BERKSHIRE TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL TRIAL

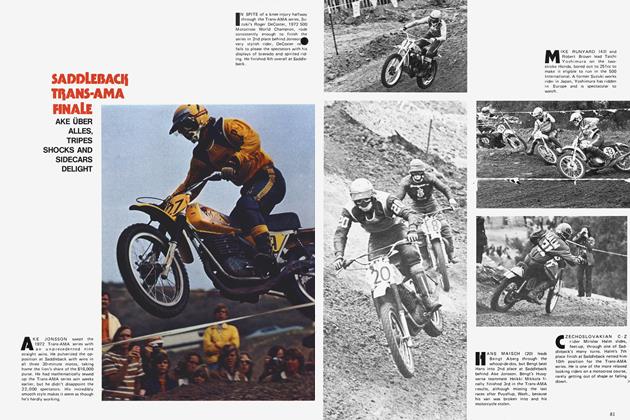

An Impressive Roster Of America's Finest Endurance Riders Mix it With The Duffers In New England's Warm-Up Event For The ISDT

DAN HUNT

SHOULD THERE EVER be an International Six Day Trial run in the United States, it will undoubtedly be run in the Berkshires.

One reason is the terrain. The Berkshires are just as soggy and hilly as the terrain of Europe, Scandinavia and Great Britain, where this prestigious spectacle of stamina, perseverance, reliability and backwoods ingenuity is run from year to year.

Another is the very existence and growth of the Berkshire Two-Day Trial. After six years of running, it has become an accepted part of New England life. Just like its European counterpart, it uses the whole countryside. It rambles, sloshes and snakes its way through the northwest quarter of Massachusetts, through vibrant, dripping stands of woods that reach out to tear at your handlebars and send you tumbling into the undergrowth, up a muddy lane that has been churned to a rutted bog by the melting frost from a New England winter, down a rocky trail that follows a crackling powerline into a storm-threatened valley. The countryside is perpetually at war with itself, although you can’t see it. Green is green, always the same. But bush fights tree, and branch fights branch. All of them fight at your motorcycle.

Just when your strength is sapped, when the prospect of continued forward motion is reduced to despair, a little red arrow directs you onto a paved highway. Rest at last. You whistle along a lonely back road as fast as you dare, trying to make up time. Your involvement is so complete you ignore the facts of your surroundings. You pass near the town of Lee, where Arlo Guthrie got busted by Officer Obie for dumping the garbage from Alice’s Restaurant, but you are unaware. As you approach the hillclimb speed test near Lenox, you couldn’t give less of a damn that you are riding on hallowed cultural ground, near Tanglewood, summer home of the Boston Symphony, near the restored red cottage of Nathaniel Hawthorne, or near Jacob’s Pillow. To muck about in the damp Spring on a motorcycle is like having sex with nature, a holy relationship, based on love of physical life, empathy with the land.

It is not hard to see some of that empathy and devotion in Allen Eames, who laid out the original Berkshire trial in 1966. It was a one-day affair then; 114 riders entered. He had to consult with property owners, some of them hill people who have little to do with civilization, much less motorcycling. Local law officials were asked for assistance.He spent hundreds of hours charting and riding trails. This task has grown larger each year as the trial has expanded. Intersport promoter Bob Hicks takes part in these arrangements, which include the placing of more than 3000 red arrows pointing the way on the present two-day 320-mile course, and arranging for computer transmission facilities to provide almost instant computation of results. Keeping the trails open, for casual riding as well as for the trial, demands a constant public relations effort on the part of both Hicks and Eames. Just one rider—if he is destructive or disturbs a landowner with an unnecessarily noisy exhaust—can ruin weeks of work. But Hicks says that the necessary ambience has been achieved: “The people who live here feel that the Berkshire Two-Day is an integral part of their life. We have established our rightof-way, so to speak, and once you’re in, it’s very hard to be kicked out.”

The Berkshire was conceived to give the average enduro enthusiast a taste of an overland rally run according to European rules. In both the American enduro and European endurance trial (its meaning is clearer if you translate the French equivalent, tout terrain, which means all-terrain rally), you must follow a marked course while conforming to a set average speed. Checkpoints are placed along the way to time your arrival.

But there is a distinct difference between American (AMA) and European (FIM) rules regarding all-terrain trials. In the American variety, you must arrive at the checkpoint almost exactly on time; you may arrive neither early nor late without being penalized. In the European trial, you are penalized only for arriving late.

This difference is subtle, but it has a clear effect. The American enduro is a clock-watcher’s nightmare. Not only do you have to be a skillful rider to maintain a decent pace through rough terrain, but you have to have the accounting aptitude of a CPA as well. Personally, this aspect of the AMA enduro has always put me off, for it tends to detract from the real essence of overland endurance competition—riding skill and mechanical ingenuity. And keeping numbers in your head while battling your way to a checkpoint is not my idea of fun.

In the European counterpart, it is not necessary to carry so much as a watch. You ride somewhat faster than the established average speed for a 30or 40-mile section, and if you arrive early at the checkpoint, you may rest. Or you may conduct necessary adjustments on your motorcycle. Sections may be made somewhat faster, and the event becomes more purely a test of man and machine.

In practice, the average speeds used in an AMA enduro vary from 20 to 24 to 27 mph. Some sections of this year’s Hi-Mountain Enduro in California were marked for an average of 20 mph. Yet the Berkshire, run in much slower terrain, included sections of 30 mph.

There is another difference in the European endurance trial. Special sections are included to break ties: these involve timed cross-country speed tests or hillclimbs; the fastest rider gets the best score. If several competitors finish the course without incurring any penalties for lateness, the resulting tie would be broken by the special tests. Whoever showed the best combined score in all the special tests would win. There is still another tiebreaker in the form of bonus points for starting your motorcycle quickly at the beginning of the day and for having your lighting and horn equipment in operation at the completion of the run.

Because of its resemblance to the European trial (of which the ISDT is the best-known), the Berkshire has acquired an added dimension. It has become a warm-up event for ISDT competitors from the United States. American participation in the ISDT has grown at such a rate that there may be as many as 40 entrants starting in this year’s ISDT, which will be held in Spain in October.

As a result, you can readily see two different philosophies of competition extant in the Berkshire. One is the “duffer” philosophy, exemplified by the guy who wants to ride the event for fun. Contrasting greatly with this is the efficient professionalism of individual and sponsored riders who enter the Berkshire knowing that their performance in the event will be an important consideration in whether or not they are picked for one of the American ISDT teams. An odd dozen of the competitors at the Berkshire this year have already competed in the ISDT, earning Gold or Silver medals.

The organizers have had to take this new professionalism into account. Thus, the Berkshire has become more demanding each year. Naturally, the duffers (use of this word is not meant to be insulting) are the ones that suffer. They barely get more than a few miles. Eames and Hicks struck a nice medium this year by making the first day’s course moderately easy and winding it up with a tough finishing section. So the best duffers got through one day at least and could thus return home happy, pfoclaiming, “Yup, I rode the Berkshire.” Nonetheless, of 370 starters, only 261 made it to the hillclimb special test at Lenox on the first day. it was only 158 miles out from the start.

Only 43 made it to the finish in medal time on the second day, designed to be even tougher and, because of a tiring final section, allowed only those riders with a sufficient reserve of strength and speed to finish within gold medal time, i.e., to “zero” the trial by being on time at every checkpoint.

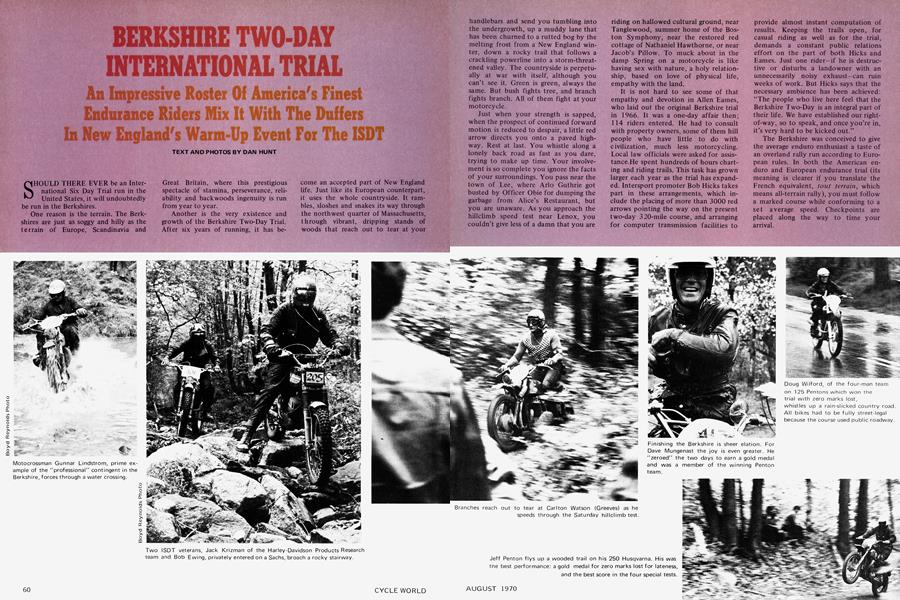

Only 10 competitors had the distinction of winning gold medals in this year’s Berkshire, which would lead one to believe it was a very rough run, indeed. Not so for motocross/ISDT ace Gunnar Lindstrom. The transplanted Swedish American, riding a 360 for the Husqvarna team, commented that it was “lots of fun,” only two minutes after slamming into the finish check in a terrifying feet-up brakeslide. But that’s the amiable Gunnar for you. Everything’s fun for this chipmunk-faced, spectacled Swede-crashing, splashing and constantly being out of shape in a super fast way. What other comment can you expect from a tireless superhuman who spends the greater part of two days on his back wheel at full throttle? However, four penalty marks incurred as he waited to replace a master link lost in a speed test turned his Gold to Silver.

Husqvarna teammate Lars Larson also found time to joke at the finish line, as he worked on his 250 to get his lights working for the final equipment check. A sweet, young kibitzer enthusiastically explained how many bonus points he would get, tediously itemizing them for each piece of equipment.

With a perfectly straight face, and disarming broken English, he asked her, “If my lights is vorking but the engine is not running, do I get some extra points?”

“Oh...well, no,” she said. “You have to go across the finish line with your engine running.”

“But I think I should get some extra points if my lights is vorking and my engine is not running,” he insisted.

She didn’t understand this at all, so he explained:

“It’s only right. The motorcycle has no battery. If the engine isn’t running, the lights don’t vork. So I think I should get some extra points if I can make the lights vork without the engine running, no?”

Just as she realized she’d been had, Lars broke out laughing, fired up his machine and rode into the check. His lights didn’t work. But it didn’t much matter. Seven minutes lost on Saturday as he nursed a broken magneto reduced his prize to a Silver.

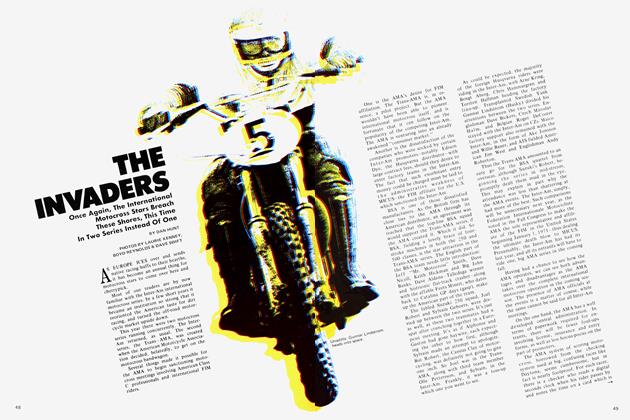

Most successful of the Husqvarna team members was Jeff Penton, who rated a Gold medal and had the fastest aggregate performance of all the riders in the special speed tests, which makes him overall winner of the Berkshire Two-Day. Not far behind him with Gold awards on Penton machines of half the displacement were two other members of the famous enduro riding Penton family, Tom and Jack. Father John Penton, the fourth member of the Husky team and a veteran ISDT rider, this time managed only a Silver.

In the Berkshire, much of the emphasis is on individual performance. Yet, like the ISDT, where European, Scandinavian and Iron Curtain motorcycle manufacturers participate heatedly and heavily for the prestige and reliability associated with winning this international event, the Berkshire has its share of official team competition, usually between American dealers and distributors, as well as club entries.

Trade team competition, which gives much life to any event, has come about only in the last few years, as a result of the broadening of the U.S. trail bike market. This is an extremely healthy trend for the consumer, as the battle for superiority between brands results in a certain amount of feedback to the factory through the American distributors. The trail bike buyer benefits as the manufacturers improve their machines to stay with the competition. However, in any highly contested type of event, a certain amount of specialization is needed, which will favor those manufacturers who are flexible enough (and usually small enough) to meet the challenge.

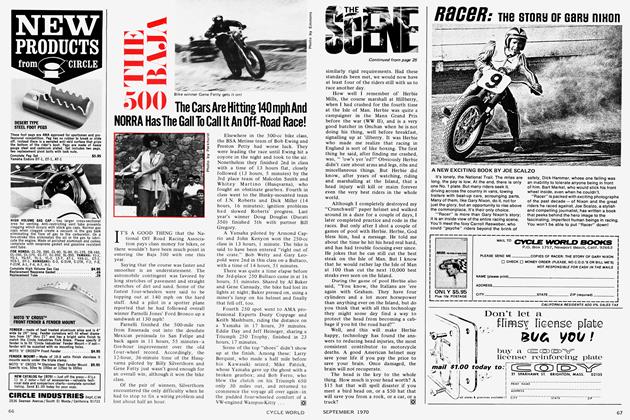

The only trade team to “zero” the trial was the Penton team, consisting of a quartet of 125-cc class two-strokes ridden by Leroy Winters, Doug Wilford, Jack Penton and Tom Penton. These remarkable machines, powered by the latest Sachs ISDT engines with gigantic radial fins, performed remarkably in the speed tests, equalling and sometimes beating competitively ridden machines of twice or three times the displacement. As such, this parallels the performance of similar super lightweight machines in European endurance runs; the lightweights used to be favored with slower schedules over there, but are now so fast that they hardly need the benefit of such a rule.

Bultaco made a massive effort in the Berkshire, entering two squads of well prepared Matadors, backed up by a motel full of gas check personnel and mechanics. Some of them backed up the trial organization itself and contributed greatly to the success of the event. The “B” team, composed of second-string riders, quickly faded. The “A” team held up well on time initially, but a series of those petty gremlin-type happenings— flat tires, stunning crashes, etc.—eroded away their overall performance. But “A” team rider Gerry Pacholke held his loss to 13 marks for a Silver, and teammates Bill Dutcher and Bob Maus won Bronzes with marks of 39 and 29 respectively.

The Yankee Motor Corp. team of Don Cutler, Charlie Vincent, Buck Walsworth and Bob Thompson, riding Ossa 250s, had mixed blessings. Cutler, Vincent and Walsworth zeroed the first day, but Bob Thompson was seriously injured in a high-speed crash, which smashed his ribs. Yankee chief John Taylor, running on zero time although not as a team member, retired to help get Thompson out of the hills to a hospital. Of the three left running, Cutler was the sole medalist, but it was a Gold with a special test score that ranked him 2nd in the 250 class. Team alternate Barry Higgins, the East Coast’s hottest property in 250-class motocross racing, won a Silver. Barry had been running zero time until a flat tire bogged him down in the very last section of the trial. His rim was spinning around but the back tire wouldn’t turn with it. So he ran out to the road, hustled up a piece of fence wire, strapped the tire to the rim, and continued on to the finish!

Of the Greeves entry, Chuck Boehler and Dave Latham won Gold medals, but the other two, John Trumbull and Bob Fisher, missed out on the awards. The Dalesman team produced a Silver and a Bronze. Neither of the two Yamaha teams garnered any awards.

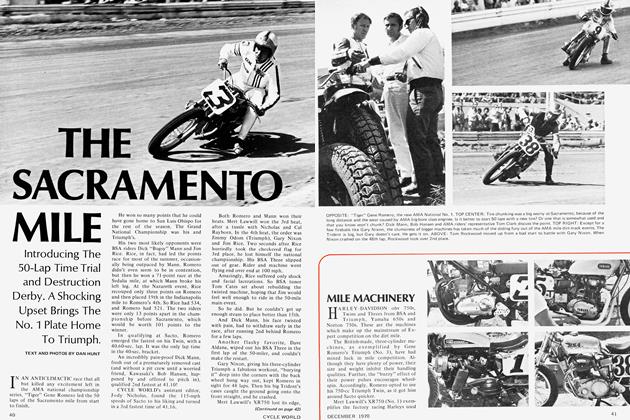

A Harley-Davidson entry of four Baja 100s read like a western star roster with riders Dave Ekins, Jack Krizman, Paul Hunt and Jonathan O’Neil. O’Neil quickly retired with a broken front wheel, while the other three machines didn’t seem to have either the luck or the steam to keep these riders within medal time. It is interesting to note the large number of flat tires that besieged many team and private entries on the first day. Many of these contestants figured that they could run extra low pressures, because of muddy conditions. However, this runs counter to European practice, where they run as much as 24 psi, presumably forsaking that last ounce of traction and more comfortable ride to prevent such trouble.

The Berkshire Two-Day, which may be expanded to three days next year, is fast becoming the premier enduro event in the United States. The terrain it covers is not impossible to get through (some Eastern riders would go bug-eyed at the sight of a Western downhill), nor is it intended to be. Not even the ISDT offers impassable sections. But where the Berkshire scores is in its resemblance to its European counterparts, its increasing professionalism, its avid support by the motorcycle trade and people of the region, and its impeccable organization. The usual enduro fare seems a little pallid by comparison.

1970 BERKSHIRE TRIAL RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

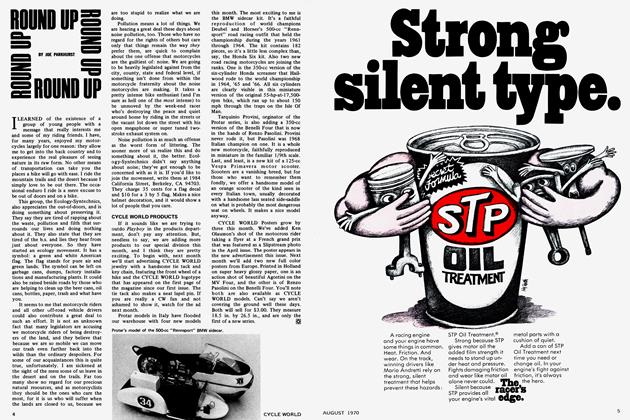

DepartmentsRound Up

August 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

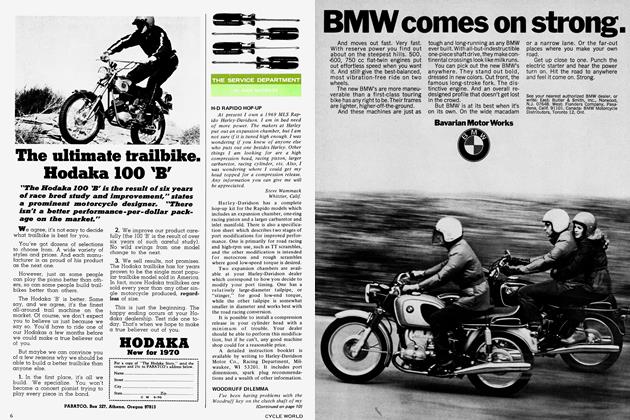

DepartmentsThe Service Department

August 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

August 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

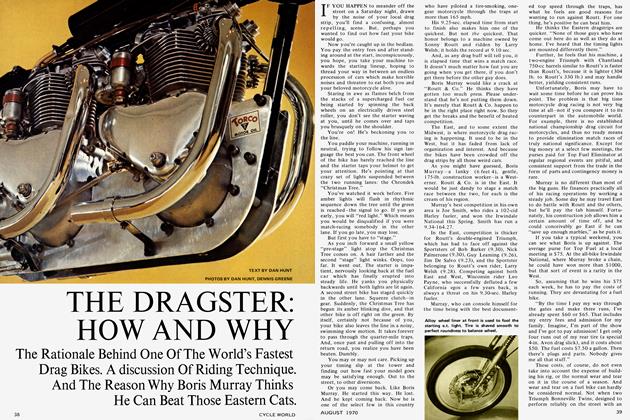

Special Features

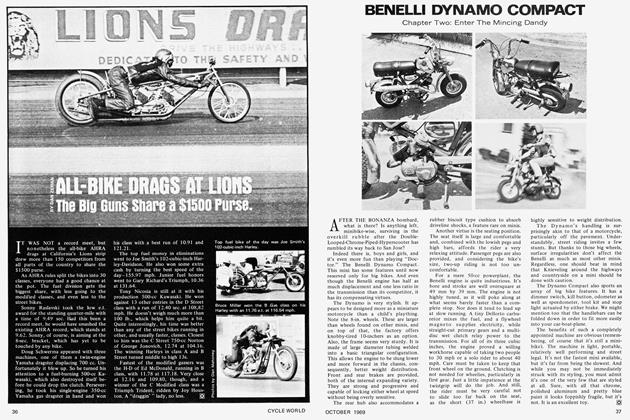

Special FeaturesThe Dragster: How And Why

August 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesThe Princess & the Peasant

August 1970 By Cecil P. Mack