REPORT FROM JAPAN

YASUO YOSHIHARA

YUKIO KURODA

DOMESTIC BIG BORE BOOM

There is a mild resurgence in the popularity of big motorcycles in Japan these days; while domestic sales have leveled off to about 600,000 a year (having peaked out at 720,000 in 1967), the number of 350-cc and bigger displacement machines is steadily increasing: 12,800 in 1967, 18,000 in 1968 and 20,000 in 1969. At the present there is a taste for high-horsepower machinery in Japan, more than ever before; this has apparently been one of their many blessings from the West. While a Japanese rider of the 1950s was thankful if he could afford motorized transportation of any sort, and double happy if he ended up with a new machine, after the magic of small machines wore off and the income of the average wage-earner started to climb higher and higher, people tended to want to move up to wheels that went harder, looked fancier and, naturally, cost more (the same is true for the Japanese car industry).

How’s it grab you that a small shop owner who might need a little motorbike to run errands around Tokyo might go out and buy a new four-cylinder Honda 750? Or a big eat ’em up Kawasaki 40-incher W2SS? That’s exactly what’s happening. Although these machines may cost as much or more than many new passenger cars (the small 360-cc versions) they are doing very well on the local market-and 250s and 350s are also enjoying more popularity than ever before among high school students, young businessmen and others. Kawasaki has stopped exporting their 650-cc machine to the United States (as mentioned in last month’s report). While they may indeed have something else up their sleeve (more on that later) one of the main reasons is that the long-stroke parallel Twin is selling like strawberry-flavored joints at a love-in, right here at home in Japan. And this healthy domestic market for big machinery-specifically for tough, brutish, Iron Man 650-750-cc mounts— is one reason why Yamaha has introduced their new XS 1-650. They’d like to horn in a little on the good domestic sales; they’re also hoping to make a dent in the ever-widening export market (for example, the very plump police bike market-Kawasaki has just sold a batch of their police models to Korea, Australia and South Africa). 1 got the background and some sales philosophy on the big machine when I visited the Yamaha Motor Co. in the coastal city of Hamamatsu recently.

This city is just about midway between Tokyo and Osaka, the two centers of commerce in Japan, and is famous for the many industries located there. Suzuki has several factories in the area, and not too far from the huge Yamaha works there is a Honda factory where they’re tooling out 3000 of the four-cylinder models every month for you and me to win speeding tickets on.

I arrived after a 125-mph wail down the Tokaido Line on Japan’s bullet express; soon I was sitting face to face with the folks from Yahama, trying to pry loose some news from them.

I didn’t learn much—there wasn’t much news around Yamaha now that they’ve unveiled their new models for 1970. But 1 did pick up some information about the 650—a new XS 1-650 was to be air-mailed to CYCLE WORLD in Long Beach for an ultra-early road test two days after I was at the factory.

INSIDE SCOOP ON XS1 YAMMY . . .

Everybody was a little startled when the 650 was first announced, at the 1968 Tokyo Motor Show. Yamaha had been singing the praises of the two-cycle engine from the Year 1, and here they were with a four-stroke model at the head of their line. The truth is that they initially planned and built a twin-cylinder 650-cc two-stroke prototype; it was air cooled, according to the company, though I’ve also heard rumors that there was a water-cooled version about. Yamaha found that the optimum horsepower output from this sort of engine would be around 53 bhp-the same as the new XS 1-650 is said to develop. The two-stroke machine drank too heavily and sounded like a drowning rhinoceros (they didn’t put it in those terms but I think that’s what they meant), and after close consultation with people at Yamaha International the company decided to build a four-stroke.

Two full years were spent on designing and testing and getting a production line set up for this machine it must be one of the most thoroughly-tested and worried-over machines ever built. From all impressions, though, 1 suspect that there was a good deal of indecision and fretting about the plunge into the bigbike market before the machine was actually given the go-ahead.

In plumping for a four-stroke, Yamaha followed the lead of other companies who augment a small-displacement twostroke line with a big four-cycle touring machine: Kawasaki and American Fagle, for example. But while Yamaha sat and wondered if they should go ahead with the rather conventional Twin, Honda, Kawasaki, BSA and Triumph came along and did it to them with neat multi-cylindered models. Yamaha is still convinced they can sell the machine to a certain category of rider who doesn’t like big two-strokes or multis; they have done market research on the subject.

Initially, 500 XSl-650s will be built a month; and from May of 1970 monthly production will go GABAT! (as they say in Japanese comic strips) and soar up to a thousand.

...THE 350 SINGLE...

The Yamaha RT-1 scrambler (and the RT-1M motocross version) is being tested in the C’alifornia desert as of this writing, and once details are worked out the machine should start coming off the production line-about the same time as the 650, say January of 1970. Happy new year, Yamaha!

I got to snoop through the Yamaha factory when I visited Hamamatsu; they even had a handful of 650s on the production line. But they wouldn’t let me ride one of these still ultra-new street machines, so I couldn’t report to you if Yamaha has solved the annoying vibration problems that give English 650s such fits (same type of engineparallel Twin and all that you know).

...AND EVEN THE RACERS!

A little further down the line I saw what must be one of Japan’s tiniest production linesthree people carefully hand-assembling a batch of TD-2 and TR-2 Daytona road racers that looked clean and beautiful and fresh enough to eat. All assembly on these machines, including such things as port finishing, is done by hand, and one of the workers sewing up the 150-mph racers was a sweet-faced middle-aged lady who looks like my Aunt Hattie who used to teach Sunday School. When Yoshihara-san said, “Cheese,” she gave a toothy smile and he snapped the picture you see here. I asked her for the lowdown on a rumored model change to a “TD-3” in 1970, and she said there would be no major changes except for the addition of a crocheted doily on the racing tank, lace curtains on the windscreen and a molded fiberglass handbag (integral with the fairing) for lady racers to carry their lipstick and makeup in when they race.

(Continued on page 80)

Yamaha only hand-knits 30 of these machines a month for racers around the world (they won’t sell them domestically to Japanese road racers, which seems like a pretty bad idea to me), and the machines are ordered up for the next year in advance. Of the 300 or so units made a year, a little over a hundred go to the U.S. and the rest are sent to Europe and (occasionally) to far-off places like Austalia and Southeast Asia. It costs the company a lot of trouble and money to build these machines, for they are a pain to producehand-made components, hand assembly, plus genuine road-race type high-speed test runs around Yamaha’s beautiful test track. If a test rider doesn’t turn a sufficiently quick time on the machine, it is sent back to be checked over. Wouldn’t it be nice if they could road test street machines that way: “I hate to bother you, but your brochure lists the top speed of my Norimaki 120 as 143 mph and it will only do 140. Send it back to the race division to be looked after, would you please?”

THE HONDA RSC’S STILL AT IT

Speaking of racing, how would you like to see something really beautiful? Just look at this lovely little item from the Honda Research and Development Company. No, it’s not a rare piece off a GP bike-it’s too big for that.

The legendary days of GP Hondas are gone forever. But now that the company has smiled politely and excused themselves from GP racing, they can afford to devote more time to building research/racing goodies like this piston -tested and sold through the Racing Service Club, a Honda subsidiary located at Suzuka Circuit. This masterpiece of Speed Art only weighs 150 grams; it has eggshell-thin walls and dome, and it is designed to help the Honda CB350 racer run like a bird out of heaven, stoking over 50 bhp at 1 1,500 rpm. It looks more fragile than the usual sturdy Honda component, but you would naturally want to strip your engine and swap pistons after every race, wouldn’t you?

Don’t go knocking on American Honda’s door if you should happen to want a set of these, though. Nice People don’t dig the racing image...

WE ALL LOVE RUMORS

Everybody fibs or tells whoppers or invents good stories once in a while, but automotive journalism is extraordinarily subject to this type of reportage, when it comes to new models that haven’t been announced yet. 1 call it The Judge Crater Complex. “If there isn’t any news, well then invent some” (this is a peculiar affliction of English motor journalism-war-size headlines screaming “Will Honda Come Back to GP Racing??” followed by reams of six-point type detailing past history and rumors, and ending with “No, but we sure wish they would.”)

Now that I’ve warned you, set you up as it were, I’ll tell you about a little fowl I know. I was walking around one day minding my own business (as much as I ever do, anyway) when what should I spy with my spyglasses but this little birdie, astride a huge monster.

I sauntered over and said, “Hello, little birdie!” and he replied, “Hiya chum!” and I said, “Say, that looks just like a giant Suzuki you’re riding there!” and he scowled and clenched his teeth and said, “Is that a fact, buster? Well look again!” When I blinked and looked again he was gone, in a huge thundercloud of blue smoke; coughing, I followed his trail of burnt rubber down the road a piece but then it vanished into the sky-I guess he launched off for the moon. I didn’t get much of a chance to look at the machine but it did have an awful lot of cylinders on it-not as many as the biggest Honda, I don’t think, but lots more than the Suzuki 500. And it went rung-a-dung, sort of, and looked as though it had many many cc’s stuffed in its cheeks. If I see it again I’ll be sure to send a hot flash to CYCLE WORLD, to give you a rundown on the machine (assuming it’s for production, for any old company can build an exotic test machine and run it around a race course while spies and photo-journalists shiver in trenches and snap pictures with long lenses—they might even do it just to scare hell out of the competition).

And then there is the mysterious Kawasaki Kaper. I have a big hunch they’re up to something; they usually are, as you can tell by looking at the panoply of surprises they’ve come forth with over the years: the first twin-cylinder rotary valve machines, the first Three, the first with capacitor discharge ignition...now what?

I don’t know. But we can use our powers of deduction to give it a good guesss. Let us briefly study the situation: 1) Kawasaki has always fielded a complete line of bikes, ranging in size from 50 cc to 650 cc. 2) Now they have stopped exporting the big Twin W2SS to the U.S.-it is selling well in Japan and in other places, but it couldn’t do a thing against the competition from other big four-strokes. 3) Kawasaki knows there is a big-bike market in the USA, and that it’s getting bigger, and there is no doubt in my mind that they have no moral objections to grabbing hold and ripping off a chunk of it for themselves. 4) They’ll have to build something fantastic, to outdo Honda, etc. 5) If they do come out with a new model, they’ll probably stick with a four-stroke design, since they appear convinced that’s the best way to compete with the big bikes (though a factory engineer told me several years ago that Kawasaki wasn’t especially anxious to compete with Honda in the four-stroke field-after all, who could compete with Honda?).

So what are they up to? No one knows, but from the above we can sit by the fireplace, warming our hands as the snows rage outside, and think about it. One thing is certain: it won’t be a doctored Mach III—this machine can only be bored out to around 550 cc before you strike sunlight, and it won’t go very quick with those kinds of ports in it. We’ll mull this one over for awhile, and I’ll let you know if anything develops on this end.

That’s all the news from picturesque Japan. The trees are turning golden and brown, and it’s getting too chilly to ride much these days. The other day I was sitting in a coffee shop, warming up after a long, cold ride, and who should walk in but an old buddy from years ago? We sat around shooting the-ah, time of day and he told me he saw somebody running an incredible overhead-camshaft V-Four 900-cc machine at the Yatabe test track just the week before. And as soon as he asked who the machine belonged to, they loaded it up in a big truck with “Kawasaki” painted on the side and lit out.

But I don’t know if I believed him or not-hell, the world’s just full of crazy people!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

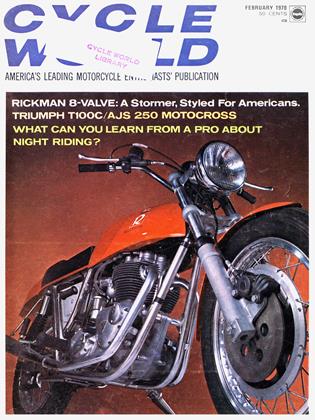

February 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1970 -

Features

FeaturesNight Rider

February 1970 By Stuart Munro -

Features

FeaturesHow To Teach Your Girl To Ride

February 1970 By David C. Hon -

Special Color Feature

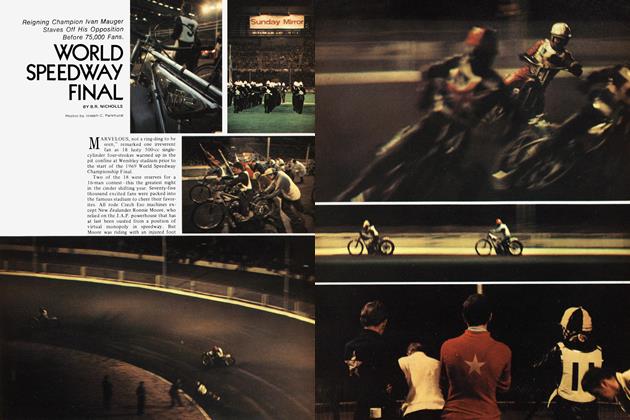

Special Color FeatureWorld Speedway Final

February 1970 By B.R. Nicholls