but mine was one of the early ones without the clutch mod kit being factory installed.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 30

I am a member of IFOA. When I received their Tech Notice stating that Honda did have a clutch mod kit, I immediately contacted my dealer. The dealer knew of the kit but said that they had been on back order for 2-1/2 months. My dealer indicated that the kit was a warranty item. I called American Honda at Gardena, Calif., (213) 327-8280, Ext. 334, and talked with Mrs. Woods in the Parts Dept. The kit was available and in stock at AHC, Gardena, but must be special ordered by the dealer who is to install the kit. Within a few days my dealer had received and installed the kit at no cost.

AHC also has a warranty anti-smoking kit for the early 500s including new rings and valve guide seals, and will be installed at no cost to the owner.

I found American Honda Corp. Head Office to be very cooperative and willing to help! I would recommend anyone with a parts or warranty problem to contact AHC at the above number.

David L. Young Beaumont, Calif.

A HARD-PUSHED 125!

We thought you might be interested in the problems the two of us (we co-own and race the bike) have had with a 1971 Yamaha AT-1 MX, the 125cc motocrosser. Bought new in early May, the bike has since the beginning been a pain to start, and has not improved any after two top to bottom tuneups that included new points, condenser, coil, etc. Handling with the stock trials tires is downright dangerous, so early in the game we split for full knobs front and rear, plus a 21-in. front wheel. Forks are soft, bottom early, but livable if your standards aren't too high or you're too poor to replace or modify them. Rear shocks: WHAT rear shocks?

The bike sorely needs a good diet. Ours lost: heavy 19-in. front wheel and tire, front fender, numerous useless brackets left over from the street version, oil tank (too high, big and heavy) and the stock air cleaner box which carries a near useless (and restricting) filter. However, the airbox is easy to waterproof so don't throw it away as you may need it again.

Our bike broke the following: the swinging arm, one handlebar, countless levers, countless chains, the left side cover gained several holes from the afore-mentioned chain throwing, the expansion chamber heat shield cracked into pieces, the rubber strap that holds the gas tank, sawed in two, shift lever got sheared off even with the case, and last but not least (we're still racing it), a tiny piece of metal on the crankshaft called the woodruff key (holds the magneto in place) disintegrated. Some of the breakage can be attributed to normal race wear and tear—some of it is almost freakish. Item: the handlebar levers should be replaced with bendable types as soon as possible; the stock Yamaha levers break easily, and they charge two legs and seven fingers for replacement levers at your friendly Yamaha dealer.

Other problems: handling is poor to fair depending on what you're comparing it to. We lengthened our swinging arm an inch after being tossed-off too often landing from hard jumps. Cured the problem. Stock swinging arms will begin to bend up at the ends after a few good races; should have brace welded on. Heavy, but beats breaking the swinging arm (as ours did). Expect shifting troubles, like a vague 2nd gear for instance. Unfortunately, second is about the most used gear,when you can find it, since first is short on poop, and third a mite high. In the same vein, we've been plagued lately with the trans popping out of gear—chain? Shifter dogs? We don't know yet.

Trivia and conclusion: The seat is great! Stock pegs slippery. Countershaft sprocket too hard to get to. Could use wider and sturdier handlebars. Beautiful looking machine. Power is not as great nor as controllable as say a Bultaco's. Still, it's fast when running right. Realiability (to make an understatement) has been our main problem. A dried-up O-ring in the carb, and tired sparkplugs (after two races?) were both at times thought to be the cause of the hard starting. Result: it starts a little easier than it did before.

(Continued on page 34)

Continued from page 32

In light of the modifications needed, overall quality and reliability it's questionable whether the bike is the bargain racer it's sometimes advertised as. However, it does force you to learn the tricks of the race pit mechanic.

Denis Schmiddin Steve Paske Madison, Wis.

It sounds like you two are getting your first lessons in racing bike maintenance. The harder y ou ride, the harder you have to work to keep your bike in shape.

Example: A set of plugs a race is not unusual. Don't be too hard in judging your 125. More experienced riders than you consider some of the problems you mentioned a matter of course. Read "Violation Of An Ossa" (April '71) to see what we mean.— Ed.

BMW-OFF THE PATH?

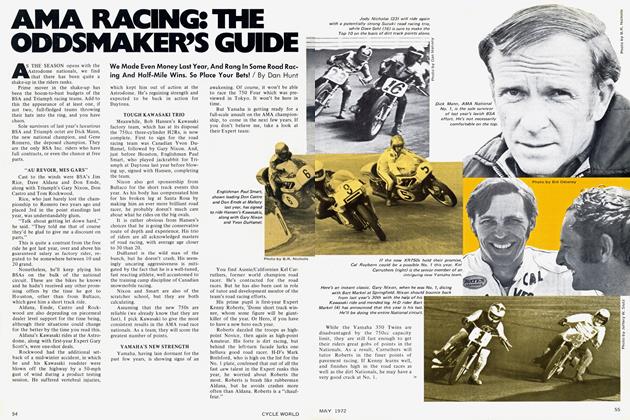

There has been considerable unrest and dissatisfaction amongst members of the BMW motorcycling fraternity with which, as president of the Madison BMW Club, Ltd., and a national officer in BMW Owners of America, I have become familiar. This unrest centers around the trend that Bayerische Motoren Werke seems to be following ever since it introduced the new BMW line in CYCLE WORLD'S issue in September, 1969. Preliminary response to the 1972 BMW line, shown in CYCLE WORLD of November, 1971, indicates this unrest will only grow worse. What is the cause of this worried concern by BMW riders? Let me try to spell it out.

In the Paris automobile show of 1923, a startling innovative motorcycle became the center of attention. It was the design of Max Fritz, an engineer whose specialty was the design of aircraft engines for the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, an offshoot of which was the later BMW company. That motorcycle was the BMW model R32, and it had some strange features: a horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder engine placed transversely in the frame, a driveshaft, unit construction, and a handsome black-with-white-pinstriping paint job. In the next few years after 1923, Fritz worked hard on perfecting his design with a heavy emphasis on reliability, and he proved it in European and English races during the '20s.

In the 1930s, BMW invented the first telescopic fork, which is now used almost universally by all brands, and developed the touring motorcycle "par excellence." During World War II, BMW's enviable record of reliability was bolstered by motorcycle performances in the deserts of Northern Africa, performances unequalled by American military motorcycles. Even today, World War II R75M model BMWs are held in high regard in Europe and prized by owners lucky enough to own them.

In the 1950s, after BMW was able to resume motorcycle manufacture, the company produced the first of the finest, highest-quality touring motorcycles the world has ever seen. This series started with the 1950 R51/2 and 1951 R67, and later was modified with Earles forks and a swinging arm rear suspension.

During all this time, with few exceptions, the rest of the world produced motorcycles of a different kind. With emphasis on high compression, peak horsepower, quick handling, the use of chain drives, and with little regard for vibration or touring, these motorcycles shared only the concept of two wheels and an engine with BMW. During the '20s, the '30s, the '40s, the '50s and the '60s, BMW produced a motorcycle apart from the others which was uniquely suited to the rider who insisted on maximum reliability, comfort and quality, and minimum noise, vibration and maintenance. Conservative development was the nature of BMW, as well as stubborn adherence to a unique product whose value and quality was proven and admired. BMW riders became both famous and infamous for their refusal to desert their brand and insistence on its superiority.

Then came the candy-apple, chromecovered, peak-power revolution of the '60s. Japan invaded the U.S.A. and its uncanny ability to sniff out the youth market's dollars caused shakings of the foundations of all the competitors. Where Japan once imitated European motorcycles, Europe started to ape Japan's. Today you can look at nearly any English bike of this model year and you will find its design hard to distinguish from Japan's. Apparently, so it goes in Germany as well.

When, in late 1969, the new BMWs were launched on a curious public, BMW owners were visibly and audibly shaken. Granted, their pride-and-joy BMW was due for a remodeling, but many felt BMW went too far away from its tradition. In pursuing a "sporty" image, it was felt, too many things were sacrificed. Plastic parts replaced steel. A new seat proved too unyielding for many touring riders. Leaky seals and front-end wobbles plagued many owners of the new models. Fenders didn't stop much flying mud anymore. Saddlebags proved hard to mount over upswept mufflers (a condition much worse for 1972). But perhaps worst of all, the insidious influence of oriental styling was detected, ever so slightly, in the new BMW design. Many critics said they found where the famous "Honda hump" went. On top of this, BMW prices skyrocketed. Suddenly Moto Guzzi found a new market for its heavy and stable V-750 Ambassador, as disenchanted BMW owners cast their votes the only way they could . . . with their dollars.

(Continued on page 36)

Continued from page 34

In the 1972 models, BMW has confirmed the trend so that even the most passionate devotee of the marque can see the handwriting on the wall. The pipes are swept even higher, and generous acres of chrome give the bike the aspect of a cast-off 1965 Honda design. The famous BMW pinstriping, a hallmark for generations of riders, must now be found partially hidden under brackets and seats and is completely gone from the gasoline tank. A shrinking of the fuel capacity tells prospective owners that here is the beginning of a city bike, and the touring bike is dying. This is reaffirmed when he thinks about putting his saddlebags on this bike or wonders whether a fairing will induce that 1970's high-speed wobble again. But quickly, the dealer assures the curious that this new 1972 BMW is available in many colors! Chrome and candy-apple all over again!

I've written your column to tell you how it looks from my saddle. BMW is not lost yet ... far from it. The shaft drive remains, even though with touchy seals. The horizontal engine remains, with high peak horsepower. But I have the concern of a fellow who's worried about his life-long friend who's veering off the proper road. There is too much strength and too much that's right in the long BMW tradition. I want to see that strength and those virtues remain.

Jeffrey Dean Madison, Wis.