THE TRAILRIDER

BOB HICKS

Reader's of February's interview of Bob Hicks have had a taste of this rider/publisher/organizer, who is part and parcel of the New England brand of motorcycle sport. But his interest, his personal philosophy go far behind the parochial. Now we offer you the whole meal-a column by Hicks on diverse topics. You'll enjoy him. He tells a good tale.-Ed.

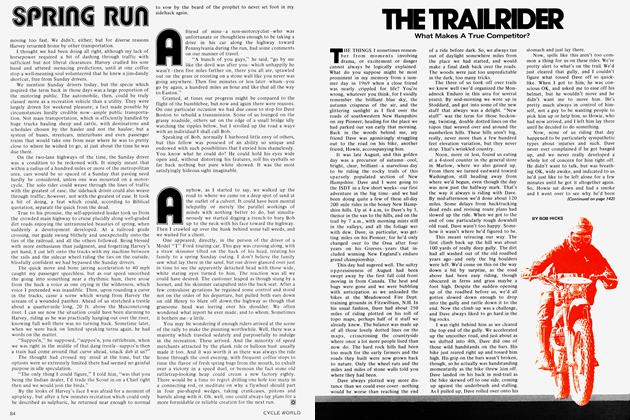

THHE of the LADY rambling WHO old came frame to house the door was perhaps in her mid-60s.She was very pleasant and motherly in appearance. David had knocked, and it was he who undertook to tell her what we had in mind. We had just come out here at the end of about three miles of classic old New England woods road, eroded, boney riding steadily downhill from the high ground into this small river valley. The last hundred feet of what was obviously an abandoned old road had run right through the yard of this house; winter firewood was piled alongside both boundary walls. If we were going to include this in our Monadnock Enduro we’d have to surely gain the approval of the people in this house.

“Well, that sounds all right to me,” the lady said to David when he had finished explaining our interest in this old road. “That road was thrown up years ago, all the way to the power line up above. We own it now, but I can’t see any harm in you boys running your motorcycles up there. Lord knows, there’s always someone going up there, or trying, in jeeps, or motorcycles, even once in a while in a car.” Obviously we were in luck; this lady didn’t object to people using her land. “Ed sorta like for Henry to say, though” was her windup. Henry? Must be her husband.

“No need to commit yourself now,” David was saying. “We can come back when Henry is here to get his OK.”

This obviously relieved the lady, for she was wanting to be considerate of our request but not certain she should authorize 200 motorcycles going up that trail. “Oh, that’ll be fine, just fine,” she replied. “Maybe Henry will want to join you.” Join us? How? David asked her politely in what way Henry might wish to join us.

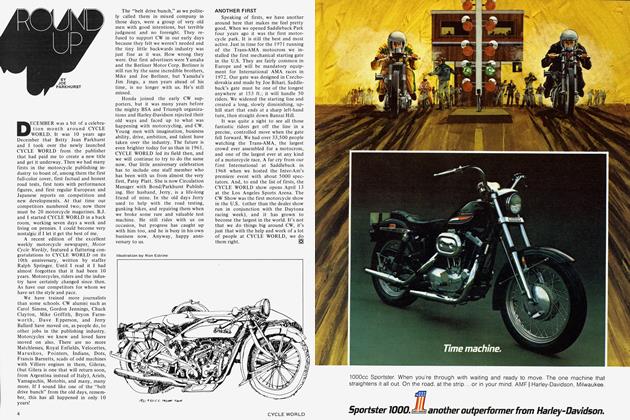

“Oh, he’d get out his old bike if he’d a mind to," she explained. There in the open garage door, if you looked care fully, was a rather tatty old Montesa, perhaps a 1964 model. "My son owns that bike but he's not around here now, and Henry sometimes takes it up back to look around." Yes, maybe Henry would indeed join us on the Monadnock Enduro, at least for a ways. * * *

“Yes, you can ride through. Just go around the end of the cable. That’s up to keep out the lovers; they trash up the woods pretty bad, especially those group gropes they have.” The forest ranger at Willard Brook State Forest seemed to like bikers. We had asked permission to ride through this section because the entrance was cabled.

“Almost as many bikes as horses use this place now,” the ranger volunteered. “And bikes aren’t causing us the grief the horses have,” he continued, chuckling a bit. The chuckle intrigued us, so we asked, “How so?”

“Well, a while back we got a copy of a fancy letter written to the Commissioner by some big shot in Cambridge. Had a bunch of degrees and such written after his name. Seems he had brought his family hiking up here one weekend, and he was pretty mad about all the horse manure on the paths.” At the recollection, the ranger chuckled again.

“No kidding?” we volunteered. “What’d he expect you guys to do, clean up after the horses so’s not to offend his delicate sensibilities?”

“Yep. Guess we’re supposed to follow along with a wheelbarrow and shovels, sort of a sparrow duty. Can’t have those city folks getting too close a look at real nature.”

The sign at the barely visible entrance to this old road that crossed the low Blue Hills area in this part of New Hampshire read, “Road Closed, Subject to Gates & Bars.” This meant it was still a public way, but the abutters could put up fences to control livestock crossing the old way if they put in barways or gates to let the public that might come along pass through. A funny thing about this area as we studied it earlier on the topographical maps was how all the present roads ran from southeast to northwest, and all the roads that used to run from southwest to northeast were now discontinued, only maintained into the last inhabited home on each end.

Soon enough we came to a double barway. Obviously this allowed cattlefrom the farm to the right to get to the pasture on the left. We opened the bars and wheeled our bikes through. As we replaced the bars, the farmer approached. He was darkly tanned and very rugged looking, and seemed congenial enough.

“Just wanted to be sure you boys shut the bars,” he volunteered as he came up to us. We had not yet started the bikes. “Those bikes sure are changed since I used to ride,” he went on. This is a frequent experience with people who grew up around World War I. “Yep, I haven’t ridden a motorcycle since 1919,” he went on. That’s 50 years ago, we thought! He was older than he looked, more like 70 than the 50-ish we’d first estimated.

We asked him what he’d ridden, and that opened up the gates. He wasn’t gabby, but he was obviously enjoying reminiscing about his bikes. He'd had several as he grew up on this very farm he still owned; it had been his dad's place. Finally, right after the great war, he'd gotten married and sold the bike to buy furniture. Somehow times haven't changed a bit.

Talking It Up To Blaze A Trail

We accidentally blundered into this guy’s back yard one day, following a barely visible trail in the Harold Parker State Forest. Only 20 miles from Boston, this was still semi-rural, but suburbanites were moving in fast. The owner was standing down his driveway with a boy of maybe 14, most likely his son. Well, we went over to him to apologize for popping out on him this Sunday morning.

He wasn’t having any. “This is private property, and you’re trespassing,” he announced belligerently as we came up. He reached for my face shield; I still had my helmet on. Guess he wanted to get a better look at my face. As he actually grabbed the shield, I told him to keep his hands off, Fd take my helmet off myself.

Well, he wasn’t going to let me explain anything, about how we’d accidentally come out here, or about how we were sorry to have bothered him. “Let me see your papers,” he demanded in a still belligerent voice. The boy looked on uneasily. There were three of us, and maybe we might just beat up his old man.

“I only show my papers to the police,” I told him. Once you let this sort of guy get your license and registration in his hands, just try to get it back without force. “Call the police to come over; I’ll show them my papers,” I went on. “Or, if you like, copy off my license plate number. Also, I’ll give you my name and address, if you have something to write with.” Obviously, he didn’t, and was out of luck on that without leaving us to go to the house a hundred feet away.

“The state police look after this place,” he went on, trying to scare us apparently. “I’m reporting you to them; we’ll put a stop to this.”

“Why don’t you post that road at your boundary, or put up a gate,” we asked. Obviously he’d had run-ins with horsemen too, for the old trail from the state land led right into his yard without warning or barrier. For this reason, I cared not if he called the cops, we were trespassing on unposted land, and all that could be done was that we would be required to leave. This we were trying to do.

I asked him which way he wanted us to leave, out the driveway, or back the way we’d come. He didn’t want us to leave, it seemed, but was still stuck in his conundrum about how to call the cops. We weren’t going to wait around for him to decide, so I put my helmet back on, and told him, “We’re going now, out your driveway. If you get the police, give them my number.” Then we rode off while he stood there furious. Momentarily he’d tried to block our exit, but three bikes are hard to stop, and we easily rode around him.

I never heard from the Andover police.

Farnum St. showed on the map as a discontinued town road, a double dotted line. Here in suburban Boston country you have to take your trail riding where you find it. As Al and I rode past the farm at the end of the maintained road, an elderly man in bib overalls on a tractor at the farm entrance waved us down.

“You can’t ride down there,” he hollered, as he climbed down off the John Deere. “That’s private road now, and I don’t want none of you motorcycle fellows riding on my land.” He sounded pretty determined.

We stopped our bikes, and got off. “Okay, we’ll turn around,” we replied. “We were just checking out this old Farnum Rd. on our map here. It looked like it might be an old town road.” We unrolled the topo from the carrying tube, and showed it to him.

“My name’s Farnum,” he said, much to our surprise. “And that road was named by my granddad when it was opened. Used to be our farm road, then it was opened up to the public when my dad was a boy, and now it’s been thrown up and come back to me. It ain’t open no more.”

The smell of new-mown hay was very strong around us, and AÍ, who grew up on, and later owned for a while, a small farm, remarked on the high alfalfa content the hay seemed to have. Well, this lit up Mr. Farnum’s eyes, and off he went onto a discourse on the troubles of trying to farm with the city people moving in all around. It was getting hard to hold onto the farm now, what with local taxes going sky high as the land was sold off to developers. All them kids for schools, and the town water, and the big police department, etc.

Well, we must have talked about the bad scene all those city people were making for a hard working farmer for a half hour. We wrapped it up, and then said, “Well, Mr. Farnum, it’s been nice talking with you. We’ll head back now, I guess.”

“Well now, look, you boys, you can go on down the old road here if you want,” he volunteered to our amazement. “I got a sawmill down there with a $3000 diesel in it, and there’s been some vandalizing. I don’t want people going by it. Out of sight, out of mind, you know.” He was actually confiding in us now.

“Fact is, you can ride through when you happen to be by here, but I don’t want just anybody coming by, so don’t go telling everybody about it.” Mr. Farnum was now our friend, and we were being offered exclusive trail-riding rights to his road.

He had a purpose too, we found out. “If you happen to see anyone down there around my mill, just drop back and let me know, is all I ask,” he concluded. So, we would be occasional watchdogs for Mr. Farnum’s mill, and could use Mr. Farnum’s road when we wished. Not a bad trade, not bad at all.

Talk to the people along the trails; get to know them better. You may meet a few who are bummers, but you'll find most are nice enough when they find out you're people like them, and not some sort of anonymous menace roaring past in a cloud of dust and smoke and noise. Remember, the people own the places you want to ride on. They might as well become your friends.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue