OVERLAND ADVENTURE

How Do You Get Home From Vietnam? Fly, If You're In A Hurry. But A Ride From Singapore, Through India And Some Communist Countries To Europe Is Hairier... And More Fun.

DEAN HAAGENSON

HOW TO get home after three years of construction work in Vietnam? The routine military flight seemed too direct and, more important, too dull. After all, we were halfway around the world and figured there must be a more interesting way. What are the alternatives? An island-hopping junket in the Pacific? A commercial flight via Europe? A side trip to Australia? Each involves an expensive air fare and provides only limited opportunity for real sight-seeing. How about an overland motorcycle trip from Singapore to Europe? Great, let's do it!

That is how it all began in November 1968 as three friends (Bob Wheeler, Spence Guerin and Bill Rochat) and I planned our long-awaited exit from Vietnam. During the months that fol lowed we made the necessary advance arrangements including:

Purchasing and arranging the ship ment to Singapore of the machines, panniers, spare parts, etc.

Retaining a shipping agent in Singa pore to receive the machines and clear them through customs.

Obtaining a permit for temporary import and registration from the direc tor of customs.

Arranging insurance coverage for the countries to be visited and obtaining a carnet-de-passage (a document that en sures a vehicle will not be sold in a country with high import duties) for the machines.

Everything that could be done from Saigon was completed by the target date of July 1, and we then flew to Singa pore to start the real thing. The first days in Singapore were taken up with more paperwork and arranging for a place to uncrate and assemble the ma chines. The first two machines were delivered on July 3. We had them running by July 5, and complete with auxiliary gear by July 8.

While in Singapore we needed some spare parts and in the search located a most amazing spare parts man. He op erates from a little hole-in-the-wall shop six feet wide, eight feet long, and just high enough to stand up in-if you are not over five feet tall! He either has or can get anything you need. You show up at his shop and communicate your needs through a combination of sign language and pidgin English. He then gets on the telephone, and within five minutes guys start appearing from every direction on scooters, motorcycles, bi cycles, and on foot with the parts. We bought parts from him that we were unable to obtain through our stateside supplier, and Singapore has not seen a new Triumph in six years!

July 10 finally saw us on the road winding our way through the palm trees and rice paddies of the Maylay penin sula. With both good road and good fuel, the 500-mile trip from Singapore to Penang was an ideal shakedown run for the bikes. We made the trip in three easy days, with overnight stops at government rest houses in Malacca and Ipoh. These rest houses are inexpensive and very comfortable.

From Penang the bikes had to be shipped to Calcutta. The land route to India continues up through Malaysia, Thailand and Burma, but the present military, government in Burma abso lutely forbids the crossing of its land borders. Spence elected to ride to Cal cutta with the bikes, while Bob, Bill, and I took a train to Bangkok and flew to Calcutta. We arrived at Calcutta airport on July 24, with five days to wait before the bikes were to arrive. A week in Calcutta is worthwhile if only to make one thankful that he doesn't have to live there. It really is dismal. Filth, poverty, crowds, hustlers, and beggars-they are all there. Having spent three years in the Orient and having visited various cities, we thought we had seen hLstlers and beggars, but none can compare to Calcutta's in persistence and determination.

Spence and the bikes arrived on schedule, and the next three days were among the most frustrating of our lives. However, we accomplished the impos sible. We cleared four motorcycles and all our personal effects through Indian customs without employing an agent and without a single payoff. Anyone having experience with an Indian gov ernment agency will not believe that, but we did it!

The trip up the Maylay peninsula had been an easy warm-up for what was ahead, and I think we all knew it as we climbed on the rigs in a steady drizzle the morning of August 2 to start across India. Bill, who earned the nickname "Pathfinder" as the trip progressed, led us out through the maze that passes for Calcutta's streets. We rode hard all day, turned north toward Nepal near Patna, and made the town of Bihar Shiraf for the night. Thirteen hours of riding netted only 330 miles, which gives some idea of the quality of India's roads. All major roads are paved but extremely narrow, leaving scarcely enough room to pass oncoming cars-not to mention the trucks that make up the bulk of traffic. Happiness isn't getting run off the pave ment when the only shoulder is mud and water-filled chuckholes. Goats, sacred cattle, water buffalo and people on the road add to the hazards. The first refueling confirmed our suspicion that the 93-octane gasoline we had been using was available only in Calcutta. Henceforth we would be pinging along on 65-75 octane-less than ideal with our 9: 1 compression ratio.

Two more days saw us in Kath mandu, Nepal. The road to Kathmandu is spectacular with a climb from 1000 feet at the base of the mountains to 8160 feet, back to 3300, up to 5000, and back to 4400 in Kathmandu. It was on this treacherous section that Spence gained the dubious honor of being the first to spill. He met a truck on one of the hundreds of hairpin turns and de cided the small ditch on the right was much more attractive than the big one on the left. No serious damage to man or machine-just a slightly mangled side case. It had been cloudy and drizzling all through the mountains, but 20 miles from Kathmandu the rain started in earnest. The banks began to slide and rocks were rolling onto the road. Large streams were running across the road and cascading into the valley below. It was rapidly getting dark, and we were beginning to wonder if we would be able to reach town before the road was blocked by slides when we came over the last crest and started the gently winding descent into Kathmandu.

We spent three days in Kathmandu trying to get a look at the mountains. We never did. Kathmandu and the Kath mandu Valley were interesting, how ever, even if the spectacular mountains did keep themselves shrouded in clouds.

One of the wildest experiences of the trip occurred on the way back to Patna from Nepal. We were going to be very clever and cross the Ganges River to Patna by ferry and thus saveS 100 miles. Upon arrival at the ferry landing, we found that the next freight ferry would not leave until the next day and the passenger ferry scheduled to leave in 10 minutes had no provision for carrying freight. We pleaded with the captain to allow the machines on board, and he finally agreed, with only a few minutes to spare. We hurriedly drained the gasoline and pushed the bikes up the gang plank onto the ferry, where we parked amid a sea of humanity. The trip took an hour. We had nearly recovered from the loading experience when the ferry coasted to a stop at the Patna landing and 1000 Indians disembarked as 1000 more simultaneously boarded. It was a scene to behold. Looking over the side, we saw that the gangplank ended at the foot of a long flight of stairs. It soon became apparent that the passengers were not going to make way, and we forced our way through the crowd to the gangplank and started down. Each bike was instantly surrounded by eight or 10 red-shirted porters. They guided the bikes down the plank and pushed hard enough and shouted loud enough to get them up the stairs, through the passenger terminal, and out into the courtyard. Hardly believing what had happened and very thankful to be on dry land once again, we paid the porters and made our way through the inevitable crowd to the streets of Patna.

The next few days from Patna to the Taj Mahal at Agra were as routine as a motorcycle trip across India can be. The daily rains (16 days straight since Calcutta), cattle, ox carts, goats, people and trucks on the road all kept things interesting. Bill and I each initiated our bikes on this section—and within three minutes of each other. He hit a pony cart, taking off a wheel and spilling the passengers out into the street, and I collided with two men on a bicycle. There were no serious injuries in either encounter and only minor damage to the machines.

While staying at the Dak Búngalo in Agra we met a young couple also traveling overland by motorcycle, Eddie and Kay Doriay of Liverpool, England, who were riding double on a 1965 Royal Enfield 500 with homemade wooden panniers and no windshield. Somehow our new 1969 Triumphs with large windscreens and Craven panniers made us feel a little sheepish for ever complaining. Eddie and Kay had come from South Africa, landed at Bombay, and were also on their way to England.

During our stay in Agra, a small part was stolen from Bob’s bike, and in the process of finding a new one we met a repair shop owner with an old ’52 Harley 74—suicide clutch and all. He had it buttoned up for the rainy season, but was fairly bursting with pride as he unveiled it for us. His services cost us only a ride on Bob’s Triumph. The improvising successfully accomplished in some of the underdeveloped countries is amazing. You break down and go into some little sidewalk shop just because you can’t think of anything else to do. The shop owner does not have the necessary part and he may never have seen a bike like yours before, but he will get you back on the road.

From Agra we headed north toward New Delhi on the first really good road in India. It is said that there are two Indias^-New Delhi and the rest of India. The good road was the first hint of this change and as we approached New Delhi itself we could see that the saying was indeed true. Numerous factories were located along the highway leading into town, and the four-lane streets of the city were lined with spacious homes, modern buildings and fashionable shops. New European and American cars passed on the street. It was a different world from the mud streets and ox carts of the smaller towns and the filth of Calcutta.

We spent three days in New Delhi and did some maintenance on the machines as well as some sight-seeing. The first problem with the bikes showed up at this time. The left main bearing seal was leaking on three of the rigs. As the oil leaked into the primary chaincase, the level moved up on the clutch and made shifting difficult. With a cold engine it was virtually impossible to get into low gear. Of course we could not get new seals in New Delhi so we had to drain the cases periodically.

In the process of having a new transmission drain plug made, we were helped by members of the New Delhi Triumph Club. They meet primarily to discuss the common problem of keeping old English machines of every description running without the benefit of such luxuries as spare parts. The newest bike any of them had was a late 1950 model, and they were more than happy to give us a hand just to get a look at a new Triumph. India has its own motorcycle industry, a two-stroke of native design and a Royal Enfield built under license from the English parent company. Their new 1969 Royal Enfield was built on the British design of about 1962. From outward appearance it looked good, but we were told that the steel is inferior, and I suspect that it is true. A 10-yearold British-built Enfield sells for as much as a new Indian-built one.

After New Delhi it was a five-day side trip to Kashmir, a mountain resort area in northwest India. Here we relaxed on a houseboat and fished for trout. We left the bikes in a public works bungalow in Amritsar and suprisingly found them all in one piece and unmolested upon our return.

We rode from Amritsar to Rawalpindi, Pakistan, on August 24, leaving India for the last time. India was a hard go with bad roads, bad food and daily rains, but it was all worthwhile and I can’t think of a better way to see it than on a motorcycle.

The first order of business in Rawalpindi was a big steak dinner. It was great to be out of Hindu country and back to where they believe in eating cows!

We spent a day in Rawalpindi getting visas for Afghanistan and working on the bikes again. The throttles on all four were sticking to varying degrees and had been ever since Calcutta. And, so far, all our efforts to improve the situation had failed. We completely cleaned the carburetors again, using valve grinding compound to smooth the slide—that didn’t help either.

From Rawalpindi we rode through the famous Khyber Pass to Afghanistan. The pass is really worth the price of admission, not so much for the scenery as for the people who inhabit the area. The east side is in Pakistan and the west in Afghanistan, but neither country has jurisdiction in the pass itself, or in the mountains on either side of the pass. The highway and the railroad are governed jointly by Pakistan and Afghanistan through treaty with the hill tribes. All else is ruled by the local tribes. Nearly every male over 14 years old packs a rifle or a revolver and a bandolier of ammunition. The younger kids were getting in shape by throwing rocks at passing vehicles and, believe me, we were attractive targets. You pretty much take the rock throwing with a smile when the little rascals are backed up by dad or big brother with a rifle in one hand and a revolver in the other.

The hill tribes have been fairly content to fight among themselves since 1930. In that year, however, 10,000 of them came out of the mountains to lay siege to the Pakistani city of Peshwar. Rugged hombres! (You do not wave or smile at the women in the Khyber Pass!)

Our first stop in Afghanistan revealed a great difference in the attitude of the people from what we had become accustomed to in India and Pakistan. We sat down at a little streetside restaurant or a cup of tea, and immediately three or four Afghanis at a nearby table began to argue over which one of them would pay for our tea! This proved to be pretty much typical of the Afghanis, who are a very outgoing and disarmingly friendly people.

We spent the entire next day riding slightly over 100 miles to the city of Kabul. The road follows the Kabul River, and the canyon and pass are truly spectacular. The deep blue-green of the river stands out sharply against the brown of the rugged, arid mountains. We swam, fished, photographed and just had a helluva good time.

Kabul itself is a very fascinating city, with the vivid contrasts of dusty streets and herds of sheep next to modern hotels and high-rise apartments. It is hot, windy and dusty, but the people make up for the city’s physical shortcomings. Without doubt, the greatest sight in Kabul (at least for four hungry motorcyclists) is the buffet line at the Khyber Restaurant. After a month of rice and curry, we could not believe our eyes—steak, roast beef, chicken, potatoes, gravy and fresh vegetables and fruit till the world looked level! All the food you can eat costs about 85 cents.

We stayed in Kabul for three days, one more than planned, because we simply could not leave the food. The day before we were to leave, Bill’s bike suddenly died and would not restart. The problem was quickly determined to be electrical, and a series of checks soon narrowed the trouble down to the zener diode. The diode, which acts as a voltage regulator, had shorted. Not having a replacement, we were faced with two alternatives. We could leave the diode out of the alternator circuit and run continually charging, or we could leave the diode out and add a series switch, which would allow periodic recharging of the battery with the alternator running open-circuit the remainder of the time. The problem in the second and more attractive alternative is that alternator voltage goes up as load goes down, and we were concerned that the peak open-circuit voltage might be sufficient to break down the alternator insulation and cause alternator failure.

As mentioned earlier, help usually materializes in the most unlikely manner at times such as this. This time it was in the form of a U.S. college-trained electronics man and his AC voltmeterlocated on the second floor of a little mud and straw building. With his help we determined that the open-circuit alternator voltage would be only about 50 V rms at 4000 rpm, which we considered safe. We therefore put the switch in the circuit and ran all the way to England without further trouble.

The next 500 miles promised an improvement in road conditions if nothing else. The entire east-west route through Afghanistan is a new high quality two-lane road (the asphalt section from Kabul to Kandahar was built by the U.S. and the concrete section from Kandahar to Herat by the USSR).

As we left Kabul, we started to climb almost at the city limits and continued to do so for the first 80 miles, climbing from 6500 feet to over 9000 in the process. The best gasoline available in Afghanistan is some stinking stuff from Russia of about 70 octane. Because of the upgrade for the first few miles and a headwind, we spent very little time in fourth gear. The gasoline would not allow enough throttle opening to pull fourth gear even on the level against the 40-mph headwinds. Not only would the engines not shut off due to pre-ignition, but this gasoline was so bad that a hot engine would actually start with the key off! Thanks to gentle hands on the throttle and tough Triumphs, we made it to Kandahar with all pistons still having tops.

The next day was little better. We got a very early start to avoid driving in the

heat of the day and thus minimize damage to both us and the machines. We made the 200 miles to the Farah River by noon and spent till 5 p.m. in the pool. Yes, that’s right, in the pool! In addition to building the road in this section, the Russians built several hotels for travelers along the new route. They are beautiful hotels and the one at Farah is no exception. However, it seems starkly out of place, standing alone in the middle of this rugged, high plateau, and is, in fact, seldom visited. The hotel has an ultra-modern kitchen with electric ranges, upright freezers, ice machine, automatic steam cookers and an automatic commercial dishwasher— none of which has ever been used! In fact, I doubt if electric power of the proper voltage is available to run the equipment. The menu offers rice, meat and potato dishes, all of which are prepared outdoors behind the hotel in the old-fashioned way. Having had some opportunity to observe the United States foreign aid program in action, it was comforting for me to see some Russian equipment slowly rusting away.

After a couple of days in Herat, it was on to the Iran border and the infamous cholera quarantine camp. Each year, the Iranian government sets up a program to test everyone entering from Afghanistan for cholera, and they are kept in quarantine until the results are back—usually two to three days. At the time we crossed, 2500 people had been tested over a period of three months with zero-positive results, but they continue to play the game. The camp consisted of 30 four-man tents (each with six beds), a testing tent, a beer and soda tent, a small mess hall, and about 250 people becoming slowly encrusted in the blowing sand.

While in the cholera camp I had the first flat tire of the trip—on the rear, of course. Well, if you have to have one, it might as well be when you can’t move for three days anyway.

We were released from the camp on September 4, and then entered the section of road that we had been dreading all along—the 600 miles of unimproved road from the Afghanistan frontier to the Caspian Sea. We rode the 140 miles of gravel from the border to Mashad that day and took care of our bikes in the evening (washed the drive chain and turned the automatic oiler off for the dirt ahead).

From Mashad there were 80 miles of pavement, which provided a welcome break before the real hell began. We were 30 miles onto the gravel when Spence got another flat. It was beginning to look as if we were going to pay the price in tires on this bad road, but this was the last. The road was not only unsurfaced, but was very rough with large rocks in many sections—a real bruiser. The packs we had strapped to the seats were continually shaking loose, and the cameras had to be carried slung over our shoulders to prevent their being battered. The kidney belts we had packed got their first serious use.

Two days from Mashad, we dropped down from the high, brown, arid country we had traveled since Pakistan to the lush Caspian plain with its miles of green melon fields. This was also the end of the unimproved road, and pavement never looked so good! We spent the night in the Persian resort area of Babolsar and went for a swim the next morning, letting the gentle Caspian surf wash away the desert dust of the past 2000 miles before riding over the mountains to Tehran.

We stayed three days in a campground near Tehran and tried without success to locate a replacement zener diode for Bill’s bike. The sticking throttle problem had cured itself on all the machines but mine, which was getting worse. It finally got so bad in Tehran that I had to turn the key off and on to get back to the camp from downtown. One day in Tehran with everything in perfect working order is more dangerous than three years in Vietnam, and driving with a sticking throttle is nothing short of suicidal. So, it was tear things apart again and try once more to cure it. This time I got it. After all the fooling around we had done with those four carburetors, we discovered the problem was actually in the cable length adjusting device. We fashioned a splint of wood and electrical tape that held the cable in a straight line where it passed through the adjuster and the problem was solved.

The morning of September 11 we were again on the road with the goal of covering the 390 miles to Tabriz in one day. It was so cold that we truly could not endure it, and, with the numerous tea stops, we made only slightly over half our planned distance to the town of Sandjhan. Here we bought gloves and heavy jackets and locked ourselves in the hotel room to thaw out. Between Tehran and the Turkish border the altitude is 6000 feet. However, the temperature at Sandjhan was actually not so cold (55 to 60 F), but at 60 mph, without cold weather clothing and after three years conditioning to the tropics, 55 degrees can be cold. Between Sandjhan and the next stopping point of Marand, we passed mountains with snow only 1500 to 2000 feet above the highway.

(Continued on page 87)

Continued from page 64

On September 13 we enjoyed some of the most beautiful scenery of the trip. Mountains and streams, flocks of sheep, camel caravans, fields of melons, and blue, blue sky were all part of the spectacular scene. Almost immediately after leaving the little town of Macou, just east of the Turkish border, Mt. Ararat loomed up in front of us, its sparkling white snow cap standing out sharply against the bright blue sky. The volcanic mountain is 17,000 feet high— an unforgettable sight.

The officialdom at the Turkish border was reminiscent of the Orient—complete chaos. After a couple of hours of fooling around, though, they finally got us processed—even becoming a little lighthearted toward the end. The officer, who made the final check of our bikes, wanted to see us race the 50 yards from the checkpoint to the big arched gate that led out of the courtyard. He drew a starting line on the ground, lined us up, gave a dramatic countdown, and sent us off with roaring engines and front wheels reaching for the sky, much to the delight of the crowd of tourists in the courtyard. It was really a pleasant change of pace to find an official with a sense of humor.

Mt. Ararat was again in clear view as we crossed the border, and we stopped to take more pictures. The mountain has an almost magnetic attraction about it that was hard to leave behind. We camped that night not far from the border and discovered that nights in this country can be every bit as beautiful as the days. The star shows are spectacular. The clear desert air contributes to the beauty of the nights as well as the days. We awoke in the morning to find frost on the sleeping bags. It doesn’t take long for that temperature to drop once the sun goes down.

The next couple days were filled with more great high altitude scenery, and we continued to camp out at night. There was pass after pass as the road repeatedly dropped to 3000 feet only to turn again and climb to 6000 feet plus. Winding roads, switchbacks, mountains, rivers, and picturesque villages were the order of the day. Late in the morning of September 15 we were back at sea level in the Black Sea town of Trabzon. From Trabzon we followed the Black Sea coast to the village of Unye. Near midday we met a young English couple riding a 1969 Triumph TR6R outfitted almost exactly like ours. They were on their way to Australia, backtracking the route we had just come over. After trading lies for a few minutes, we told them about what they might expect in the months and miles ahead.

We had been warned on many occasions about the rock throwing we could expect from the Turkish children, and they lived up to their reputation. Fortunately they miss most of the time, but Spence was hit a solid blow in the ribs, and a small stone hit me in the side of the helmet. Some of the rocks they throw are big enough to cause loss of control if they hit squarely.

After two days in Ankara, Turkey, we proceeded to Istanbul. We crossed the famous Strait of Bosphorus at 4:30, September 18, and were officially in Europe! We stayed on the “old” side of the Golden Horn and spent the next three days exploring this famous eastwest crossroad city. We saw the Blue Mosque and the St. Sophia Cathedral— the two finest examples of Byzantine architecture in the world. We took a leisurely ride along the Strait of Bosphorus to its outlet into the Black Sea, and made the best of three days in one of the world’s most historic cities.

Shortly before leaving Istanbul, we met two more overland motorcycle travelers—two Canadians on a TR6R and a Trophy 250, which they had bought in London and ridden 8000 miles in a month.

That afternoon there was another border to cross, this time into Bulgaria, and we had a little trouble with the “people’s” border officials. Bulgaria has ruled that no one with a beard or long hair may enter, a rule obviously aimed at the many hippie travelers. Quite obviously we were not hippies, but Bill had a beard and mustache and Spence had not shaved since Calcutta. The border police would not grant either of them permission to enter the country without shaving. We did our best to talk them out of it but to no avail. The only choice was to process back into Turkey and go 200 miles out of our way through Greece or shave. They elected to shave and did so using the cold water of their canteens and the mirrors on their motorcycles. It was some sight. I could only feel for them as they ripped through six-week growths with cold water. During the shaving process I could not resist the temptation to rib the officials; I asked the one who had given the order to shave, “Didn’t V.I. Lenin have a beard?” At first he looked properly gruff, then he broke into a smile, leaned up close, and said, “Yes, Lenin had a beard and so did Marx, Engles, and Joseph Stalin, but the Russians say we have to make everybody shave.” We all had a good laugh and from then on everyone was in a much better mood. The guard even posed for a picture as he handed over the clearance papers.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 87

On the following day, as we began our ride through Communist Bulgaria, the first noticeable difference was the ever-present propaganda posters, most of which are pointedly anti-U.S. Either a red star, a clenched fist, or a happy peasant faced us constantly. That evening we were treated to a big celebration ip the capital city of Sophia. It was a children’s holiday and everyone marched down to the central square. It is very hard to explain in print the sensation one gets at a communist rally or celebration—a chill actually does run down your spine. You definitely get the feeling that you just don’t cut class on the community happening!

While the big celebrations were in progress, we met a young fellow who subsequently invited us to spend the night at his parents’ house. Qur friend, who had best not be named, made no effort to conceal the fact that he was less than satisfied with the rewards of communism. His father had been a successful businessman with his own small factory when all private property was nationalized in 1949, and they now live at what would be far below the poverty level in the States although it is probably above average for Bulgaria. A three-room apartment was home for our friend, his parents, and his grandmother. He slept on a wooden bench in the kitchen, while we took the couch that was his usual place and three spots on the living room floor, that is, the entire living room floor. In fact, I slept stretched out under the table because of lack of room.

The following morning, as we were leaving Sophia, we passed a poster showing a Vietnamese peasant with rifle held high as an American plane fell in flames in the background. It was a colorful poster and, because we had all spent some time in Vietnam and it was of particular interest to us, we stopped to take a picture of it (our first mistake). We had no sooner stopped when the police arrived on the scene, asking to see our passports. We presented them, whereupon they were confiscated, and we were told that the three of us involved would have to follow to the station. Not being terribly impressed with this idea, we put up a minor argument (our second mistake). Before we knew what was happening, the uniformed officer was going for his gun, and a plainclothesman suddenly appeared and started doing some shoving. It became very apparent that we probably should reschedule our day to include a side trip to headquarters, so we got on the rigs and followed. Bob, who was not involved, followed some distance behind to see where they were taking us and how long we would be held. If we were not released soon, he would go to the U.S. Embassy and report our location. It was not at all impossible that we might be thrown in prison and “forgotten” for a couple years—particularly with all those Republic of Vietnam stamps in our passports—and we at least wanted our forwarding address known!

Once inside the station, they told us to sit down on a bench, and one officer disappeared with our passports while the other just hung around looking mean. I asked to make a telephone call and was very unceremoniously refused. After about a half hour, a third officer

returned with the passports and announced that we were finished, much to our relief.

We then went to report the incident at the consulate. The consul was very nice, but not too comforting when he said, “OK, just send us a card from Belgrade, Yugoslavia, so we know you got out”—as if there was some doubt about it! Sure enough, when we arrived at the border we found that we were not really finished, as we had been told back in Sophia. A note had been written in Bill’s passport, and we were told that since we had been in trouble in Sophia we would now have to pay a fine. This hardly seemed fair and we complained that we should have been told about the fine in Sophia. A half hour of translations back and forth transpired before they were convinced that we were prepared to sit them out rather than pay, and they gave up. However, we were told that next time we come to Bulgaria, we will have to behave. The next time may be a while in the future as none of us had any great burning desire to return to Bulgaria.

Yugoslavia, while it is nominally a communist country, was as different from Bulgaria as black is from white; this was obvious as soon as we crossed the line. The border officials were friendly and got a big chuckle out of our problems in Bulgaria. They seemed to enjoy making fun of their hard-line cousins to the East.

The first night in Yugoslavia was spent at a campground about 35 miles east of Belgrade. During the night someone entered the compound and robbed Bill of $180 in cash, $260 worth of travelers’ checks and all his clothes. The thief was at least considerate in that he searched through the case for what he wanted and threw it back over the fence with all the important papers (passport, carnet and insurance papers) untouched. The loss of those papers would have stopped us dead. A Swiss motorcyclist sleeping a few feet from us was similarly victimized. After repeated calls, the police finally came. They took a cursory look around and eventually took a report, but really didn’t get too concerned. We learned later that campground theft is not uncommon in Yugoslavia, and caution should be practiced by tourists in that country.

The investigation and the filing of reports took the entire day, and we arrived in Belgrade at dusk. One more day’s riding through farm country brought us into Austria. We were finally in the freedom of “Green Card” (a proof of insurance form which must be shown to take a vehicle across a border in Western Europe—eliminating the carnet routine.) Western Europe and from here on life would be comparatively easy.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 89

We rode through Graz and on to Salzburg, passing through some of the famous ski and lake country enroute. Austria is just as pretty as all those travel posters. Blue lakes nestle among towering mountains; cozy little villages, lush green pastures, and fields of flowers abound. Good, smooth roads winding through all this make it great motorcycle country.

September 28 was spent locating ski areas near Bad Ischl and St. Gilgen and watching a cross-country motorcycle race near Salzburg. The races were great sport with riders from four or five countries competing, but the only spills we saw all day were our own. Both Bob and I piled up on the way to the race—too much of the spirit I guess.

Late in the day we rolled into Salzburg and grabbed the autobahn for Munich. This being our first experience with German autobahns, we were hanging on tight for those 100 miles. You turn the wick up to 80 mph and think you are doing fine only to find a big Mercedes passing you on each side and another, 10 feet behind, flashing his lights for you to clear the way! They do fly! It was cold and we really did not care to go quite so fast, but there is no choice on a German autobahn.

The arrival in Munich was a minor triumph. At the outset of the trip, one of our goals was to make it to Munich in time for the Oktoberfest, and we had estimated our travel time from Calcutta to Munich at 60 days. We made it in 58. I guess that proves we were good planners—or damn lucky.

After finding a place to stretch out for the night at a local campground, we headed for the main attraction, the world famous beer bust known as the Oktoberfest. Lights from the many rides and food booths can be seen for blocks, and as you approach the gates and note that 50 percent of the people you are meeting are hopelessly drunk, you realize that the stories about the beer halls were not exaggerations.

Each of the beer halls, of which there are seven or eight, is run by a competing German beer company. Each holds close to 3000 people and all are completely packed to standing room only. In the center of each huge hall is an elevated stage with a Bavarian “um-pa-pa” band playing German drinking songs. Liter beer mugs are raised overhead as large groups of people sway back and forth and sing along with the music. The entire family from grandma to preschooler is there. It is, in fact, the world’s largest beer bust, and not a few of the participants overdo their merrymaking. As our cab driver dropped us off at the campground and pointed us toward the gate, there could be little doubt that we were among those who overdid it! It took till noon the following day to partially recover. When we went back the next night, it was strictly as spectators.

From Munich we rode north to the U.S. Army base at Bamberg where I located an old school friend with whom we stayed for three days. It is amazing how much one can appreciate a warm apartment and a hot shower after a couple weeks of freezing and sleeping on the ground. Definitely one of the fringe benefits of a long-range, lowbudget motorcycle trip is a new appreciation of simple pleasures—like a bed or a shower!

We continued north from Bamberg toward Amsterdam with the intention of taking the Rhine River route where possible. We promptly got separated, made the trip in two groups, and met two days later in Amsterdam where we spent a couple pleasant days sight-seeing before setting out for the final destination—England. One day’s hard riding took us from Holland through Belgium, across a corner of France, across the channel to England and on to London. Four countries in one day!

On October 13 we set out on the final 150-mile leg of our 10,000-mile journey to the Triumph factory at Coventry and a homecoming for our four red TR6s. We called the factory the following morning, talked to John Wilding, Triumph’s very personable export sales manager, and informed him of our journey and safe arrival in Coventry. He promptly came to meet us on a new Trident and escorted us to the factory, where we were photographed, interviewed, questioned by the maintenance department, treated to lunch, and generally given a very warm reception. The maintenance people, whose lives are spent listening to bitching, were very pleased to hear that the trip had been almost trouble free. In fact the sum total of our troubles was: two flat tires, three leaking main bearing seals, three leaking pushrod tube gaskets (exhaust) and one shorted zener diode. The one problem that prevented us from traveling was the diode and that for only part of one day.

During our week in Coventry, we had the machines put back in like-new condition at a local repair shop before having them crated at the factory for shipment home. It had been one helluva trip, covering 10,000 miles and 17 countries, and we all found it very hard to park the bikes and walk away. Spence summed up the feeling by saying, “I feel just like I’m having to shoot my old horse.” However, boxing the rig up is not quite that final, and we all knew we would see them again someday. In fact, as we walked out of the factory gates to catch a bus, someone said, “Hey, you guys want to ride to Alaska next summer?”

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ASIMILAR TRIP

DO invest in a Barbour suit or similar riding clothing even if the trip is to be made in warm weather. We didn’t and suffered through weeks of rain in blue jeans and overall jackets.

DO buy good quality panniers and luggage carrying equipment because the bumping and vibration (not to mention spills) of a long trip really play havoc with them. We had very good luck with the Craven Golden Arrow set and would recommend it.

DO use a windshield. Long days in the saddle are shorter with one.

DO wear a helmet and get a sun visor for it. I would not recommend a face shield, as we each had one or more of various manufacture and within a week all were too scratched to be used. We cut them off just above eye level and covered them with black tape for use as visors.

DO take the time to determine the fuels available along your route and choose the compression ratio for your machine accordingly. We got by with our 9:1 ratio on some very bad fuel, but we would have been more comfortable and safer if we had ordered the bikes fitted with the optional 7:1 pistons.

DO include pills for dysentery in your medical supplies. If you eat the local food, which is part of the fun, you will get it!

DO NOT load yourself down with too many spare parts. You will find that everything but a real specialty item can be found or fabricated. One set of pistons with rings and a set of valves might be included along with the obvious points, plugs, gasket material, patch kit, etc.

DO NOT carry movie gear unless the primary purpose of the trip is to take pictures. You will find, as I did, that nearly all good movie scenes are staged and that takes time—a lot of it. Also keep in mind that any camera carried anywhere on a bike will be damaged and possibly ruined. Screws vibrate loose, dust works its way into every corner—it is just generally very rough on camera gear. However, I feel it is worth the sacrifice of a still camera to get those once-in-a-lifetime pictures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumIllinois Success Story

JUNE 1970 By Lee Strobel -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

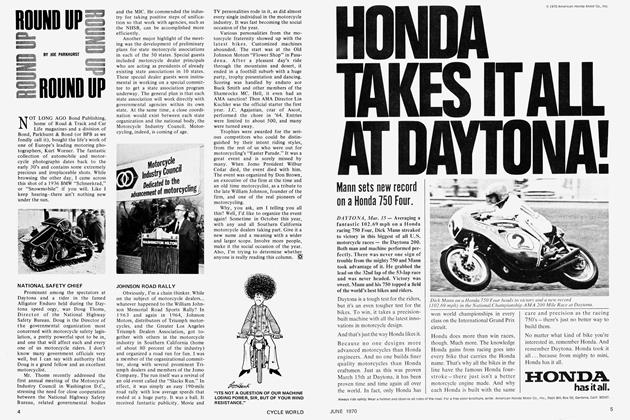

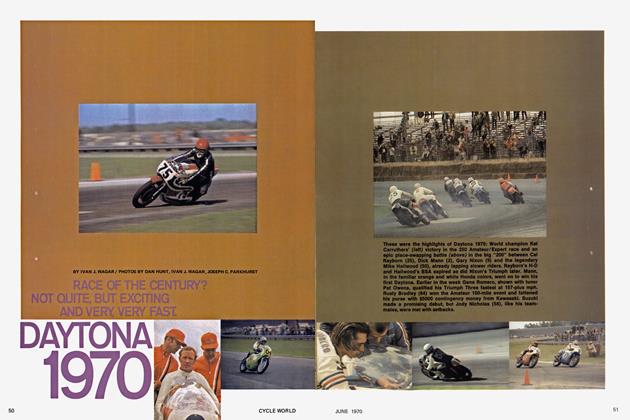

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureDaytona 1970

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Competition

CompetitionThe Mint 400, '70 Style

JUNE 1970 By Bryon Farnsworth