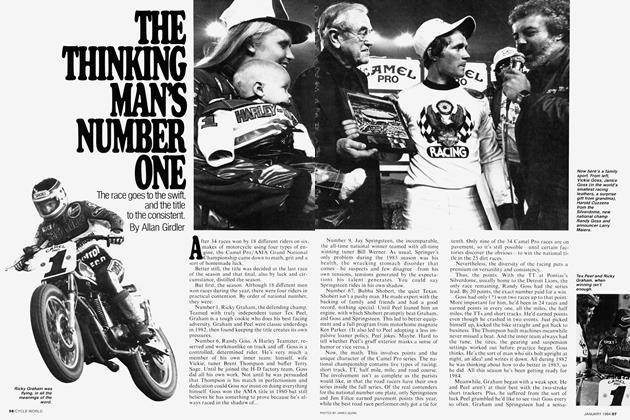

Ulster Grand Prix

Three Solo Riders Win Their First Grand Prix; Unrest in Belfast And Rain Hamper Promotion.

B.R. NICHOLLS

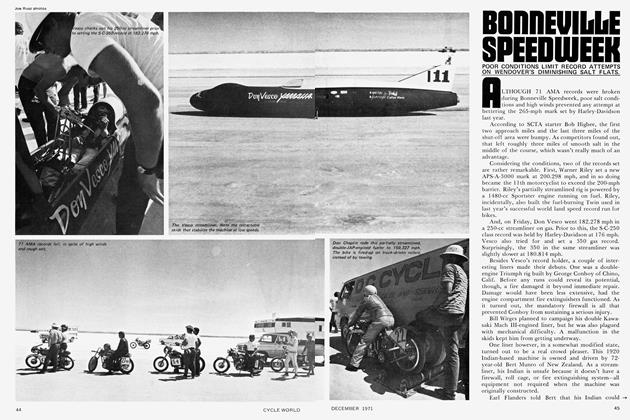

A WEEK BEFORE THE 1969 Ulster Grand Prix, civil unrest exploded into violence and the problem of Northern Ireland became world news. To the surprise of many, though, the 1969 meeting was held, and again last year the "Ulster" ran as usual. But the picture in 1971 was much more depressing, with bombings and shootings in Belfast a daily occurrence. Still the organizers clung like limpets to holding the races; had they cancelled, the financial loss would have been theirs. If the authorities banned the meeting, then compensation would have to be paid.

Race day dawned very wet, with little chance of any improvement. That brought a smile to Phil Read's face; he likes the wet and Rod Gould, his rival for the 250 title, does not.

The program was due to start with the 350 race, then the 250, but the clerk of the course suggested a switch, as the 250 race was expected to be the big race of the day. Read welcomed the idea; Gould did not. He wanted the 350 to get an idea of the conditions 'round the course. So racing did start with the 350 class, but for once Giacomo Agostini was missing from the line-up. Although his bikes had arrived in Belfast, he had not, and he was not the only one who had stayed away. Some sponsors were not prepared to risk men and machinery in that situation of unrest.

Favorite for the race was the flying Finn Jarno Saarinen (Yamaha), whose ability in the wet had already been proven. As the flag dropped the Italian Silvio Grasetti led the field on his 300-cc works MZ. He held it for three laps until the rain got the better of the electrics and Saarinen moved ahead. Saarinen had powered to a comfortable lead by the half-way stage when he loused his braking for the tricky hairpin corner and dropped it. The crowd really became excited because their local hero Tommy Robb (Yamaha) then moved to 1st, followed by Peter Williams (300 MZ). Then Robb pitted to cure a misfire, leaving Williams firmly in 1st place where he stayed to the end. Dieter Braun (Yamaha) was 2nd and Tony Jefferies (Yamsel), 3rd. Gould's idea of learning the conditions of the course ended abruptly on the fir£t lap; a stone dislodged the timing by some 30 degrees, effectively stopping the motor. Read went out after four laps when he had fought up to 2nd, so neither got a real feel of the circuit before the 250 race.

Read had uttered murmurs of discontent because he thought that Peter Williams' entry on the works MZ might upset the title battle going on between him and Gould, thinking that Williams would be a spoiler. He need not have worried. Williams made a bad start and managed no better than 4th by the finish. Read made a good start and left Gould way down the field at the end of the first lap. Gould did not improve much over the next few laps. By then Read had a fight on his hands when the Yamaha-mounted Irishman Ray McCullough forced the pace, despite Read's attempts to cool it. McCullough did not ease off, and so it went until the penultimate lap. By that time Read had resigned himself to 2nd place, as his engine lost its edge. Then the crankpin broke and with it all hope of that 2nd place. Second was taken over by Saarinen, almost Wi min. behind McCullough, with Braun 3rd on his Yamaha. Gould had circulated steadily in the final stages as the road dried and caught up to 6th place, which might just prove sufficient in the long run to retain his title for him.

After the lunch break the 500s lined up on the starting grid, and when the flag fell Jack Findlay streaked into the lead on his Suzuki. He was never headed. Behind him came the Dutchman Rob Bron, followed by New Zealander Keith Turner, making it a Suzuki 1-2-3. This was spoiled when Turner retired, and Robb (Seeley) took 3rd place.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 85

When the solo classes had finished, the realization came that each winner had never won a grand prix before. For Williams it was a big surprise. He had not even expected to ride the 300 MZ when he arrived at the meeting. For McCullough it was the dream story of local boy making good, and for Findlay it was a just reward for persevering for a decade on the continental circus, chasing elusive success.

During the 500 race the roads had dried completely, and as the sidecars started the last race of the day, the sun was breaking through. It was just what the BMW boys did not want in their battle against the lone Munch entry of Horst Owesle; wet roads would have made it difficult for Owesle to contend with the power of the four-cylinder Munch.

As it was, Owesle completely shattered the opposition with a start-to-finish victory, and lap and race records for good measure. Such was the chagrin of Arsenius Butscher that he protested, thinking the Munch was oversize. It was stripped and measured and found to be a fraction under 498cc. For Owesle it was the culmination of nearly 10 years' work with the power unit that resulted in the world title in only his second season of international racing. [Ö]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

DECEMBER 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

DECEMBER 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

DECEMBER 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesViewpoint: the Road Bike In Tomorrow's World

DECEMBER 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

CompetitionBonneville Speedweek

DECEMBER 1971