REPORT FROM JAPAN

YUKIO KURODA

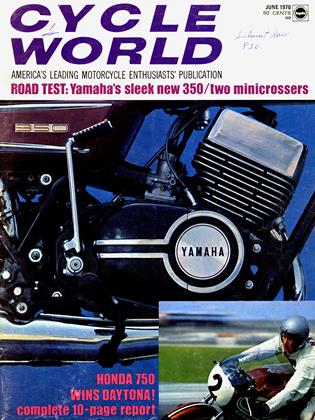

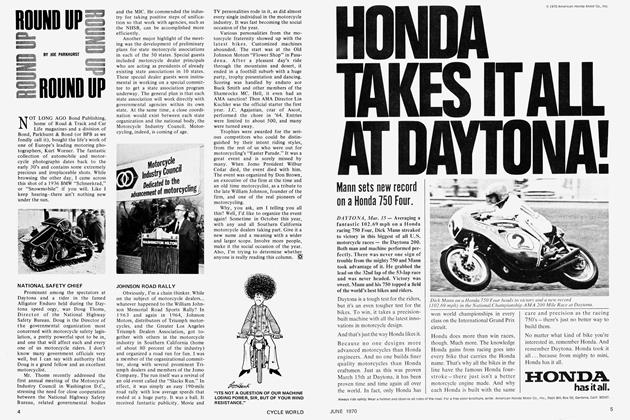

HONDA WINS DAYTONA

After years of disinterest in the American racing scene, Honda sharpened and polished up a few of their four-cylinder 750 engines, wound chrome-moly frames around them, doubled up the discs for hot road race braking, and put them on the airplane for the USA. And promptly won what has become the most important road race in the world.

I talked about the racing 750 with Mr. H. Sekiguchi, chief of Honda’s Research and Development Co., at the well-guarded center in Saitama Prefecture, outside Tokyo. Like others at Honda, he took the big win in stride, even though Honda could not really have been expected to win Daytona, having never run the AMA event there before (the last time Honda showed up was in the early 1960s, when the nowdead USMC ran the U.S. Grand Prix events there). After building grand prix machinery for more than 10 years, and winning scores of world championships with every size of bike from 50 to 500 cc, Honda’s confidence and lack of surprise are understandable.

The factory 750-cc racers weren’t even ridden in Japan—that was only partly a result of Honda’s confidence, though, for the time factor was critical in the preparation and entry of the big racers. While the Japanese firm may have decided to run the 200-miler just after the rules change last autumn to include 750 cc, other pressing work at the R & D Co. prevented them from preparing the machines until recently... and there was no time to test-ride it in Japan.

Engine preparation was along fairly conventional Unes, with no use of titanium or other exotic materials. Still, plenty of careful thought was necessary to squeeze the big Four enough to make it wail, and to get the 500-lb.-plus road design down to a raceable weight of. . . 375 lb. sound believable to you? That’s no more than a lot of production racing machines, and less than some, so it wouldn’t take a Primo Camera to wrestle it around corners—though Dick Mann apparently was concerned about the weight when he was first approached about riding the Four.

If the factory can get the horsepower, it can usually get the weight and handling—if it tries hard enough for a good balance. The latest version of the 350-cc racer, that Honda’s Racing Service Club has built out of a road 350, only weighs 220 lb. That’s a figure somewhat below the magic 240 lb. that Honda road racers drilled and whittled to get their machines down to years back. Of course they didn’t have goodies like titanium fork sliders and engine bits, magnesium engine cases, etc. The CB350 racer is getting around Suzuka about as fast as an early fourcylinder 350, which shows how rapidly the technology is advancing.

Speaking of magnesium engine parts, according to one rumor I picked up, all Honda motorcycle and car engines will employ magnesium/aluminum alloy engine cases in the near future; apparently Honda has worked out some new casting process that should make magnesium feasible for mass production—and the considerable weight-saving achieved should help dispel that heavy Honda image.

ROTARY ENGINE FOR BIKES?

No, I don’t think so. But the entry of Toyo Kogyo’s newest rotary-powered Mazda mini-sedan, a single-rotor 360-cc wonder that aims to carve out a nice portion of the “kejidoosha” (minisedan) market, revives speculation that this engine will appear someday in motorcycles.

The engine was developed from the two-rotor, 500-cc (X 2) displacement mill which powers larger rotary sedans. As one rotor would still displace 500 cc, it was simply slimmed to meet the legal limit of 360 cc for this class vehicle. While the engine is tuned for 36 bhp, Toyo Kogyo engineers admit that much more power is easily available from the compact, well-balanced engine...and its light weight and lack of reciprocating forces would give new freedom to frame design, conceivably resulting in less weight and great handling.

Are you listening, Bridgestone?

KAWASAKI BACKING SIMMONDS

Sort of, anyway. The big Japanese aircraft/ship/train/motorcycle maker had hoped to show smoke to the competition at Daytona with their racing H-1R (and they did in the Amateur 100-miler) but apparently the 50 percent displacement handicap was too much for them in the Expert event. Kawasaki will be trying hard to win in other important AMA and AFM events this year in the United States, but it will take some spectacular winning of big European events by road racer Dave Simmonds to make up for the loss at Daytona.

Simmonds, who won the 125-cc world championship on an elderly but quick twin-cylinder machine in 1969, has been given a spanking new H-l R and another ex-works 125-cc machine to compete on in 1970. He doesn’t have any fat money contract, though, as he might have had in the golden days of Japanese participation in European road racing; he’ll have to hustle bread out of organizers and engage in other such hens’ teeth pulling operations to make a living on the bikes. Kawasaki never was very deeply committed to European GP racing, believing that wins there wouldn’t be as good for sales in the important American market as victories in American events. Still, its machines are fast enough to do the job in Europe, and it would be no surprise if Dave, whom many American riders probably remember as one of the friendlier British riders, comes up with another world championship for Kawasaki in 1970. Maybe even two.

Best of luck to Dave and Kawasaki in the new racing season.

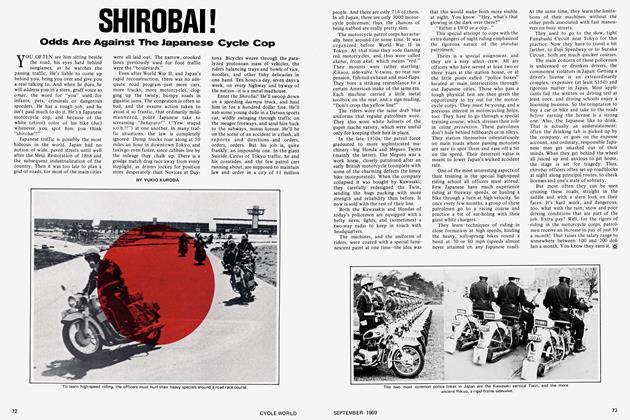

COMMANDO CATCHING ON

The Norton 750-cc Commando is catching on, which is quite a switch, really, what with Japanese makers owning about three-quarters of the British market these days. But Japanese riders have become much more sophisticated in recent years, and many have become interested in the fine styling and legendary handling of big British roadburners. There are a number of Triumph Bonnevilles, and even an occasional BSA Rocket Three, running around Tokyo.

But the bike, which has caught the imagination of young Japanese riders more than any other import, is the Norton Commando. And I can understand why, having ridden a Commando over 4000 miles from London to Tehran last year with no spills and no trouble for the whole race, I mean trip, I mean journey. I was naturally interested in finding out what sort of Norton dealer was introducing Japanese riders to this famous old marque, so I paid a visit to Murayama Motors, one of the most important foreign motorcycle dealers in the Tokyo area.

Mr. Murayama’s father started the business 45 years ago, dealing in Harleys, Indians, Rudges, New Imperials, NSUs, BSAs, Nortons, and even indigenous Japanese makes like Rikuo and Asahi. It is the oldest dealership in Japan, and still one of the largest—over 100 machines are sold every year. Most are Triumphs and Nortons, though some Japanese, rich ones that is, still go in for more exotic stuff. When I saw a huge Electra-Glide in full dress waiting to be picked up, I just about flipped. It seems it was for a millionaire real estate agent on the Ginza who drives a Rolls Royce and dabbles in all sorts of expensive toys like yachts and Mercedes. And at over $4000, including the steep import duty, the Harley 74 is a plenty expensive play-pretty.

“Triumph” in Japanese is pronounced “toraiampuhu,” but the mechanics around the Murayama shop just say “tora,” which is the word for “tiger” in Japanese. There are five mechanics at Murayama, helping to fix street racing Dominators that have bent some of the scenery or been run out of revs. One of the tuners, a Mr. Sekiguchi, says he would like very much to come to the U.S. and work on Triumphs and Nortons for an American dealer. If any of you know of a British machine dealer who’d like to have a tiptop Japanese mechanic, drop me a line in care of CYCLE WORLD and I’ll get it to Sekiguchi-san.

(Continued on page 110)

One of Mr. Murayama’s customers is a gent named Kurihama, who runs a Norton in professional speedway racing, where pari-mutuel betting keeps things lively (I hope to have an article on this interesting but dangerous profession in a future issue of CYCLE WORLD). Mr. Murayama himself is a member of, and rides with, the Tokyo Trials Club, whose 100 members make long-distance tours together as well as organizing trials events.

One of Mr. Murayama’s best-known customers—and one of his oldest—is a Mr. Morio, a paper dealer in downtown Tokyo, who rides a faired Norton Commando with modified pipes and Triumph mufflers for fast cornering. He rides in full leathers, and looks like the ton-up boys you see burning up the roads in Jolly Olde. The machine is also equipped with a Japanese-made electric heater, which keeps hands, knees and bottom warm during freezing winter rides. When Mr. Morio told me he had ridden many bikes before the Commando and listed a BMW, BSA, Triumph, Harley, Rikuo, Asahi and Captain among others, I began to get a little suspicious. “How old are you?” I asked him. He smiled and said “Fifty” which is about 20 more than I had thought. All of which proves there’s nothing better than a fast bike to keep you young—if you can avoid the chugholes and little old ladies in Hudsons.

HONDA’S NEW US90

What is it? Well, you’ll have to decide for yourself. It has handlebars and controls, and an easily recognizable S90 engine, but apart from that it looks like a tricycle with a berserk thyroid.

It climbs stairs. And it drives through snow and across mud and ice. And it wallows through sand like a dune buggy. I guess you’d have to classify it as an ATV—all terrain vehicle. Honda just calls it the US90, and said that U.S. dealers were impressed when they saw a prototype during a visit to Japan last autumn.

It was developed especially for the export market, and that’s a good thing because the Japanese government refused to allow it to be sold in Japan, saying it wouldn’t be safe enough without a differential.

The engine is equipped with a threeby two-speed transmission, giving ratios for fast riding (like up to 25 mph) and ultra-low ratios for rooting through mudholes (though I wonder if the 90 has the power to pull it out of a good slushy all-American mudhole).

The tires are filled to about a 4-lb. pressure, which means you should be able to blow them up with a couple of lungfuls of air (if you dare breathe that much at one time). The machine has a climbing ability of 30 degrees and will navigate up stairways, in case you live on the 11th floor and the elevator’s on strike. The US90 breaks down into six pieces for carrying in your car, too.

It even walks on water, having enough buoyancy to support itself in deep spots—though if you want to ride it across a river you had better be prepared to dog-paddle.

Inasmuch as it is of a tricycle design, and doesn’t bank into turns, it requires a rather special riding technique. I’d advise you to consult with a three-yearold child on how to sling your body on the inside of a turn when changing directions quickly (though you can forget about the pedaling).

Race technique (yes, they’ve already begun to ride them to the limits) requires that you bank on two wheels, but sidehack artists can get that in a minute. One of the most fun things on the US90 is doing doughnuts, as its turning radius is about zero and you can switch ends before you know it. They also jump and do wheelies, sort of...in short, here is one all-around fun vehicle. I’ll be waiting to see what sort of devious joys American riders can get out of these cute little devils once they hit the States.

This will be soon, as the giant Suzuka factory, working only part capacity foi some time now, will be tooling off US90s as quick as you can run over your own foot and not even feel it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumIllinois Success Story

JUNE 1970 By Lee Strobel -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Competition Feature

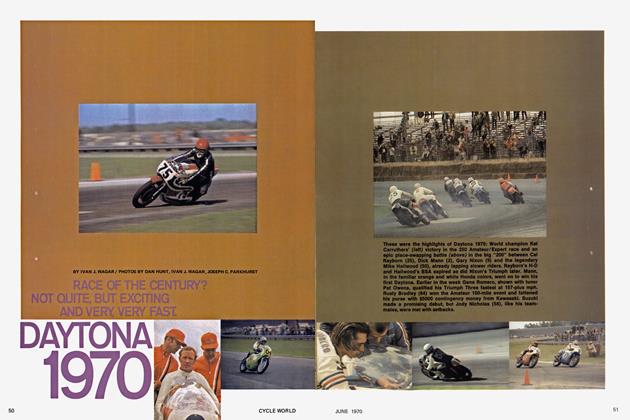

Special Competition FeatureDaytona 1970

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

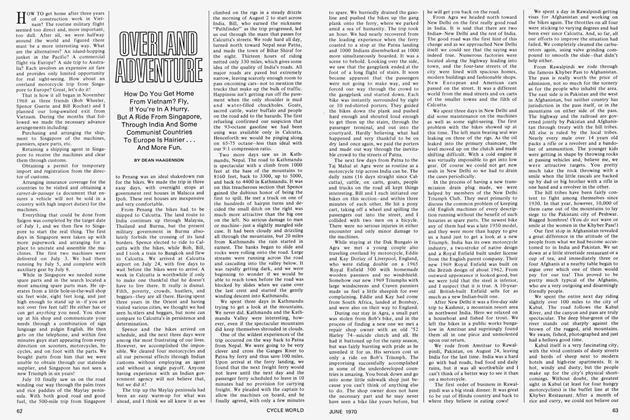

FeaturesOverland Adventure

JUNE 1970 By Dean Haagenson